25/003

Studio Załuska

Architecture Studio

Łódź / Zurich

«The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities.»

«The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities.»

«The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities.»

«The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities.»

«The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

We are two brothers who design and envision spaces. After studying in Switzerland and gaining years of experience in various offices, we founded our own practice, specializing in architecture, architectural imagery and education – we run Studio Załuska (architecture), Robin Archive (architectural imagery) and „What is a house for” series (education). We operate internationally, with our main presence between Poland and Switzerland.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time learning about architecture?

In the 1990s, our hometown of Łódź was in the depths of economic and cultural decline—a complete mess. Once a thriving center of textile industry, built on the hard work of 19th-century immigrants, it crumbled just as we were growing up. We were raised in the art high school where our father was the principal. Every week, we took part in painting, sculpting, and printmaking classes alongside older students who dreamed of attending the Academy of Arts or the renowned Łódź Film School—by the way, ranked recently among the world's top 15 film schools by The Hollywood Reporter.

The themes of vision, craftsmanship, and storytelling were ever-present in our daily lives, starkly contrasting with the indolent and rough reality outside. This contrast shaped our perspective, instilling in us a transformative spirit—the belief that everything we see carries the potential for change, reinvention, or substitution. In these early days, we believe we subconsciously developed our approach to architecture.

Recognizing that solving large-scale problems seemed impossible and that efforts in this direction might be futile, we felt architecture should possess its own autonomous conceptual value, not merely rely on its interaction with the context. In chaotic environments, the only way to rise above mediocrity is to become a pearl in the mud—namely, in architectural terms, adhering strictly to self-imposed and invented set of principles.

What are your experiences founding your own office and being self-employed?

There’s no better way to understand reality than by throwing your own imagination at it and seeing what unfolds. We started our practice primarily to engage more deeply with the real world, to see and experience more. Being self-employed is an adventure. We’re still at the very beginning of our journey, building our first structures.

The most fascinating part is the constant uncertainty—almost every week brings a new crossroads, forcing us to choose a direction with no guarantees. It’s challenging and tough, yet somehow it feels more natural. Brutal and beautiful at the same time. We believe the most important challenge is deciding what to engage in and what to let go. In the early stages, there are countless distractions, making it easy to lose focus or stray off course. Sometimes, the key to success lies in deliberately avoiding certain activities, so you can concentrate on the ones that truly matter.

How do you remember your time as architectural employee/worker?

Our experience has shown that working as an employee often limits exposure to the full complexity of an architectural project—the very aspect that makes the field so fascinating. For us, architecture isn’t just about designing buildings; it’s about uncovering the deeper forces and mechanisms that shape interactions between people, institutions, and the built environment. As an employee, you operate within a protected space.

As an entrepreneur, you are fully exposed, feeling every impact firsthand—jumping without a parachute. The ability to take action, test ideas, fail, and problem-solve at every stage is fundamental to our approach. We don’t see this as an obstacle but as an essential part of the design process itself. Since starting our practice, our lives have completely transformed. We’ve traveled to different places, met countless people, and immersed ourselves in a wide range of experiences.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

Łódź is a city in the midst of rapid and intense transformation after decades of stagnation. The air carries the scent of renewal—hope mixed with the faint anxiety of over-investment. It’s a place caught between its industrial past and an uncertain, ambitious future, where faded factories give way to glass facades and new ideas struggle to take root in old soil. We find its atmosphere deeply inspiring—the raw energy of change, the tension between nostalgia and progress. Yet, for now, our work takes us elsewhere. We are a traveling office, kind of strangers in our hometown.

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

Working Space – Studio Zaluska

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

The essence of architecture lies in creating spaces that engage both physically and intellectually. To truly feel at ease in a space, one must have the opportunity to question, analyze, and grasp the underlying logic and ordering system of a building. Without this quality there is nothing to bring one step forward, or question, or have a discussion about. It’s a finite, at best pleasant, but dull reality. Architecture exists at the intersection of structured principles and the spontaneity, causality, and the disorder of everyday life.

Name your favorite…

Book/Magazine: Designed future - Mendes da Rocha

Building: House on a curved road - Kazuo Shinohara

Mentor/Architect: Giacomo Guidotti and Silvia Gmür- first real teachers

Building material: Concrete

Spatial Memory: Cimitero di San Michele - Venezia

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

We find it difficult to offer universal formulas. Our utopia is not a singular vision but a richly layered reality—one where strong, even conflicting perspectives coexist, sparking discussion, exploration, and the freedom to change one’s mind. It is a world filled with opportunities to be challenged by ideas, engage in open dialogue, and question assumptions. We aspire to a life of constant discovery, where every visit to a friend’s home or every walk through the city reveals something new. For us, the greatest threats to architecture are trends and ideologies that impose uniformity, reducing it to a set of rigid dogmas rather than a living, evolving discipline.

Paradoxically, to make this utopia possible, we believe in holding a firm position—a declaration of qualities or themes that we choose to explore in every project. The most meaningful discussions emerge not when there is a universal standard of what is good or bad, but when individual actors passionately advocate for distinct, well-defined visions. In our view, architecture thrives on substantive, diverse perspectives rather than a harmonious yet diluted cultural consensus.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

We believe the most important factor is education. Architecture cannot be treated as a profession akin to what is commonly understood as sustainable work—at least not in the near future. Fundamentally, architecture is, and will always be, a battle. There are too many conflicting interests involved whenever something is built, which is why we need architects with the mindset of warriors or pioneers. As a society, we need not only well-crafted creations but also provocation and risk. These elements generate friction.

Young architects may think it’s possible to propose unconventional ideas without having to fight for them—but that will never be the case. We believe that if students were properly warned early on that this profession is, in a sense, dangerous—much like public service or any other demanding field—the profession would be a more fulfilling and honest place. The most sustainable situations in life occur when there is little or no gap between expectations and reality. Once this issue is addressed at the educational level, the focus can shift to the finer details. We believe this should be the starting point.

Regarding buildings themselves, we find it limiting to reduce sustainability solely to the carbon footprint of materials, reuse potential, or the waste generated at the end of a building’s life cycle. The most sustainable buildings are the ones people love and take care of—and this is driven by ideas, typologies, light, and other immaterial parameters. We must not forget the central role these factors play in the future discussions on sustainability, so as not to be misled by purely quantity-oriented calculations.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? (What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?)

Hand drawing and cutting with scissors—these may seem like simple, almost archaic tools, but they represent the fastest way to bring big-picture ideas to life. The tactile nature of these activities allows us to make immediate, intuitive decisions about form, composition, and structure, often revealing the most essential aspects of a concept in a matter of moments.

These methods bypass the complexity of digital tools, enabling us to engage directly with the materiality of our ideas. However, before diving into creating, it is crucial to first ground oneself in a deeper understanding of the world. This requires more than just technical skill—it demands reflection and introspection. Reading philosophy books and travelling on foot—these activities are not mere pastimes but formative experiences that shape our worldview. This slow, deliberate exploration gives us the space to reflect on what kind of life we want to propose to others.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

We combine hand drawing with photorealistic renderings to visualize our ideas. We believe that hand drawing in scale is the most efficient and intuitive way to translate ideas onto paper. However, it’s equally exciting to see these ideas come to life in sharp, defined images, with light and materials—sometimes even pushed to the point of over-definition.

These two extremes create a tension that we find stimulating, providing a clear and comprehensive view of our direction. We consider it essential to use realistic imagery and simulations not as final representations of a completed project, but as tools for exploration and study—helping us find the right spatial solutions. Once everything is clear at the conceptual level, we focus on drawing the technical plans, ensuring they are executed with precision and care.

Do you think AI is changing the field of architecture?

AI is transforming the field of architecture by enabling us to imagine and explore ideas more quickly. However, despite popular perceptions, the essence of the architectural profession goes beyond generating and communicating bold ideas. In practice, much of the work involves negotiating, supporting clients, finding a balance between market demands and investor interests, and leading teams.

The most compelling architectural ideas often don’t stem from references but from real-life experiences applied to unpredictable opportunities. Quality architecture emerges from a multitude of practical, hands-on, human activities—many of which are difficult to replace or automate. If architecture were only about creating images, AI might soon take over. But if it is about serving people, developing long-term strategies, and managing materials for specific purposes, architects will remain indispensable. In this context, AI will likely play a vital role as a supportive tool.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

For us, it’s essential to continually revisit the critical analysis of the past and draw inspiration from well-designed, beautiful, and inspiring spaces. This is why, a few years ago, together with our friends Riccardo Amarri, Matthew Bailey, Kou Matsumura, Keigo Mori and Jie Zhang we launched the website whatisahousefor.com.

It is a collection of writings exploring the qualities of domestic space. To date, we’ve conducted over 50 conversations with prominent architects and thinkers we find particularly inspiring, and we highly recommend reading them, as they delve into the core of creating spaces for everyday life. We continue to publish these discussions on the website and Instagram, and we’re currently working on a book to further expand on these ideas.

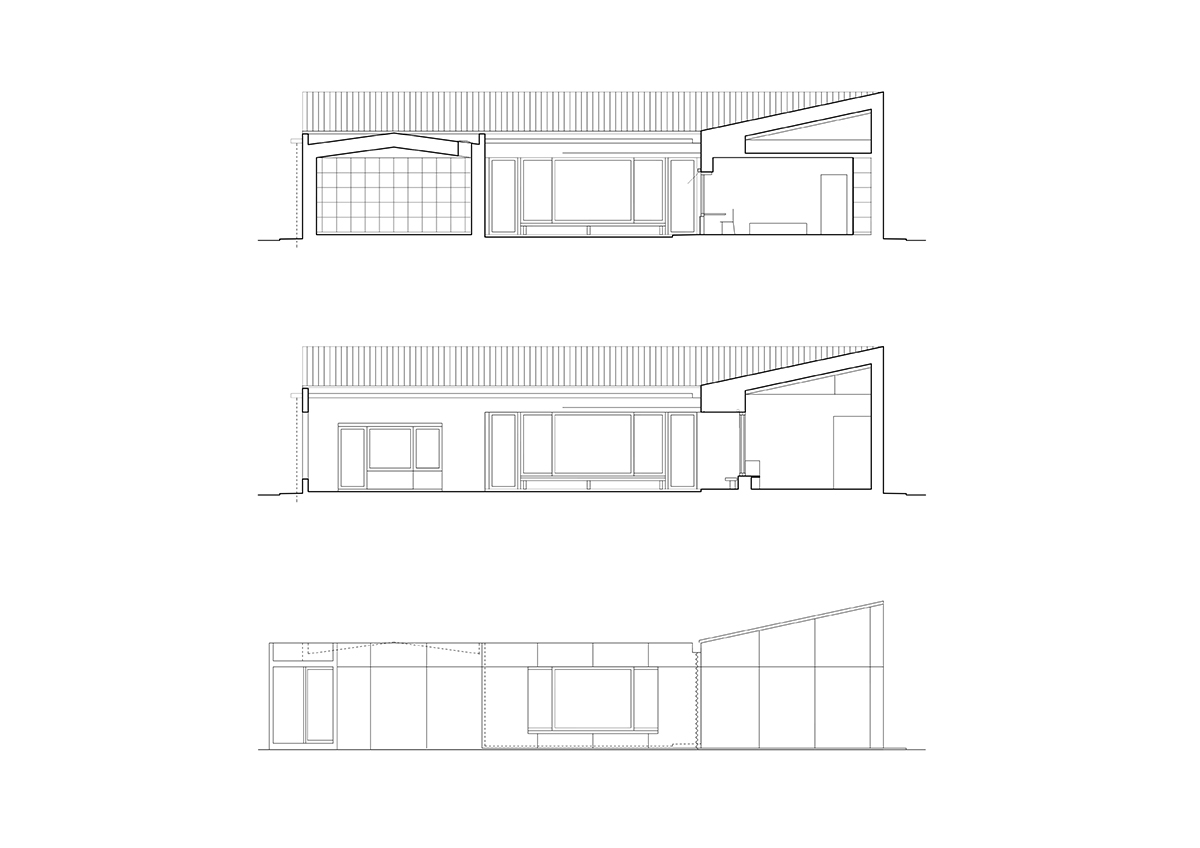

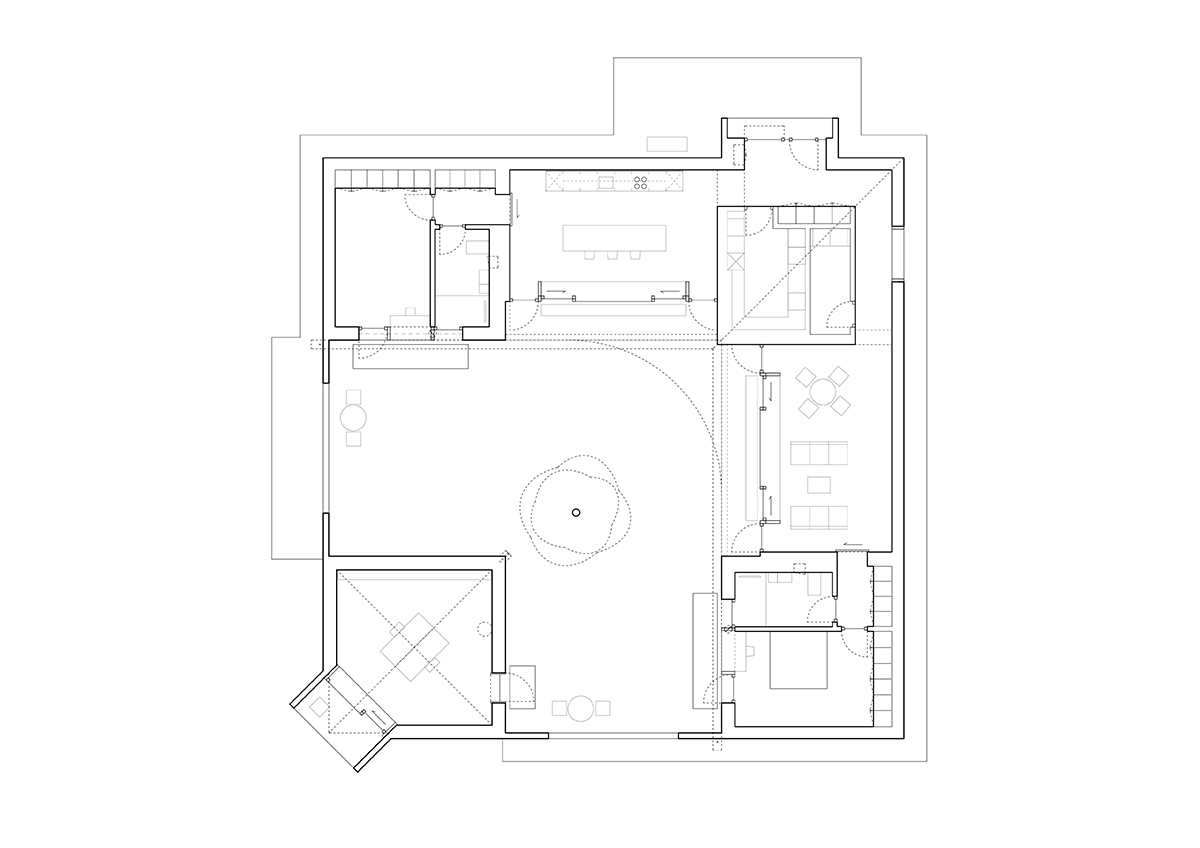

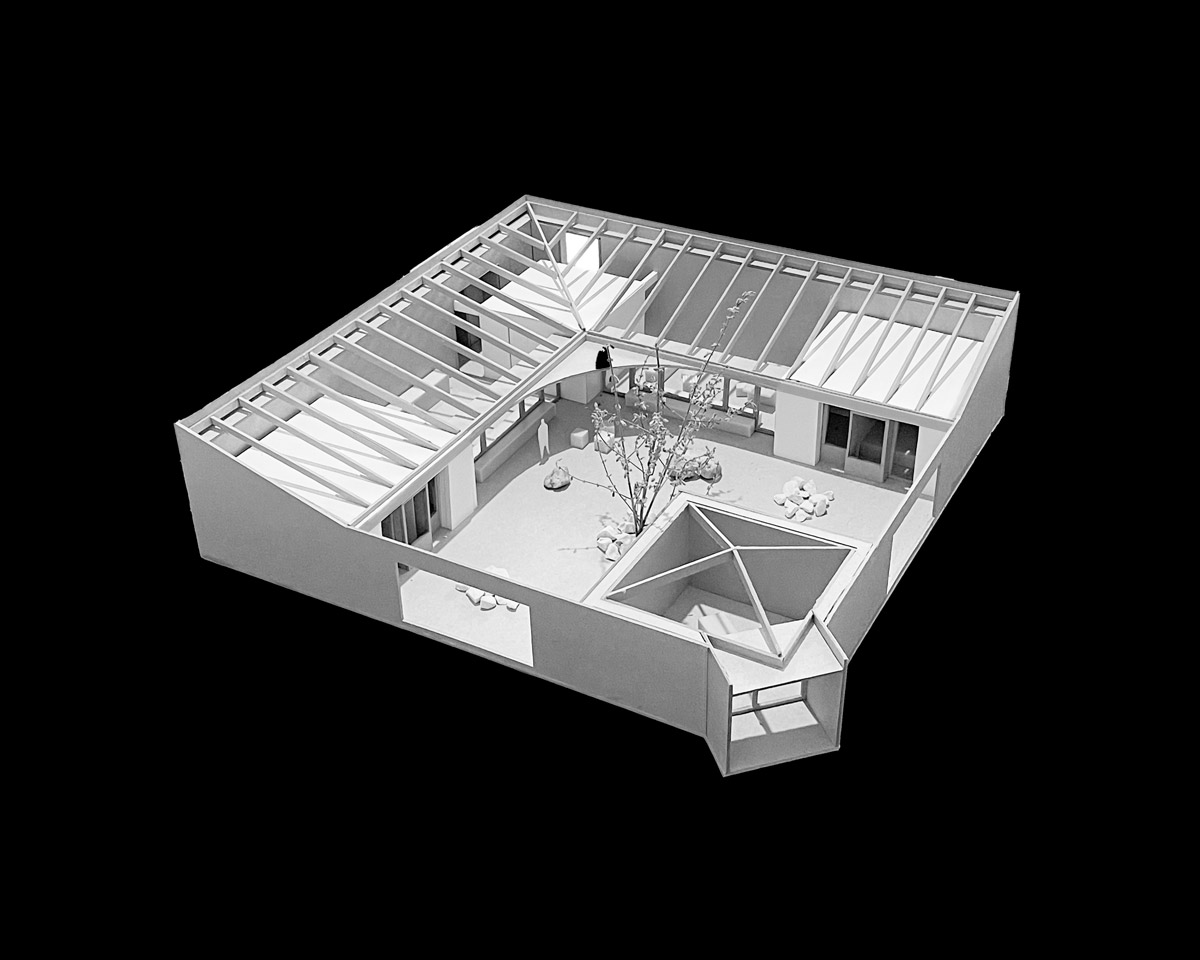

Project

House near

Warsaw

We are currently working on a private residence near Warsaw, designed around an L-shaped atrium. The two main and expansive areas of the house—the kitchen and living room—are fully open to the atrium, creating a seamless connection to the outdoor space. These areas form a cross-shaped layout, with a long axis extending through two large openings in the concrete walls, providing a striking sense of depth and perspective. The remaining spaces, including the bedrooms, technical rooms, and study, are housed in boxes at the corners of the building. These rooms open to more intimate, informal sections of the garden, offering a sense of privacy and tranquility.

Website: studiozaluska.com, robinarchive.com, whatisahousefor.com

Instagram: @studio_zaluska, @robin_image_archive, @what.is.a.house.for

Photo Credits: © All images and photos made by Studio Załuska

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 04/2025