24/004

CABINET

Architecture Studio

Geneva

«We feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.»

«We feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.»

«We feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.»

«We feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.»

«We feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

Fanny Noël (FN): We are Fanny Noël and Diogo Lopes. We studied in Paris and Coimbra respectively and, in 2019, founded CABINET together in Geneva.

Diogo Lopes (DL): We combine our practice with academic contributions, currently teaching at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and the Accademia Architettura Mendrisio.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time learning about architecture?

FN: We had different paths but met each other in London, probably because we both had a shy affinity for British architecture. During our time there we created a map with all the buildings we wanted to see and made many trips around Great Britain. Doing this together for three years revealed our common interests.

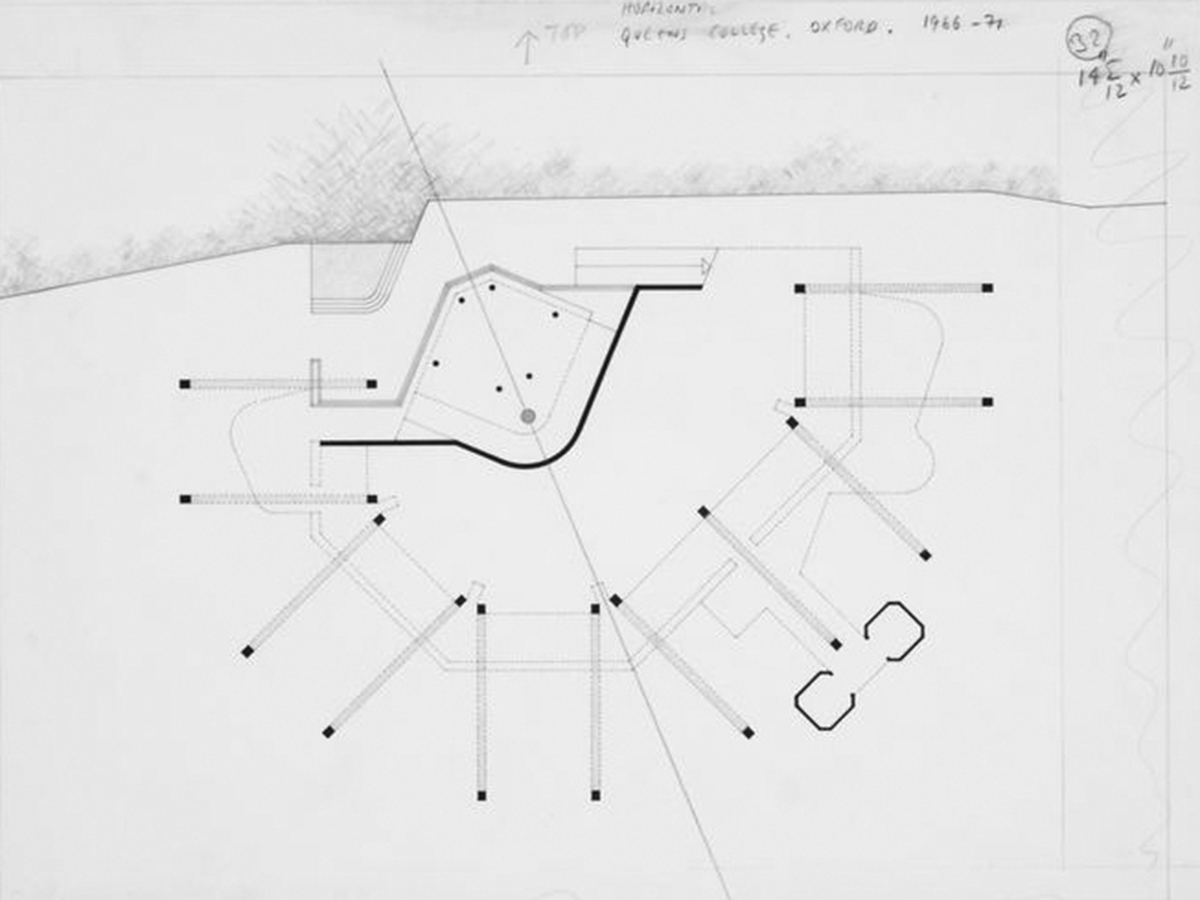

DL: At a certain point our attention shifted from the city to the landscape as a whole. We started to see an archipelago of buildings, where relationships between different figures are strengthened by the limited surface of the island.We studied buildings we had heard of but did not necessarily know deeply, like those by Edwin Lutyens or James Stirling. We discovered daring figures, each with their own formal logic, but opened to contingencies, either coming from the outside world or from an internal urge for complexity.

Rousham, William Kent © CABINET architectes / Florey Building, James Stirling © James Stirling/Michael Wilford fonds, CCA

What are your experiences founding your own office and why did you start your own projects?

FN: At first, we started working on our projects because we wanted to explore themes that were not present in our previous jobs. We realized at the time that this meant sharpening our ideas and discourse, a task we now know is never finished but perhaps the most motivating part of starting one’s own practice. One of the first themes we felt the need to explore was the figurative quality of buildings in a given territory.

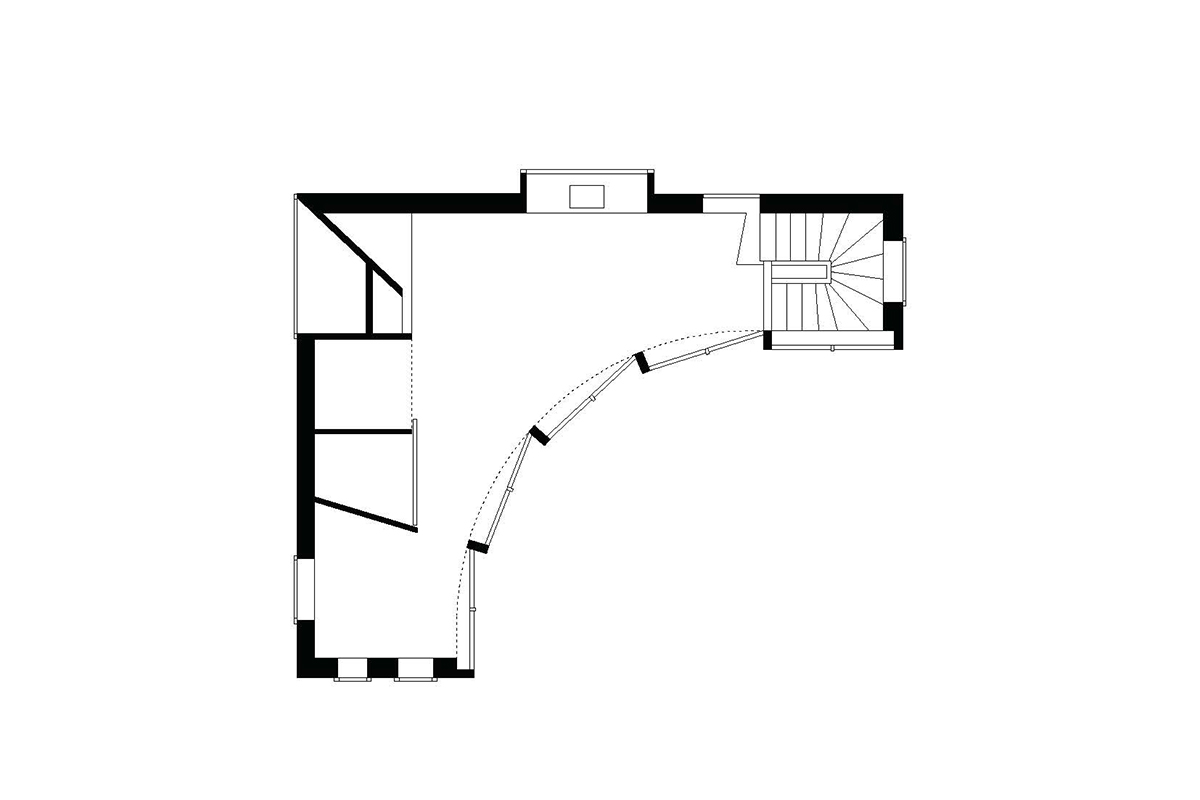

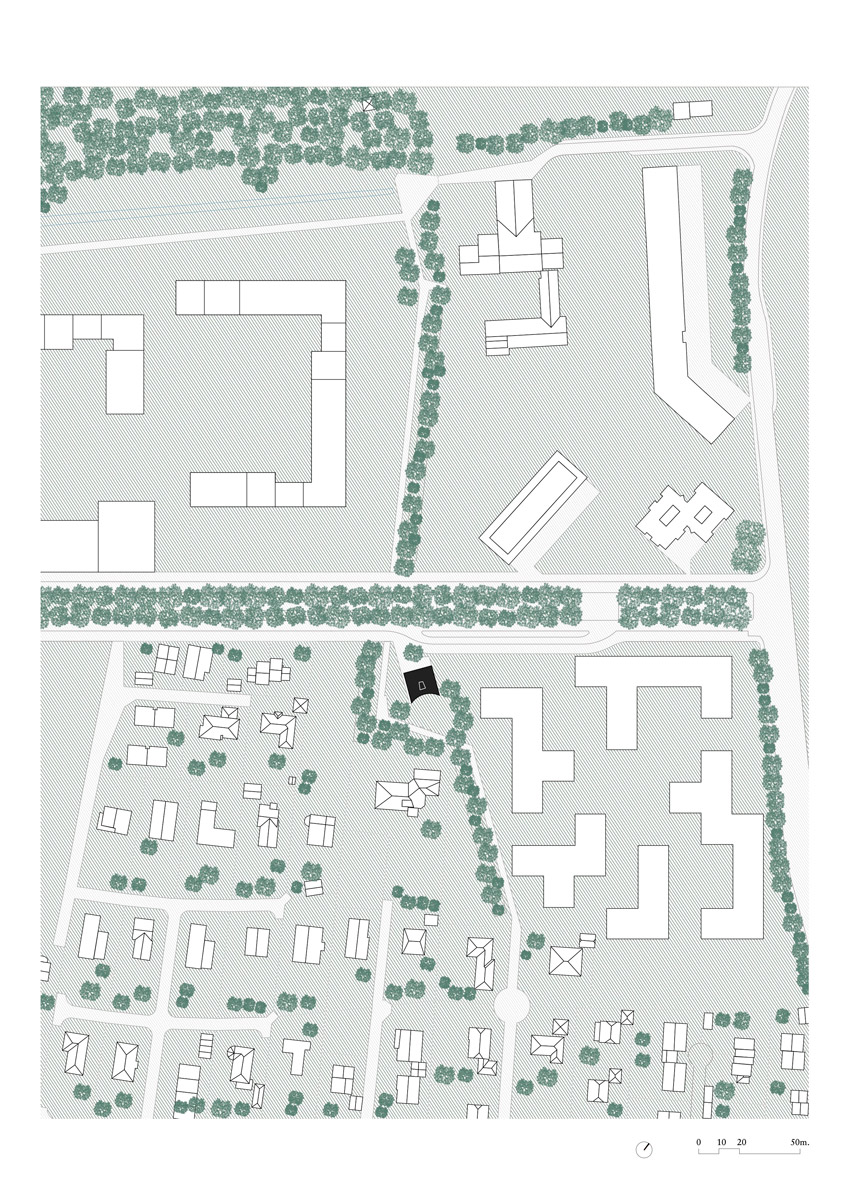

DL: Our first projects were often isolated small volumes in Geneva’s suburbs. They provided a great opportunity to articulate this idea of “figures in a landscape”, the title we gave to one of our first conferences. We had the intention of proposing architectural objects that could engage with their environment and, more precisely, with the entropy we observed. Despite their modest size, the hope is that these buildings can offer another perspective of what is around them and let themselves be enriched by it – creating a space with a curve and a group of trees, re-establishing a water cycle through a building, rediscovering an underground river, capturing the presence of multiple private gardens in one space – these were, and still are, the joys and struggles of our first years in practice.

Artist Studio, CABINET / Gardeners House, CABINET – © CABINET

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

FN: We don’t have a vision of a local architecture per se. However, we do think that projects can arise from a specific constrained situation and can speak to other circumstances. Maybe because we haven’t yet gained the trust to build on more prominent sites, most of our projects are on the city outskirts.

DL: Despite a certain idealization of Geneva’s landscape, we discovered a periphery typical to any European city, with a rather banal built fabric and disconnected natural elements. Indeed, the programs we have been working on are for the most part banal in themselves. We fully embrace this fractured condition and approach many of these contexts with the desire to make architecture that is proud and contributes to repairing such ruptures.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

FN: Before we started working together, we were both very much connected with the idea of architecture as a background to life. We quickly realized the limits of this understanding. Today, we feel the need to make an architecture that has an active role, offering articulated alternatives to our contemporary experience.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

DL: We are not sure we have an easy answer to such a question, and actually our ideas are still evolving. We have been inspired by the idea of recomposition. This comes from the intuition that we can’t continue making easy distinctions between past and future constructions, nature and artifice, the banal and the epic. These simplistic oppositions continue to cause great damage to our environment. Instead, we try to make and think through every project by composing with all these ingredients, defining what’s the most pertinent arrangement. To compose is an intrinsically architectural task, which allows us to put disparate elements together in a meaningful way.

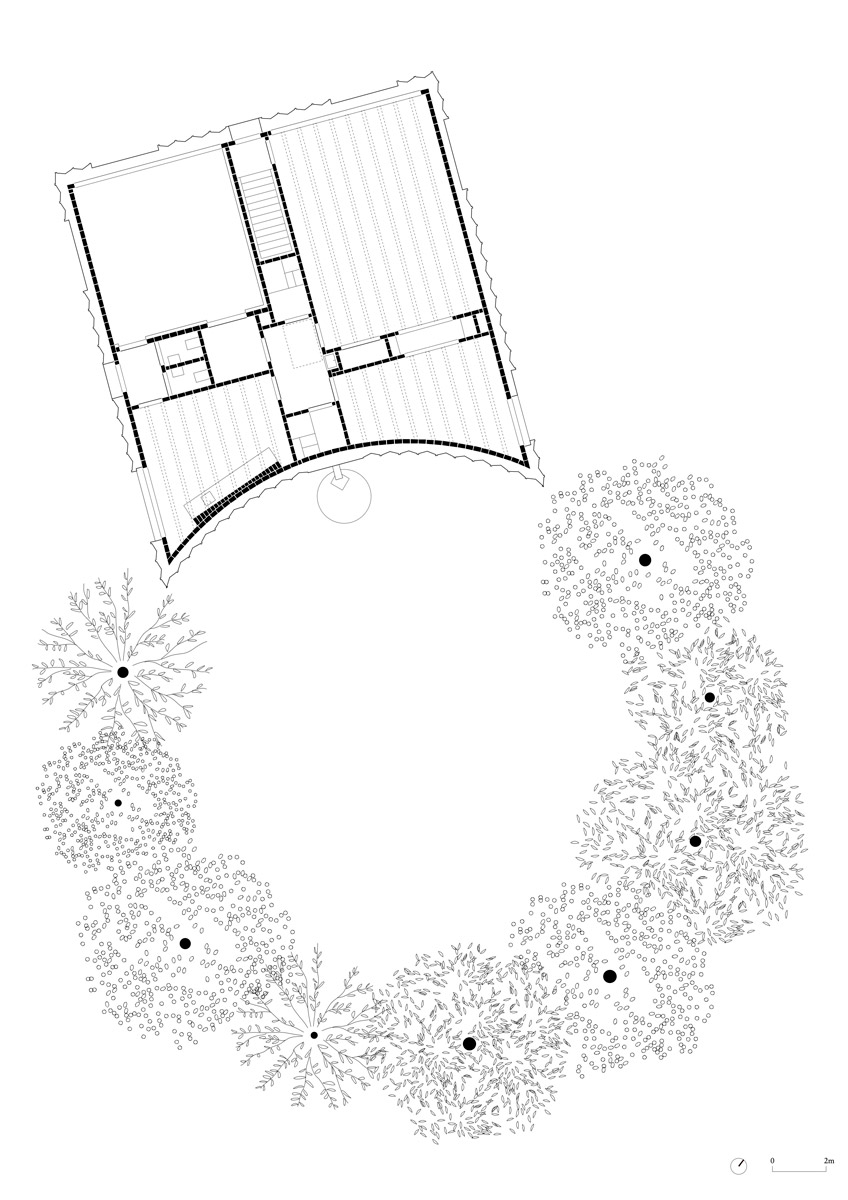

FN: At the beginning of each project, we look at these different ingredients horizontally, without hierarchy, hoping to find an unexpected and pertinent trigger for the project. This is what happened with the Gardeners’ House, where a fragment of the existing forest became the key to develop the project. The landscape became the point de départ. The space of the clearing surrounded by trees came first and the building is a complement to the vegetation. The result is a composite figure, accommodating both the circle of trees and the square outline of the building.

How do you imagine the future?

DL: The multiple challenges facing architecture as a discipline and society as a whole can only lead to an open answer. If we want architecture to be relevant, we must change both the way that it’s produced and its relationship to everything else around.

FN: On our side, we are trying to pursue the ideas we’ve just described more directly. One of the projects we are working on is the refurbishment and extension of an electrical substation. The site is an asphalt platform from the 1970’s, built in the center of a pre-existing forest, after cutting down a significant number of trees. This created two poles of biodiversity that, despite their proximity, are completely disconnected. One of the new buildings is thought of as a potential staple that would bring together these two sides by reestablishing the water cycle and allowing vegetation to grow through it. The new technology won’t require aerial cables and so we are able to recompose the demolished electrical pylons as a vertical pergola-like structure.

Name a book that was influential for your work:

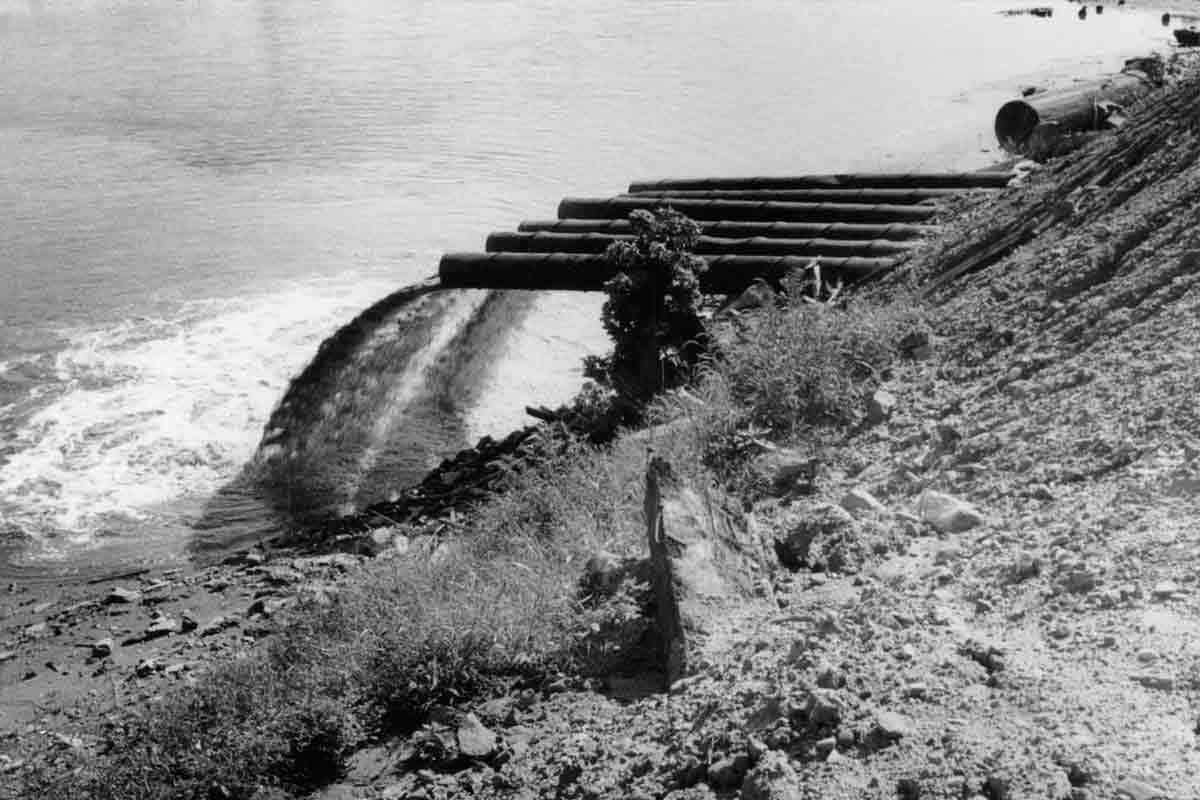

DL: “Robert Smithson Essays” edited by Nancy Holton

This book has been a companion since I was at university. We are now revisiting it as it is gaining influence on our current projects. The writings of Smithson contain concepts that are dear to us. We often speak about the idea of a dialectic landscape through the interpretation of Olmsted’s work, which itself aims to go beyond the oppositions we mentioned above.

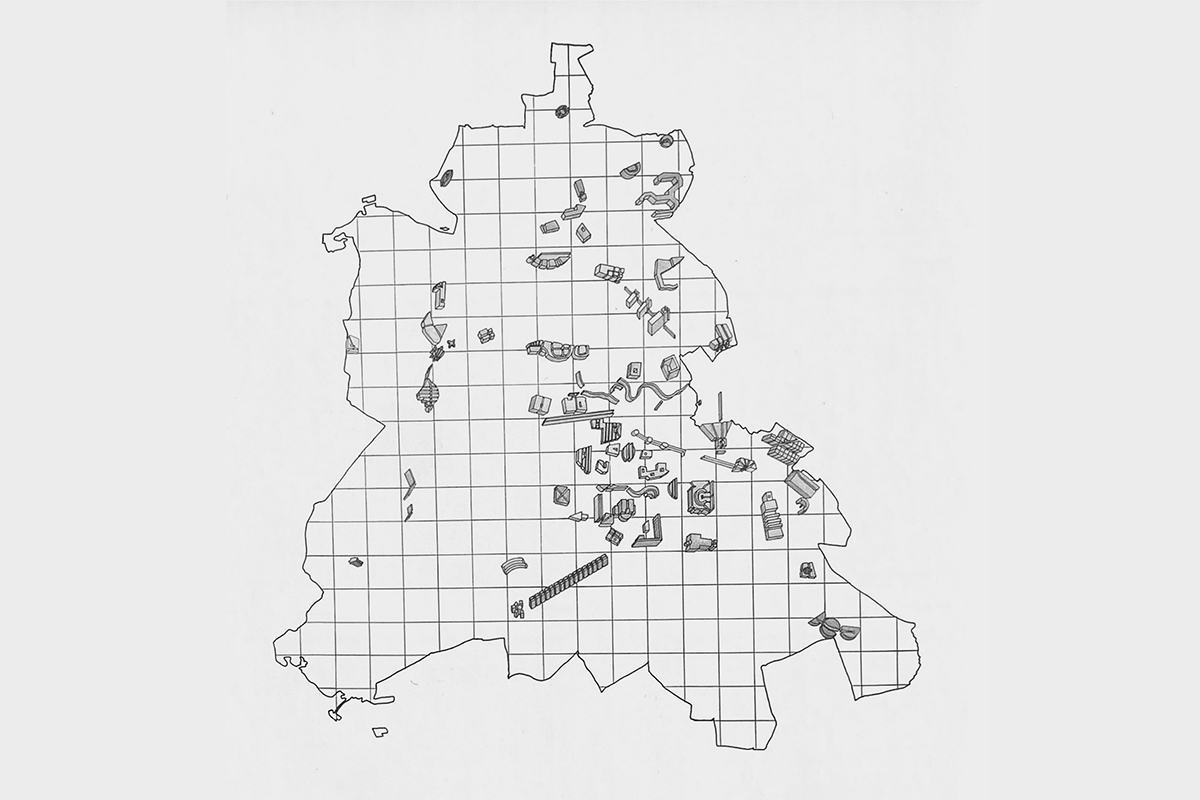

FN: “City within the city”, O.M.Ungers re-edited by Sebastian Marot

I studied in Marne-la-Vallée when Sébastien Marot was teaching there. I remember vividly his observations about suburban territories. I could have chosen several of his books, but his re-edition of City Within the City, a research project by Oswald Mathias Ungers, is particularly significant. The way he re-presents the idea of a green archipelago resonates with contemporary challenges, for example through the possibility of degrowth or consolidation of existing figures, allowing free space to exist in-between. Some of these ideas have been operative in our recent projects.

“Fountain” Monuments of the Passaic, R. Smithson © Holt/Smithson Foundation / Green Archipelago, O.M.Ungers © The City in the City – Berlin: A Green Archipelago. A manifesto (1977) by Oswald Mathias Ungers and Rem Koolhaas with Peter Riemann, Hans Kollhoff, and Arthur Ovaska", 2013, Lars Muller Publishers

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

FN: We wouldn’t want to give a definitive recommendation. However, we always encourage students to be extremely curious and to try understand what it is they like intuitively.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

FN: Our first projects were very much thought-through using physical models. Working on projects that welcome contingencies and exceptions required us to look around and reconsider them in all their complexity.

DL: After initial experimentations, we would build a proto-definitive paper model of the project and put it in a visible place in the office. By looking at it every day for a few months, we are able to understand its formal logic in depth, adjust some elements, develop detailing and feel confident about building it.

Project

Gardeners House

Geneva

2022

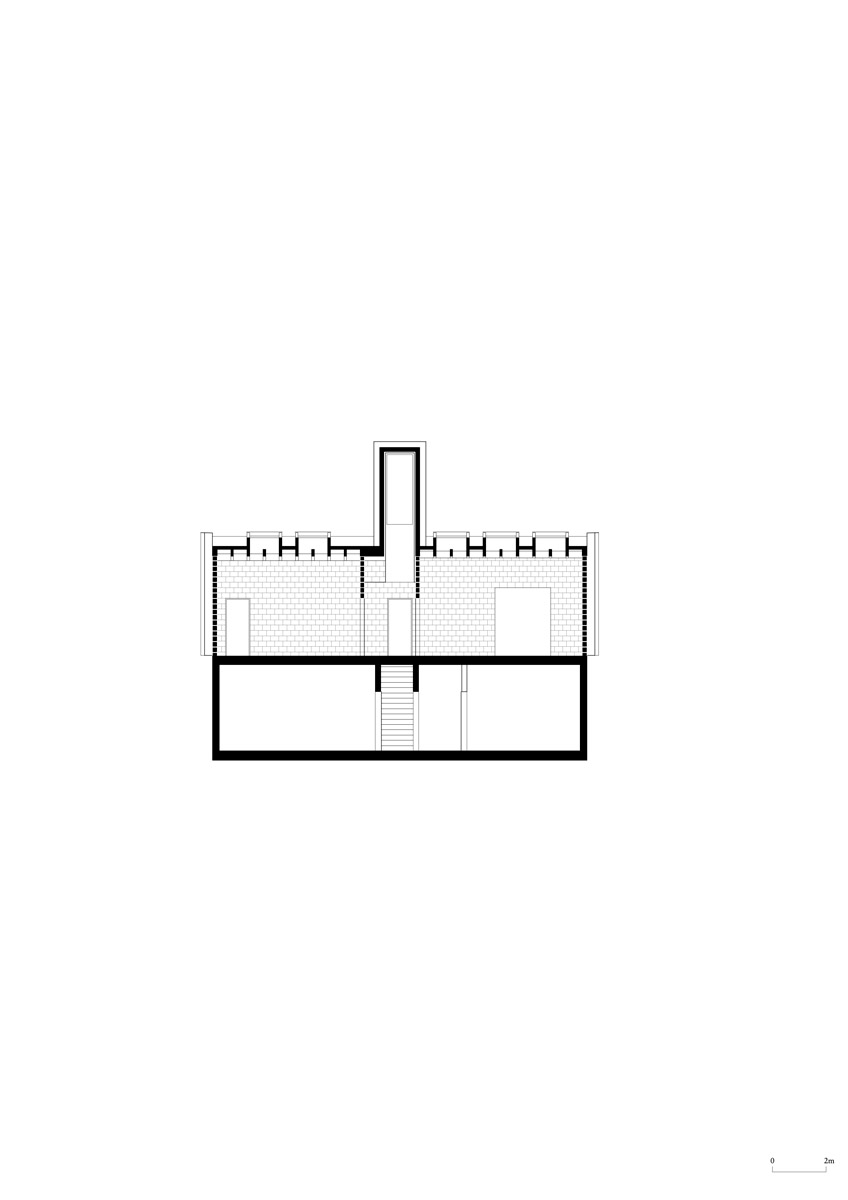

The project is conceived in dialogue with the forest of “Belle Idee,” which is partially present to the north of the site and has gradually been cleared to make way for agricultural fields and collective housing. The initial gesture was to propose a “Clearing” surrounded by a series of trees. It extends the presence of the forest while enhancing the wildlife and flora of the place. The volume primarily serves as a complement to the vegetation circle with its curved facade, which incorporates a fountain evoking a Nympheum. It provides a new shaded leisure space open to the residents.

This gesture is reinforced by the presence of a lantern on the roof, which appeals to the passers-by and accentuates the figurative quality of the volume. The scale and the composition of the façades suggest that it is the last house in the residential neighbourhood. Its uniqueness lies in the inversion of the conventional construction order. A delicate folded wooden facade, coated in blue stain, extends the sky down to the base of the clearing and dresses a more robust series of terracotta brick walls on the inside. A beam structure, resembling a pergola, filters the zenithal light that illuminates the workshop spaces.

Website: cabinet.archi

Instagram: @cabinet.architects

Photo Credits: © Sven Högger

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 03/2023