22/022

B-ILD Architects

Architecture Office

Brussels

«Sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.»

«Sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.»

«Sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.»

«Sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.»

«Sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

My name is Kelly Hendriks, I was born in Belgium and I am currently living and working in Brussels. I founded B-ILD in 2009 together with architect Bruno Despierre. B-ILD is located right by the canal in Brussels – the city we consider to be our hometown. The team has organically grown from two people back in 2009 to nine people in 2022. During this time, we focused intensely on creating a resilient office structure with two main focal points: building qualitative buildings and managing a positive working environment for our collaborators.

The portfolio of B-ILD is very diverse in scale and program with an emphasis on public projects. Several of the assignments were awarded to the office through competition procedures such as the Open Call by the Vlaams Bouwmeester, the Call by the Brussels Bouwmeester and Oproep Winvorm. B-ILD chooses to elaborate on projects which create an added value to neighbourhoods and society.

B-ILD is Kelly Hendriks, Bruno Despierre, Stephanie Vander Goten, Raf Geysen, Matisse Hautcoeur, Joris Kerremans, Marta Gruca, Loïc de Béthune, and Birgitt Use.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time studying/learning about architecture?

I’ve always tried to keep an open mind during my studies. The idea of studying at the same university for five years in a row scared me as I wanted to learn from different contexts and people as much as I could. So I ended up studying in different universities trying to compose my own program of interests, from Ghent to Eindhoven, to Fukuoka and Tokyo in Japan, and finally in Barcelona. I look back to those years as a solo trajectory that taught me an awareness of the complexity of architecture and the importance of process. I really believe in the idea of decentral learning, to create one’s individual understanding. It is something I still do to this day and I also urge my students and collaborators to do so. Think outside of the box and to go beyond the obvious, to focus more on the process than the end result.

What are your experiences founding your own office?

After working a few years at established architecture offices such as Christian Kieckens, 51N4E and for a short time at OMA New York, I wanted to start my own practice where I could be author of a process rather than the architectural object. I couldn’t and didn’t want to claim the classic form of authorship in architecture. Therefore, realizing my own projects wasn’t necessarily my main incentive, I was more interested in setting up the mechanisms to create architecture.

It took some time to find the right balance, but we did it. At B-ILD the collaborators are mainly in charge of designing and following up construction. Bruno is the office manager and I supervise all projects. To protect the financial feasibility of a project, we thought of some rules to follow: we don’t design complex details, we follow basic standard connections; when starting a new project we introduce a maximum of one new material or construction technique that we haven’t already worked with, allowing enough time to research on this aspect. A rational, clear and economic design follows, and leads to a building that we know how to build, even without a virtuoso contractor. This is the reality in which I want to work as an architect and my collaborators know this. I believe it is also why our work is coherent and recognizable.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your projects? What meaning does location have to you overall?

We are located in Brussels, quite literally the central point of Belgium. In Belgium, and especially in Brussels, language is an important factor for architectural practices. There is generally a clear line between architecture from Dutch speaking Flanders and French speaking Wallonia with little cross pollination in between. They both mainly work in their own territories where competitions are organized by local regions and governments in either Dutch or French, ultimately also leading to a different architectural language. In Brussels things are different however, here both Dutch and French speaking offices have to work within the same framework, on the same competitions, sometimes as competitors, other times as collaborators. For us, this was a specific reason why we chose Brussels as our hometown and it remains a strong incentive for us. We take this opportunity to operate in the whole country (Belgium is of course very small) and have projects in Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels.

‘Location’ is also a very important topic for me personally. Growing up in Limburg, I was always fascinated with the coal mines in the region. Though they were not active anymore, they left behind strange artificial landscapes. At places, mounds composed of dug up stone and ground created isolated hills (called terrils) against the flat backdrop of the typical Flemish landscape. In other places, former mine sites were planted with conifer trees in a strict orthogonal planting schemes. I guess these early impressions and confrontations with a clash between artificial and natural have later on shaped and influenced my architectural work in an important way. Last year I have also taught a design studio dealing with these specific artificial landscapes.

Artificial Landscapes | Student Work | Archive Photograph of a coal mine

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

Three years ago, we moved into our new office space. We found a mid-rise building from the 60’s literally a stone’s throw away from our previous place. The building was one of the first examples of hybrid buildings in the city, with four layers of office floors in the lower part, and four residential floors on top. As to today, it still functions as such. We share the top office floor, where we have a nice view on the city, with another architecture office, a rendering agency, an engineering firm and graphic designers.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally/for you as a studio?

Two things: social relevance, and impact on the future. I believe that architecture should be socially relevant. Therefore, our work mainly consists of buildings for youth care, schools and community centers. Of course we also work on other buildings, but it is in these projects that I find most fulfilment in my profession. I enjoy working with the client, private or public, and the users, trying to understand their needs to cocreate a functional program that works within their financial capacities.

I want to make architecture that has impact on the future. As architects in these times, we can’t deny the negative impact building, almost by definition, has on our natural environment. However, it is also still necessary to build. So we always approach a new project with a conscious rethinking of the question: is it necessary to demolish and build new? What can be reused or renovated? Is this location actually good? How can we limit the environmental impact? … For me, sustainability doesn’t only come in the application of energy efficient techniques based on renewable sources but starts already with the first design intentions.

Name your favorite…

Book/Magazine: The Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner. It is an interesting book for architecture students to learn about references and concepts.

Building: The FRAC in Dunkerque by Lacaton & Vassal

Mentor/Architect: Christian Kieckens

Building material: Brick

Spatial Memory: My super tiny apartment in Tokyo that taught me the necessity to think in multifunctional ways.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

I hope for more collaboration between all parties connected to the architectural process on a large scale. This will be the only way that we as architects can make a true impact on climate change. There are already good initiatives dealing with CO2-neutral and energy efficient neighborhoods today, but that’s not enough. We will all have to work together and learn from each other. We have to take more collective responsibility, instead of all for profit we need profit for all. Only then, I think, we can come up with feasible and realistic ways to make a positive change, one where one’s losses are another’s gains. I see a young generation coming that is conscious and enthusiastic, so I am hopeful.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Go to the library. There is so much knowledge and so many surprising references waiting for you that are not preselected by any algorithm feeding you always the same things. Create your own story.

Last year, on the first day of university, we took the students for a whole day workshop in the library, forcing them to look in depth for references instead of launching a google search. References found on the internet were forbidden, they had to come from books, magazines, newspapers, etc. At the end, we found that students, whenever they were stuck with their design, found a space of inspiration and calmness in the library. Already just the act of going to the library helped them in their process.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

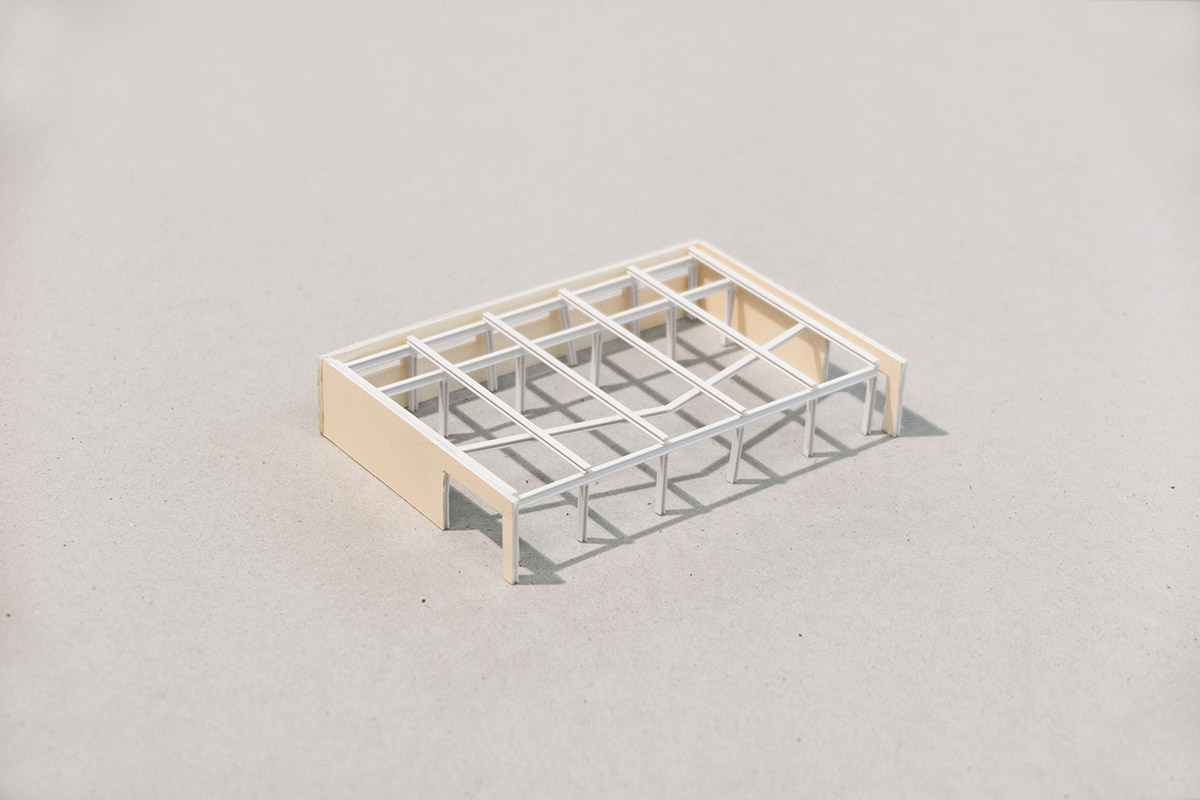

Definitely the physical model, not only as a way of representation but mainly because it forces you to work together, to sit around it and to try different things over and over again.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

BC Architects and BC Materials. They are a young architecture office from Brussels that is setting up their own production of sustainable building materials based on earth, sourced and made in Brussels. They use earth extracted from large building sites in Brussels to make certified construction materials such as bricks, plaster and rammed earth floors. The concept is simple, yet so renewing as well.

Project 1

Warot Building

Herent

2020

Warot is the latest addition to the public facilities of the village of Winksele. It hosts a wide range of activities in a carefully designed multifunctional hall and adds a new soft link to the village’s urban tissue by opening up the surrounding fields for play. The project embraces its messy rural context and elevates it through subtle design choices.

Warot is situated near an existing sports campus in a village in the Belgian countryside. The intervention is made up of a new building and a playing field, separated by a brook which is now crossed by a new bridge designed by UTIL. The bridge is positioned in such a way as to create a new, soft connection between the existing sports facilities and the local school, childcare and youth center, developing a new soft axis that connects the town’s public spaces and facilities.

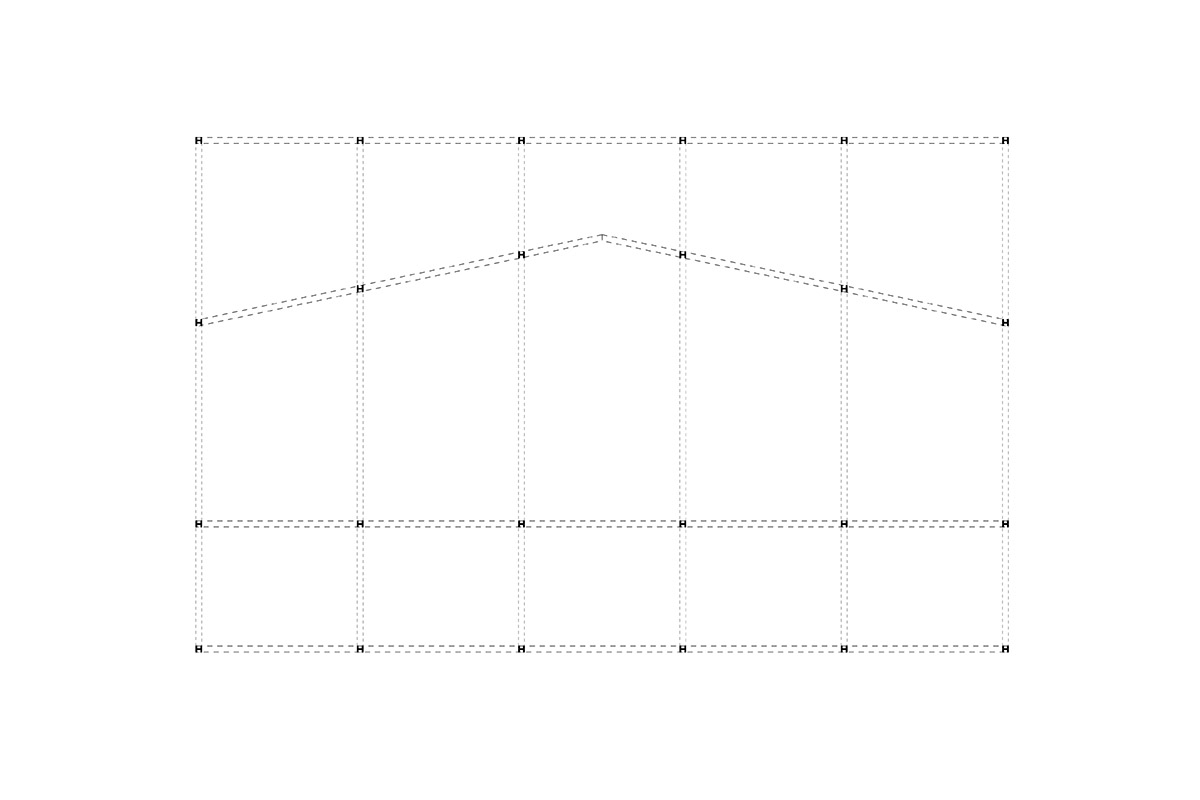

The new building serves as the polyvalent catalyst of this axis and is designed as a space for a variety of activities ranging from children’s activities, card games to yoga classes. A low volume with a simple, symmetrical floor plan offers a base for these activities and serves as a backdrop for the playing field. A large bay window with a single fold emphasises the new connection with the village and offers it a welcoming facade.

This project aims to achieve a truly sustainable impact on the community for the long term. This implied increasing the complexity of the task by involving as many local actors as possible and seeking to do the most with the limited means available.

“More space for less budget” became the priority; it was decided to strategically invest the available funds where most impact would be had: in the spatiality, adaptability and the structure.

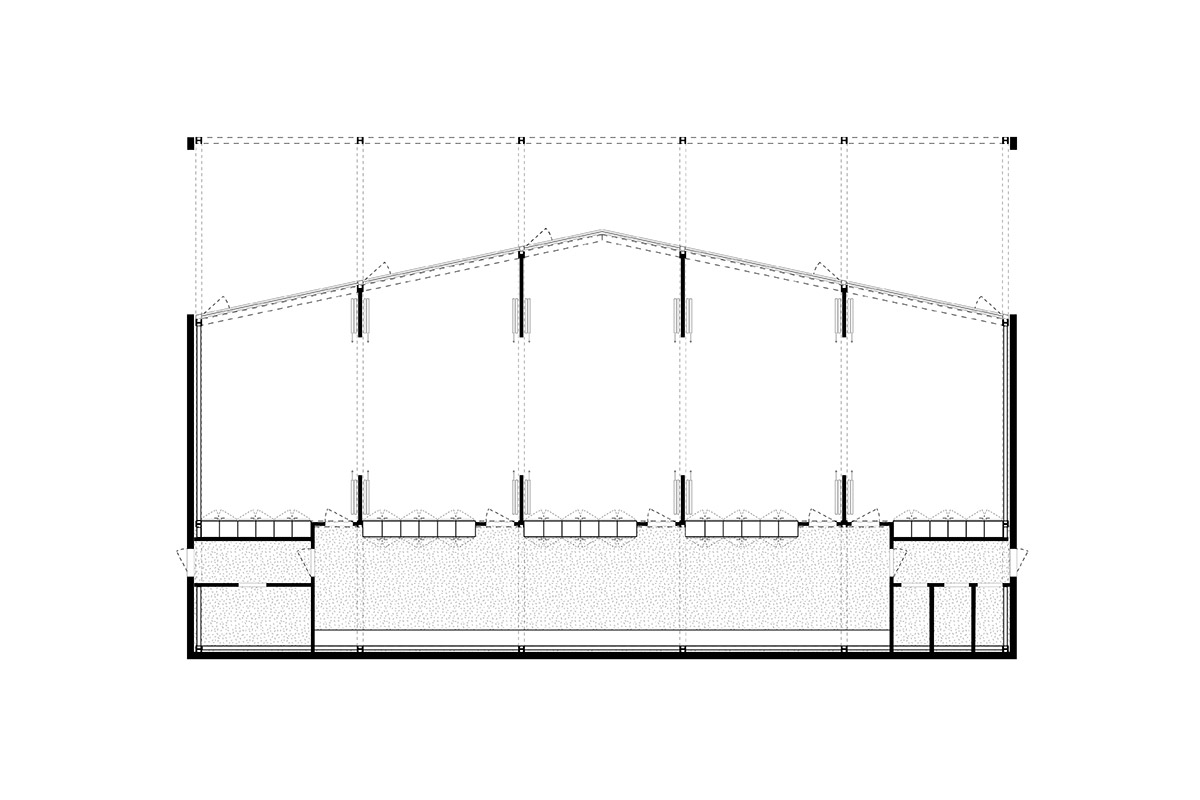

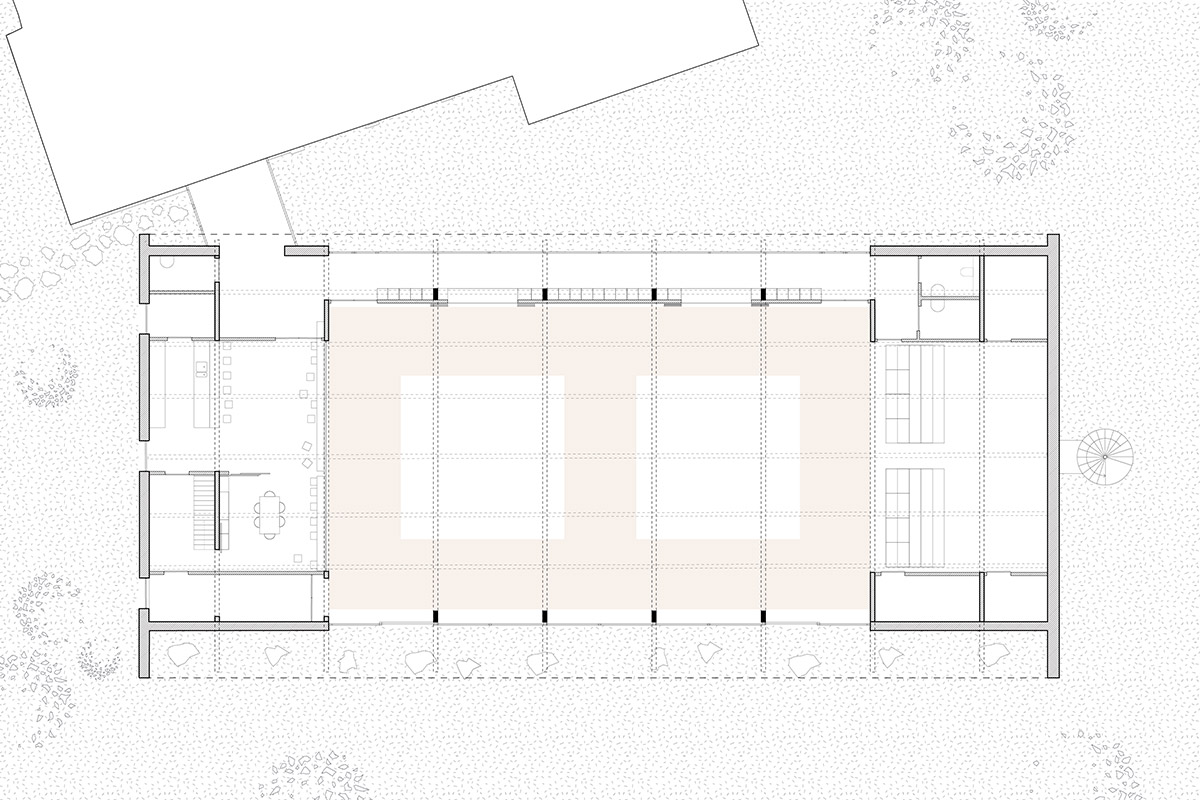

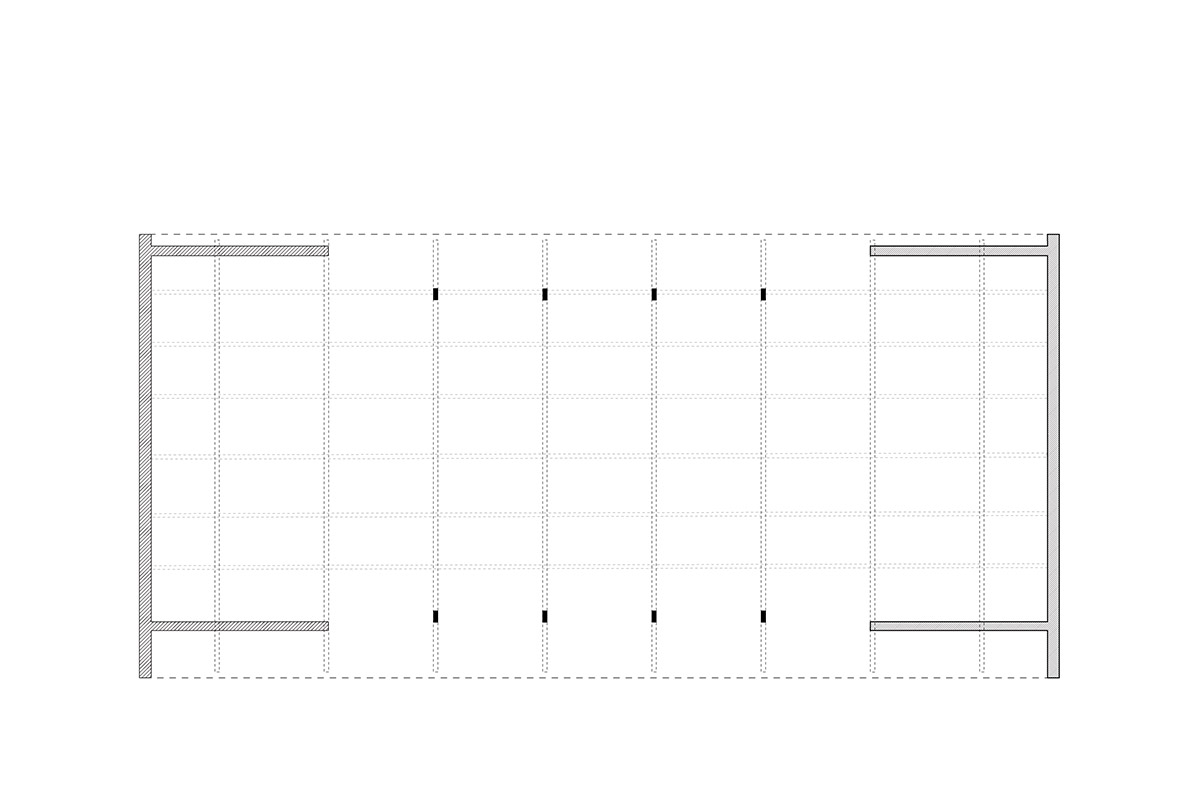

The building’s plan follows a structure of six parallel beams, generating spaces that can be interconnected or partitioned through the use of folding walls. These rooms are serviced by a wide corridor that serves as a backstage and hosts circulation, storage, and technical zones. A wide glazed bay faces the playing field across the brook, its sliding doors opening up to a covered outside space that form an extension of the interior space.

With these few tools, the multipurpose hall offers the village an open infrastructure where partitions can be moved and circulations multiplied to accommodate a wide array of activities. This open-endedness has attracted many new unexpected users to the project since it opened (e.g. a COVID-19-facility).

Simplicity of structure and material is a cornerstone of the design. Common materials were chosen for their simplicity, ease of construction, durability and ease of maintenance while assuring a low ecological impact. Sand-colored brick, brown concrete flooring, steel and metal ceilings are brought together through sensitive detailing to elevate their utilitarian nature. This reduced palette of sensible and everyday materials is applied in sensitive ways for both the interior and exterior finishes, adding to the simplicity of the architecture.

The clear and symmetrical plan ensures that the cost of the structure is reduced. The roof structure is made up of steel beams that hold up a steel perforated corrugated sheet. The choice to perforate this structural sheet and keep it exposed ensures the acoustic quality inside the building, while avoiding the cost of expensive acoustic finishing.

Interior walls are made up of non-loadbearing partitions and movable walls, assuring future adaptability as the village’s needs evolve. This emphasis on adaptability makes the project truly sustainable, assuring the building will remain meaningful for generations to come.

Project 2

Sports & Community Building

Kortemark

2020

By carefully attaching the new sports building for a local judo club in Kortemark to its neighboring community center building, it presents an opportunity for the club as well as the community. It thus also offers new perspectives for the rest of the sports site and the municipality of Kortemark. By creating a new beacon, shifting functions around and allowing for the overlapping of different sports, we put the site and its connection as a whole back on the map. Thanks to its inclusive design, residents of a nearby residential care center can also make use of the infrastructure.

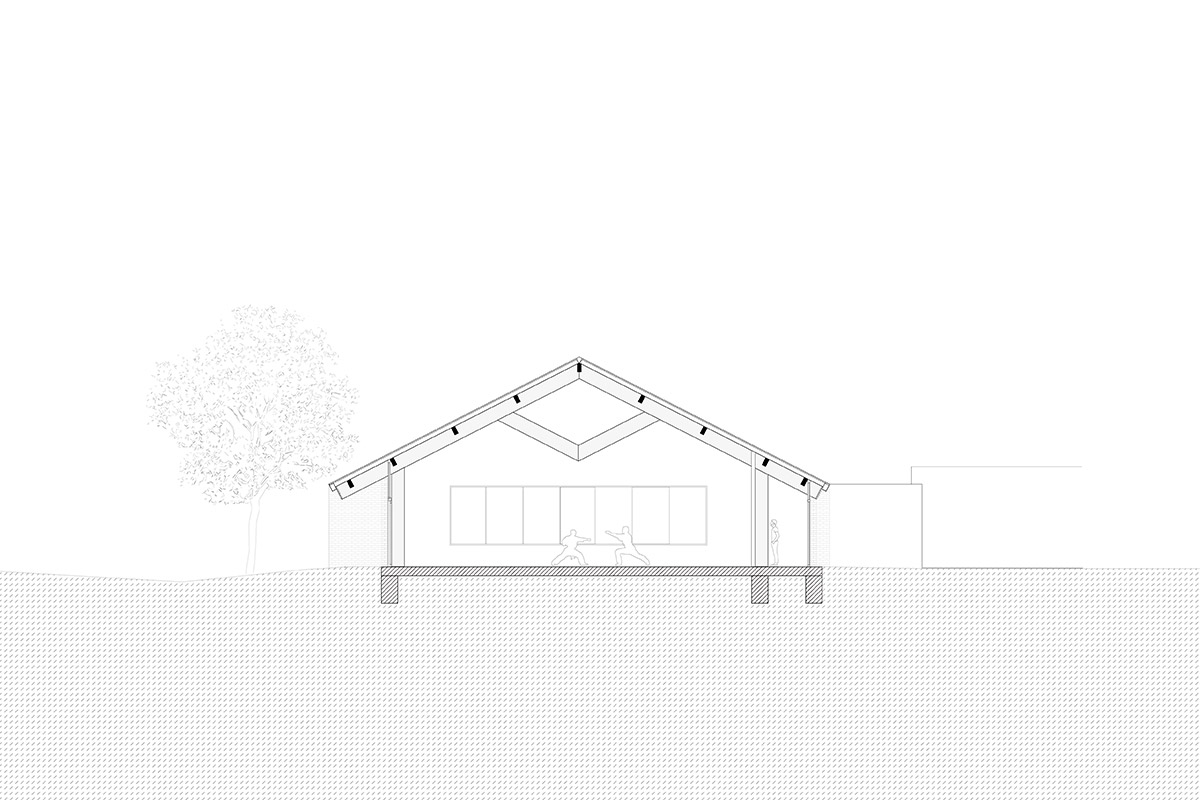

The new sports hall offers a pleasant view on the surroundings. The quality of the space will encourage its use which is further underlined by the use of warm and durable materials, so that the hall can be used not only for martial arts, but also for meditative activities in connection with the existing sports hall.

The building has been designed with the necessary attention to ecology and sustainability. An economical yet distinct wooden structure lends a surprising experiential value to the building. Formally, it is loosely inspired by traditional eastern architecture, where judo and other martial arts originated and are still practiced in such building typologies to this day.

By giving such an expression to the interior, other sports such as yoga, tai chi and dance will also want to make enthusiastic use of the building. In this way, the architecture not only enhances the experience, but also the multifunctionality and rentability of the building.

Website: b-ild.com

Instagram: @b_ild.architects

Photo Credits: © Jeroen Verrecht (projects), © Sepideh Farvardin, © B-ILD

Interview: kntxtr, ah+ kb,11/2022