23/007

Material Cultures

Architectural Practice

London

«The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies.»

«The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies.»

«The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies.»

«The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies.»

«The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies.»

Please, introduce yourself…

Material Cultures was founded to bring together design, material research and high level strategic thinking – looking at materials, the political economy of supply chains, building systems and so on – to make meaningful progress towards a post-carbon built environment. We provide design services, undertake hands-on construction and refurbishment projects, and work with public, private and third sector organisations interested in developing and delivering a regenerative, low-carbon built environment. The three of us (Paloma Gormley, George Massoud and Summer Islam) run Material Cultures together.

Portrait – Material Cultures – © Ryan Prince

How did you find your way into the (extended) field of architecture you are working in now?

In our work we have always engaged with the act of building, working with our hands and being curious about where our materials come from. I think we also always shared an unease with the status quo, working within an industry of overwhelming inequity. These shared interests brought us together, and over time the tools we have felt we needed to tackle the environmental and social problems we are passionate about have broadened.

We are architects, but we don’t exist in isolation and working across research, technology and material science to us feels increasingly urgent and necessary. We design buildings with a holistic understanding of the regional landscape they sit in, from the crops grown to produce them to their reintegration at the end of their life. This requires an in-depth understanding of what materials can be drawn from the context.

How do you combine your work as architects with your research and publication work? What is the most interesting thing/unusual occurrence/greatest challenge you experienced working in both areas of the field?

The design and research work we do is so integrated now, each strand informing the other – a design problem sparks a research interest, and research work uncovers new areas and interests of design. We are very privileged to be able to work in this way: we are always learning.

The inertia within the construction industry is really extraordinary. It’s such a conservative industry and attempting to change the practices and structures within it can sometimes feel overwhelming. At the same time, on a day to day level working to overcome ageist, sexist and racist structures that we encounter can make the work feel even more daunting.

Constructive Land – © Jess Gough

How do you understand the relation of theory/reflection, practice and teaching in architecture?

Architectural education and theory as we experienced it is uninterested in the political networks and economy of its materials and building systems. Teaching has been a key space for generating knowledge and critically engaging with non-extractive frameworks of research, pedagogy and design. The intersection between practice and theory is key for imagining an alternative future of regeneration.

The construction industry is a major contributor to toxic air pollution and landfill waste. Business-as-usual building materials are part of an extractive political economy of supply chains and building cultures. The architect can be operative in building a future rooted in regenerative principles and solidarity economics. The construction industry is a major contributor to toxic air pollution and landfill waste. Business-as-usual building materials are part of an extractive political economy of supply chains and building cultures.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your work?

London is a fantastic place to be an architect. There is a vibrant culture of practice, teaching and discourse. We work in East London, on the fringes of what was once the industrial city. Being near to those places that were once central to production and manufacturing is a constant reminder of the value of those spaces within a city, and a cautionary tale of what can go wrong when capital development projects don’t engage with history, people and place.

Name your favorite …

Book/Magazine: We are currently reading The Land magazine. Finished listening to Untelevised:the Podcast last year – there was a series on the land that was fantastic. We also love the book: The Toaster Project by Thomas Thwaites

Building material: Currently we are obsessed with straw thatched roofing, we are having a great time learning about it and how the changes within industrial agricultural practices have limited the diversity of thatch types available, and made what was an inherently local practice into one influenced by global supply chains.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you?

We think it’s critical that we as architects understand the consequences and implications of the way we build; acknowledge our role in perpetuating harm; and accept that as architects we are uniquely positioned to positively influence not just material choice on building projects, but positive employment and labour practices both in the office and on the construction site.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Be curious: There is so much to learn from indigenous knowledge and building practices around the world, from how to build with what you have to hand, to how to build in low impact ways and adapt the way we live to the climate we inhabit.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone? From your perspective: What are the (political, legislative, etc.) influencing factors that matter (restrict/enable sustainability in architecture) most?

The entire industry and its supply chains need to be involved in a transition to more circular and biobased construction economy, from contractors to policy makers, saw-mills to construction skills academies. The most effective levers however are in the hands of the state – policy level change is one of the strongest tools we have to incentivise change in what is an otherwise conservative industry.

Architects are uniquely engaged with different actors along the supply chain and across the industry, through our own work and the way we engage with other actors we can both demonstrate best practice and also demand better practice from our collaborators.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

Ingrid Pollard

LION (Land In Our Name)

Landworker’s Alliance

Organic Lea Worker’s Cooperative

Project

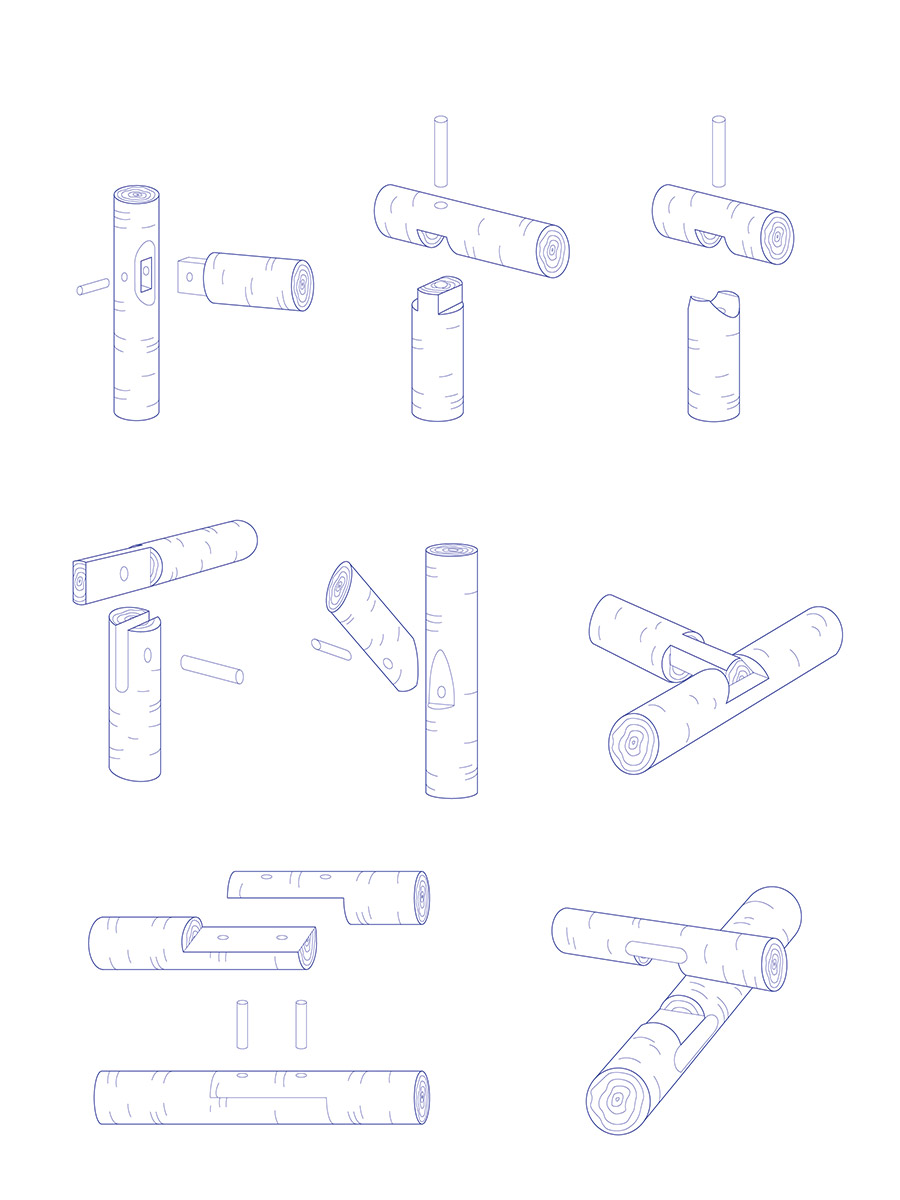

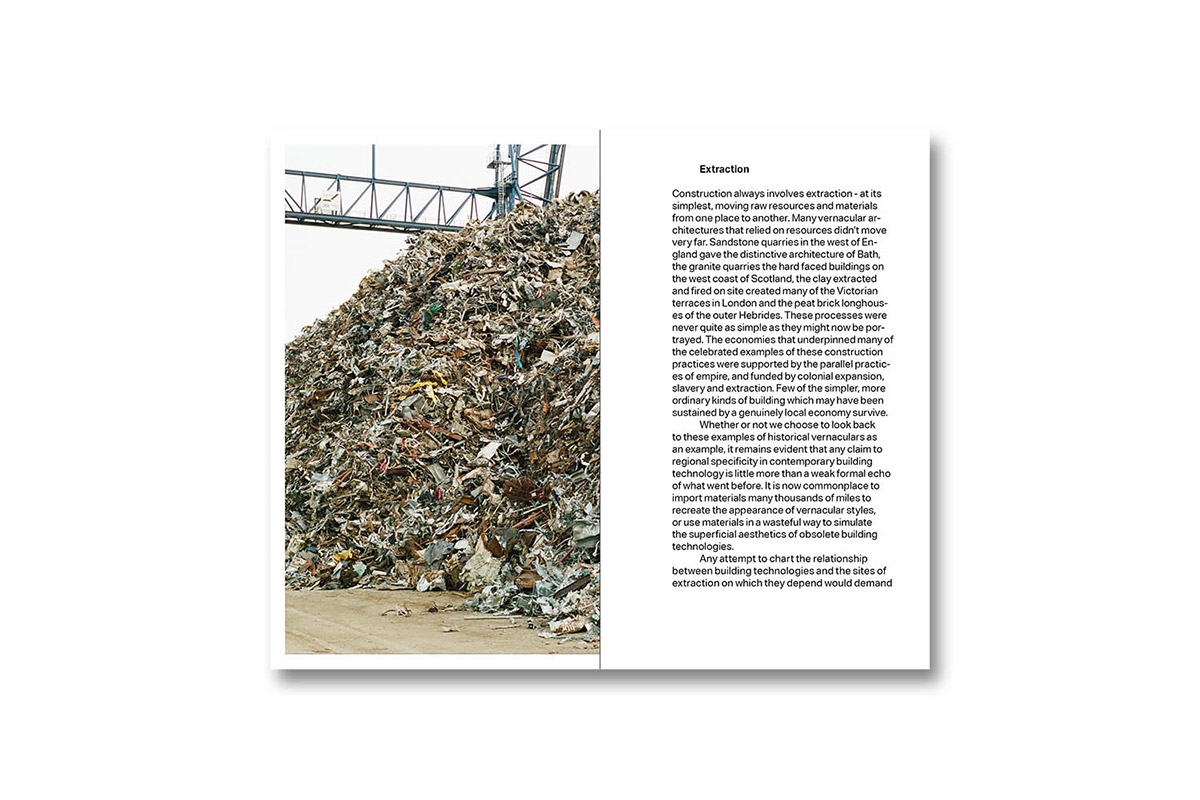

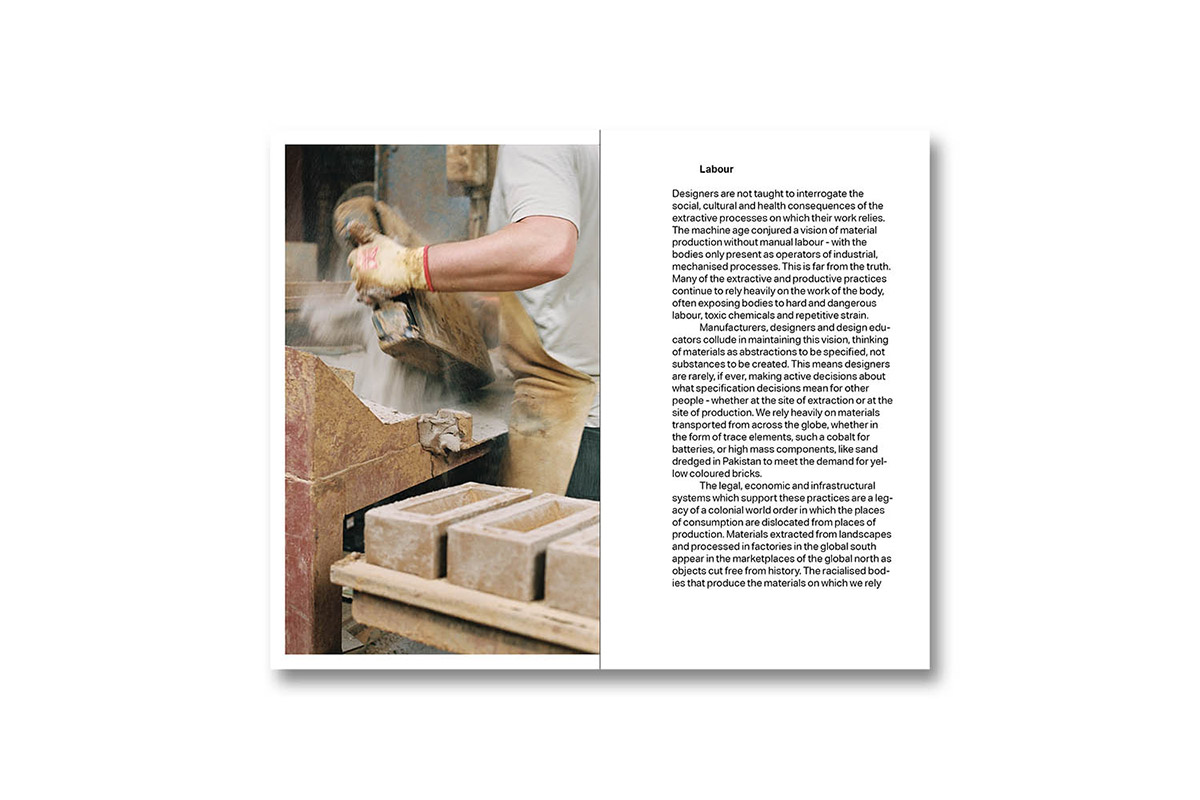

Material Reform

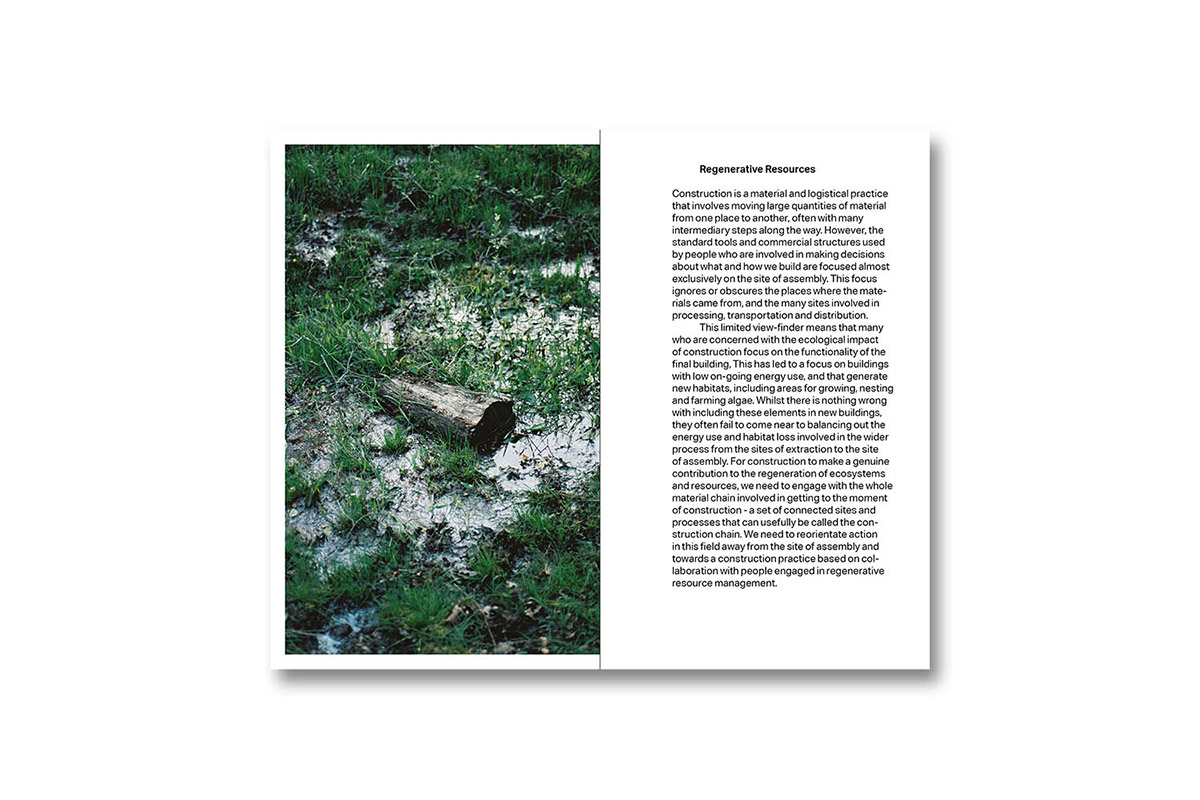

Our recently published book, Material Reform, presents a set of instructive and challenging perspectives drawing directly on the dialogues and tensions that we encounter in our day-to-day work. Texts centred around key concepts including labour, time, maintenance, language, land, and touch are interwoven with a visual essay reckoning with the processes that have transformed industrialised landscapes at different scales of experience and resolution.

Through text and images, concepts and practice, this book explores how developing a direct relationship with materials can help us find new languages with the potential to supersede those we have inherited from a narrow lineage of authors. These discursive threads come together to form a vital sourcebook for rethinking our relationships to materials, land, and development, in all their crucial intersections.

The book was co-authored with Amica Dall, and the photographs in the book are by Jess Gough.

Website: materialcultures.org

Instagram: @material_cultures

Photo Credits: © Mateial Cultures, unless stated otherwise

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 04/2023