21/020

André Tavares

Curator Garagem Sul

Lisbon

«Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying.»

«Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying.»

«Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying.»

«Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying.»

«Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying.»

Please, introduce yourself and Garagem Sul.…

I am an architect, and my practice has gradually led me into the areas of criticism, research, writing, publishing and curating. You currently find me working in my capacity as a curator at a Lisbon architecture gallery, located in the car park of the Centro Cultural de Belém (CCB), a leading Portuguese cultural institution. Garagem Sul has been exhibiting architecture regularly since 2012, and so far we have held more than 26 exhibitions, as part of the CCB’s mission of presenting architecture to a wider audience, which has been its practice since 1993. I guess I joined the team because of my ability to bridge the gap between the professional culture and the idiosyncrasies of architectural practice with a broader range of interests. When writing, one must be precise and incisive, and ultimately capable of addressing an abstract audience.

Everyone, whether they are architects or not, should be able to understand what you are saying. It was through my publishing work that I was invited, along with Diogo Seixas Lopes (1972-2016), to act as the chief curator of the 2016 edition of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, which we dubbed with the name of The Form of Form. Our strategy was to speak directly to the heart of architects – who believe in form, just as I do – while also making the event meaningful to a wider audience essentially interested in processes. In order to build a form, architects have to deal with a complex system of aspirations, technical possibilities, objective limitations, and so forth. Forms result from practices, and these practices are in a permanent state of friction in relation to society. Ultimately, these forms express the nature of society, as well as its paradoxes. In The Form of Form, our aim was to explore these frictions by embracing the expanded field of architecture without abandoning form. In a way, the work that I initiated at Garagem Sul in 2017 is a development of this hypothesis.

Garagem Sul attempts to raise awareness of the power of architecture among non-specialised audiences, and it grants architects a platform for demonstrating how their knowledge has the potential to transform society. This dialogue is materialised in the form of exhibitions, such as the At Home exhibition that we are currently presenting, or Our Land is the Sea, which preceded it.

André Tavares © Augusto Brázio

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and/or the extended field of architecture you are working and navigating in now?

Life has its own ways of organising things! My father is an architect, and I became part of the architectural world at a relatively early age. After completing my degree, I practised architecture for a while, winning a few second prizes in competitions and building up a small portfolio of enthusiastic clients. And then the various crises hit Portugal very hard. By then, I was part of a research team looking into urban policies: I started my PhD and was awarded a generous grant to live in Switzerland, after which I moved to Paris and São Paulo. Needless to say, all this moving around took me away from the office, and even further away from any future commissions.

On the other hand, I was having a lot of fun in my mind, and writing various materials that other people appreciated. When I finished my PhD on the presence of reinforced concrete in architects’ design strategies in the early 20th century, it wasn’t easy to find a job in the Portuguese academic world, and I tried publishing. Dafne Editora – a Portuguese-language architectural publisher that I founded with my father – had gained momentum by then, but I soon realised I had to keep on with my own research. And I kept travelling and researching.

In Montreal, at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, I started to plot The Anatomy of the Architectural Book. Back again in Portugal, at the peak of the economic crisis and together with a heterogeneous group of colleagues and friends, I published seven consecutive issues of Jornal Arquitectos. Heading the editorial board of an architects’ magazine was a great experience in learning how to deal with the professional challenges and devising a form of criticism that was not only professionally engaging, but also expanded the disciplinary field.

After the magazine, the Triennale was an opportunity for internationally broadening a debate that we were setting up locally in Lisbon. That was how I got involved in the work I’m doing now. You can imagine that there wasn’t much time left for architectural design and for maintaining an office-based practice. On the other hand, it was a perfect occasion for expanding my range of ideas, dialogues and interests throughout the world.

What are your experiences in being responsible for the programme and curation of an institution like the Garagem Sul?

We have limited resources and high expectations, and it is hard to find a balance. Also, by being a strong institution, Garagem Sul has both the benefits and the disadvantages of its scale: while the conditions exist for doing things you wouldn’t be able to do somewhere else – as is the case, for example, with expensive exhibitions – it is strangely complicated to do smaller things in an effective way – such as maintaining a blog or operating a swiftly reacting website.There are expectations and institutional responsibilities that prevent us from adopting a more overtly critical stance towards the local reality, but, luckily, there are other people who can do that, such as the wonderful case of Rádio Antecâmara, or Instituto. But we can be political in the long term.

In 2019, we hosted Sébastien Marot’s Taking the Country’s Side exhibition, which made it possible to equate architecture with agriculture, and, in 2020, we presented Our Land Is the Sea, a look at the architecture of coastal landscapes from a marine perspective. The two exhibitions emphasised the environmental role of architecture, a discussion that engaged society at large. We realised that, after that sequence,our audience wanted to know more about these topics, a dialogue that has spread to neighbouring institutions. MAAT is currently hosting a beautiful exhibition on Aquaria and our future programme. In 2021, we will be hosting an exhibition on Cycles, curated by Pamela Prado and Pedro Alonso, looking at how architecture engages with the material resources of the planet.

How did you manage to engage society at large and how did you realize that there was further interest in the topic / more than in other exhibition topics?

The public programmes, engaging schools and visitors, are the most visible feature of such public permeability. There are a few critical reviews, which are important considering a precise and knowledgeable feedback from within and outside of the field — for the sea exhibition it is for example worth noticing the review in the national newspaper Publico, and the review from the Swiss architecture magazine werk, bauen+ wohnen. But other, more subtle, feedback is how ideas intertwine in public agendas. For instance, as a consequence of the sea exhibition, Miguel Figueira, who was co-curating the exhibition with me, was invited to be part of a local commission on the New Bauhaus. It was not without surprise that many of the discussions we had while preparing the exhibition were elevated to the level of policy debates: evident in the manifesto they published. This was a rather immediate reaction – usually ideas take way longer to percolate. Of course, we did not invent the sea, but the exhibition was timely and contributed to the manifesto that is now having its own life.

Your current exhibition is called At Home. Projects for Contemporary Housing. Why did you pick this topic and why do you consider it important?

The exhibition had already been presented in Rome by MAXXI when we decided to bring it to Lisbon. But, after being literally “at home” during the pandemic, we realised we had really hit the spot: it is a timeless topic, and, for the worst reasons, everyone is now realising its importance. The demographics are changing: would the pandemic have hit the elderly so hard if old people’s homes had been carefully planned and thought about, which is clearly not yet happening? The functions are changing, too: would a more flexible organisation of standard houses have prevented the currently uncomfortable conviviality between work and domestic life?

The sense of community is changing: the conventional family is no longer the sole reference for the way we live. What kind of houses function best for the new forms of social organisation? And yet the banks continue to only finance the standard home in a building with a vertical staircase, two apartments per floor, three-bedrooms towards the back, and a living-room plus a kitchen towards the front.

As society, we are living in a world of financial products, and do not build houses anymore.The real estate market is driven by decisions based on profitability and architects are not having any influence anymore as they stopped being in charge of housing policies. In Portugal, the state is announcing a large-scale EU-funded recovery programme (known popularly as the “bazooka”) to relaunch the post-pandemic economy. Of course, building is a top priority – I wonder why reforesting or re-naturalising is not, I am sure this could also prop up the economy – and housing is one of the policy areas that still needs to be resolved.

Still, it seems that contracts will continue to blindly favour operations conducted by construction companies that are applying already “tested” solutions. We know that such solutions have had their time and that they are limited. Architects had been thinking about this long, long before the pandemic, yet they are hardly part of the discussion about potential solutions now.

This exhibition is a testimony to that accumulated knowledge. I am not so naive as to imagine that this exhibition will lead to any immediate changes in the Portuguese housing plans, but it may help to raise awareness about the need for an urgent debate, and to transfer arguments and knowledge to an audience of non-architects, who ultimately are the ones responsible for the transformation of building practices.

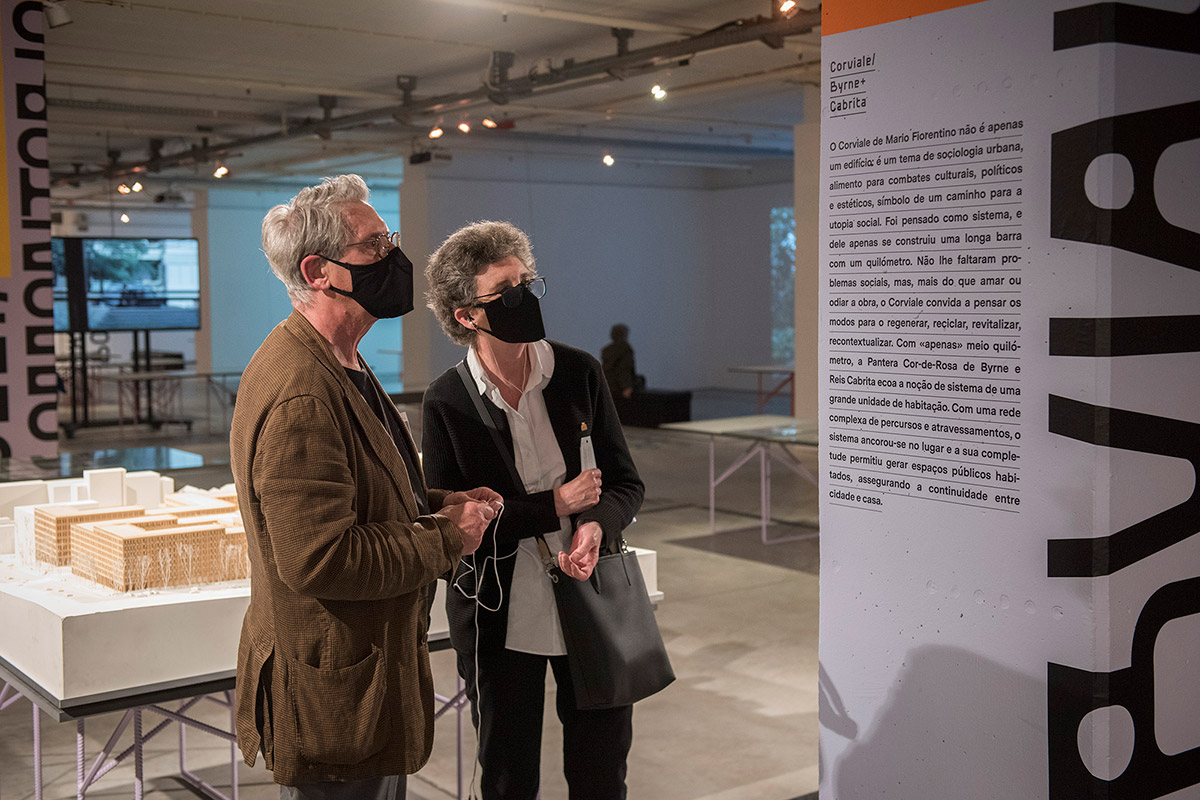

At Home. Projects for Contemporary Housing, April 16 to September 5, 2021. Garagem Sul, CCB, Lisbon, Portugal.

© Courtesy Garagem Sul, CCB, 2021 Photo: Tiago Casanova

At Home. Projects for Contemporary Housing, April 16 to September 5, 2021. Garagem Sul, CCB, Lisbon, Portugal. © Courtesy Garagem Sul, CCB, 2021 Photo: Tiago Casanova

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as a location for practising architecture?

It is tough in Portugal. The economic crises of the 2010s brought fees crashing down below the limit of professional viability. Technicians can “compete”, but architects are doomed. On the other hand, the technical demand has increased; more and more responsibilities are being placed on architects without their being given the related capacity to lead the building process.

Bankers and lawyers have more power over the building site than architects. The administrative bureaucracy is getting ridiculous, spreading responsibilities to all kinds of people to avoid any kind of liability. Thus, instead of supporting architects in the management of conflicting interests, it just pours even more gasoline on the flames. The few state commissions that exist are apathetic about architectural quality – there are almost no public competitions, there is no public discussion about the physical form of architecture whatsoever, and most commissions are selected simply because they have the lowest price, firstly in terms of design fees, and then in terms of construction.

As you can see, I am not painting a very pretty picture. You can find much more robust architectural scenes in any European country you care to mention. We still have many talented architects; we see lots of brave new architects striving to invent new forms for the practice of their art in order to survive in this jungle. And, you know, Lisbon is Lisbon, or Porto is Porto; there is the sea, there are fish, and the weather is nice. And, despite all the flaws, we do have a balanced society. You must come and see for yourself. We need knowledgeable critical views from outside, I am too deeply enmeshed in it all to have the necessary distance. Maybe that’s why I’m so pessimistic.

What does your desk/working space and exhibition space look like at the moment?

My desk looks like a mess. But my desk is in Porto. I’m sending you a picture of the team during the opening of the Our Land Is the Sea exhibition, a few days before it closed in March 2020, just before everyone had to wear masks. We are a small team of five: me, working just one day a week; Madalena Reis, who is our leader and is in charge of various departments at the CCB; then Margarida Ventosa, who produces the exhibitions, Inês Marques, who directs the public programmes, Diogo Nunes, who bridges the various gaps existing between all of us, and the CCB itself: communication, finance, management, etc. We then rely on the support of the larger team at the CCB, and on guest curators, architects, designers, editors, and so on, to help us imagine and build the content of exhibitions. And our collaboration with other institutions is of paramount importance, as, for example, with MAXXI in Rome; and this will also be the case with CIVA in Brussels for the At Play exhibition that we’ll be opening next September.

Are there other institutions which you perceive as a role model/good example? How do other cultural institutions influence your work?

My most cherished institutions are books. In books, I find the capacity to build up complex ideas and travel through space and time, they combine individual aspirations with collective interests. In order to reach the bookshelves and the hands of the readers, books require a network of collaborators, ranging from designers to printers, publishers and funding partners, photographers and editors, an endless parade of contributors. You don’t even need to read a book to be influenced by its content, and its material presence is all pervasive.

Think of Nikola Jankovic and the work he has been doing at éditions B2 in Paris: he is a radical independent publisher who doesn’t depend on any wealthy institutional support. With his customary modesty, the book series he has been publishing brings together an extraordinary range of ideas, old texts and new authors, established scholars and mavericks, and it’s pushing the boundaries of the architectural field. I love institutions that make unexpected things happen, and from whom we can learn.

In my own personal path, being welcomed as a researcher at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal was decisive in enabling me to learn this sense of culture as a collective endeavour, discovering how it can be socially relevant and acting as a bridge between professional and disciplinary knowledge.

For you, personally, what is the essence of architecture?

Building. Building is an activity that opens up all the possibilities of architecture, even the most wonderful, never-to-be-built, fundamental contributions. These only exist because we build. All the social and transformative capacity of architecture – where its real power lies – depends on the idea of building.

Exhibitions

CCB – Garagem Sul

2018 – 2021

Lisbon

At Home | 2021 | © Augusto Brázio

Production: Garagem Sul / Centro Cultural de Belém in collaboration with the MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts

Our Land is the Sea | 2020 | © André Cepeda

Curators: Miguel Figueira & André Tavares with Pedro M. Borges, José Albergaria, Rik Bas Backer, Marta Labastida, Ivo Poças Martins & Pedro Bandeira

Building Stories | 2018 | © André Cepeda

Curators: Rodrigo da Costa Lima e Amélia Brandão Costa with Maio, Ricardo Bak Gordon and de vylder vinck taillieu

Website: https://garagemsul.ccb.pt / www.andretavares.eu

Instagram: @ccbelem / @andretavares_2007

Photo Credits: All images © Courtesy Garagem Sul, CCB unless stated otherwise

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 07/2021