25/004

Frankfurt Babylon

Online Journal

Frankfurt

«So, what does architecture is political actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse political with socially influential.»

«So, what does architecture is political actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse political with socially influential.»

«So, what does architecture is political actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse political with socially influential.»

«So, what does architecture is political actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse political with socially influential.»

«So, what does architecture is political actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse political with socially influential.»

Please, introduce yourself and your project…

Hi, we are Sandra Doeller and Benjamin Pfeifer, two of the founders of Frankfurt Babylon. Along with Carlos Becker and Benjamin Semmler, we are a group of critics writing and reflecting on urban planning in Frankfurt and in other cities. Our professional backgrounds are quite diverse: Sandra is a graphic designer specialising in book and exhibition design, while Benjamin Pfeifer’s background is in architecture communication. Together with the other Benjamin, a civil engineer, and Carlos, a political philosopher, we form an interdisciplinary group in which each of us has their very own angle on architecture and urban design.

Frankfurt Babylon is a forum dedicated to the critique of contemporary city planning and rebuilding. We explore urban spaces and emphasise the shortcomings in the design of newly built districts and other public areas. We are focused on the relationship between the built and the social – between urban design and social use. Some of the questions that arise in our work are very practical but rarely asked: Why do public benches no longer have backrests? Others are more theoretical: What role does a public square play today? What is urbanity? With Frankfurt Babylon, we use a variety of mediums to address these topics. We write reviews, essays, and commentaries, use photography, and plan to produce podcasts. All of this comes together in our new online journal – Frankfurt Babylon.

How did you find your way into the fields of architecture and architecture discourse?

Benjamin: I studied architecture and quickly became disillusioned with the field. The architectural ideal seemed focused on solitary, freestanding buildings, while urban planning was approached in a purely formalistic way. How are isolated buildings supposed to create urban spaces? During my studies, no one seemed really interested in this issue. When I moved to Frankfurt’s Gallusviertel in 2010, I observed the development of the nearby Europaviertel, one of Germany’s largest inner-city new-build districts.

One evening, Carlos and I went there with a beer and sat down on one of the few public benches. The bench was wedged between the entrance to an underground car park, a ventilation shaft, and a private garden. Next to us, shutters were lowered; below, we could hear the screeching of tires from the car park. Our attempt to “participate” in this place failed grandly. Intuitively, we felt that spaces like these, although purportedly open to all, are not public spaces at all. They’re not private spaces, either.

At that time, we weren’t able to precisely explain the fundamental insufficiencies of these spaces and why they don’t contribute to a vibrant city life. Experiences like this sparked my interest in the topic and led to the study of both architectural theory and urban sociology.

Parkbank Europaviertel – © Benjamin Semmler

Sandra: As a graphic designer, I see a strong overlap between my work and architecture, particularly in public spaces. Whether it’s wayfinding, functional inscriptions, amateur graphics, or traditional advertising like neon signs and posters, the visual identity of public spaces is significantly shaped by graphic design. With the increasing commercialisation of public spaces, it’s crucial to question this omnipresent presence critically. I remember the day when a 5-metre-tall advertising column was installed right in the middle of the small but lively square in my neighbourhood.

First, I was a bit shocked by the dimensions. I then noticed other differences to the classic advertising columns we were used to (the so-called Litfaßsäule): The new pillars are backlit, they rotate, and almost exclusively display large-scale commercial ads. The impact of such installations on our perception of the city is enormous – yet the commercialisation of the city is largely taking place outside of public debate and criticism.

On a different note, my interests also include the intersection of architecture and book design, a field I’ve been involved in for several years. Working with Park Books, a Zurich-based publisher focused on architecture and urbanism, has allowed me to explore how specific architectural questions and themes can be translated into the form of a book. It’s not just about the layout; it’s about the materiality and conceptualisation of the book as a three-dimensional object. How can the essence of architecture be captured within the pages and physicality of a book? My interest in exploring the graphic representation of architecture and urbanism also extends to other media, including architecture photography and our online journal.

How would you characterise the city where you live and work? And how does this context influence your work?

Frankfurt is an ideal location to take a critical look at current building and urban planning. The city houses a multitude of functions in a relatively small urban area: it has an international financial district, Europe’s fourth-largest airport, and one of the largest centrally located convention centres. Frankfurt is one of the most socially diverse places in Germany, yet its urban development is extremely fragmented. Over the past twenty years, the city has experienced a construction boom of “Gründerzeit” proportions. The quality of architecture and urban design has taken a back seat during these decades.

Pretty much every urban planning mistake a city can make has been made in Frankfurt. We’ve seen the privatisation of city design in the Europaviertel, a huge residential complex in the city centre, which was developed by two private companies. There’s been a decline in public spaces, which are mostly being planned and used for commercial events, such as Frankfurt’s Roßmarkt, which was deliberately designed as an event space.

Lastly, the political inability to either solve the housing issue nor to pursue a different transport policy outside of model projects. These profound problems contrast with an urban activism that fixates on temporary measures and “creative ideas”. In this sense, Frankfurt provides ample opportunity to examine the pitfalls a city may encounter during rapid growth. This analysis is especially relevant, as the principles of city planning and restructuring have not changed significantly since the 1960s. We aim at a general critique and are, of course, interested in a variety of different cities. Our thesis is that Frankfurt is everywhere. In other cities, like in Berlin for example, you just have to travel further to see similar urban planning failures.

What does your working desk look like?

Never not working — that’s Sandra’s desk on the left and Benjamin’s on the right.

Working Space – © Sandra Doeller / Benjamin Pfeifer

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

We think of architecture as part of public space. Individual buildings communicate with one another; they should relate like good neighbours and (ideally) come together to form functioning public spaces. Architecture and architects don’t merely construct buildings – they build cities. Aesthetically, there should be a balance between individual character and contextual dialogue. This doesn’t mean that innovation and new concepts in urban design and architecture should be avoided, but rather that the ultimate judgment on urban architecture should only be made in its spatial context.

Spatial context means to us to include the building’s practical use. How is the structure used on a daily basis? How does it function in the public spaces it is part of? We thus focus equally on the house in everyday life as well as on the everyday house. And beyond that, at the same time, we consider the social influence of architecture and its impact on social relations and public life.

What was the most important thing you needed to agree on as a group to be able to create this project together?

We summarised our fundamental positions in an exposé – a little manifest, if you will. A synthesised version, presenting our five points of criticism, can be found on our website. Defining our position within the current discourse on urban planning and activism was even more challenging. We observed that the criticism being raised in public debates is often opinionated and subjective, whereas professional criticism tends to be overly technocratic.

This is evident in the debate surrounding Frankfurt’s Europaviertel: Popular criticism has largely focused on the façades along Europaallee, which are described as “monotonous,” “boring,” or even “ugly.” In response, commonplace counterarguments emerge – statements like “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” “the district just needs time,” or “no one is forced to live there.” Such opinion-driven criticism lacks clear criteria that could inform the development of vibrant, urban neighborhoods. While one can argue about the objectivity of criticism, it should strive for measurable standards.

Yet the current zeitgeist favors a “positive” approach, which is expressed in all kinds of temporary model projects and in the idea of urban appropriation. While these initiatives may offer creative impulses, they tend to sideline a more structural and long-term approach of urban development. Many of them risk becoming apolitical by assuming that good intentions and ideas alone are sufficient to achieve better outcomes. This is a classic liberal fallacy.

We believe that only through analysis and critique can meaningful change occur. For example, we need to understand the fundamental principles underlying urban planning processes and to what extent these processes are shaped by the legal and economic framework. We also need to understand how much urban development is determined by private and commercial interests, and we need to show architectural design’s social impact. With our platform we aim to contribute to the architectural discourse in a way that provides a foundation for political decision-making in the urban context.

Name your favourite…

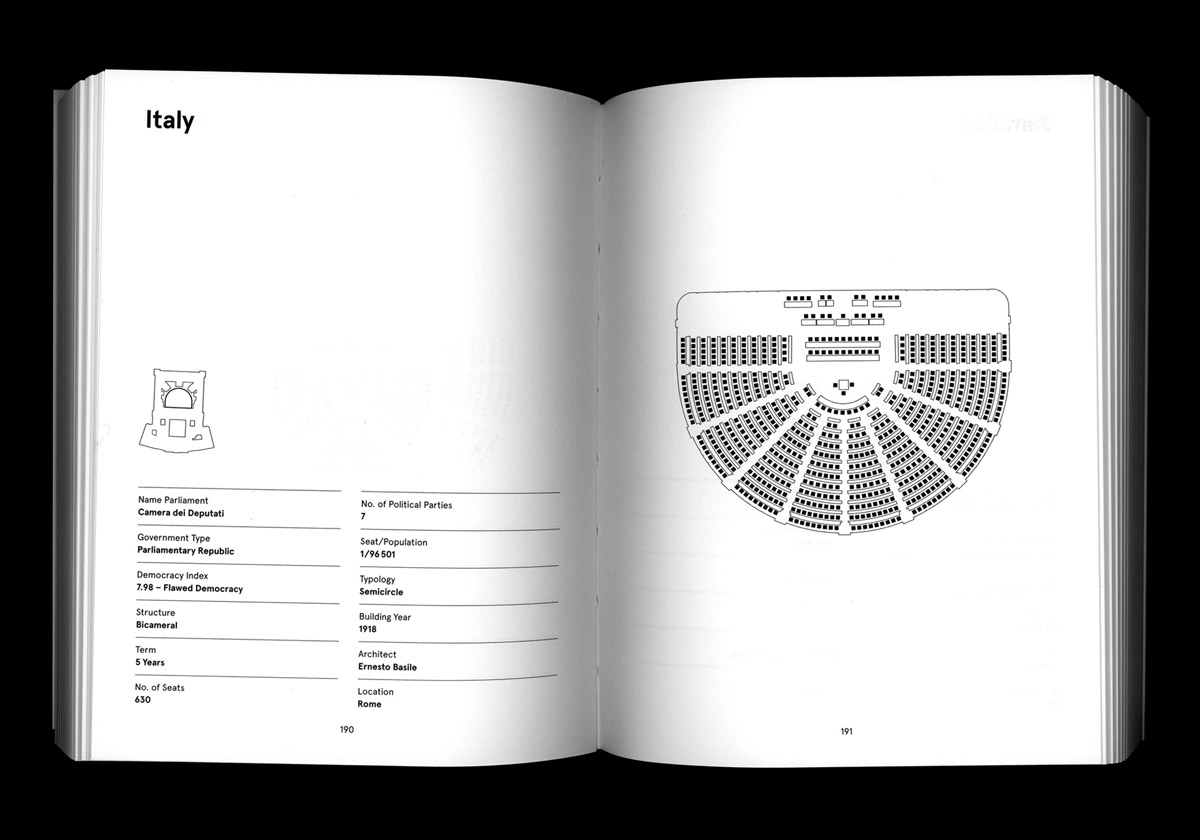

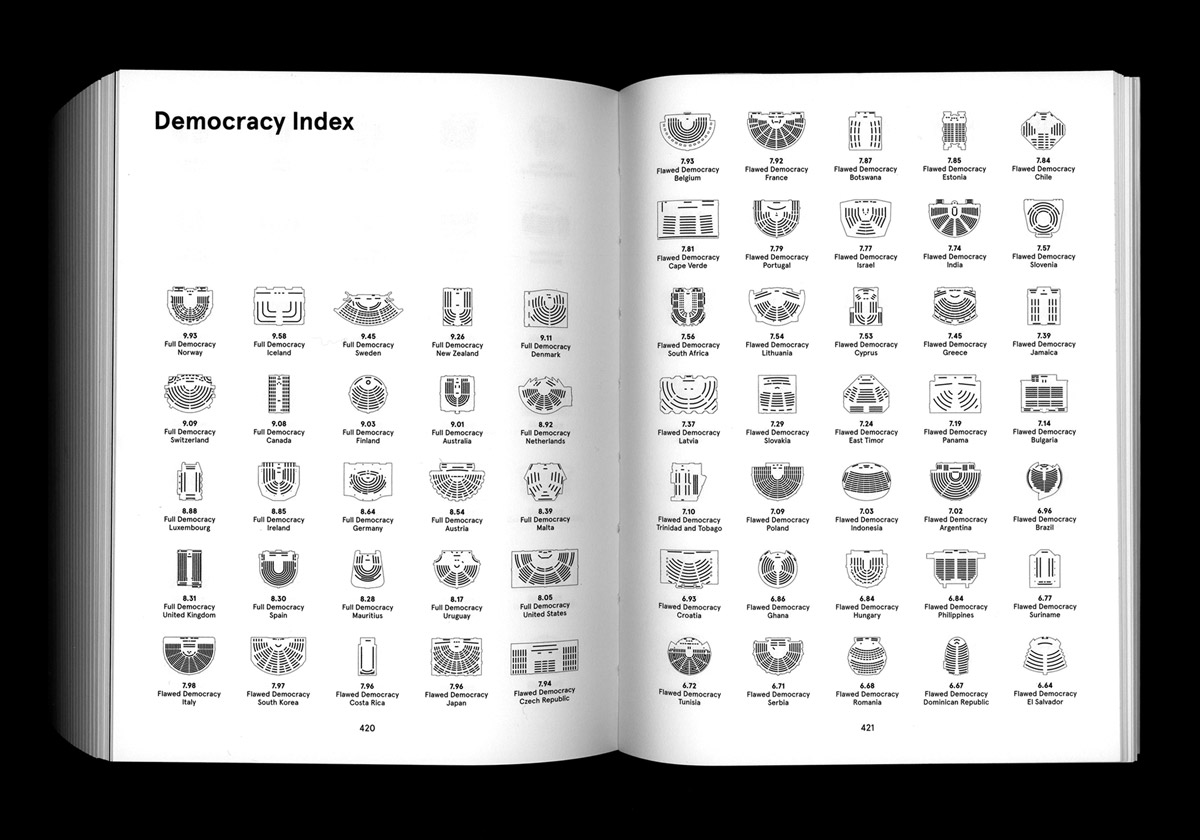

Book/Sandra: I just got my hands on “Parliament”, a fantastic book that explores the intersection of architecture and politics. It’s based on research into the architecture of spaces of political congregations and was published by the architecture office XML in 2016. The book documents and compares the plenary halls of all 193 United Nations member states, presented consistently in the same style and scale, along with key data to create a comprehensive archive. As the authors put it: “Parliament is the space where politics literally takes shape. Here, collected decisions take form in a specific setting, where relationships between political actors are organised through architecture. The architecture of spaces of political congregation is not only an abstract of political culture, it also shapes this culture.”

Person/Benjamin: My favourite person, as you might have guessed by now, is Jane Jacobs. She has brought basic theoretical concepts such as functional mixing, social mixture, and the necessity of architectures from different historical phases into urban planning. In her book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, she formulated a necessary and overdue critique of modern urban planning – one that feels almost prophetic when considering today’s new developments and urban renewal projects. We can learn from Jane Jacobs that a complex, diverse city life has very clear planning and architectural conditions. These conditions need to be restored today.

How do you communicate architecture?

We are an online journal. The articles on our website contribute to the discourse, and we dedicate a lot of room to the visual exploration of the urban space, juxtaposing classical architectural photography with images that demonstrate how buildings and urban spaces are perceived by passers-by. Our website offers broad and inclusive access. As a dynamic medium, it can evolve over time to take on an archival character. We are active on social media as well, though we strive to be independent from the constraints of algorithms and their constantly changing preferences.

What are your thoughts on architecture and politics?

Architecture is political. Who would disagree? And indeed, from the climate crisis and the housing shortage to liveable neighbourhoods with public spaces, all these areas are, to some extent, connected to architectural planning. Yet architects rarely determine the programs of the buildings they design – but clients and investors do. Architects do not shape the frameworks for social housing either; that’s up to politicians. While architects can influence the selection of climate-friendly building materials, the greater responsibility by far lies with the building materials industry. Still, every architect’s choices shape the built environment and its social and ecological impact.

So, what does “architecture is political” actually mean? First, we shouldn’t confuse “political” with “socially influential”. In recent years, the “p” word has been thrown around quite a lot. From our perspective, something is political when the actions have a claim to be generally binding. Actions that, in one form or another, are connected to procedures and decision-making processes or at least aim at them. The climate movement, for example, aims for effective (generally binding) climate protection measures, while feminism strives for equal rights and material equality. In this sense, we can also understand certain issues as political, namely when social controversies form around them. What is considered political can also change over time. For instance, it’s been a long time since marriage between Catholics and Protestants was a political issue. Today, how we heat our homes or how we organise traffic are very much political matters.

What does this mean for architecture or design? Without question, architecture has strong social impacts. However, it only becomes political when there is a general debate – a broader argument about the role it plays and the impact it has. Buildings and architectural design are therefore not inherently political, as they aren’t part of a political decision-making process aimed at creating binding policy. Rather, architecture has a social impact – one that is far too often dramatically underestimated. For this reason, architectural design should be given more attention in the political realm. We observe a reversal of the relationship between architecture and politics that has a certain irony: The more politics withdraws from urban design, the louder we hear phrases like “architecture is political” and “design is political”. This reflects a broader neoliberal trend: the shift of political responsibility from institutions to individuals.

Finally, we believe architects should recognise that architecture is embedded in specific social and economic structures—but it is not able to create them. The politically-minded architect is, in the end, a professionally informed citizen. So rather than overstating the responsibility of their profession, architects should get involved in public debates and, why not, in political organisations.

How do you understand the relationship between theory and practice in architecture?

We believe that theory is the basis of any practice. Architectural theory is important not only because it offers a comparative view of solutions over time – such as through architectural history – but also because it fosters reflection on architecture and its underlying principles. The delineation of architecture from its neighbouring disciplines (art, science, technology, and design) is particularly relevant today; the field is in danger of losing itself as it gets caught up in highly technical solutions (active houses), the rationalism of the property sector (new-build districts), and a certain type of superficial star architecture.

There’s also a lot of pressure to produce pragmatic rather than theory-based solutions. In the age of “small narratives” (Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, 1979), we observe a general, postmodern distrust of overarching theories of the city or architecture, both in current social debates and in architecture itself. Overarching theoretical frameworks are being replaced by an “anything goes” approach to urban and architectural planning, which fails to establish design or planning standards – for example, in relation to purely economically oriented investments. In view of current developments in urban planning and architecture, however, these standards are absolutely necessary, as is a revival of an interdisciplinary, aesthetic, and socio-political theory of the city.

Do you have any recommendations for young architects studying in the field right now? Any activities or fields of study to focus on?

Two activities come to mind: The attentive observation of everyday urban life and, building on this, an in-depth study of urban design theory. Jane Jacobs beautifully described this juxtaposition of observation and theory in her 1961 book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”: “The scenes that illustrate this book are all about us. For illustrations, please look closely at real cities. While you are looking, you might as well also listen, linger and think about what you see.”

Project 1

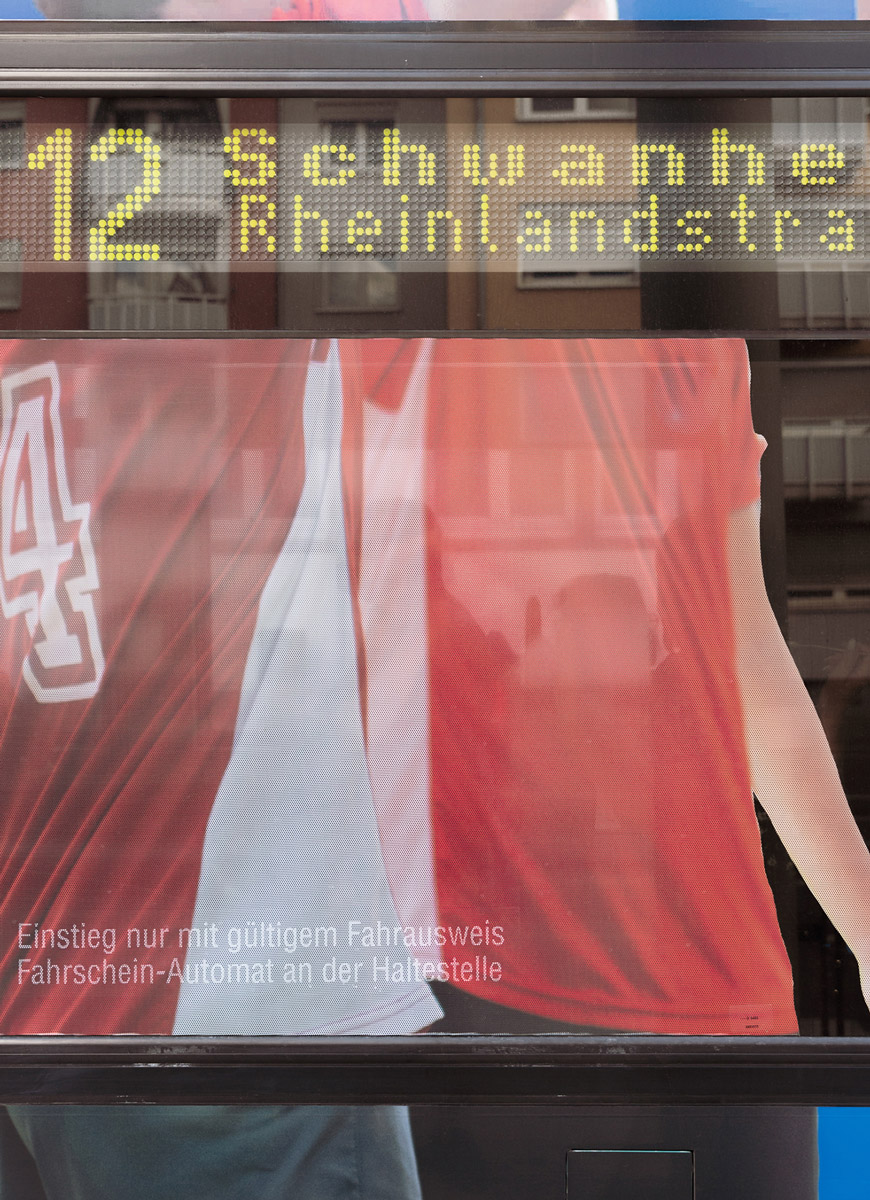

City and Commerce: The Branded Tram

From the series: Elements of the Anti-Urban City

Frankfurt am Main, 2023.

In cities like Frankfurt am Main, trams — once vital components of urban identity — are increasingly overlaid with full-scale advertising. This shift reflects the growing commodification of public infrastructure, where the aesthetic and symbolic value of transport as a civic element is eclipsed by commercial interests.

In the past, vehicles like Lisbon’s streetcars or London’s Routemasters served as visual anchors of collective memory. Today, branded trams, like those in Frankfurt, fragment this potential, subordinating urban coherence to the logic of visibility and market reach.

Beyond visual disruption, this trend marks a deeper erosion: as public goods are privatized for revenue, the city’s capacity for shared identification diminishes. In the long term, the commercial exploitation of public space weakens its democratic and cultural function.

Photos: Sven Kirschenbauer

Project 1

City and Commerce: The Branded Tram – From the series: Elements of the Anti-Urban City

Frankfurt am Main, 2023.

In cities like Frankfurt am Main, trams — once vital components of urban identity — are increasingly overlaid with full-scale advertising. This shift reflects the growing commodification of public infrastructure, where the aesthetic and symbolic value of transport as a civic element is eclipsed by commercial interests.

In the past, vehicles like Lisbon’s streetcars or London’s Routemasters served as visual anchors of collective memory. Today, branded trams, like those in Frankfurt, fragment this potential, subordinating urban coherence to the logic of visibility and market reach.

Beyond visual disruption, this trend marks a deeper erosion: as public goods are privatized for revenue, the city’s capacity for shared identification diminishes. In the long term, the commercial exploitation of public space weakens its democratic and cultural function.

Photos: Sven Kirschenbauer

Project 2

Tour of Idsteiner Strasse

From the series: Endstation Europaviertel

Frankfurt am Main, 2012

In new-build districts like Frankfurt's Europaviertel, the promise of vibrant urban life is often disappointed at the level of everyday experience. This series from 2012 captures Idsteiner Strasse at an early stage of development, revealing patterns that have since become emblematic of many contemporary neighbourhoods.

Public spaces lack qualities that invite lingering; instead, they are marked by neglected outdoor areas, rubbish bins in front of residences and across common grounds, and exposed underground car park entrances that fracture the streetscape. Ground-floor flats retreat behind barriers of isolation, while playground equipment — intended as gestures toward community — stands deserted.

Beyond their superficial flaws, these urban fragments point to a deeper malaise: the erosion of public life as spaces meant for interaction are hollowed out by utilitarian expediency and disjointed planning. The long-term consequence is a built environment that struggles to foster social cohesion or a meaningful sense of place

Photos: Benjamin Semmler

Europaviertel

Website: frankfurtbabylon.de

Instagram: @frankfurtbabylon

Photo Credits: © Frankfurt Babylon

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 05/2025