20/009

Bosetti—Desjardins

Architecture Practice

New York City

«The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy.»

«The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy.»

«The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy.»

«The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy.»

«The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

We are Bosetti—Desjardins. There are two of us; David Kagawa and Harrison Nesbitt. The office started when we had returned from working abroad. At odds with much of the studio discourse at the time, we were looking for a medium to test and explore what many found to be boring or banal. We shared a similar working method that favored speed and voluminous iteration. The momentum seemingly carried itself, and at some moment neither of us can seem to truly pinpoint, we had a body of work that came to be the office we have today.

What comes to your mind when you think about your diploma projects?

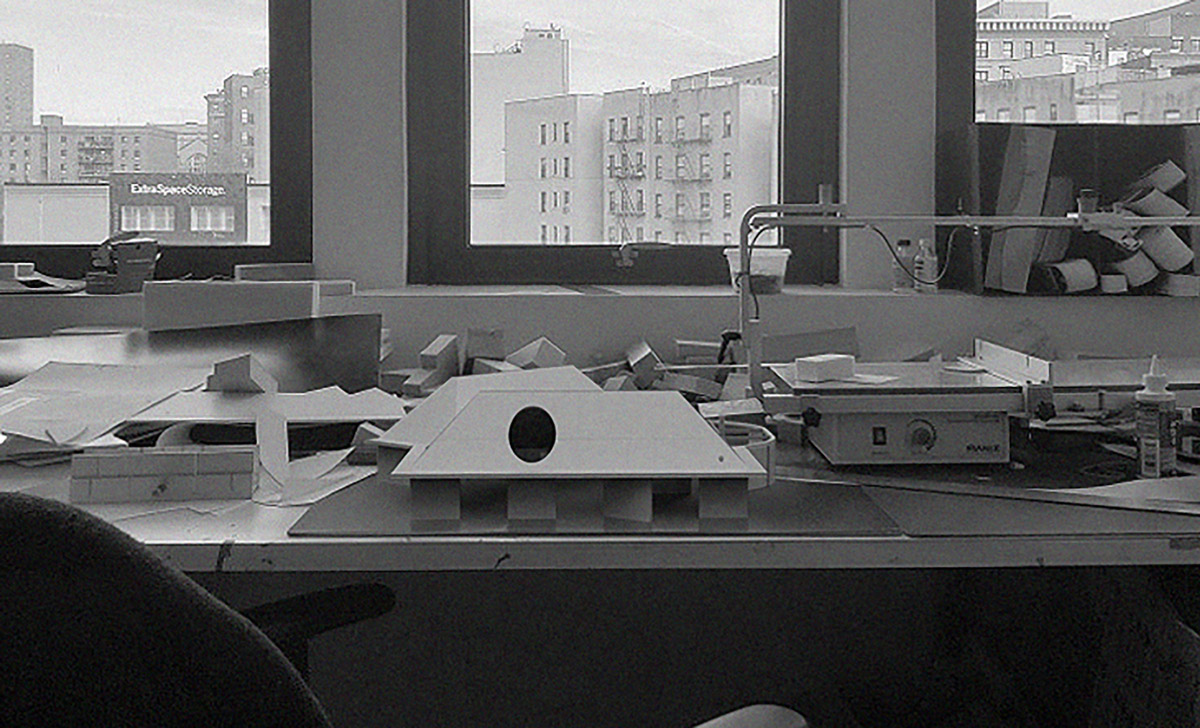

Something between a comedy and tragedy. When we started working together, we were partnered in a studio taught by Tatiana Bilbao. As the studio progressed, the group was tasked with conceiving a building for a vertical city. Later we came to realize the brief probably couldn’t have been more opposite to our office interests, the likes of which we attempted to force through what was otherwise a more speculative and imaginative brief. Despite completely missing the mark in the studio, we came to focus the pursuit of Bosetti—Desjardins, slowly beginning to understand and clarify the intention of our work.

As is all too often the case, what seemed like the most inappropriate fit for what we were sought to achieve, turned out to be the best exercise in clarification and narrative building. We thank Tatiana for her infinite patience with us, and apologize for our wobbly studio model.

What are your experiences founding Bosetti—Desjardins and working as self-employed architects?

Given our tendency to work in big sprints, often remotely, founding Bosetti—Desjardins has been as much it’s own proof-of-concept as any of the individual projects we’ve completed. There was a moment at which the office wasn’t an office at all, but a staged gallery space in Istanbul. That said, our first “office” project was “Burgus”. Working at a distance defined the same general design process we follow today. Conceptualize the project, establish base intent, iterate individually, sync for design sessions, rinse and repeat. This is largely how we operate, even now. Though we share many of the same difficulties that young practices face (read: capital), our office is a fluid endeavor with an emphasis on changing the scope of services and capacities that a design practice can offer.

Burgus

Burgus

How would you characterize New York as a location for practicing architecture? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

New York is an inherently difficult and inconvenient place for a long list of reasons. In the same breath, it’s a city with most everything in arms reach, assuming you know how to find it. It is congested, and abundant in “young practices”, providing a rich environment for inspiration and healthy competition, while highlighting the shortage of work in an oversaturated city. There is a wonderful platform for iteration and experimentation, with limitless opportunities for executing ideas.

In parallel, there is a premium on space and time, further complicating the matter of “access” within the city. Our daily operations hinge on this issue as we seek to economize everything from working location to our supply chain. At its core, New York demands an agility that we feel is aligned with our practice, yet forces a continual rethinking of strategy and best practices. New York is forever a tricky balance, a self-aggrandizing love letter and a forever pending eviction notice.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Constantly a mess, and constantly on the move. We work wherever it makes the most sense to do so.

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

Light, Space, and Time baby!

Which material fascinates you (at the moment)?

Always concrete. We are forever obsessed with concrete in any conceivable form. Concrete continues to epitomize economy and flexibility, while affording a material canvas that seems to always invite newness. We’ve been transfixed on shotcrete slope stabilization for sometime now.

Whom would you call your mentor?

Harrison: Florian Maurer (F2A architecture), the principal of the studio I first interned at. Incredibly eccentric, pedantic optimist and a true lover of architecture. His restrained aesthetic, his depth of construction knowledge and his belief in architecture as a public good continues to follow the work I do today.

David: Peter Gluck, the founder and principal of the firm I currently work at. Peter has been steadfast in his belief that thoughtfully designed architecture can make a difference. Yet, he simultaneously acknowledges the limitations that tend to plague architects and in doing so, has taken a more holistic approach to how our office operates. In this way, he has become a pioneer in architecture-led development.

Name a…

Book:

Harrison: McMaster-Carr, Catalog 110

David: In Praise of Shadows (Tanizaki)

Person:

Harrison: Thomas Demand

David: Peter Rice (structural engineer)

Building:

Harrison: Herzog & de Meuron, Roche Bau 1 versus Novartis Asklepios 8

David: OMA Seattle Public Library

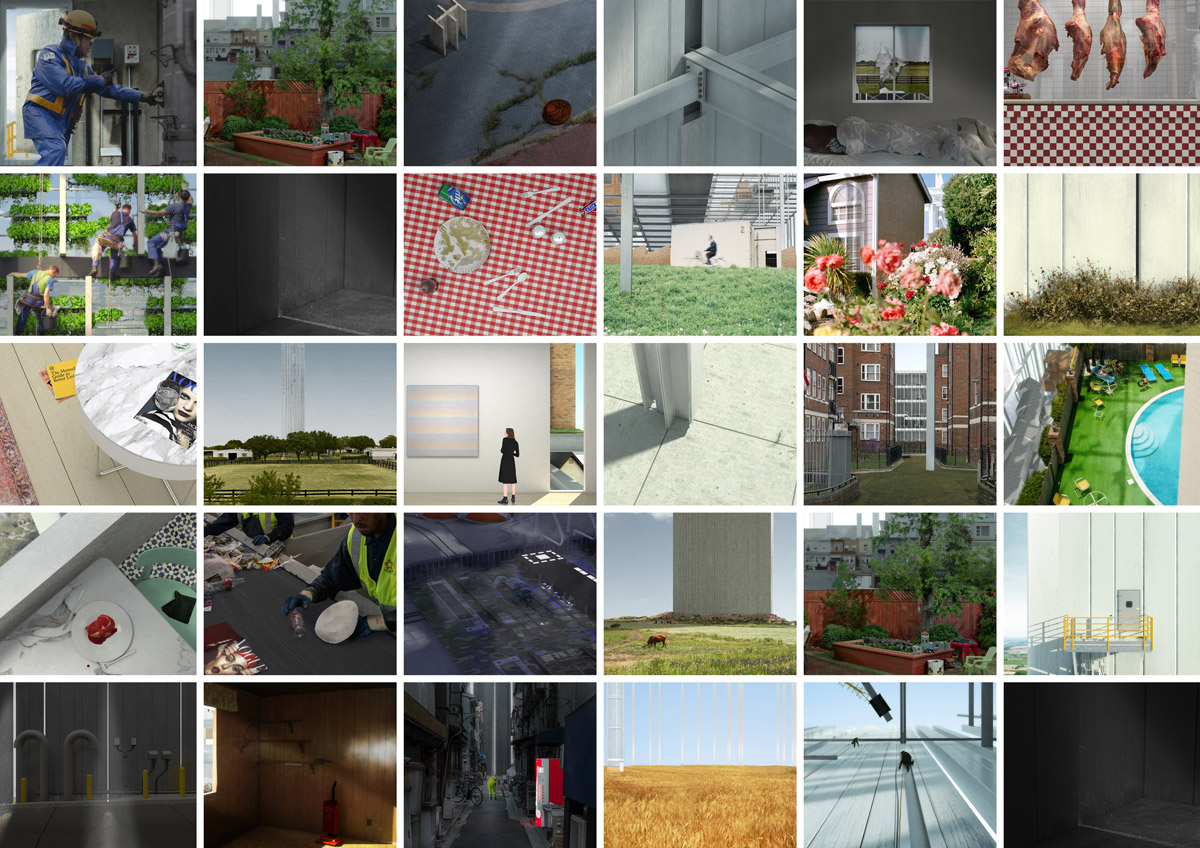

How do you communicate/present Architecture?

Poorly, perhaps. Similar to our treatment of physical material, we try to stretch ourdrawings and imagery as far as possible. Economy of production and execution is paramount to our practice and continues to define not only our communication, but our design and delivery process. In the ideal project, the entirety of the project could be understood through a simple plan/elevation diagram, a detail, a material palette and a single image. Architects talk too much, and execute too little. We would like to change that.

What has to change in the field of Architecture? How do you imagine the future?

Harrison: We certainly need to demand greater pay, though this isn’t new. With the rise of industry specialists, architecture needs to adapt and grow as a field as quickly as, if not faster than, the evolution of the professions that we depend on. The longer we hold onto antiquated ideas of our profession, the greater the risk of bringing about our irrelevancy. We, as architects, need to rethink our role in project realization, beyond our design services. The flight of architects from our field, often to gainful ends, is a testament to our valuable and unique problem solving abilities. Rather than leave, we should be looking to see how we can better expand the application of our capacities within our field.All too often we see architecture retreating into itself. Extensive written professional self aggrandizing, overcomplicated texts and intentionally opaque language only serves to further alienate us. As a field that is both so personal and present, we’ve never seemed so insecure.

David: Unfortunately, this hasn’t gone unnoticed. The way in which projects get awarded has taken advantage of this. Clearly the competition model is exploitative. As architects we need to assume greater responsibility in building, which begins by limiting the amount of work we subcontract out. Though daunting, an architect (or practice) could assume design and engineering duties, once a single entity, while pursuing investment and development opportunities within the project. It’s not difficult to imagine an ideal future, which would see a consolidation of these disparate parties and an overall, more rewarding profession for all involved in building practices. Of course, this model does not even consider the impact technological advancements may have on prefabrication - it’s critical that architects maintain some semblance of control over the development of design within large scale manufacturing and construction because I believe this is also an inevitability. Though not new, the opportunity to co-opt prefabrication as a methodology to build with will only become more widely used and we should ensure the best version of this future.

Your thoughts on Architecture and Society?

Harrison: Looking back on the previous questions, it’s probably clear we feel there’s a disconnect. We often struggle to balance viability with innovation and experimentation. Growing up in a very non-descript suburb, I’ve found that the tragic fast-buildings common in our cities and neighborhoods are largely a consequence of people not knowing what the alternative could be. Again, I feel this circles back on professional isolation. While one could certainly argue that the stick-frame buildings characteristic of developer/suburban design are a product of a capital-driven society, I look to moments (here and abroad) where architecture, in total, serves as a point of civic pride. There is a teaching opportunity through which we can not only reestablish our professional relevancy, but demonstrate the accessibility of great design.

David: They currently exist in isolation. This is a difficult subject and one I try to reconcile with on a daily basis but the idea that good design goes completely unrewarded in our current culture is a travesty - this only perpetuates the division between mass marketed/consumed buildings and considered design where the latter simply doesn’t have any way of connecting with a larger body.

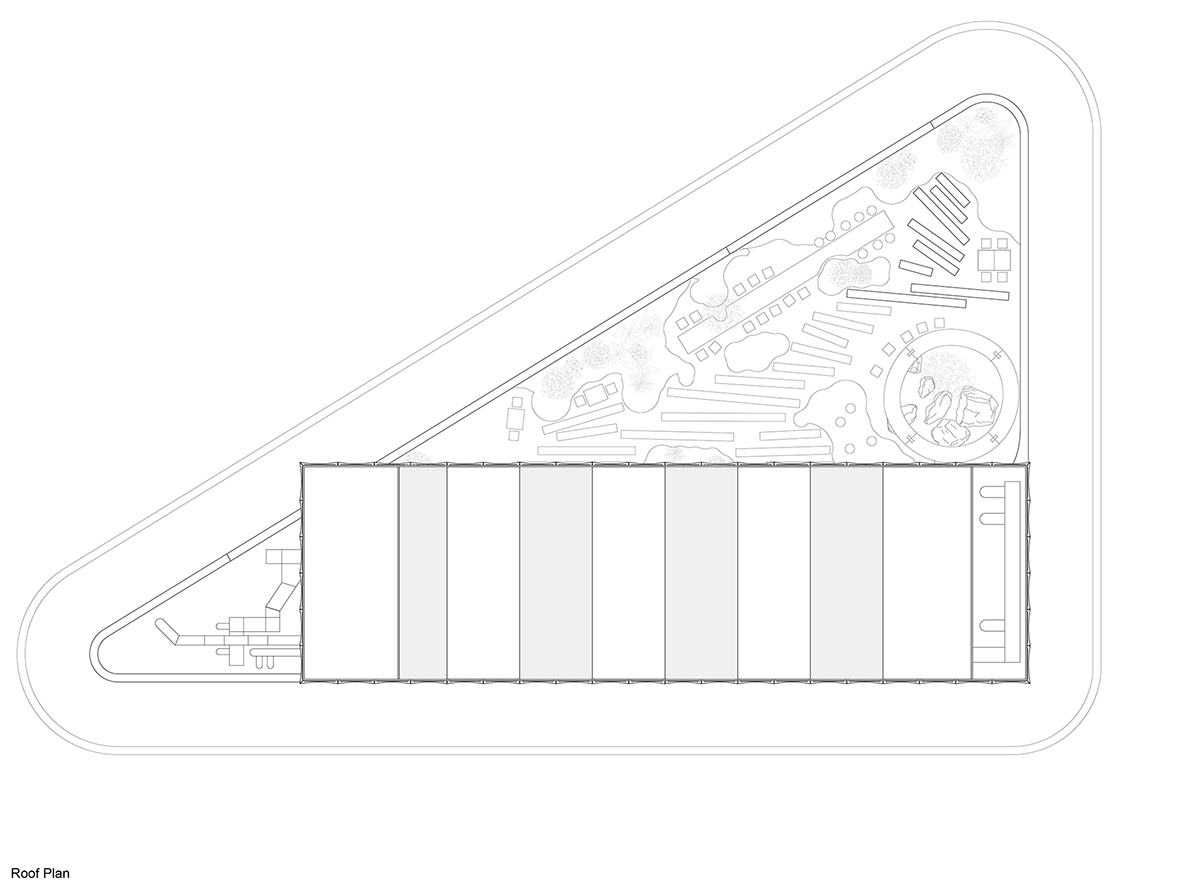

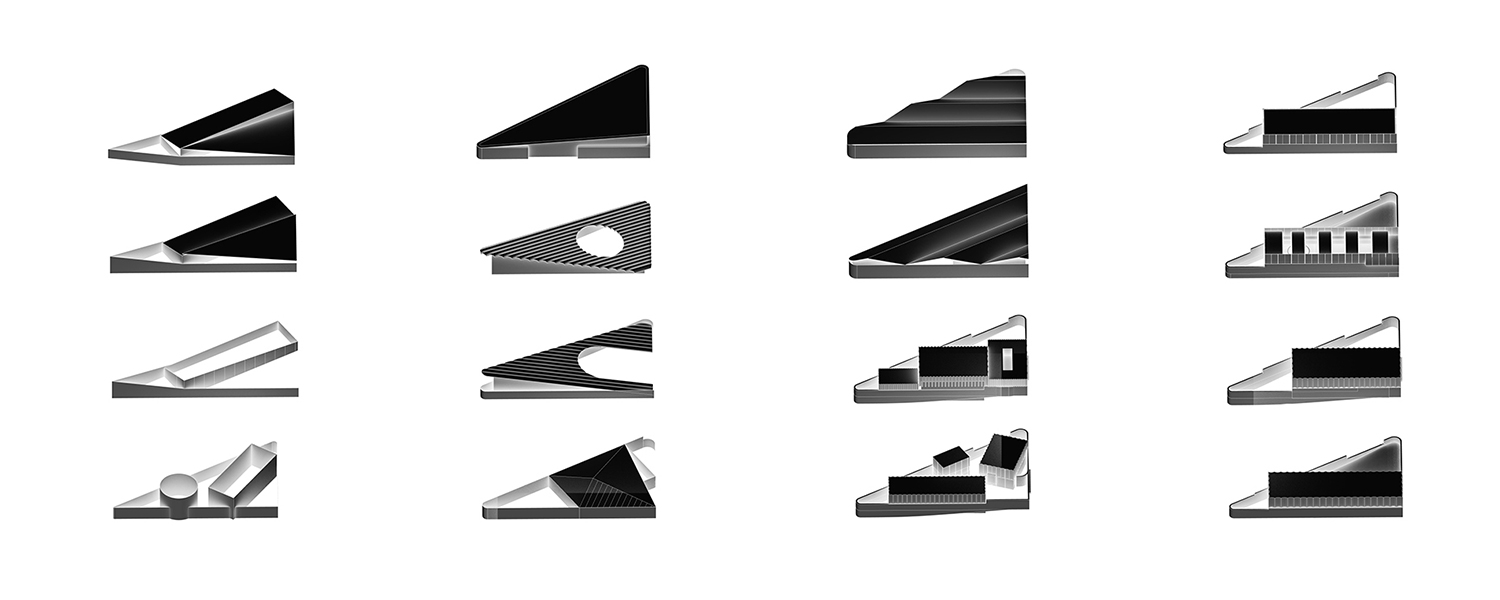

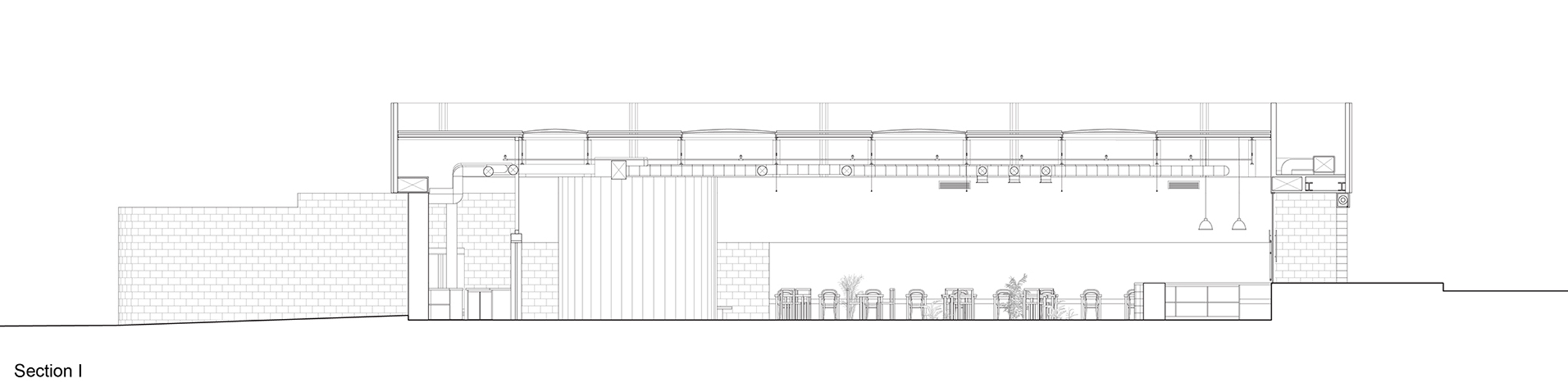

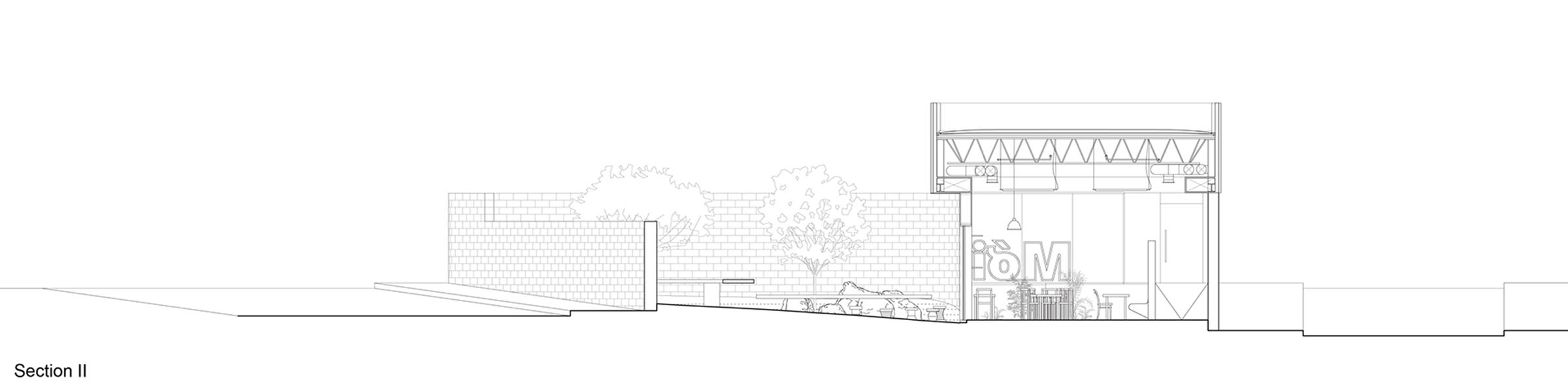

Project 1

Vietnamese Restaurant

Seattle

2020

In a nod to the street restaurants of urban Vietnam; CMU block, concrete and lightweight K-joists provide an industrial setting for a casual-fine dining take on Vietnamese street food. Restoring and reshaping the existing CMU wall of the previous building provides a non-invasive structural opportunity to elevate mechanical systems while creating a lofted interior experience. Customers descend into the space, further exaggerating spatial proportions, while over-sized sliding glass walls blur the interior-exterior divide, drawing garden into restaurant. Amongst movable wooden tables and chairs, plants grows between concrete-beam flooring. A raw material palette, sweeping ETFE skylights, and vegetation provide a stripped-down, muted backdrop for the colorful and vibrant dishes. A custom wooden furniture program complements the large communal tables, benches, and stools that seek to provide a stripped-down dining space, allowing guests to relax into the food, company and dining experience.

Project Name: Vietnamese Restaurant

Project Location: Seattle, USA

Project Team: David Kagawa + Harrison Nesbitt, founders of Bosetti—Desjardins

Project Website: https://bosettidesjardins.com/Vietnamese-Restaurant

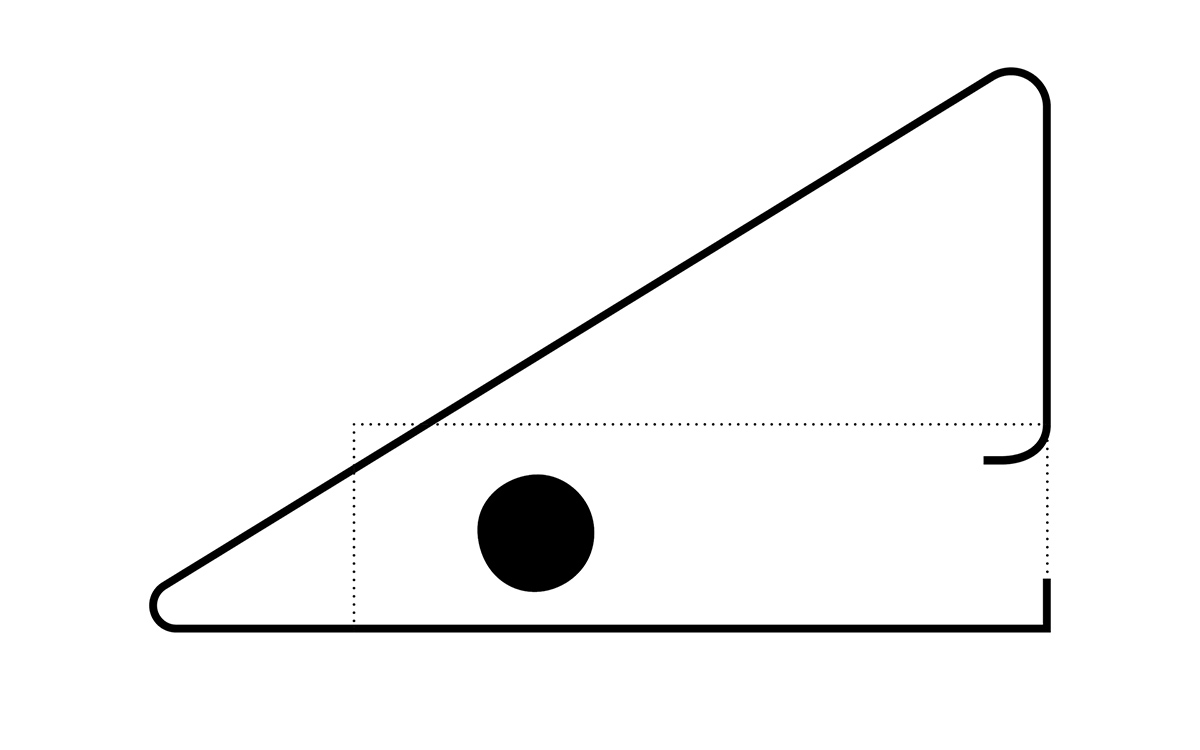

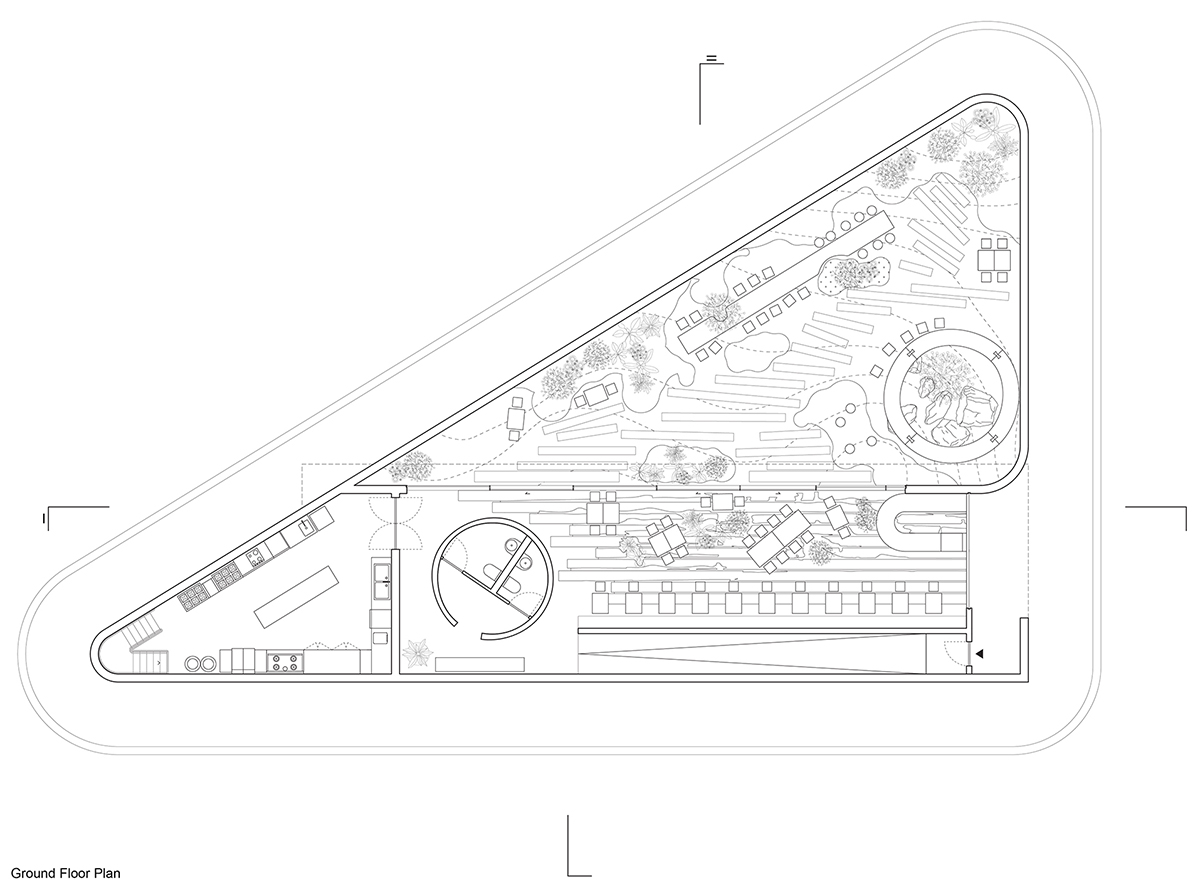

Project 2

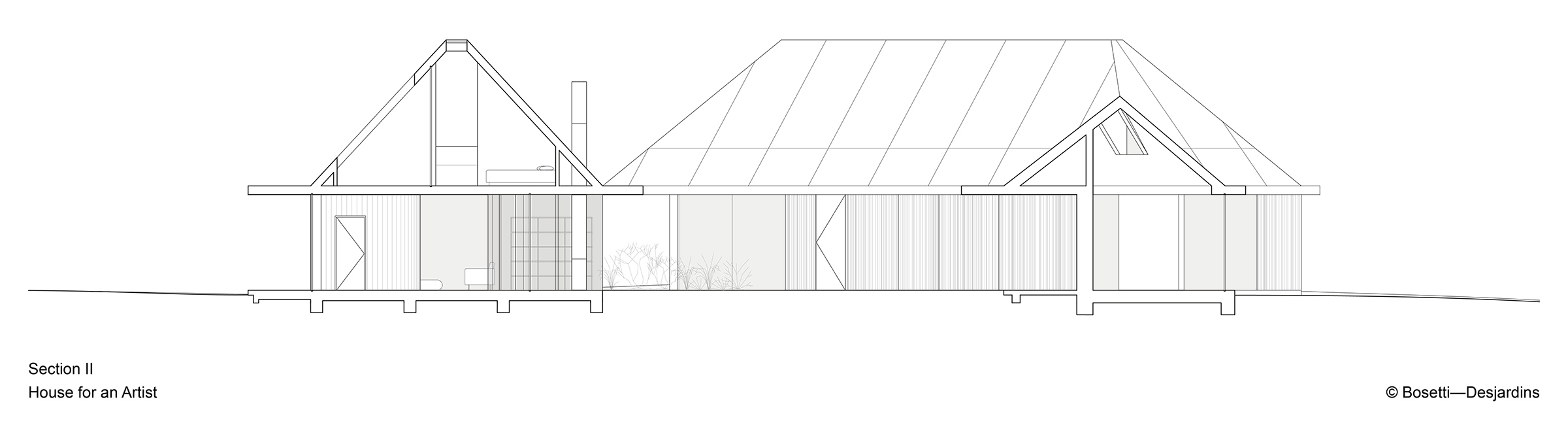

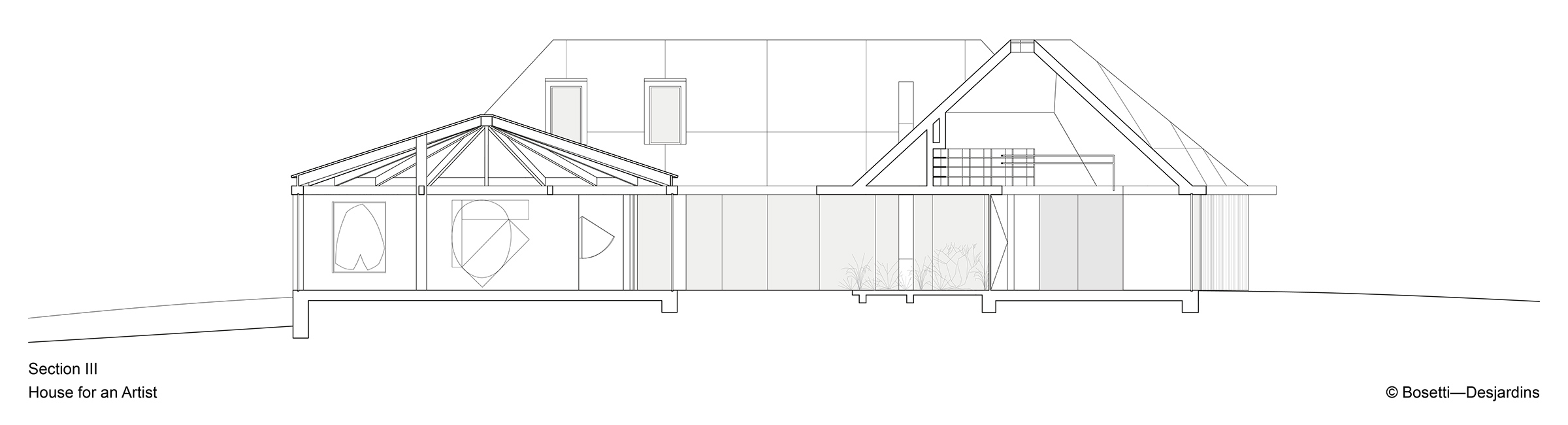

House for an Artist

Upstate New York

2020

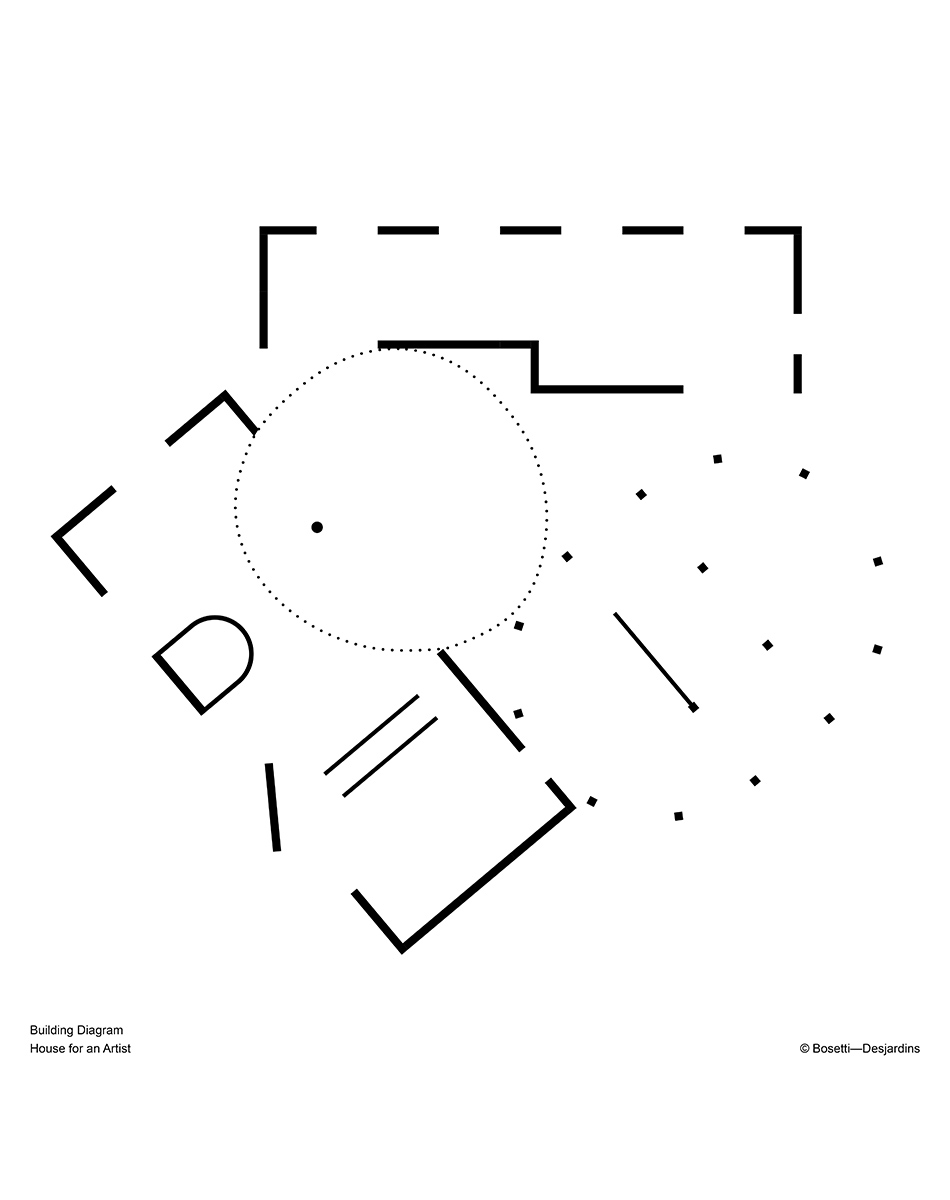

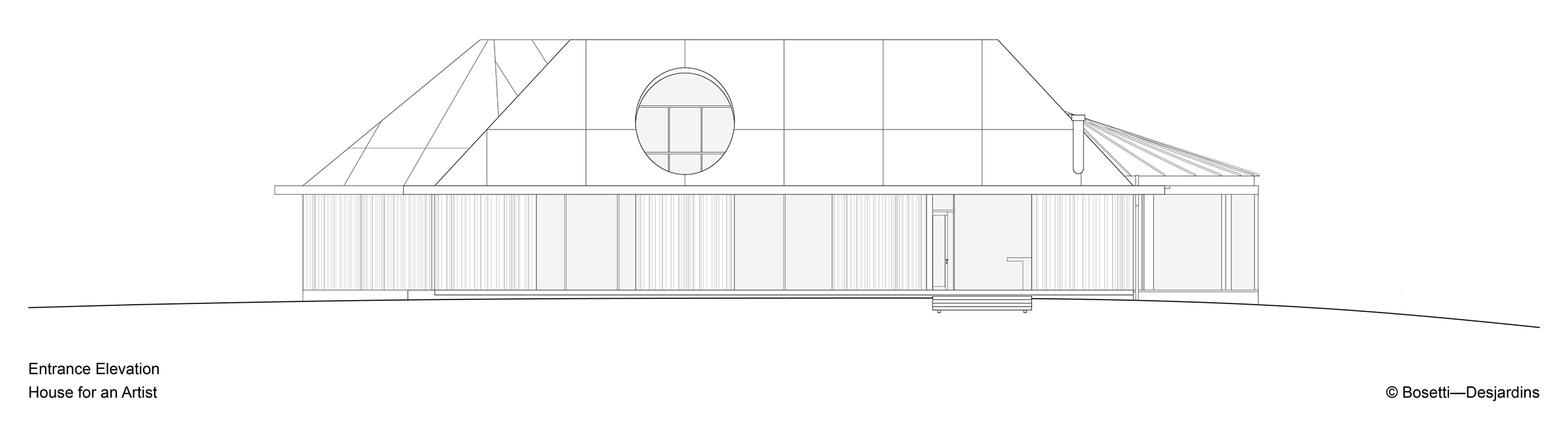

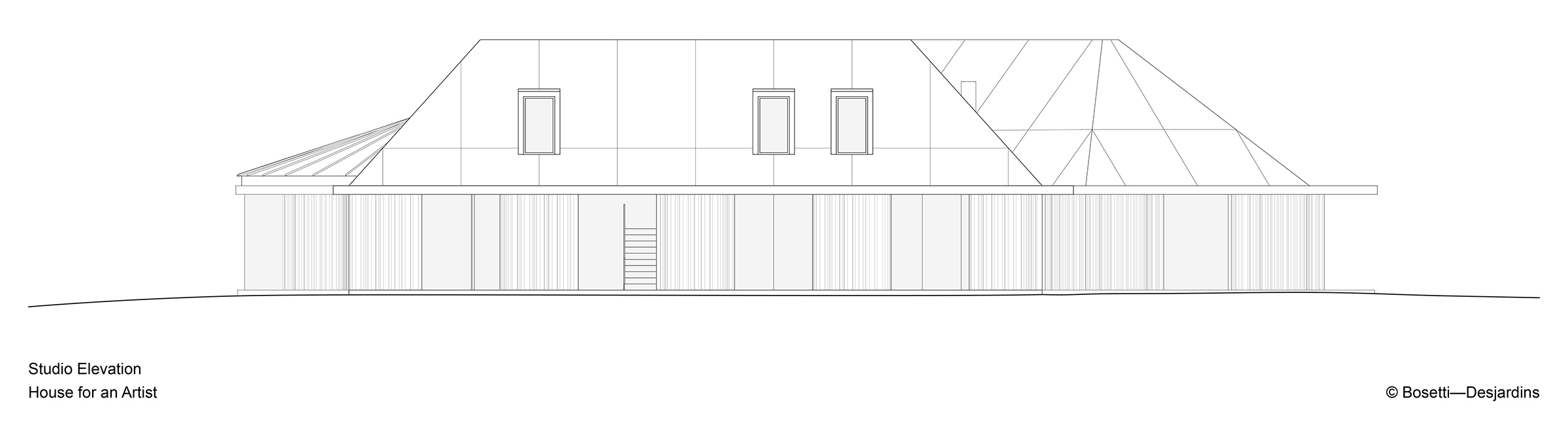

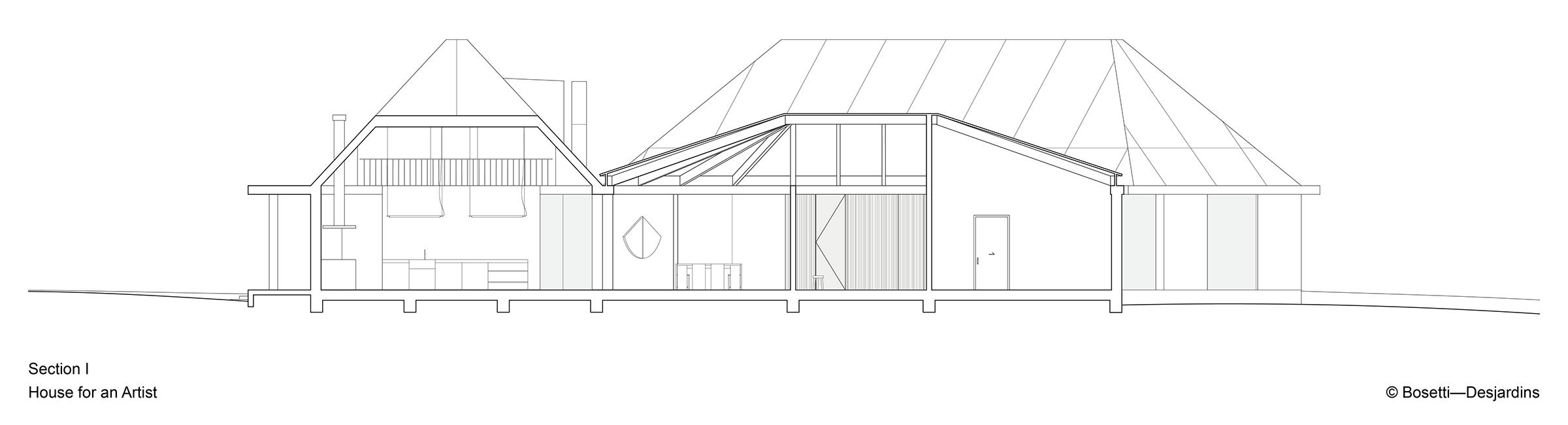

Located in rural, Upstate New York, the House for an Artist is conceived as the restrained composition of three elements: the main living quarters, a guesthouse/gallery and studio space. Three buildings, distinct in purpose, remain interconnected by an engawa and continuous roof structure, arranged to provide an intimate interior courtyard as a shared extension of each space. Floor-to-ceiling glass windows draw continuous views to the garden, while exterior courtyard reveals further inspire a curiosity that betrays the introverted presence of the three buildings. The large precast concrete panels double as decorative and structural elements, providing a rhythm and strength to the main building and studio, setting apart the function of these spaces against the pill-shaped, pinched roof guest house/exhibition space. In complement to the idiosyncratic voice of the artist, the House for an Artist achieves a quiet presence amidst soft curves of the surrounding natural landscape.

Project Name: House for an Artist

Project Location: Upstate New York, USA

Project Team: David Kagawa + Harrison Nesbitt, founders of Bosetti—Desjardins

Project Website: https://bosettidesjardins.com/Artist-Residence

Website: www.bosettidesjardins.com

Instagram: @bosettidesjardins

Contact: hello@bosettidesjardins.com

Fotocredits: © Bosetti—Desjardins

Interview: kntxtr, 01/2020