21/013

Jessica Spresser

Architect

Sydney

«Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.»

«Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.»

«Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.»

«Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.»

«Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

I am Jessica Spresser and started my own – currently Sydney based – studio as an 'out of hours' outlet some years ago. The studio continues to engage in built and speculative architectural work, object design and fine art. I have always been a feverish maker of things, and therefore the studio has formed organically through the realisation of various experiments

Jessica Spresser

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

I grew up in a creative household. My father was a musician and my mother an illustrator/artist, so it seemed inevitable that I would pursue something related to the arts. I would never have survived in an intellectually repetitive profession. Architecture is gratifying in that sense, as it’s constantly having to reinvent itself, responding to shifting cultural and technological transformations.

The profession has lured me out of an ‘art for arts-sake’ mindset and encouraged me to embrace complexity. It is an entire ecosystem. Good design takes into account urbanism, politics, history and culture, as well as contributing something that is wonderfully idiosyncratic.

What are your experiences founding your own practice?

Starting a practice has of course had its challenges. There is an element of the ‘starving artist’ to it at times, for the sake of quality. I tend to combine practice with teaching, which I also find mentally rewarding. Returning to first principles alongside students helps to maintain a balance between the purity of an idea and the complexities of industry.

More recently, the office has won a national design competition for a public pavilion on Sydney Harbour. It is an exciting time for the practice, as the pavilion is in a prominent location, and has been designed to last for many generations. Competitions, particularly those that are blind-judged, are a satisfying way to approach a project. They are ideas-led, and the design intent is able to be preserved more easily than projects that are procured by other means.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as a location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your projects? What meaning does location have to you overall?

The studio is currently based between Sydney and Brisbane, but also has roots in London, Berlin and Japan. Sydney is providing some great inspiration at the moment, mostly due to its beautiful natural landscape. Australia is developing rapidly. Its population is expected to double within the next forty years, so well-considered architecture and urban design is critical.

While new commissions may be more accessible in Australia than in some other parts of the world, there are other considerations to be mindful of. Australia has an important indigenous history which has suffered significant neglect. There is also a real urgency for fast development, often at the expense of quality.

For me, living in Europe and Asia has thrown the profession into perspective, and I think we underestimate how influential ‘place’ and ‘culture’ can be on us as architects. I am pursuing a global rather than local mindset, despite much of the work being localised.

What does your working space look like at the moment?

The studio is akin to a small museum full of models, books, half-completed paintings and other experiments. It is a very creative space, and quite chaotic. We do a complete overhaul every now and again in order to start afresh on a new project or concept. Sometimes we listen to loud music or interesting podcasts, and at other times we’re much more introverted. It really depends on the task at hand. This has been one of my favourite aspects of establishing a practice: being able to manipulate my immediate environment to suit shifting creative pursuits and tasks.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

A mixture of quality, mindfulness and experimentation. I like the idea of designing spaces that outlast the original brief and function. The Pantheon is a good example; commissioned as a public temple by Agrippa, which was then converted to a Christian church, tomb, and public space. It has been able to withstand many centuries of societal transformation due to its own uniqueness and longevity.

Name your favorite…

Book/Magazine: I’m currently reading two books: ‘The Object’, which is a series of essays published by the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and ‘The Origins of Totalitarianism’ by Hannah Arendt. Both are challenging, and are inspiring new ideas.

Building: Out of the places I’ve visited, Teshima Art Museum by Ryue Nishizawa and the Pantheon in Rome. Both perhaps a little cliche, but are completely awe-inspiring nonetheless.

Mentor/Architect: I have been fortunate to have many mentors in the form of friends and colleagues. I spent a period of time in Tokyo working with both Junya Ishigami and Kengo Kuma, and while at university I was invited to work with Anupama Kundoo to realise an exhibit at the Venice Biennale. These experiences have been fundamental in forming my approach to architecture. I often also look to other disciplines for inspiration. Giacometti, Egon Schiele, and Frida Kahlo are favourite artists, each simultaneously fearless and vulnerable in their work and lives.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future? What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

Architects should have better knowledge of, and access to, planning policy and urban design. They are often the beneficiaries of commissions in which many decisions have already been made prior to their appointment. It can make societal change for architects difficult. For example, I have witnessed practices agreeing to undertake projects that are morally questionable, when they themselves are aware that a better model exists.

This also feeds into the issue of quality. A ‘race to the bottom’ in terms of time and cost is at its most prevalent. Long-term thinking is required of political leaders, but architects can also play a part. There should be a commitment to using sustainably sourced, quality materials. For us, there is a reluctance to venture into the realm of fragmentary architecture, which tends to both reduce remaining funds for more significant architectural pursuits, and be subject to ongoing deterioration and maintenance.

How do you perceive yourself as a female architect working in a male dominated field?

Gender inequalities, whilst undeniably present, are usually secondary to the task at hand, or the making of a ‘thing’ in my world. I think where imbalances and minorities exist, there is always a need for both advocates and operatives. Advocates do brilliant work to facilitate equality. Operatives are out there proving that discrimination has no grounds. I lean towards the latter, but appreciate those that spend time on the former. Parlour is an organisation that is doing fantastic advocative work in Australia and globally.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Explore as many ideas as possible, and don’t be afraid to discard the ones that don’t work. You will draw upon the better ideas for years to come. Read! Reading will help to generate both ideas and critical opinions. Don’t be too concerned about grades. Many of the better architects I know have failed, or come close, at least once.

What is your favorite building material and why?

I don’t have a favourite, but am finding that I enjoy experimenting with standard materials, and drawing out their idiosyncrasies. I’m also fascinated by the tension between the architect’s intent and the free will of the medium. The material always has a mind of its own, which can lead to a better, unexpected outcome.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

Since my time in Japan, I have used hand-built physical models as a primary design tool. These range from rough, cast massing models to finely constructed, detailed models. They have a different quality to machine-made or digital models, although I can appreciate both. I love the laboriousness of models, and how they force the brain to slow down. It’s a meditative process, through which the best ideas can form.

In our studio we use a combination of 3D modelling software, hand drawing, collage and physical models. A design is manifested through the use of all of these methods simultaneously.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

Architects need to juggle the physicality of what we do with the impact that this has on the world. We need to be much more conscious about the materials we choose as well as the projects we undertake. Australia is unfortunately trailing behind many other countries when it comes to issues on climate change and sustainability. Through teaching, however, I’ve noticed that there is a new generation of young architects emerging who are holding more established practices to account. They are focussing on social housing and good density models, working with recycled materials and challenging policy. The narrative that architecture cannot be both beautiful and sustainable is disappearing.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

Peter Besley. I’m working alongside him on some current projects, and his expertise ranges from urban to detailed. He is a brilliant thinker and designer. Peter has recently set up his own eponymous studio after having founded and led Assemblage in London for many years. Previously he led the design for the winning scheme for the Iraq Parliament complex in 2013, and more recently the Design District in Greenwich, London.

Project 1

Pier Pavilion

Sydney

ongoing

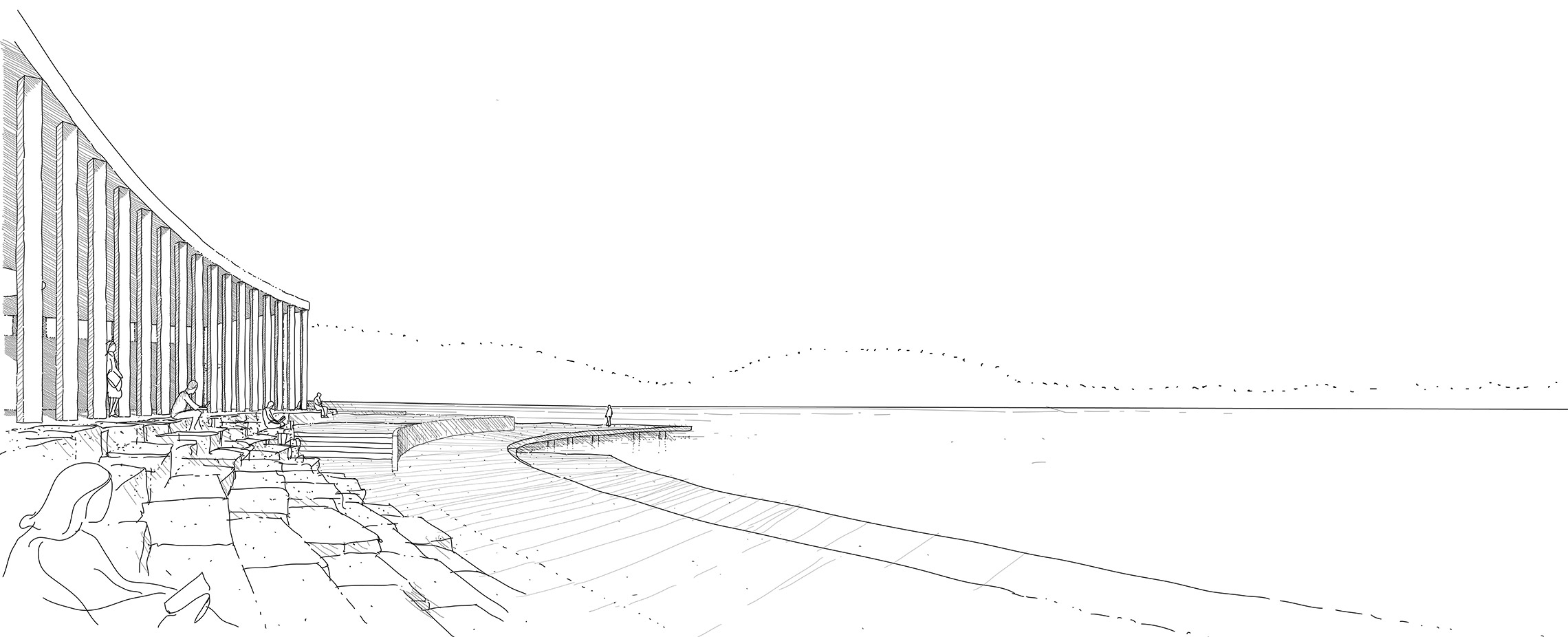

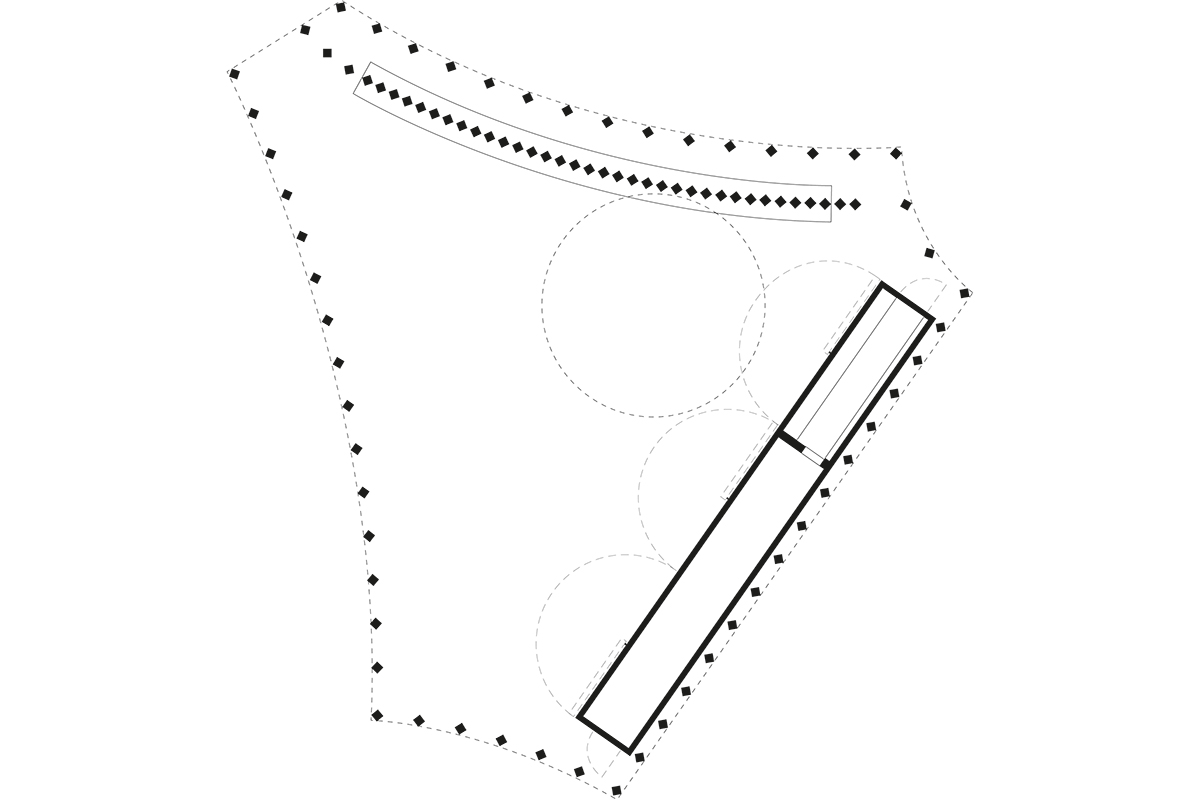

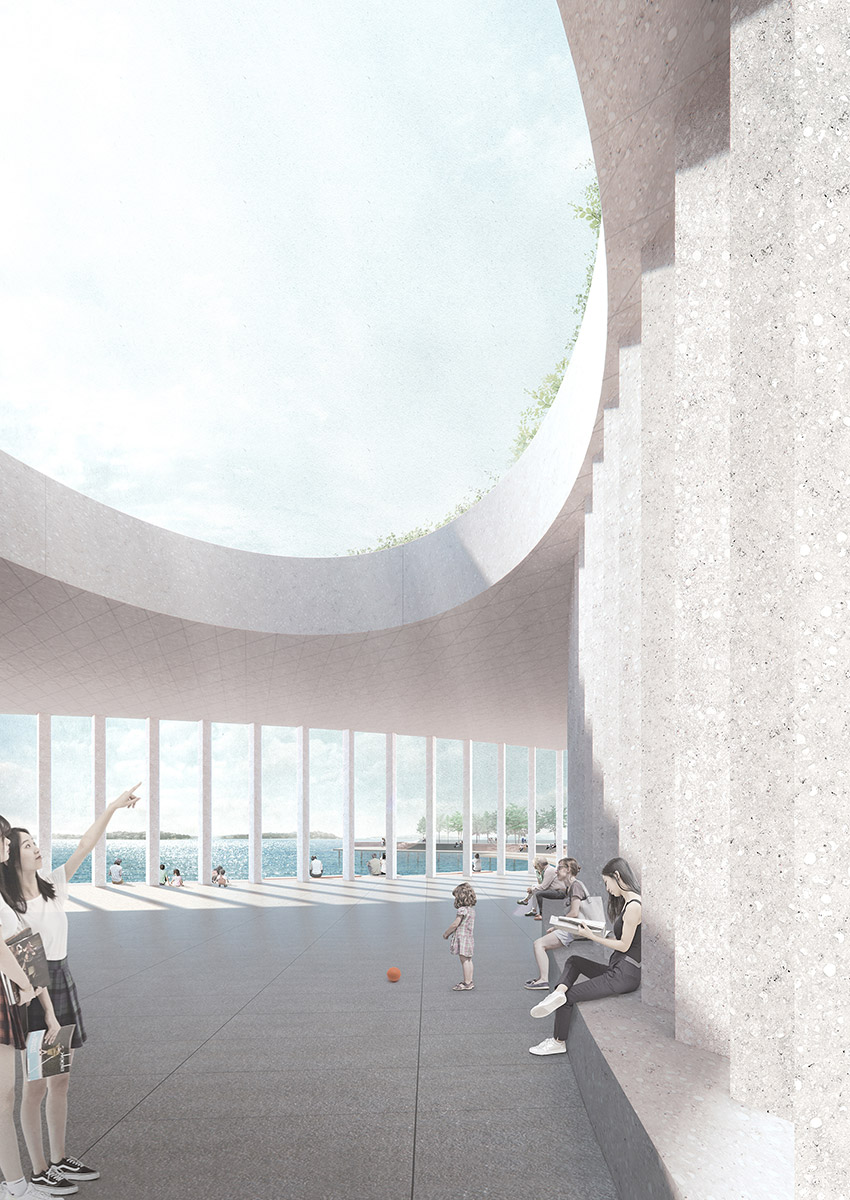

We have recently won a national competition for a new permanent public pavilion on Sydney Harbour in Australia. The project is a collaboration between the studios of SPRESSER and Peter Besley.

Made of recycled Sydney oyster shells, the Pavilion references human gathering by the sea. It is designed as a democratic gathering space under a landscape canopy and acts as a meeting place, a site for events, and a memorable part of the city.

The Pavilion celebrates elements that compose the site: land, sea and sky. Land is expressed through a democratic gathering space under a landscape canopy; its curved envelope analogous to neighbouring coves. Sea is experienced via materiality. Sydney rock oysters are mixed with white concrete, which is then honed to reveal the shell. Sky is understood through a large oculus puncturing the canopy, its perfect circle free of earthly geometries.

The project is due for completion in 2022.

Project 2

Ceramic Studio and Kiln

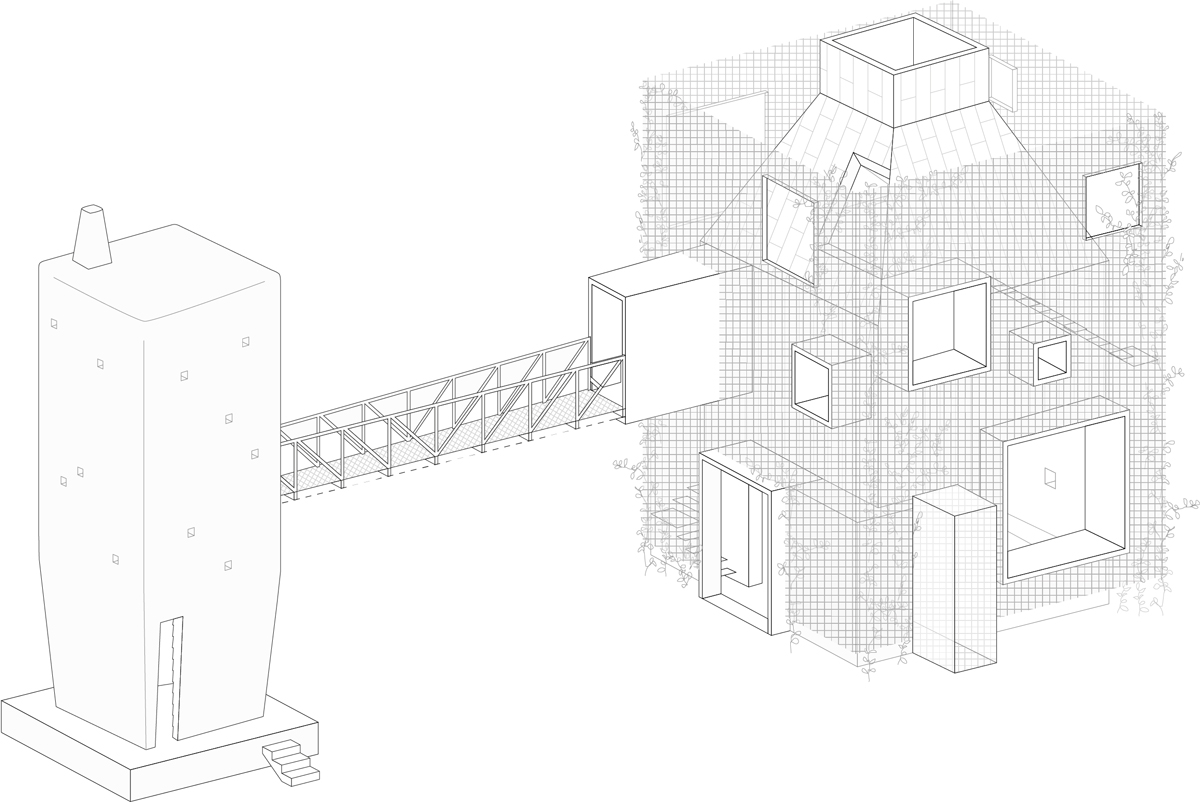

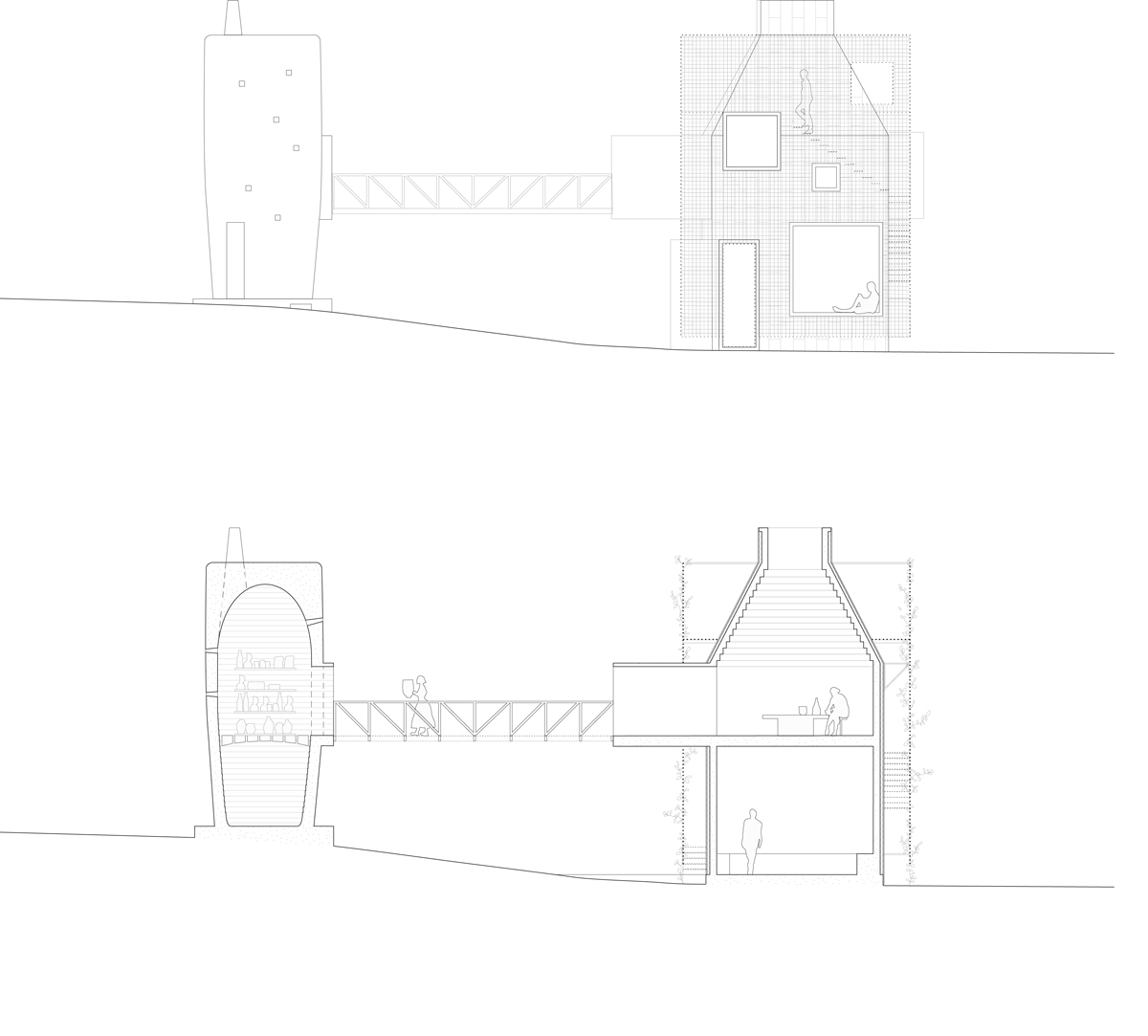

This scheme is a prototype for an alternate approach to suburban Australia. It is a studio for four ceramicists with a gallery space at ground level. The studio is connected to a large, wood-fired kiln via a steel gantry.

The diagram is a series of concentric, rotated squares, which accommodate utilities and circulation in interstitial zones. The inner square is positioned such that primary views are captured through a number of protrusions. Building materials reflect this place of tactile production; insitu concrete and handmade tiles form the primary walls. The studio is then cloaked in a fine steel mesh.

The project demonstrates the way in which productive typologies can invigorate and permeate dormitory suburbs. It is the result of an introduction of easements to suburban lots on the fringe of the city centre. Laneways are introduced into mid-block zones, allowing for subdivision and rear lot access for small businesses. The result is a network of active, pedestrianised laneways, mindful densification and a decrease in commuter congestion

Website: www.spresser.co

Instagram: @spresser

Photo Credits: © SPRESSER

Interview: kntxtr, ah+kb, 05/2021