21/016

RSL

Landscape Architects

Milan

«Designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.»

«Designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.»

«Designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.»

«Designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.»

«Designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

RSL is a landscape architecture practice founded in 2018 by Lorenzo Rebediani and Vera Scaccabarozzi. The studio is based in Milan (Italy) and works on the complex entanglement of the processes that define a landscape.

Both Lorenzo and Vera graduated in architecture at the Politecnico di Milano and specialised in Landscape Architecture in Genoa.

How did you find your way into the field of landscape architecture?

Vera: We started together in deep and constant dialogue on the border between architecture and landscape. I find that our practice is insisting in this marginal dimension: designing is not about us, but we are in the middle of a complex fabric of relations that we have to weave.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your time at university?

Vera: Dedication, curiosity, and the fruitful encounter with Lorenzo.

Lorenzo: I remember it was a time of conflict and search for identity. But truth can be found in conflict.

What are your experiences founding your own studio?

V: It took years to find a position on landscape design, a true and honest position that was really ours. That was the main difficulty for me. I got to know my masters over time, before, after and during university: the moment of education continues now more than ever. What they taught me to cultivate is doubt and honesty. I have learnt to listen. On this we are building a system of values that define our design practice in which we deeply believe in the need to listen both to the spirit of the client and to the stratified characteristics of the place, in order to translate them into a project that is able to weave a relationship between both.

The design dynamic is of course complex, specially if you have to deal with living material that requires a lot of time to be properly known, but it also gives some unexpected and unpredictable results. We are not alone in this process, and this is such a relief.

How would you characterize Milan as location for practicing architecture? How is the context of this specific place influencing your work?

L: Milan is a city where it is easy to practice the art of meeting. It is founded on a rapid and aesthetic culture and its rather contained dimension favors creative dialogue and the meeting of like-minded souls or professionals.

What does your working space look like?

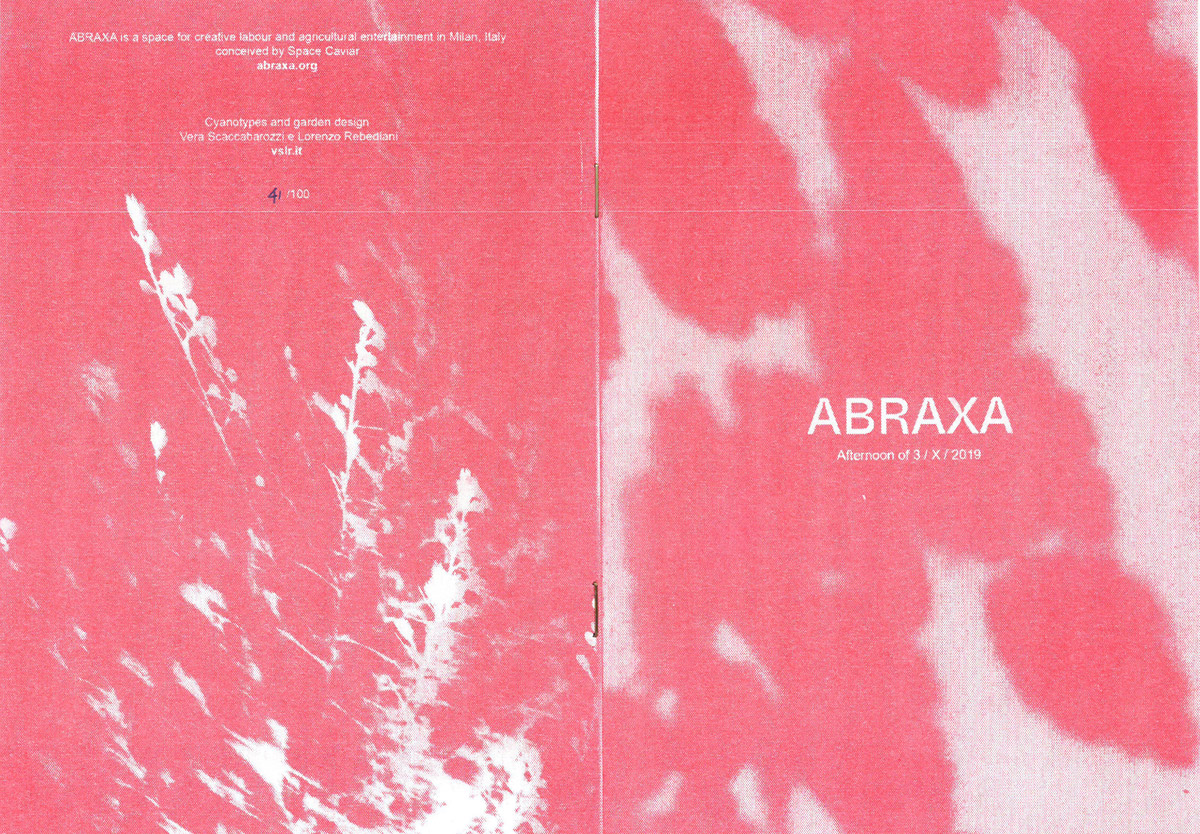

We have two locations for our studio, the main one is in Milan and it’s in Abraxa, a place founded by Joseph Grima (Space Caviar) where we share space with a community of other practices that work between architectural research, curatorship, design, art. We designed the courtyard – garden in 2019 and we moved there in 2020. It is an incredibly stimulating environment, where we feel part of a group of people that share a very curious and critical attitude, that challenges the limits of its practices and that is in constant dialogue.

In order to develop a more silent and contemplative work we have a second venue in Faggeto Lario, a small village on Lake Como in close contact with the landscape. Here we founded tònos, a critical observatory whose main activities are research-actions in ecotonal environments through residency programs and long-term research activities.

For you personally, what is the essence of space?

The moment in which the form coincides with the meaning.

Which material fascinates you (at the moment)?

V: In the last few months I have moved to a small village on Lake Como. Since then I have been observing the mist, in the Leonardesque sense of atmospheric dust. I am trying to understand how to ‘use’ this air stratification in our projects.

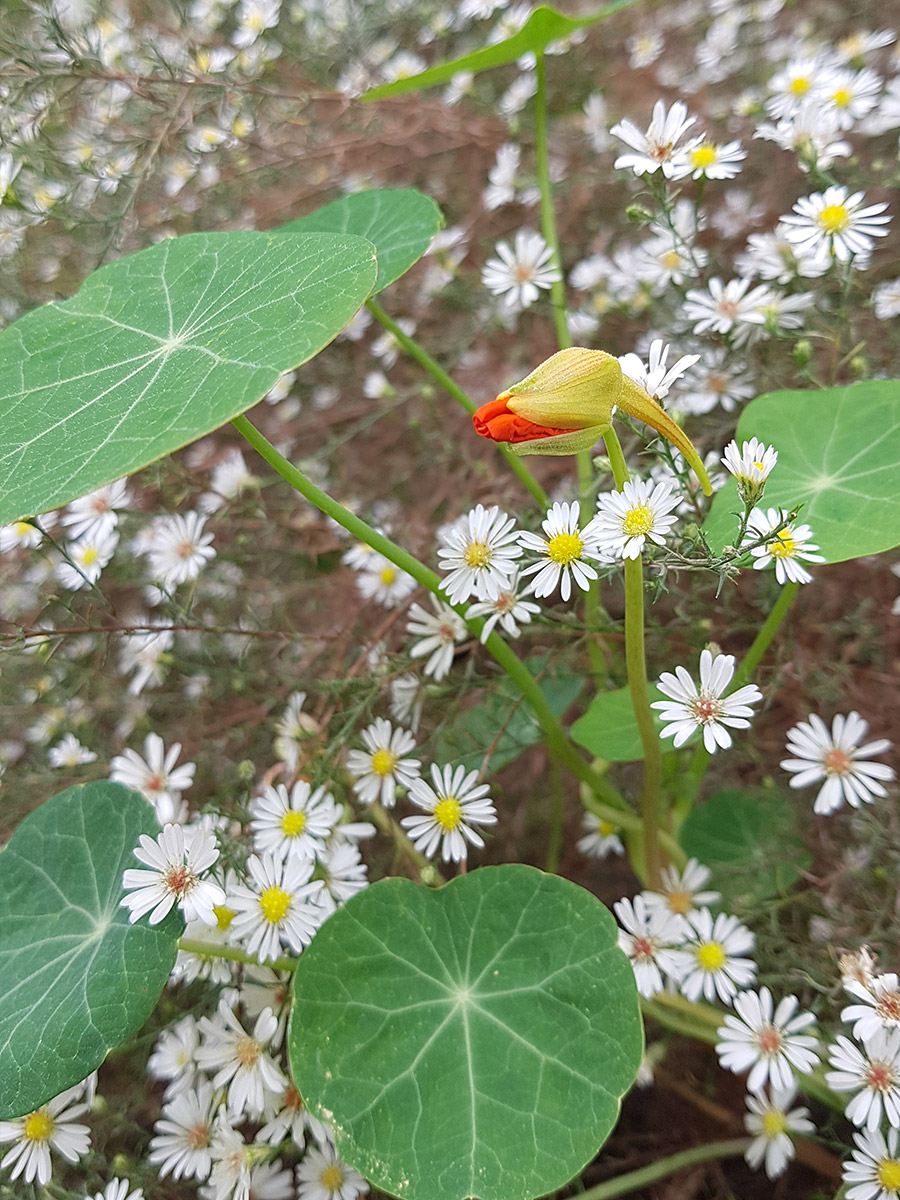

L: Through a project we are realizing for the art collector Frederic de Goldschmidt I found myself thinking about the analogy between clouds and plants as project material. Both can appear and disappear. We are used to attributing figures to clouds, according to the process of pareidolia, that is, the human faculty of seeing what is not there. To what extent can something absolutely ephemeral like atmospheric dust or a flowering become figure? And can this temporary form (signifier) register a meaning (signified)? Sometimes what we suppose eternal is fleeting and what we suppose fleeting is eternal.

Whom would you call your mentor?

L: My mentor was my grandmother’s garden: a small stream runs through it…few environments are richer in insights than wet ones.

Name your favorite…

Book…

V: In these last days it is ‘An Essay on Pan’ by James Hillman (1972).

Garden….

V: In these last days it is a garden that is not existing anymore: Greystone (UK) by Jorn de Prècy (XIX–XX century)

L: I’d love to return to Nara, Japan, practically a garden city.

How do you communicate/present your work?

What needs to change in the field of landscape architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

V: I don’t know what needs to change in landscape architecture, but I do have a position on what landscape architecture is capable of changing. I feel that there is a general flattening in the depth of views we have about our future and the future of our environment. I think landscape architecture is a tool to help us imagine the future.

The fact that working with landscape requires us to think on a larger time scale than we do, for interventions that we hope will survive us, makes me feel part of a much larger and more complex mechanism and gives me great optimism. When we design a garden or a landscape system we are in fact working with the future, trying to predict and shape it, we are triggering processes that will develop and evolve into an interconnected series of living scenarios. This creates a tension between the immediate present, that of constant care and attention to the smallest plant, and the more distant and elusive future, that of the ‘completion of the project’.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into?

V: Geoffrey Dutton, his work as poet and his work as ‘gardener’.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

L: It is very important to cultivate one's own individuality: the hyper-connected world we live in can lead to the homologation of skills and content, because, more or less consciously, we tend to follow the trends that connections makes obvious. Instead, diversity in achieving goals and challenges of the project, makes us human and I think it is a value.

Project 1

Gardens of Z33

House for Contemporary Art,

Design and Architecture

Hasselt, 2020

Architecture: Francesca Torzo

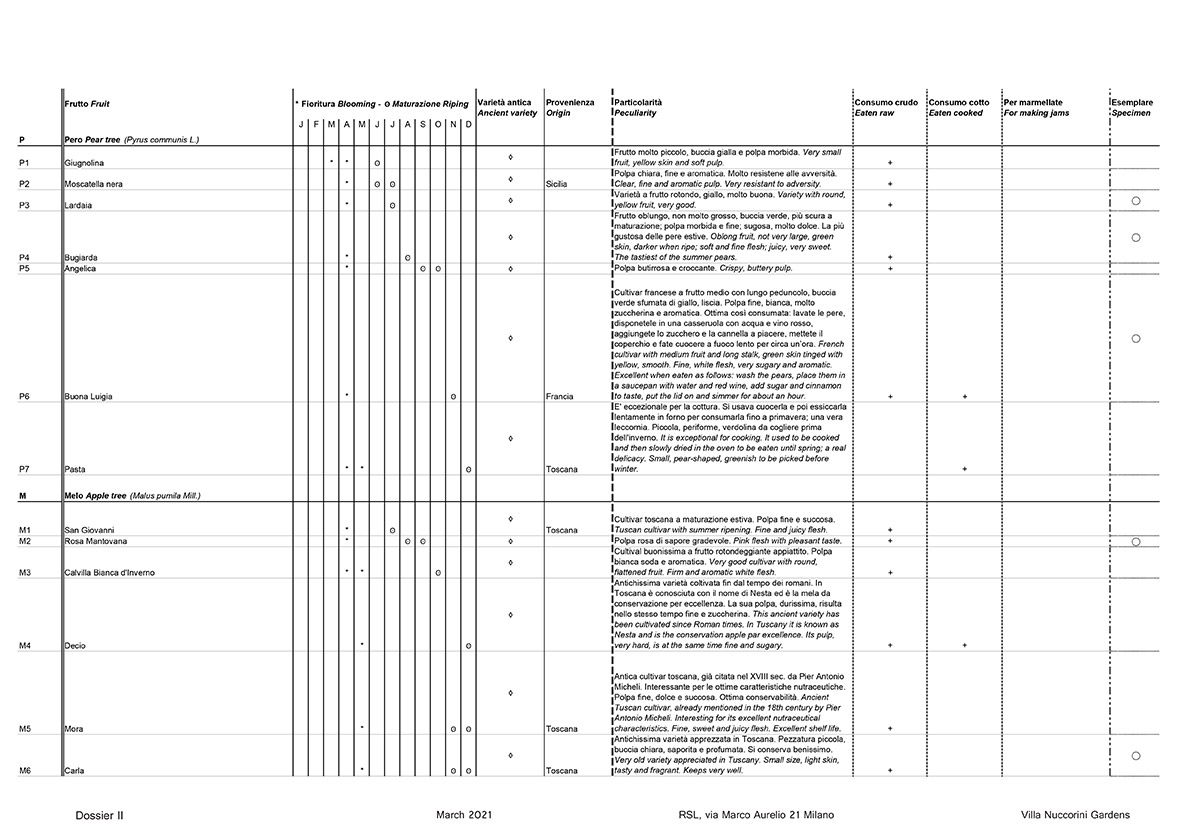

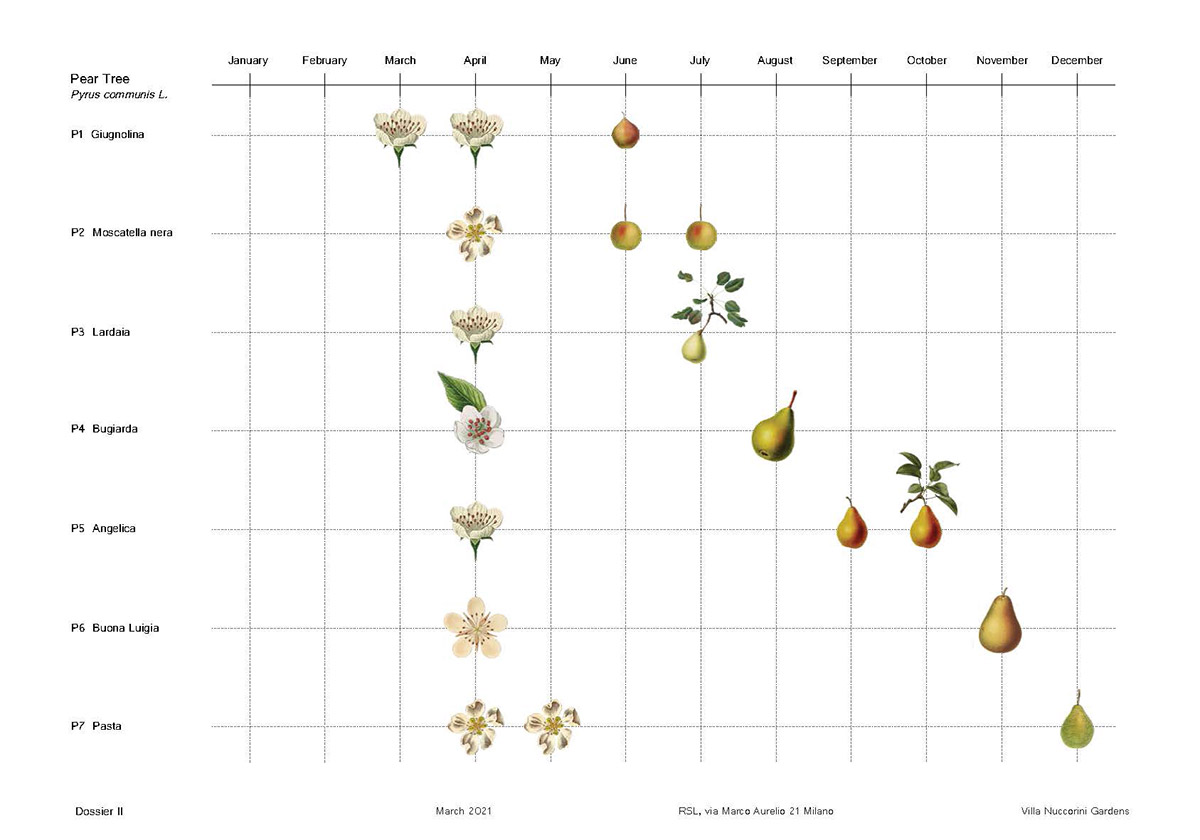

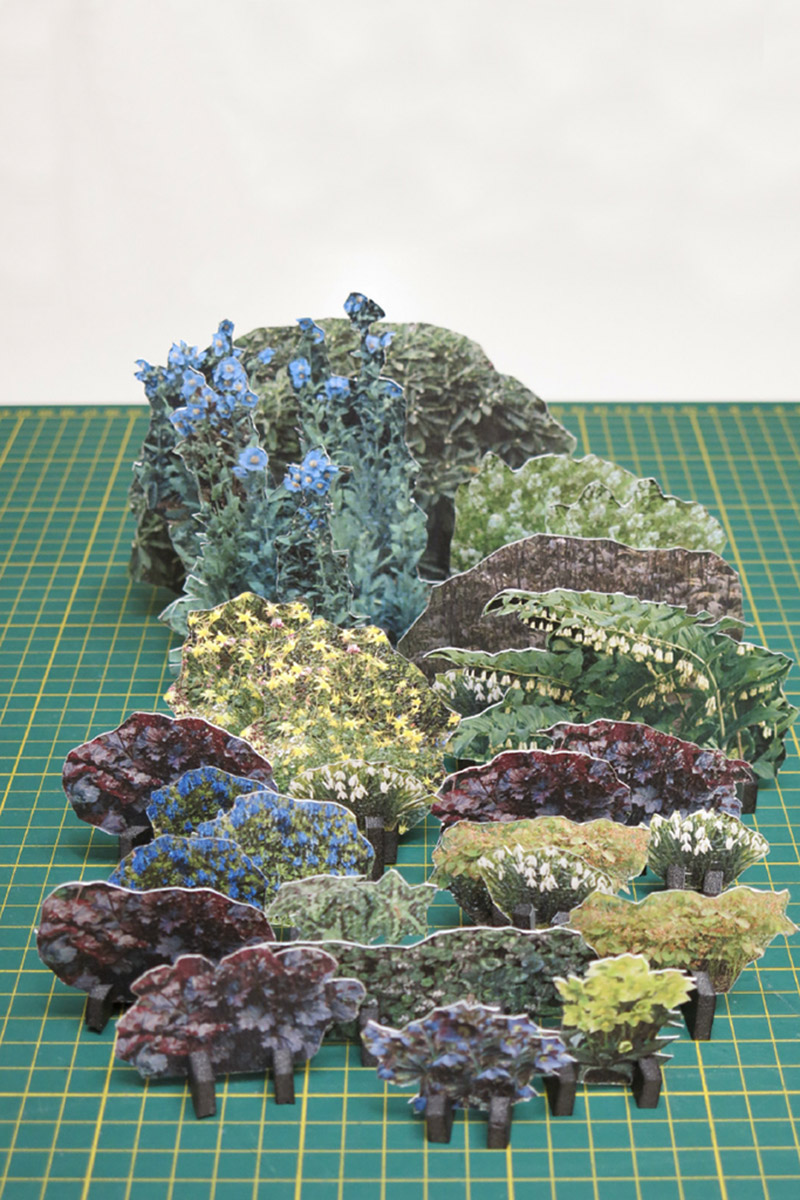

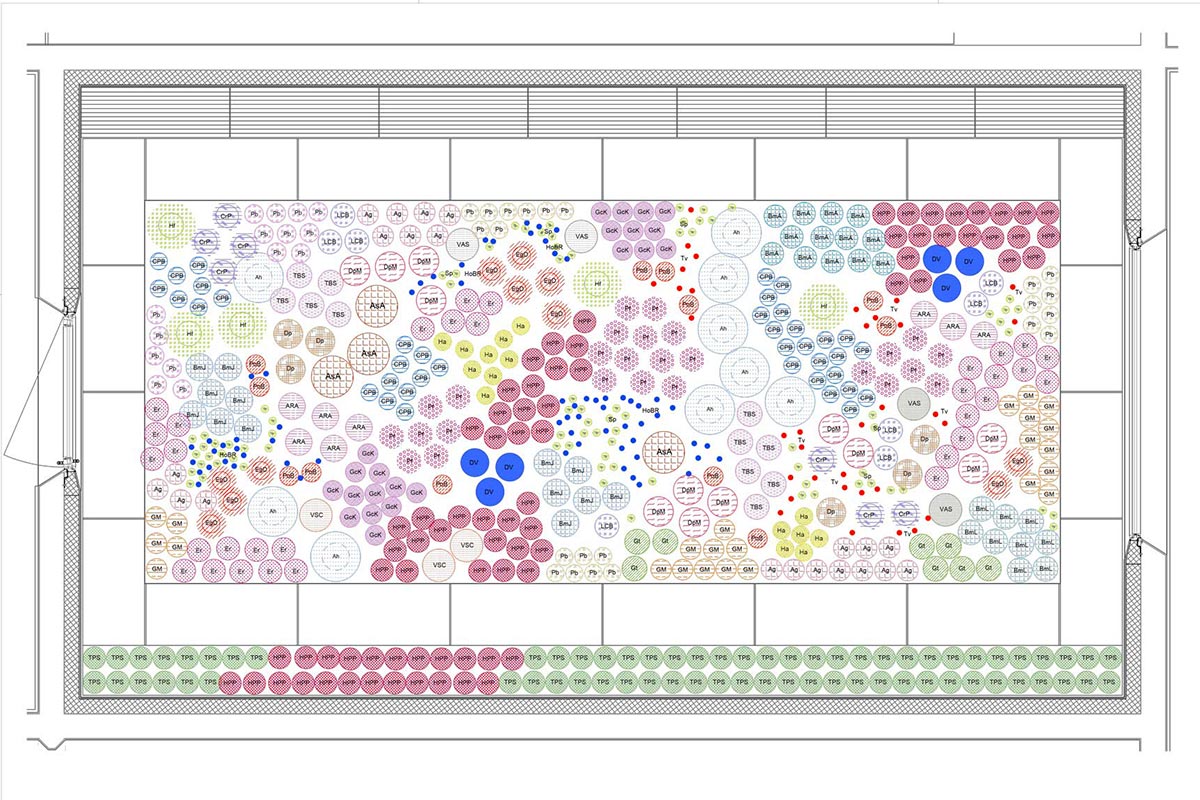

The new wing of Z33 contains four open rooms that are in dialogue with the sky. These rooms are inner gardens. The building’s program is characterized by temporary exhibitions and by public spaces that define a rhythm for the visitors. This same rhythm also sets the choice of plants, modulated to offer ever-changing scenarios. It is important to connect the frequency of visitors with the plant’s life cycle to create an empathic relationship with the gardens. Visit after visit one may fall in love with a scent, a wild complexion, or a leaf with audacious architecture. One may also miss the freshness of a flower that will not return until next year.

To design this scenario we considered each plant as a process instead of an object and intertwined these flows into iridescent gardens. Recurrent plants in all the gardens join together highlighting the spatial qualities of each one, creating an organism ‘in varietate concordia’ (defined by its variety). The gardens are all related, but each with their own personality. This project is the result of a precious and continuous dialogue with the architect Francesca Torzo.

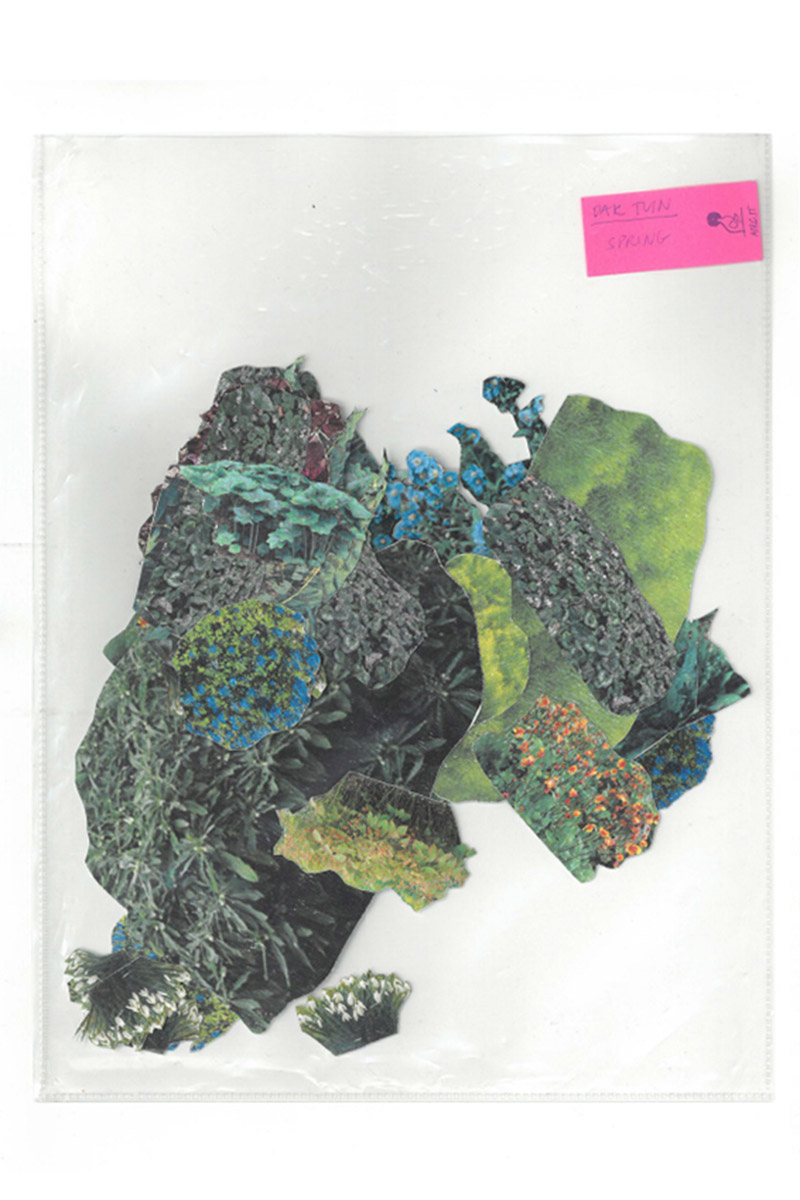

Reference

Studies

Plans

Process

Space

Project 2

Abraxa

Milano, 2019–20

In collaboration with Space Caviar

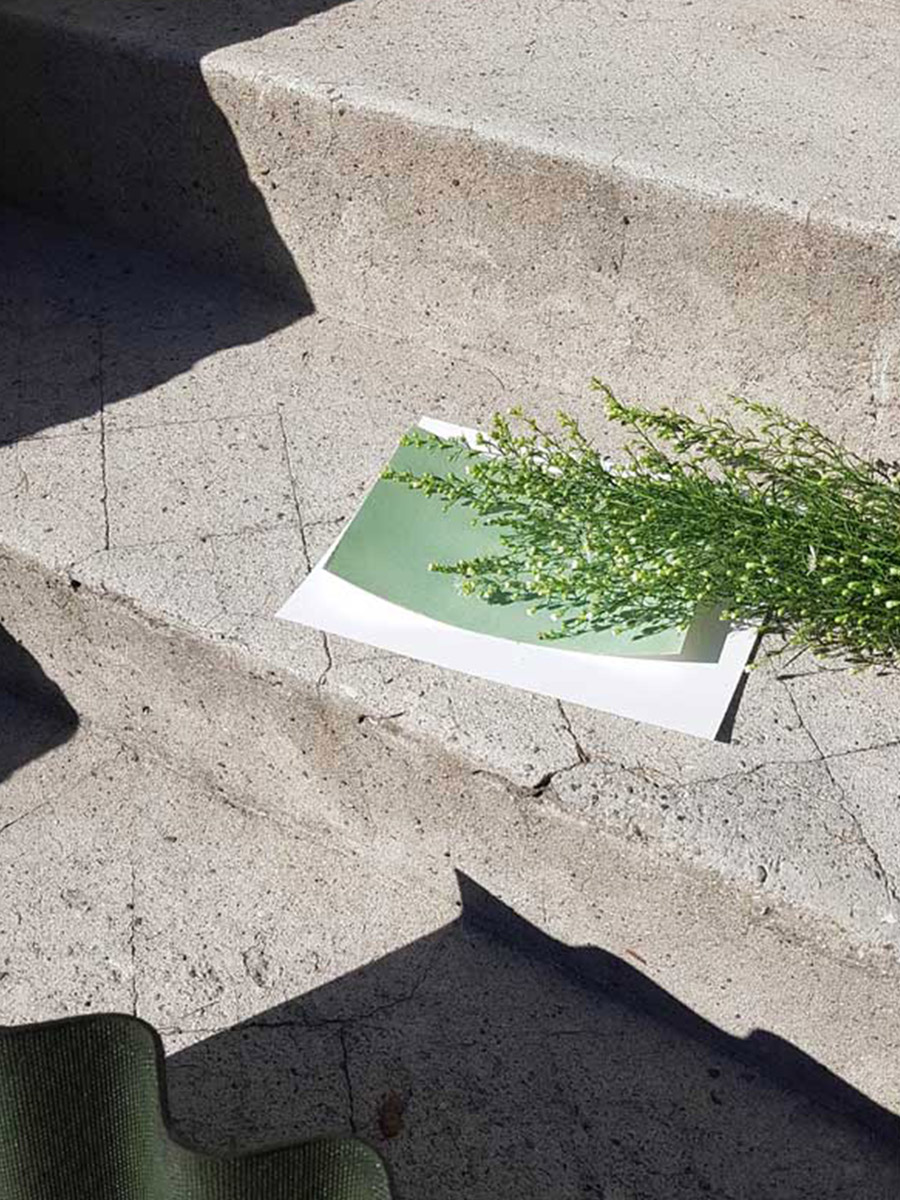

This garden was created in a former industrial court, now renovated as a workplace for architecture, design and art. The courtyard was a mineral surface made of concrete blocks, indistinct and hard. We proposed a simple and radical project, based on the gesture of removing one brick after another to discover the fertile soil underneath. Once the soil has been regained, it has to be taken care of with soil improvers and aeration, and finally you can start planting. These processes are designed to be low-tech, so the Space Caviar team could build their own garden. This kind of approach is the result of the relationship between the spirit of the client and the needs of the site that we have translated into this project.

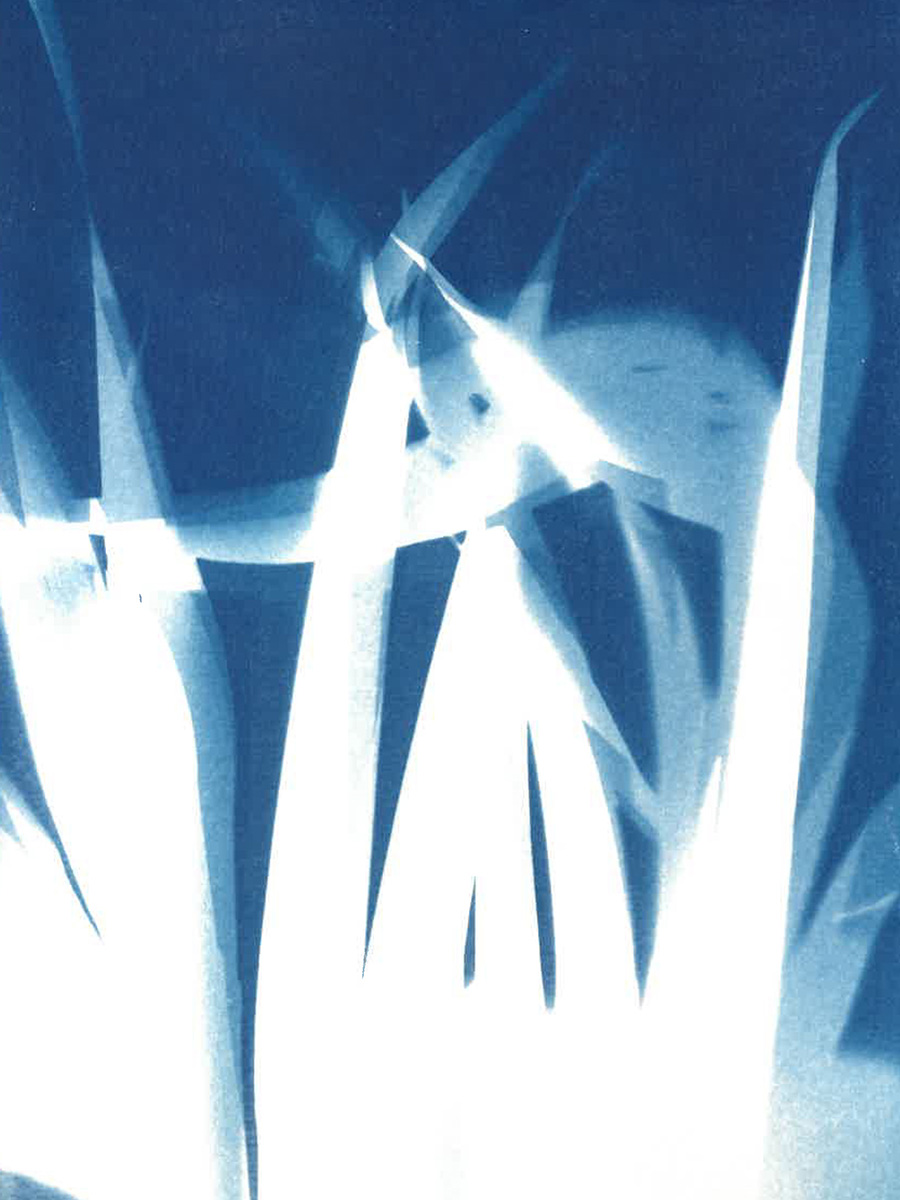

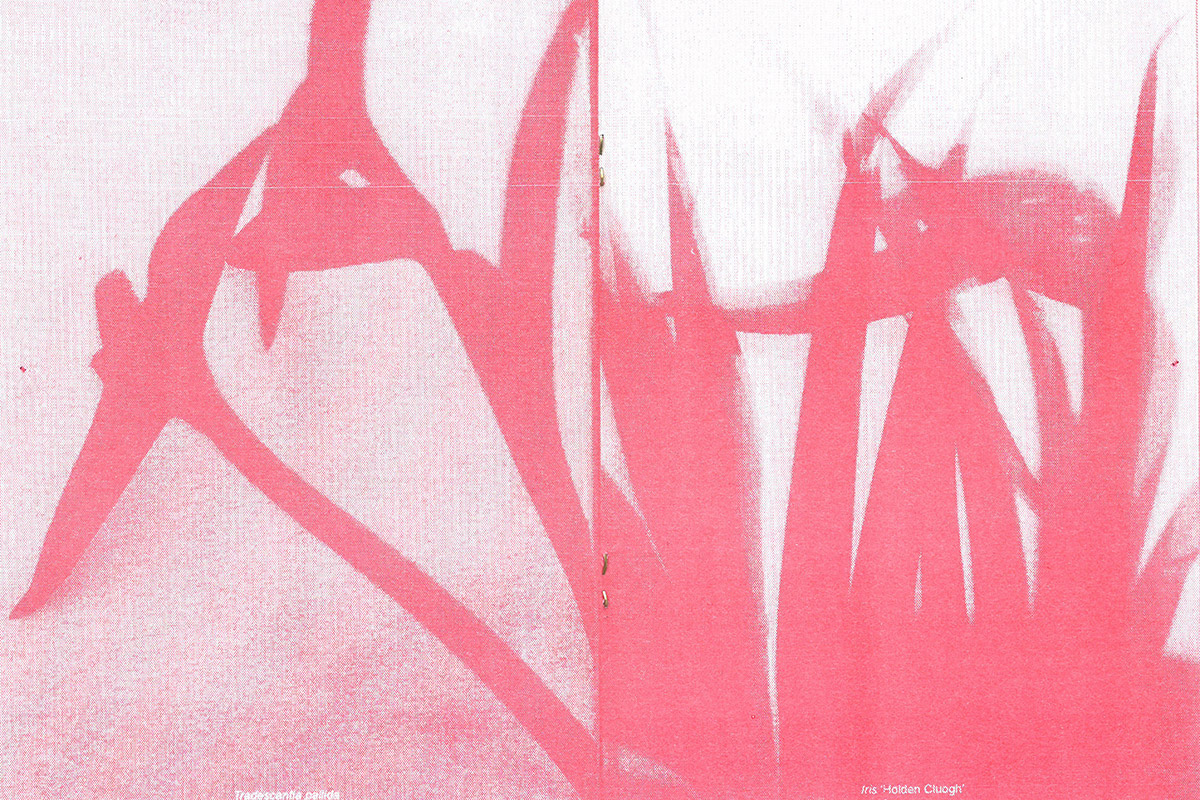

The project includes a lush space, where the stone paved ground is partially removed to reveal an enclosed fruit garden, and green islands of productive plants. The garden provides: a vegetable garden, medicinal plants and invasive plants that produce hege biomass for architectural purposes. Fruit trees bring shade and food for outdoor lunch meetings and create relaxing spaces for breaks. While planting we captured the first shadows that the plants made. The result is a series of 12 cyanoprints developed in the sink of the garden.

Drawing

Space

Documentation

Before

Website: http://rslandscapes.it

Instagram: @rsl_landscape_architecture

Photo Credits: © RSL, © Mario Giacomelli (B/W Reference Picture)

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 05/2021