19/019

Anastasia Elrouss

Architectural Practice

Beirut

«Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place.»

«Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place.»

«Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place.»

«Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place.»

«Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio...

I have been actively working in the architecture field for nearly 15 years. I graduated in architecture from the American University of Beirut, which I attended from 2000 to 2005, and where I currently teach design courses. At first, I worked in Beirut at Samir Khairallah & Partners (2005-2006) and at Jean Nouvel in Paris (2007). In 2008, I became the head of YTAA and soon after a founding partner and general manager of the architecture firm (2011-2017).

In November 2017, upon exiting YTAA, I founded my own architectural practice ANA-Anastasia Elrouss Architects. At my new firm, I continue to uphold my main design philosophy: that architectural and urban thinking can never be stagnant. For me, architecture is about exploring options and about opening a dialogue, while encouraging an ongoing conversation.

With active projects in Lebanon, France, Romania, Canada and Dubai, and others planned further afield, I became a constant traveler both for my architectural work and for my global speaking engagements. In 2014, and in collaboration with MEXTROPOLI, I worked on redefining the meaning of public space in Mexico City through the use of informal markets.

Most recently, a number of my projects received various international nominations and awards. The Haddad Compound in Canada was nominated for theGerman Design Awards 2019 in thecategory of Architecture, and the DAM-MAD villa in Beirut won theGerman Design Awards 2019 with aspecial mention in the category of Architecture. The DAM-MAD villa also won theIconic Award 2018: Innovative Architecture – Best of Best in the category CONCEPT with distinction. (Image of the DAM-MAD villa attached above)

I have also been giving speaking engagements at international architectural and urban conferences and symposiums, including Milan (May 2016 for Archmarathon), Montréal (September 2016 at Université de Montréal) and Bucharest (October 2016 at Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism). In 2017, I returned to Bordeaux, where I spoke about my role in the city’s Quartier Brazza development, and in February I was once again part of Agora, this time as a jury member for the Biennale’s Appel à Idées prize. Most recently, in 2018, I spoke about my architectural vision and the importance of gender equality in the workplace at many local and international universities.

I am a passionate architect and a firm advocate for women, this is why in 2017, in parallel to my architectural practice, I founded Warchée, a Lebanese NGO advocating for international social and gender equality in the workplace, both in Lebanon and abroad.

“We live in a world that is changing faster than ever. In recent years, architecture has evolved at an increasing speed, but today it feels that we are on the verge of a revolution. The time has come to impose and experiment, to push toward a new design framework. Architecture allows us to give shape to our dreams and interpret them in reality.”

About ANA-Anastasia Elrouss Architects

My architectural office ‘ANA-Anastasia Elrouss Architects’ is an architectural and urban practice founded in 2018 that’s passionate about the built and the unbuilt environments. My architectural vision aim is to reimagine how the user connects with the world in which he or she lives.

Launched and based in Beirut, my architectural firm works with a team of international consultants who understand its ethos: creating a structured intervention that results in spaces of liberty, allowing appropriation and leaving room for appropriation. In my architectural work, I usually focus on the concept of the transient – this fourth dimension that is sometimes overlooked by architects. With its designs, my firm seeks to create “evolutive” or “volume capable” buildings that adapt both to the user’s needs and to the environment in which they exist.

While I am a strong believer in spatial fluidity, my work places a strong emphasis on details and transitory objects. Whether designing a city, a building or a house, the same rules apply – albeit on a different scale. my work is identified by its accessibility and flexibility, allowing the user to have a say in the space being created.

While always keeping the end user in mind, I like to also reflect the moment, the temporality of the way we live. My work captures the moment, while rethinking the preconceived limits of human space. The architecture I design and draw is engaged in multi-level conversations with itself, the client and the user, in order to create flexible, livable and highly distinctive buildings, villas, structures and public spaces. Once I complete the work on a specific site, the project must be still able to evolve according to the end user’s needs and life changing events. And when working within existing buildings, I tend to show how each place can be inhabited differently, allowing a whole new building – and lifestyle – to emerge.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

The notions of flexibility, interpretation and evolution are part of my vision for an optimum living space. I’m also interested in secret and intimate spaces, such as secret gardens and/or volumes physically connected to other functions within the same project. My aim is to give the user freedom to make the space public or private, depending on their needs.

This last point reflects the way I lived my youth. I lived freely in an open and limitless house (without interior doors) shared by six women from several generations. During my childhood, I created my own secret spaces, both real and imaginary. This way of perceiving space extended beyond my house and spread all around when I walked in the historical center of my home city Tripoli, located in Northern Lebanon.

I developed an escape mechanism that helped me when I was conceiving my projects, both in my architecture studies and in my professional life. Drawing the ideal situation that would capture the tastes and needs of my clients became a natural exercise where all the definition of spaces exploded. In my approach, I highlight the role of people living in a specific place (home and city) and then I create a continuous dialogue between public and private. Ultimately, I build secret places that open up an imaginary world for the inhabitant, without limits or judgment.

How did your professional experience as an architect help you become an activist for gender equality in the construction field and in architecture specifically?

Travels, Meetings and a Desire to Change the World

I’ve known since I was a child that change would never happen on its own. My dream was to make a positive change as a woman architect and urban planner. Anastasia Elrouss Architects and Warchée NGO came about as a result of women meeting and seeking to effect change – women whose paths most probably would never have crossed if they hadn’t been engaged in the same profession.

Through my professional encounters across the globe, through a real exchange of cultural values and as a Lebanese and female architect and urban planner, I felt the need to launch a debate about gender equality and the role of women in the workplace and the world. This came about as a result of similar challenges that working women have to face even when they’ve had different career paths and lived in different countries.

At the same time, I felt that I was shining a new light on this topic through my life experiences as a Middle Eastern female architect and urban planner, and also through my professional engagements in such differing places as France, Holland, Romania, Dubai, Canada, Mexico and Lebanon. It was clear that women still had a long road ahead to achieve gender equality, and that their skills and achievements wouldn’t be enough to ensure real independence.

I realized that the fight for gender equality in the workplace, in various cultures and countries, was just beginning, and that we’d have to work at every level – professional, legal, cultural, geographic and educational – to further women’s rights. If a woman’s achievements remain limited to her person alone, it will be impossible to effect change. Real gender equality can only succeed once each and every working woman has been successfully integrated into the workplace and on an equal footing.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project?

I always wanted to work on the transformation of spatial realities through architecture, utilizing architecture to tap into experience, senses and emotions. So, I chose to work on Lebanon’s juvenile boys prison “Islahiyet Elfanar,” a poorly designed space that didn’t produce any psychological improvement for the young incarcerated boys and didn’t allow them to reintegrate into society once they exited the prison.

The prison consisted of bedrooms, a TV, two computers, a kitchen and a playground. I took the position of empowering the users in their internal spaces through revisiting the programmatic experience and introducing self-healing activities through which they can learn a craft or trigger a passion to help them dream, have future goals and get reintegrated in society. My designs included an acting school; a painting and pottery school with a large exhibition space; wood, metal, glass and pottery workshops (and the possibility to sell their produced items from the prison on open days); a computer school, with regular visiting professors, where the juveniles are mixed with school students through educative program; and multifunctional mini basketball and mini football fields. Considering that the juvenile prison had to be very safe for inhabitants and visitors, the spatial layering reflected this issue via a continuous process of unfolding hidden spaces with many controlled gates. For example, the theater could be completely disconnected from the rest of the prison when it was accessed by the public, and then reintegrated again through large mobile trucks. The inspiration started with old fortresses but in a contemporary manner, in which physical and spatial mobility could make them flexible and accessible while they remained monumental and imposing.

For two years, I was directly in contact with the 30 boys in prison, and I conducted weekly workshops with them on drawings, sports, computers, crafts and theater because I wanted them to be my main clients and rebuild the prison with them in mind. The interesting part is that I learned the secret activities and how they appropriated empty spaces while injecting them with their dreams. So, a hidden circulation layer was added in between all activities and left empty as a space of liberty in which they were free to express their anger, their hopes and their talents. The in-between space was a breath of fresh air because it was conceived with an internal 70m vertical urban farm, open to the sky by large skylights, and functioning as an internal greenhouse completed with a suspended garden. The internal spaces of the juvenile prison were made of flexible and transformable materials, while the exterior remained a layering of concrete walls, giving a blank, harsh impression from outside but warm and inviting on the inside.

My main advisor for my thesis project was Howayda Elharithy, who was instrumental in pushing the users themselves to recreate their internal spaces in order to add life and human traces to the juvenile prison. She also pushed me experiment with how the inserted activities can create income and value to the prison and to people living outside of it. Through my architectural studies, I was also positively influenced by my professor Marwan Ghandour, who encouraged me to always take a clear architectural and urban position and to push my experimentations to either highlight a reality or try to transform it and appropriate it through the production of space. I learned from Marwan that a neutral architect cannot push any boundary, and that it is waste of time, budget and effort if change doesn’t happen through architecture.

These two professors influence my current work because I believe in rebellious architecture, I work on the five senses through layering of materials and functions, on the surprise effects in spatial experiences and on recreating a space that represent the user deeply through always shaking the grounds of traditional expressions. For me architecture is a living being that can transform, adapt and certainly be an important player on lives through small houses, through building and through cities.

What are your experiences founding Anastasia Elrouss Architects and working as a self-employed architect?

As a woman architect, the first step was a bit complex because I always dreamed to leave my physical trace through architecture, but I also wanted to be an active change-maker architect, working on gender equity in the workplace and in the construction fields. I first made an important international impact as a founding partner in a Beirut-based architectural firm, but to truly make my mark as an architect and as a woman, I realized that I had to venture out on my own. So, believing firmly that through my architectural vision I could change the world, I founded my own firm, alongside an NGO, Warchée, which works on the gender-equity subject. The challenge was very big because I was perceived as very demanding, too ambitious and too young in a Mediterranean social context in which women are supposed to be primarily thinking of their social status with respect to their family first.

Founding my own firm was a very enriching experience for me because it allowed me to get in touch with my architectural skills in a more private and direct manner. It gave me the freedom to express and impose my architectural visions in several ways:

- Highlighting the users (the human) and drawing the spaces of their dreams through reinterpreting reality (using emotions, spatial layering and experience).

- Working with the immediate (the site) and the larger context (the city or neighborhood) while injecting a rebellious act of either continuity or disruptiveness to create a powerful relationship with the context.

- Creating intricate spatial experiences through physical and emotional spatial layering and reinterpreting the physicality of any given programmatic function.

- Researching innovative materials and construction techniques that are custom-designed for every project and client in order to write a different story each time through architecture.

I find that the experience of a self-employed architect is thrilling. It’s a daily challenge to work on oneself first and to build a team of talented architects around you. I believe in team exchange and research while respecting common values: creativity, experimentation and reinterpretation with a sense of humility. In my work as an architect, I reinterpret time and space. I give them a great fluidity by trying to subtract the inner limits between functions. I redefine the reality of these functions through their utilities. I think about how to inhabit the space specific to each person. I gradually redefine the nature of the boundaries between the inside and the outside and make them devoid of any gender identity. What previously was originally built by men is part of a new structure that’s become more fluid and sometimes more feminine.

How would you characterize Beirut as location for practicing architecture? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

Beirut’s skylines and landlines are very interesting to live and to work with especially in the architectural and urban planning fields. For me Beirut is a chaotic city but the chaos is ordered by individuals who dare to appropriate the in between and the voids within the city. This inspires me to experiment more with the spaces of appropriation, transformation and secret getaways, while redefining the limits of my architectural interventions.

The disadvantage of the system is that there is no general urban planning common vision, so contemporary architectural projects end up being the initiative of private clients who are willing to take the risk and bring new spatial ideas up front. These private initiatives usually are very adventurous and seek to create a landmark.

The city of Beirut and Lebanon as a whole are an important role player in the projects I create because they are multilayered with a never-ending experience between extremes.

About ANA-Anastasia Elrouss Architects

My architectural office ‘ANA-Anastasia Elrouss Architects’ is an architectural and urban practice founded in 2018 that’s passionate about the built and the unbuilt environments. My architectural vision aim is to reimagine how the user connects with the world in which he or she lives.

Launched and based in Beirut, my architectural firm works with a team of international consultants who understand its ethos: creating a structured intervention that results in spaces of liberty, allowing appropriation and leaving room for appropriation. In my architectural work, I usually focus on the concept of the transient – this fourth dimension that is sometimes overlooked by architects. With its designs, my firm seeks to create “evolutive” or “volume capable” buildings that adapt both to the user’s needs and to the environment in which they exist.

While I am a strong believer in spatial fluidity, my work places a strong emphasis on details and transitory objects. Whether designing a city, a building or a house, the same rules apply – albeit on a different scale. my work is identified by its accessibility and flexibility, allowing the user to have a say in the space being created.

While always keeping the end user in mind, I like to also reflect the moment, the temporality of the way we live. My work captures the moment, while rethinking the preconceived limits of human space. The architecture I design and draw is engaged in multi-level conversations with itself, the client and the user, in order to create flexible, livable and highly distinctive buildings, villas, structures and public spaces. Once I complete the work on a specific site, the project must be still able to evolve according to the end user’s needs and life changing events. And when working within existing buildings, I tend to show how each place can be inhabited differently, allowing a whole new building – and lifestyle – to emerge.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

The notions of flexibility, interpretation and evolution are part of my vision for an optimum living space. I’m also interested in secret and intimate spaces, such as secret gardens and/or volumes physically connected to other functions within the same project. My aim is to give the user freedom to make the space public or private, depending on their needs.

This last point reflects the way I lived my youth. I lived freely in an open and limitless house (without interior doors) shared by six women from several generations. During my childhood, I created my own secret spaces, both real and imaginary. This way of perceiving space extended beyond my house and spread all around when I walked in the historical center of my home city Tripoli, located in Northern Lebanon.

I developed an escape mechanism that helped me when I was conceiving my projects, both in my architecture studies and in my professional life. Drawing the ideal situation that would capture the tastes and needs of my clients became a natural exercise where all the definition of spaces exploded. In my approach, I highlight the role of people living in a specific place (home and city) and then I create a continuous dialogue between public and private. Ultimately, I build secret places that open up an imaginary world for the inhabitant, without limits or judgment.

How did your professional experience as an architect help you become an activist for gender equality in the construction field and in architecture specifically?

Travels, Meetings and a Desire to Change the World

I’ve known since I was a child that change would never happen on its own. My dream was to make a positive change as a woman architect and urban planner. Anastasia Elrouss Architects and Warchée NGO came about as a result of women meeting and seeking to effect change – women whose paths most probably would never have crossed if they hadn’t been engaged in the same profession.

Through my professional encounters across the globe, through a real exchange of cultural values and as a Lebanese and female architect and urban planner, I felt the need to launch a debate about gender equality and the role of women in the workplace and the world. This came about as a result of similar challenges that working women have to face even when they’ve had different career paths and lived in different countries.

At the same time, I felt that I was shining a new light on this topic through my life experiences as a Middle Eastern female architect and urban planner, and also through my professional engagements in such differing places as France, Holland, Romania, Dubai, Canada, Mexico and Lebanon. It was clear that women still had a long road ahead to achieve gender equality, and that their skills and achievements wouldn’t be enough to ensure real independence.

I realized that the fight for gender equality in the workplace, in various cultures and countries, was just beginning, and that we’d have to work at every level – professional, legal, cultural, geographic and educational – to further women’s rights. If a woman’s achievements remain limited to her person alone, it will be impossible to effect change. Real gender equality can only succeed once each and every working woman has been successfully integrated into the workplace and on an equal footing.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project?

I always wanted to work on the transformation of spatial realities through architecture, utilizing architecture to tap into experience, senses and emotions. So, I chose to work on Lebanon’s juvenile boys prison “Islahiyet Elfanar,” a poorly designed space that didn’t produce any psychological improvement for the young incarcerated boys and didn’t allow them to reintegrate into society once they exited the prison.

The prison consisted of bedrooms, a TV, two computers, a kitchen and a playground. I took the position of empowering the users in their internal spaces through revisiting the programmatic experience and introducing self-healing activities through which they can learn a craft or trigger a passion to help them dream, have future goals and get reintegrated in society. My designs included an acting school; a painting and pottery school with a large exhibition space; wood, metal, glass and pottery workshops (and the possibility to sell their produced items from the prison on open days); a computer school, with regular visiting professors, where the juveniles are mixed with school students through educative program; and multifunctional mini basketball and mini football fields. Considering that the juvenile prison had to be very safe for inhabitants and visitors, the spatial layering reflected this issue via a continuous process of unfolding hidden spaces with many controlled gates. For example, the theater could be completely disconnected from the rest of the prison when it was accessed by the public, and then reintegrated again through large mobile trucks. The inspiration started with old fortresses but in a contemporary manner, in which physical and spatial mobility could make them flexible and accessible while they remained monumental and imposing.

For two years, I was directly in contact with the 30 boys in prison, and I conducted weekly workshops with them on drawings, sports, computers, crafts and theater because I wanted them to be my main clients and rebuild the prison with them in mind. The interesting part is that I learned the secret activities and how they appropriated empty spaces while injecting them with their dreams. So, a hidden circulation layer was added in between all activities and left empty as a space of liberty in which they were free to express their anger, their hopes and their talents. The in-between space was a breath of fresh air because it was conceived with an internal 70m vertical urban farm, open to the sky by large skylights, and functioning as an internal greenhouse completed with a suspended garden. The internal spaces of the juvenile prison were made of flexible and transformable materials, while the exterior remained a layering of concrete walls, giving a blank, harsh impression from outside but warm and inviting on the inside.

My main advisor for my thesis project was Howayda Elharithy, who was instrumental in pushing the users themselves to recreate their internal spaces in order to add life and human traces to the juvenile prison. She also pushed me experiment with how the inserted activities can create income and value to the prison and to people living outside of it. Through my architectural studies, I was also positively influenced by my professor Marwan Ghandour, who encouraged me to always take a clear architectural and urban position and to push my experimentations to either highlight a reality or try to transform it and appropriate it through the production of space. I learned from Marwan that a neutral architect cannot push any boundary, and that it is waste of time, budget and effort if change doesn’t happen through architecture.

These two professors influence my current work because I believe in rebellious architecture, I work on the five senses through layering of materials and functions, on the surprise effects in spatial experiences and on recreating a space that represent the user deeply through always shaking the grounds of traditional expressions. For me architecture is a living being that can transform, adapt and certainly be an important player on lives through small houses, through building and through cities.

What are your experiences founding Anastasia Elrouss Architects and working as a self-employed architect?

As a woman architect, the first step was a bit complex because I always dreamed to leave my physical trace through architecture, but I also wanted to be an active change-maker architect, working on gender equity in the workplace and in the construction fields. I first made an important international impact as a founding partner in a Beirut-based architectural firm, but to truly make my mark as an architect and as a woman, I realized that I had to venture out on my own. So, believing firmly that through my architectural vision I could change the world, I founded my own firm, alongside an NGO, Warchée, which works on the gender-equity subject. The challenge was very big because I was perceived as very demanding, too ambitious and too young in a Mediterranean social context in which women are supposed to be primarily thinking of their social status with respect to their family first.

Founding my own firm was a very enriching experience for me because it allowed me to get in touch with my architectural skills in a more private and direct manner. It gave me the freedom to express and impose my architectural visions in several ways:

Highlighting the users (the human) and drawing the spaces of their dreams through reinterpreting reality (using emotions, spatial layering and experience).

Working with the immediate (the site) and the larger context (the city or neighborhood) while injecting a rebellious act of either continuity or disruptiveness to create a powerful relationship with the context.

Creating intricate spatial experiences through physical and emotional spatial layering and reinterpreting the physicality of any given programmatic function.

Researching innovative materials and construction techniques that are custom-designed for every project and client in order to write a different story each time through architecture.

I find that the experience of a self-employed architect is thrilling. It’s a daily challenge to work on oneself first and to build a team of talented architects around you. I believe in team exchange and research while respecting common values: creativity, experimentation and reinterpretation with a sense of humility. In my work as an architect, I reinterpret time and space. I give them a great fluidity by trying to subtract the inner limits between functions. I redefine the reality of these functions through their utilities. I think about how to inhabit the space specific to each person. I gradually redefine the nature of the boundaries between the inside and the outside and make them devoid of any gender identity. What previously was originally built by men is part of a new structure that’s become more fluid and sometimes more feminine.

How would you characterize Beirut as location for practicing architecture? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

Beirut’s skylines and landlines are very interesting to live and to work with especially in the architectural and urban planning fields. For me Beirut is a chaotic city but the chaos is ordered by individuals who dare to appropriate the in between and the voids within the city. This inspires me to experiment more with the spaces of appropriation, transformation and secret getaways, while redefining the limits of my architectural interventions.

The disadvantage of the system is that there is no general urban planning common vision, so contemporary architectural projects end up being the initiative of private clients who are willing to take the risk and bring new spatial ideas up front. These private initiatives usually are very adventurous and seek to create a landmark.

The city of Beirut and Lebanon as a whole are an important role player in the projects I create because they are multilayered with a never-ending experience between extremes.

Image of MM Residential Building Proposal with a skyline of Beirut behind it

Image of MM Residential Building Proposal with a skyline of Beirut behind it

What does your desk/working space look like?

The office is located in an old traditional Lebanese house in Gemmayze, one of Beirut’s oldest and most visually pleasing neighborhoods. It has 5m-high ceilings with green plants inside and on the balconies. My desk faces the plants, the sunlight and opens directly onto a high structure with three arcades. The desk is full of models and sketches, which are an important part of the design process I like to use, from the design phase through the end of the project. Reference images and perspectives hang on the walls as well in order to depict the materiality and vibes of each project.

Two main open spaces form the office, a working space and a meeting space. Both spaces house models, samples of materials and sketches in order to feel the projects at all times. The office is more of a creative atelier, with flexible seating depending on the project phase, which is allowed by the open plan. I wanted to work in a historic, traditional Lebanese house and to transform it through contemporary use. I have minimal office furniture, an internal garden and a lot of model making. The old house has become an occupied flexible volume that can accommodate a very large meeting and workshop areas. At the same time, the house can transform into very intimate working spaces for the creative process.

I like the fact that the clients and the consultants we work with experience the idea that Anastasia Elrouss Architects crafts their projects, so the process and the tools of production are very much part of the space and part of the active meetings.

From the beginning of our practice, we tried to work in different scales and programs, rather than specializing in specific fields. Parallel to that, we were lucky to receive the commission to design a single-family house in Stralsund, in northern Germany, which gave us the opportunity to realize our first building. The project kept accompanying us throughout the last 3 years and is scheduled to be completed in early 2019.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

Architecture is a way of living for me, it is a celebration of life in all its elements and it is a tool to play and recreate the essences of life, human exchange and dialogue while pushing the evolution of the status quo. Architecture should focus on a person’s dreams and impact him/her into active inhabitants, in control of their production of space under a main vision.

Architecture is a tool to tell a story in a specific way. This story can change and transform through time, function or place. The story becomes ever-changing through the variations of seasons, inhabitants, visitors, materiality and context. Since architecture is a physical statement of an idea, it’s an important tool to leave a trace in the present and for future generations. It allows clients to leave a physical legacy in this world. I enjoy telling my story through the story of my clients and combining my architectural vision with their dreams and desires.

Architecture allows me to experience all five senses, and through other people’s live, you can create a new reality, a new house, a new building, a new city. It’s very important to have an experimental reality to always remind us of the dream in which a person can act, feel and live in liberty.

Architecture is a possibility to write the future using the past and the present. It allows me to leave a trace of our era through technological, structural, electro-mechanical, contextual and geographical techniques, resulting in the contemporary architecture with which I experiment. It opens your mind to asking questions by linking generations of concepts and techniques and transforming systems for custom-made architecture on small, intermediate and large scale interventions.

We live in a world that is changing faster than ever. In recent years, architecture has evolved at an increasing speed, but today it feels that we are on the verge of a revolution. The time has come to impose and experiment, to push toward a new design framework. Architecture allows us to give shape to our dreams and interpret them in reality.

Your master of architecture?

A Book:

“The Production of Space” by Henri Lefebvre.

A Person:

Lina Bo Bardi, a Brazilian modernist architect who devoted her working life to promoting the social and cultural potential of architecture and design.

A Building:

Chichu Art Museum by Tadao Ando

La Maison Lemoine by Rem Koolhaas

How do you communicate / present architecture?

I like to communicate and present my architecture through its natural process, with models, diagrams, drawings, images and sometimes videos. Architecture is a series of layers that are experienced through tools allowing a continuous evolution of the design process. (images of the Haddad Compound tools of representation attached below)

Mood images or perspectives

The images illustrate the power of the final design concept, giving a full conceptual vision for the project. The treatment of the images I tend to produce always leaves room for the imagination, infusing a dreamy feeling into them. I prefer to have images that leave room for interpretation under a specific powerful idea, which in its depth remains a fixed guideline until the final details of construction. Light, shades and shadows are important aspects of the spatial mood and experience. The last layer is materiality, which plays an important part in impacting the senses of the user.

Diagrams and Models

During the process of concept design evolution and technical coordination, a multitude of models are always developed to test the integration of any project within its context and the main aspects that differentiate the uniqueness of the main concept. In addition, diagrammatic sections are used to test the hierarchy between internal and external spaces in relationship to the intimacy of the inhabitant. Since all the projects are custom-made structures, the models allow a clear vision of the power between structural techniques and architectural expression, where the architecture and the landscape appropriate the structure to become one entity. The proportion of all volumes are very important as well, in terms of the human scale and the territory scale, so models from 1:100 to 1:50 are developed to test the greater impact of the interventions.

Drawings

Every type of drawing illustrates one face of the project, and all together they form a multifaceted structure that is in conversation with the surroundings, the inhabitant and the environment. Sections illustrate the power of the public and private contexts, altering the spatial hierarchy into some customized ways of living. Plans express the fluidity of the experience and the possibilities to sometimes transform open spaces into having many programmatic utilities, while at other times keeping the intimate spaces drawn to the minute details. Between sections and plans, I try to work on extremes with respect to their context: fluid public spaces linked to each other mostly embedded in nature and private intimate cocoons with secret activities suspended over the horizon and the immediate context.

What has to change in the architecture Industry? How do you imagine the future?

In my opinion architecture, urban planning and private and public definition should be more experimental toward empowering their inhabitants under the umbrella of a common vision. This vision should not be static but designed and drawn to accept the changes and the rapid evolutions of our era.

I do not wish to define architecture as an industry because it omits human scale and dream layering. Architecture is a book of our lifestyles, our connections and differences, and a depiction of our social transformations through spatial hierarchy. What should be changing in architecture is the lack of sensitivity toward the context and the inhabitants because constructions are erected for the time being for commercial usages, increasing the real estate values around them without active social thinking about the long-term implications of this rapid construction process on our future cities.

In my opinion if the human scale, the emotions, needs and experiences are forgotten in the architectural process, it becomes a simple commercial commodity with no soul and no essence, and it will decay very rapidly, which is what we are seeing now in the world with buildings and cities left deserted by their inhabitants because of changing demographics that weren’t taken into consideration when the preliminary design of these structures took place.

I dream of future spaces where gender differences are no longer determining spatial boundaries, where cities are invaded by forests, internal and external colorful gardens blurring the limits between the constructed and the natural in a very iconic way without erasing the power of expression of the human touch and trace. I dream of architecture that empowers the human without erasing their essence. I imagine a future with more public space and less aesthetic treatments. Experiencing geographical wonders is very important, with the right of access to water, sea, mountains, forests and more. I imagine vertical green cities with vertical multilayered programs and circulation systems, while allowing the ground level to transform into natural forests and green parks.

Project

Haven House

Lebanon

2019

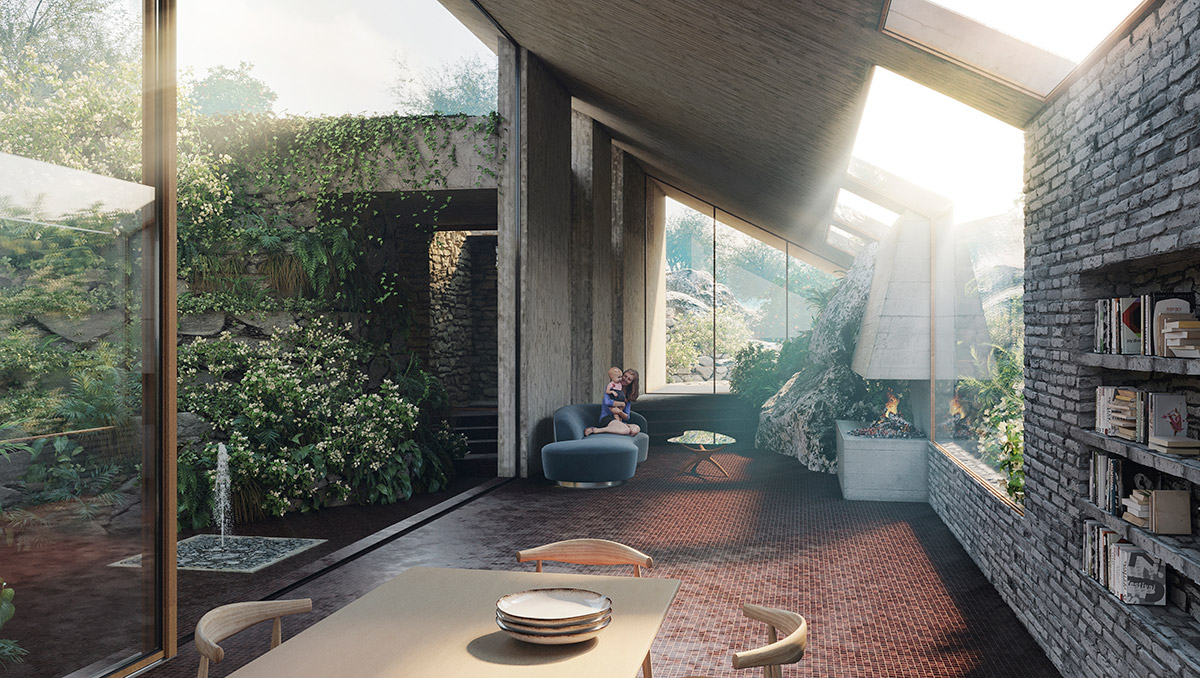

A Getaway in the Rocks

The Haven House is inspired by old Lebanese churches and hideaways that were carved inside Rocky Mountains historically and were appropriated with time by their surrounding natural environment, these small grottos remained hidden for centuries enabling their users to live their cultures and beliefs as they saw fit without any external social pressures.

The challenge was to create a hidden house with surreptitious experiences in continuous dialogue with nature at several scales and levels. These secret experiences would allow the creation of an imaginary world for its inhabitants, blurring the limits between public and private without physical boundaries or judgement.

Carved out in the rocky mountain and hidden between rocks and trees, a sloped cantilevered roof shelters the main reception space. The roof acts as continuation of the mountain’s slope and disappears in its context. The sloped roof is cantilevered from one side above the internal stepped courtyards.

Three women will occupy the house transforming the space into a spiritual retreat.

Three main planted courtyards act as natural breathing spaces for the main reception areas. These courtyards are formed by rocked boundaries from outside and are elevated to connect to the upper main garden that provides visibility on the nearby village, but remains hidden to the village through the protection of the sloped wooden roof.

The house creates an intense experience for the five senses in a short sequence of moments. From the existing olive trees distributed chaotically across the rocks, that connect to form a stone shelter for the house, to the combination of wood and fair faced white artisanal concrete used in the interior, create a stone masculine fortress on the outside and a feminine, spiritual and soft space from the inside.

The reception area takes the length of a 23 meters’ procession of experiences always in contact with the sky or with the three courtyards. Three hidden doors lead the way to the three secret sleeping spaces. A large chimney for heating and cooking, a bow window, an open Kitchen and a library are always in contact with internalized rocky walls penetrating the main space from outside.

Three bedrooms disappear completely underground with each having two carved-in, secret thematic gardens that allow for natural sunlight and a private relationship to the outside world.

The architectural approach is focused on the empowered daily experience of the three users who recreate their spatial limits within the mountain leave their physical and spiritual trace. Aligning the main roof with the mountain’s slope and creating a deconstructed, rocky landscape mimicking the hardscape in a contemporary vision allows the three users to appropriate the mountain itself. Creating complete freedom and intimate relationships with the natural environment that unleashes their creativity and spirituality through their own personal space.

Haven house is a revisited, contemporary vision of the gardens of eve.