«Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural.»

«Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural.»

«Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural.»

«Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural.»

«Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

I am a trained architect, professor at the School of Design at the University of Quebec in Montreal, where I teach history, theory and practice.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture ?

I was always interested in how things came together without really knowing what architecture was. I come from a small town in northern Quebec where no one ever talked about architecture but where most people knew how to build a house or fix it. When I left to study, it seemed appropriate to complete a technical degree in architecture where one learns all the knots and bolts of construction. I did well but I couldn’t really see myself drawing construction details and wall sections in an office.

So I decided to do an undergraduate degree in design, in a program that teaches industrial and urban design as well as architecture, in a way that scales intermingle and allows to move back and forth between objects, space and city. It really widened my understanding of what architecture can be and so I felt comfortable moving on to a professional masters in architecture in Vancouver. I then completed my internship in New York City, but when time came to take the exams to become a licensed architect, I decided I might not really be fit for practice (too fast pace, too many uncertainties, but mostly not enough time to dive into “irrelevant” questions) and so I signed up for a PhD back in Montreal in the history and theory of architecture, looking at the purpose of uselessness in our built environment. Following the PhD I was offered an appointment at the School of Architecture at AUB, in Lebanon and came back again to Montreal in 2012 as a professor at the School of design, where I did my undergrad.

Warchée Videoseries with Carole Levesque

Where do you see the future of women in academia ?

A little bit more than half of students in architecture schools are women. The number of female professors is now on the rise but somehow, studios are still most often taught by men. I don’t know whether women bring something different to studio or not, but I wish there would be more of us teaching studios if only to show our students that being a designer is also something women excel at.

What was your diploma project about ? Does it still have an impact on your current work ?

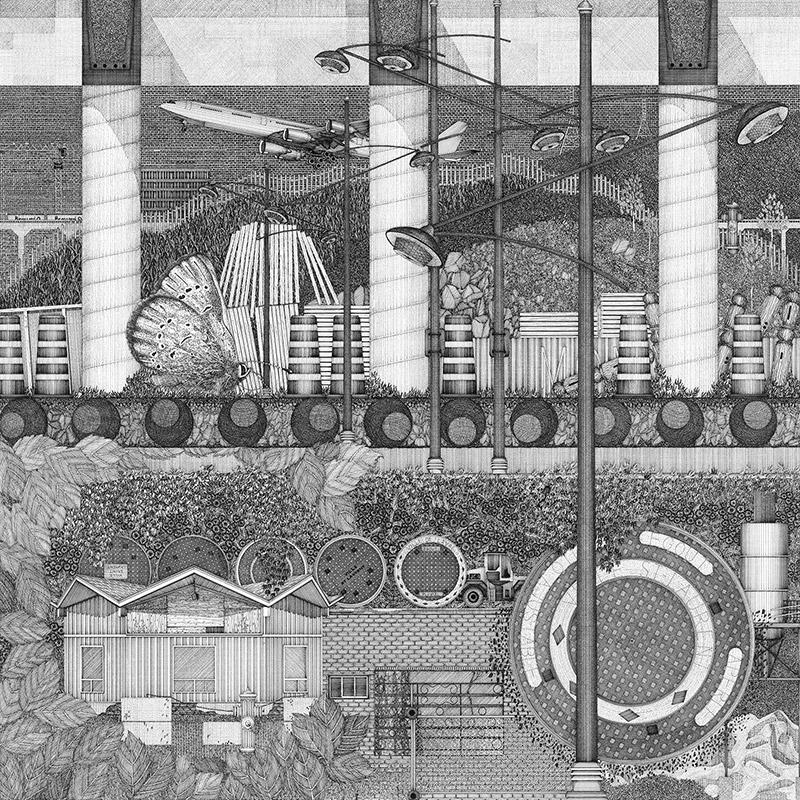

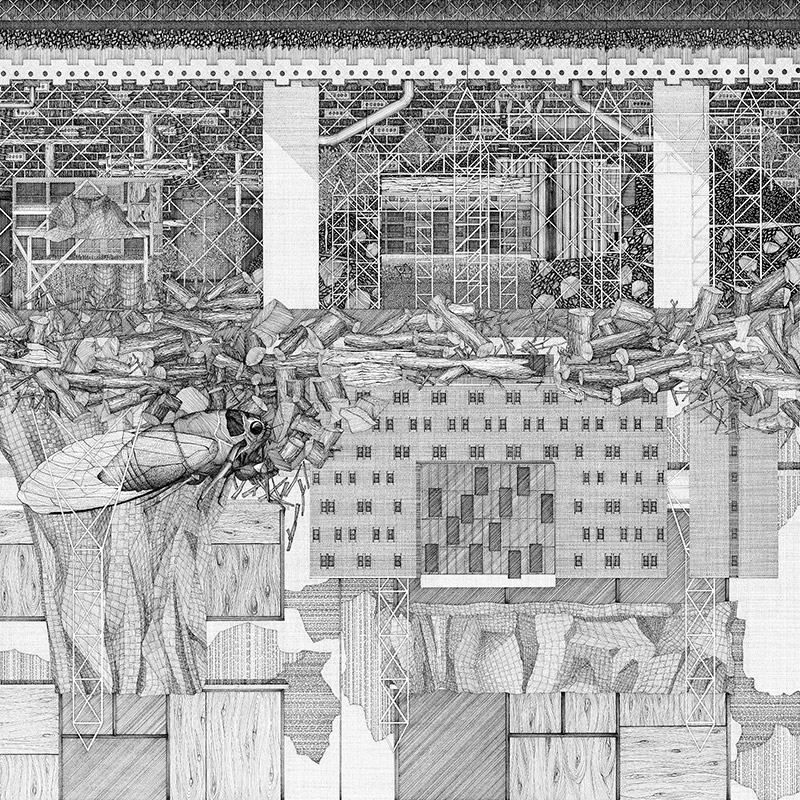

My undergrad project was a tower which didn’t have an envelope, nor much shape or structure. I designed a tower I wasn’t really interested in. What was of interest to me was how one might link the underground to the street, how to place the tower so as to leave as much free space on site and think of ways to make it worthwhile to walk up the stairs instead of taking the elevator. For my graduate project I designed three buildings which had no program. After presenting to the jurors for 20 minutes, the first question I was asked was: but what are they for? And I responded that they were for what one imagines fit to take place in them. During my PhD I worked on temporary, small scale architecture as a means to build a critical stance upon permanence in the city and find purpose in these installation’s apparent uselessness. And now, in my academic research, I work on vagueness, building representations of derelict urban areas, seeking the stories they might have to tell and lessons that might be learned from them. I think I never really left my school projects behind and that it has rather been a long evolving process through all these years.

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture ?

Architecture to me is about taking part in building relations with others, within or with communities as well as with the environment, be it built or natural. There isn’t one way of doing it, there isn’t a simple answer to it. It is dynamic, we always have to understand what is unique about a given context and act with as much generosity as possible towards it.

How do you communicate/present Architecture ?

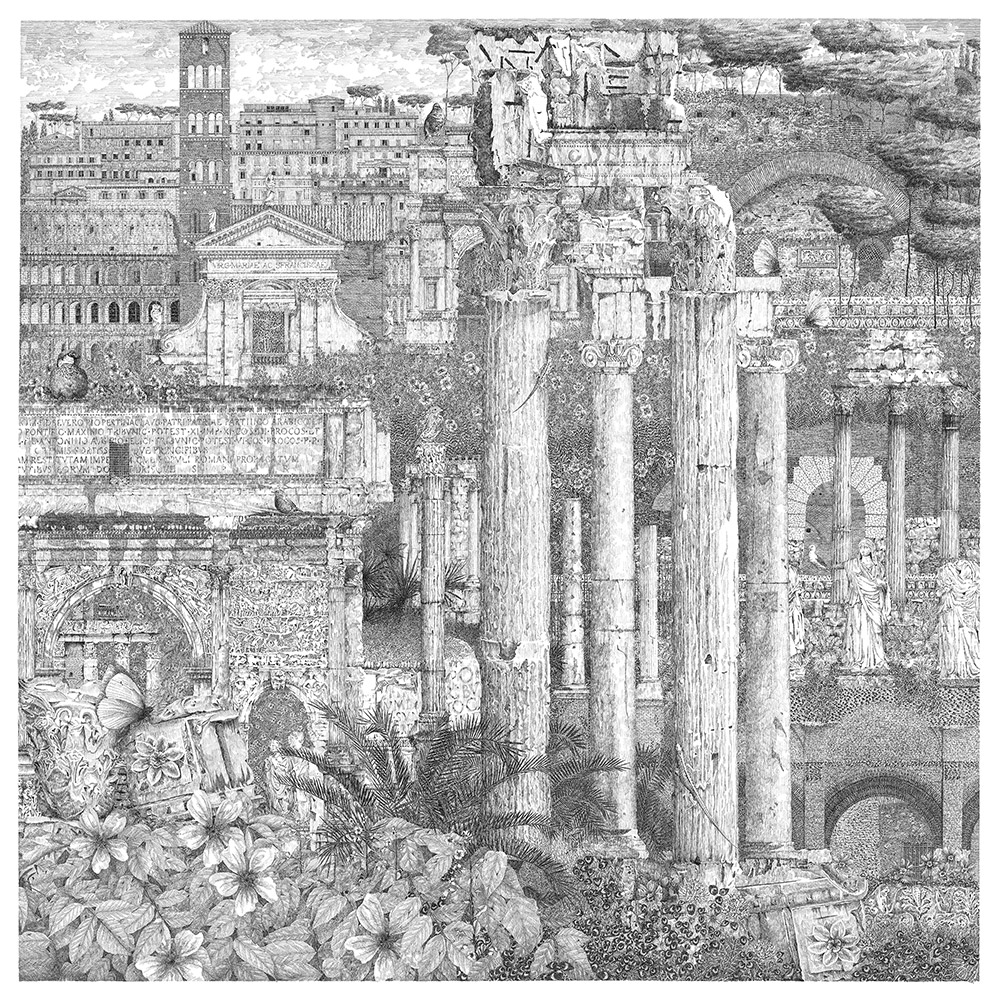

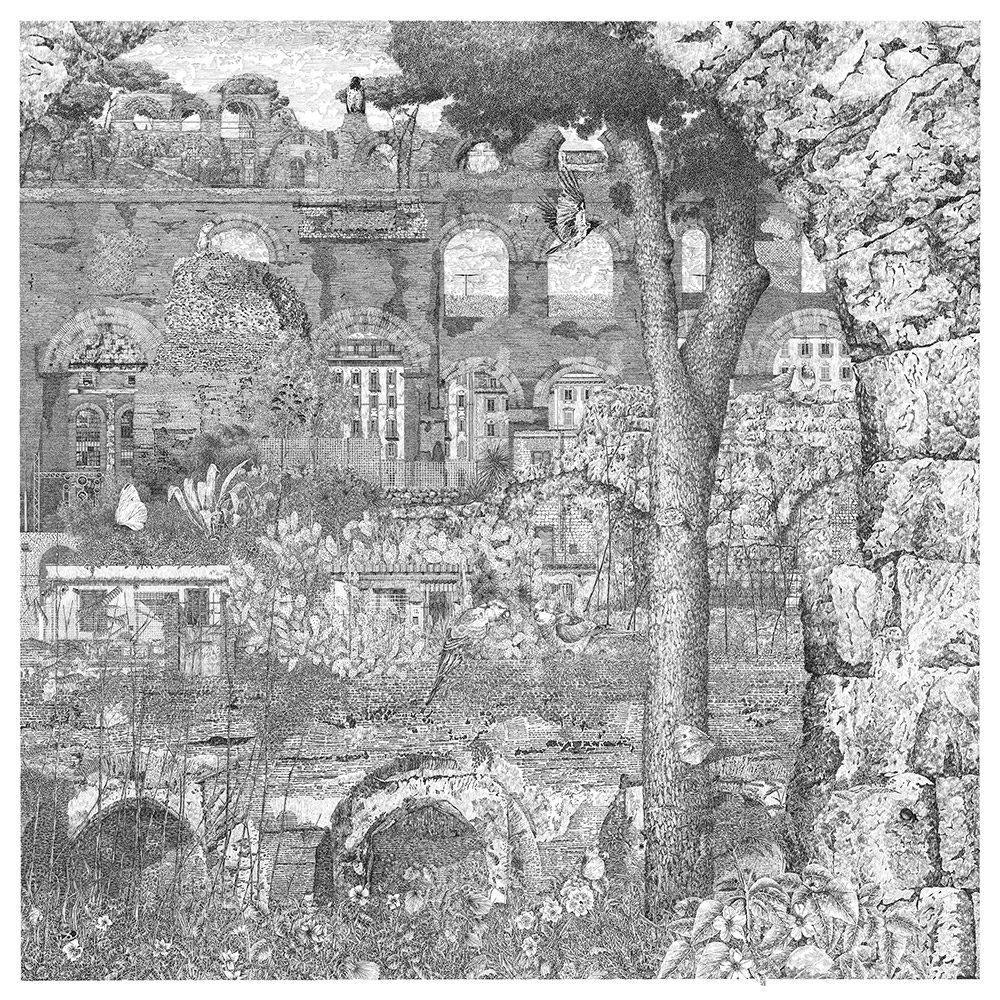

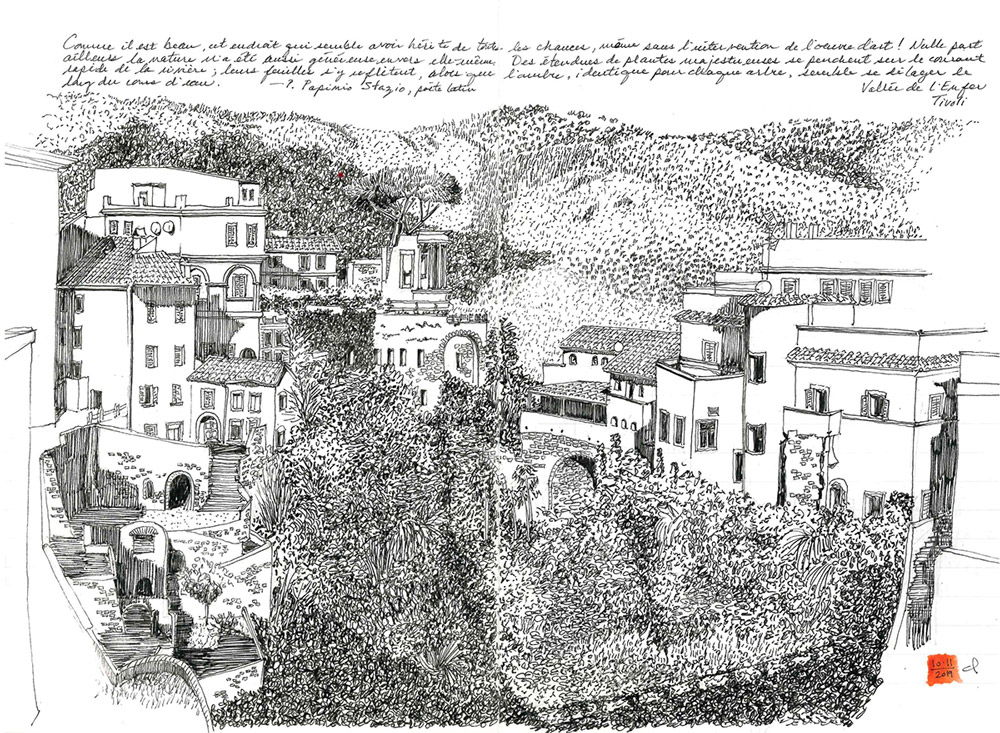

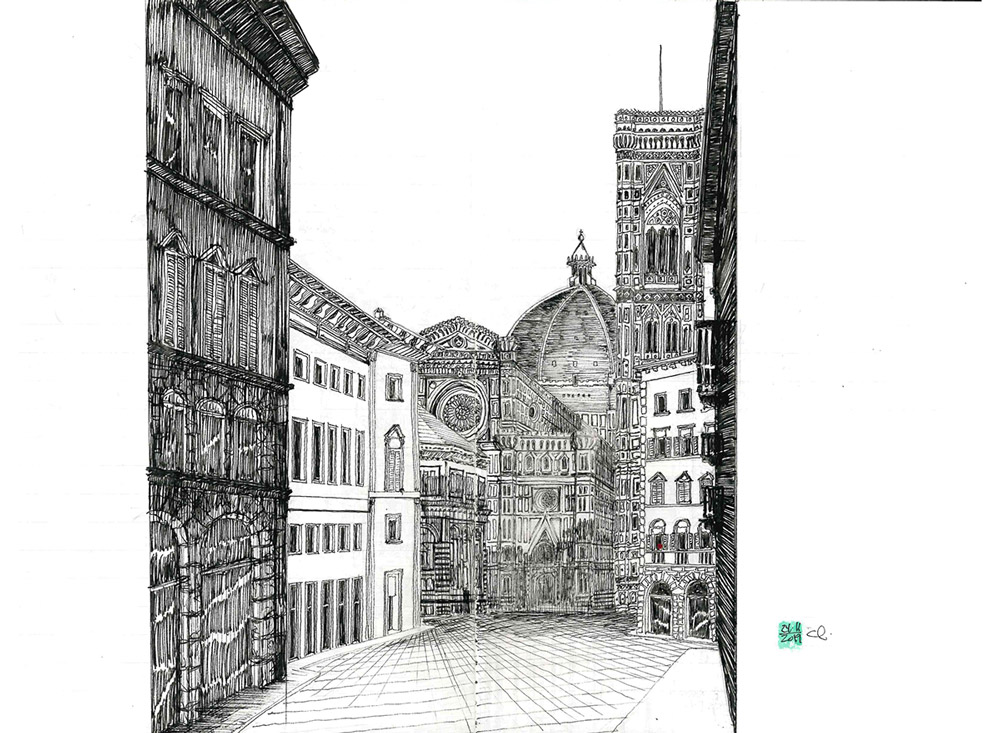

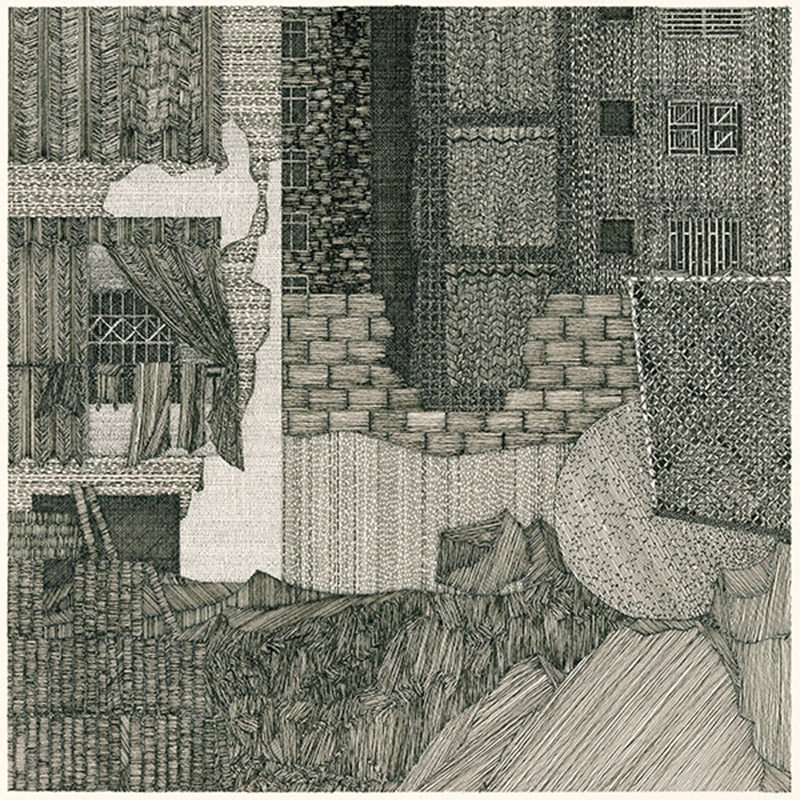

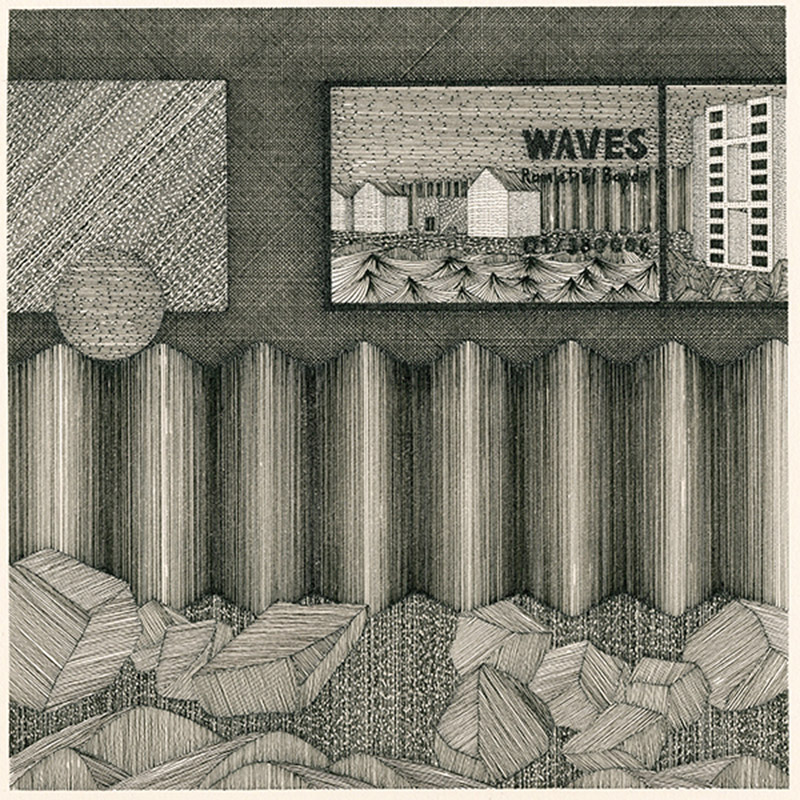

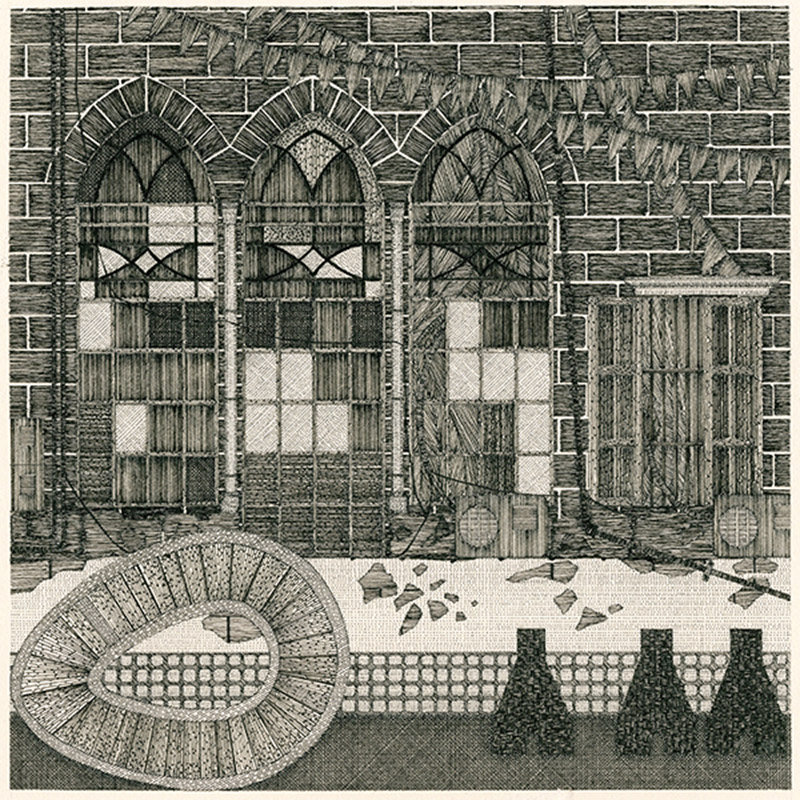

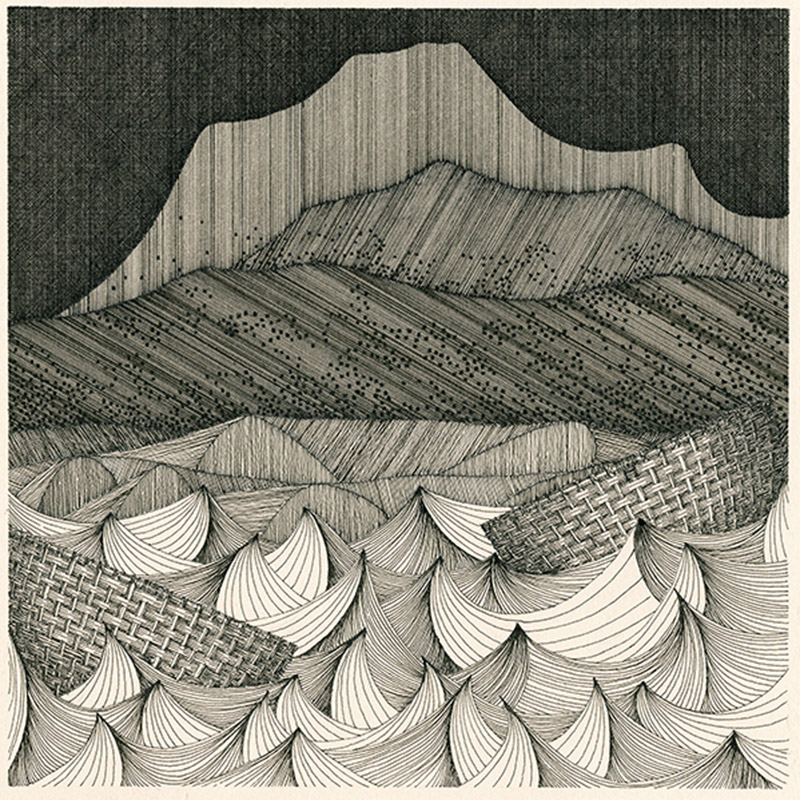

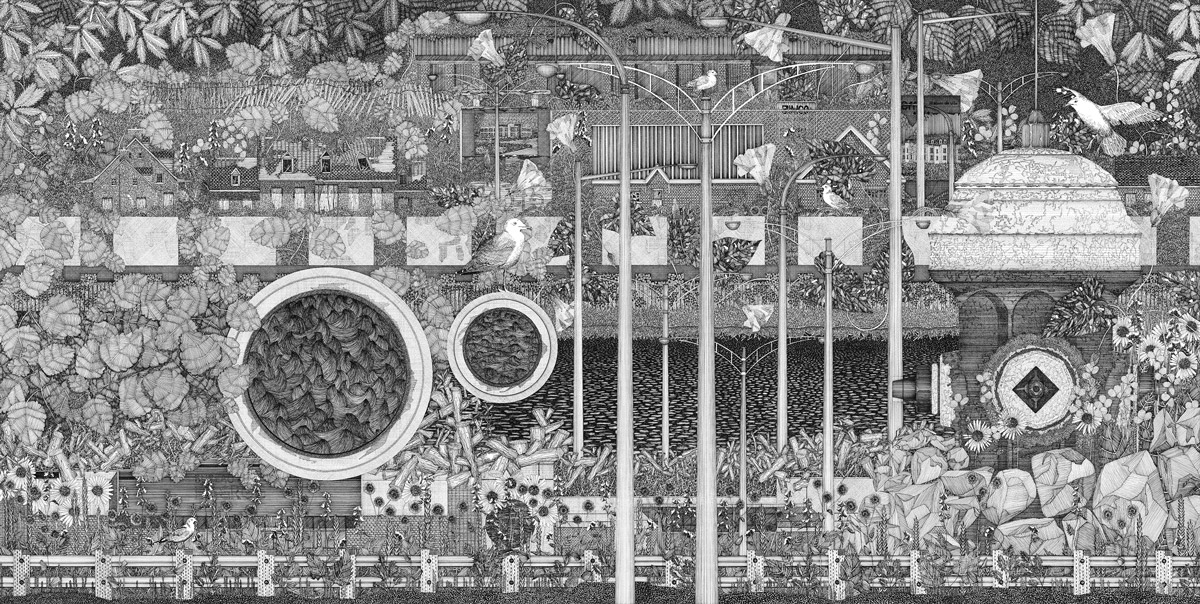

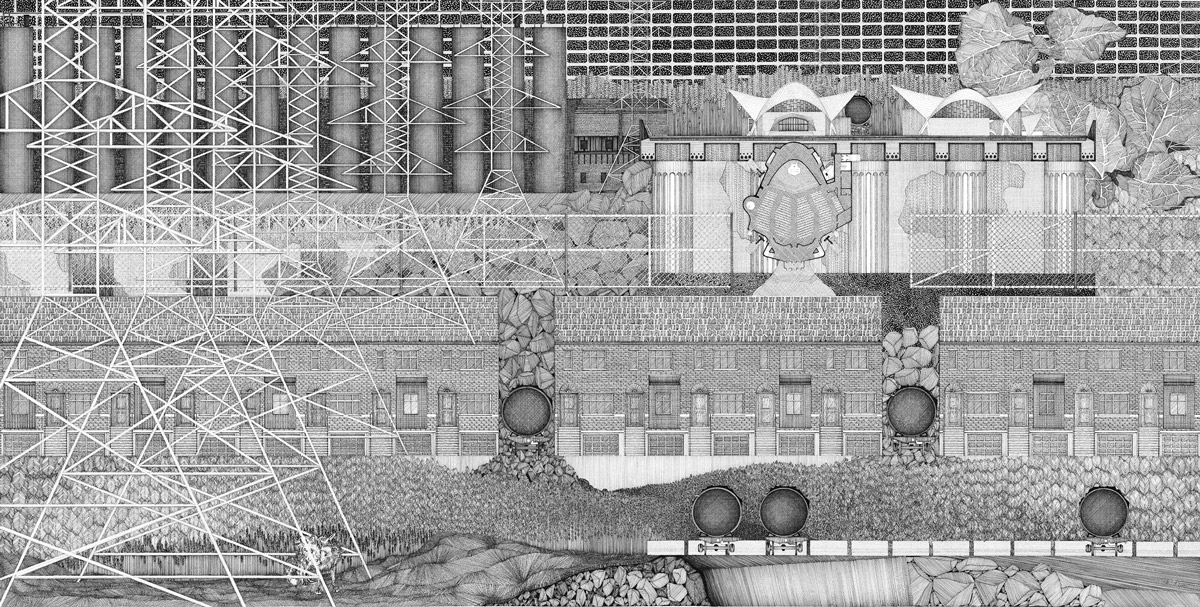

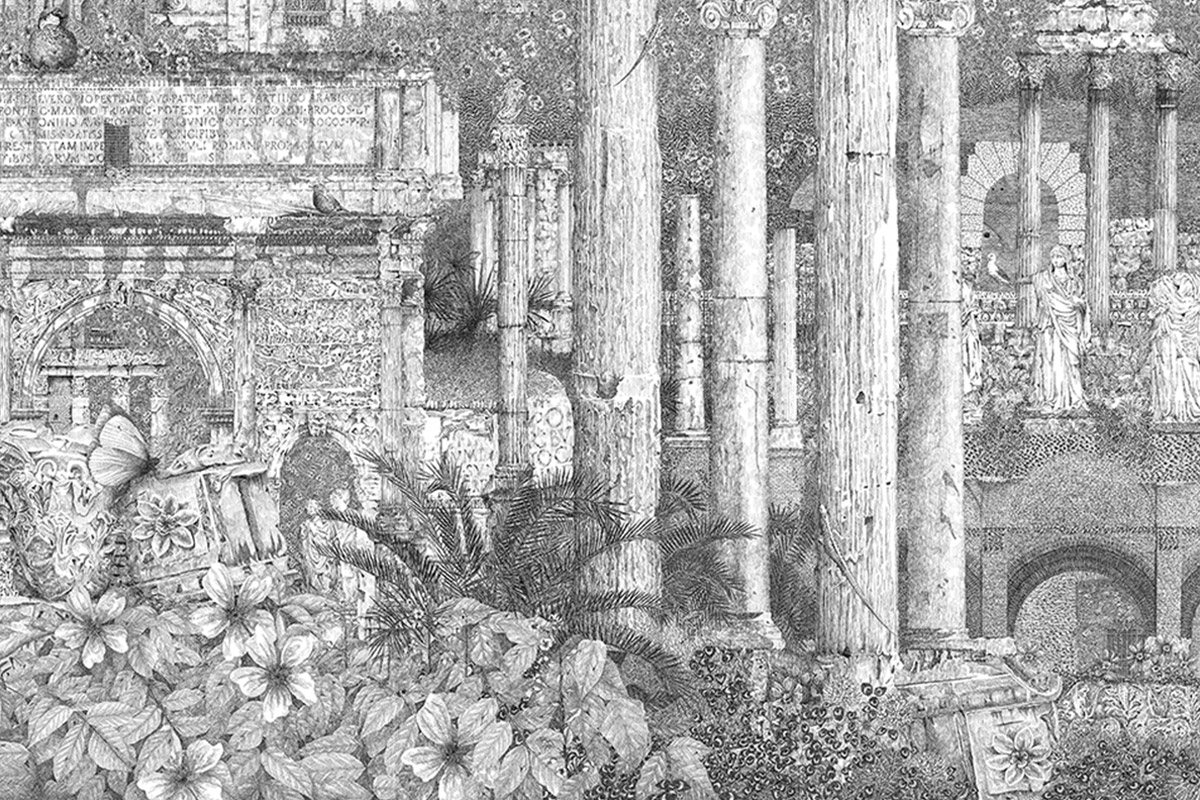

I draw. By hand, with ink on paper. I draw as part of my research, large, complex and time-consuming drawings (I can work on a drawing for several months), but I also enjoy sketching on site, taking time to observe how everything fits together. Drawing buildings and landscapes, whether existing or imagined ones, allows to bring forth enough character of place to appreciate what we are looking at, but leaves enough to the imagination so as to see in the drawing what it is we are hoping to find.

What is your approach on teaching architecture? How is the relation between theory and practice ?

There are many ways to begin a project, be it of design or research, but we must first ask a good question. Not so much about what is required by the project, but what it is we are trying to figure out with the help of the project. Just like we ask researchers how their work contributes to knowledge, I think we should ask how one’s architecture contributes to the world. That’s how I try to approach teaching: helping students figure out how to be designers who don’t take things for granted and who contribute something beyond yet again another building. In my teaching as in my own work, theory and practice go hand in hand, where a question finds answers through research and design, giving clues to each other on how to move forward. It is an iterative process in which one needs to be willing to engage with disciplines other than our own and willing to accept that we don’t always have a clear idea of where we’re heading.

Project 1

Finding Room in Beirut

Places of the Everyday

This project seeks to demonstrates why it is worth our while to explore the value and contemporary meaning of urban areas about to undergo complete renewal. Branching off from discourses surrounding the terrain vague, the project shows how large populated areas meet the criteria for the derelict and constitute a particular perspective from which to build a critical stance in regards to the contemporary city. But unlike terrains vagues, a vague urbain-an inhabited area where property ownership is obscure and informal behaviors a daily affair- possesses real communities an offers an alternative understanding on how a city can be practiced and lessons learned before its complete transformation. Stemming from a documentation of Bachoura, a central district of Beirut, Lebanon, the project shows how the vague urbain allows for different ways of inhabiting, ways that are as -or perhaps even more- real and anchored in the imagination of the city as those proposed by standardizing development. (Punctum Books, 2019)

Project 2