22/011

CHCC Kollektiv

Platform

Countryside / City

«If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions.»

«If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions.»

«If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions.»

«If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions.»

«If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions.»

Please, introduce yourself and your project…

We are Nina Krass and Susanna Böcherer and we started CHCC Kollektiv in the beginning of 2020 as a side project to our jobs in „traditional“ architecture offices. We both worked at the same big architecture firm and also studied together at the PBSA in Düsseldorf. We believe that in the field of architecture it’s possible to work in different ways at the same time and the theoretical work for CHCC was our critical outlet while realising buildings during the day job. Together with Studio Gross and c/o Now we recently founded aaaa, the Anti Architecture Architecture Association, to fight for a change in the German speaking architecture field. We also try to engage in multi-disciplinary projects and teaching at universities. Just recently we changed our jobs. Nina started as Customer Success Manager at Concular and Susanna began as research associate at the KIT (Karlsruher Institute of Technology.

Portrait – Nina Krass and Susanna Böcherer

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and the extended field of architecture theory?

We both grew up in rural parts of Germany in middle class families with us being the first/second generation of academics. The 90s and early 20s weren’t the most political years and we started our studies with a classic neoliberal mindset.

We both started out in interior architecture, but as the semesters passed the scale of our studio projects grew and we started to question the things we’ve been taught at university. The focus of our university work began to shift from aesthetical to social and political aspects. In the end both of us wrote our thesis about urban/spatial planning. We both loved engaging theoretically with the field and therefore approached our master studies more theoretically as well. Our background made unpaid internships in fancy offices impossible. To finance our studies we both worked in bigger companies from very early on. Once you’re in a certain line of work, it gets harder and harder to change direction. As it’s nearly impossible to earn a living by working in the theoretical field only and due to the economic crisis in the late 2000s we both took jobs in several traditional architecture practices.

Working in an architectural firm sharpened – and still shapes – our focus on values and what is going wrong in the industry. Although it’s quite frustrating sometimes we feel it’s important to ask questions and take a close look at current projects and developments. We felt that instead of solely complaining we should start writing about which problems our industry faces so we started documenting publicly through our Instagram account, and set up a homepage.

What comes to your mind when you think about your diploma project?

Although our diploma topics are set in completely different contexts, they have a lot in common. They both deal with places that are considered unappealing by most people. Moreover, the self-imposed task was not so much creating aesthetic architecture but to develop a functioning structure with people at the center. Susanna investigated how the rural exodus in small eastern German towns could be reversed by creating new structures and offerings. Nina’s master’s thesis deals with the West German large housing estate as a potential place for creating livable neighborhoods through re-densification. In general, we both knew by the end of our studies that for us architecture had nothing to do with facade design and perfect floor plans. Social and political aspects of urban planning were already more important to us, and this is also reflected in our work today. The idea that building anew isn’t necessarily the right solution in most cases is also an important facet of our understanding of architecture.

Until recently you were both employees in architecture offices, earning your living through this work. How did that shape your work while starting CHCC?

Working in the field while reflecting on it means we have firsthand experience, as we live and work through what is going wrong in the industry. We base a lot of our articles on said experience. Whether it’s specific building projects that due to a lack of political will are implemented by investors in a way that social and structural sustainability take a back seat in favor of the largest profit margin, or topics from everyday working life such as discrimination, exploitation and poor salaries.

The majority of (young) architects work in big practices with projects from questionable clients and little to no voice in the design process, which in return leaves them with a feeling of insignificance. Yet it is precisely the organization of employees, activism and unionising that provides the opportunity to change things on a large scale in bigger offices. Only by changing the big players in the industry, the whole industry might change. It became an important topic in our work with CHCC and that’s also why we’re still in the balancing act between commercial architecture and a more radical approach. We’re not sure though how much longer this will work out. More often than not it’s really frustrating as our own standards of architecture and those of a commercial architecture firm differ a lot. In addition, working in such patriarchal structures is very tiring.

CHCC is – so to speak – our outlet for all the anger that accumulates in the daily job and for projects that would never be pursued further in a profit-oriented company.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as a location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your work?

The places themselves don’t influence us that much, it’s more the fact that one of us lives in the biggest city in Germany and the other lives on the countryside. Life in both these places is very different and it is precisely where we draw insights for our work from. Things that work in Berlin don’t necessarily work in the Black Forest – and vice versa. Looking from both sides allows us to not get stuck in a bubble.

Funnily enough, this contrast was also the focus of our research during our studies. Redensification is important in urban and peripheral locations, the difference lies in its design and is not limited to additional GFA (BGF). We like to talk about social density: what is lacking to make a neighborhood feel livable and what kind of social and built density enables that?

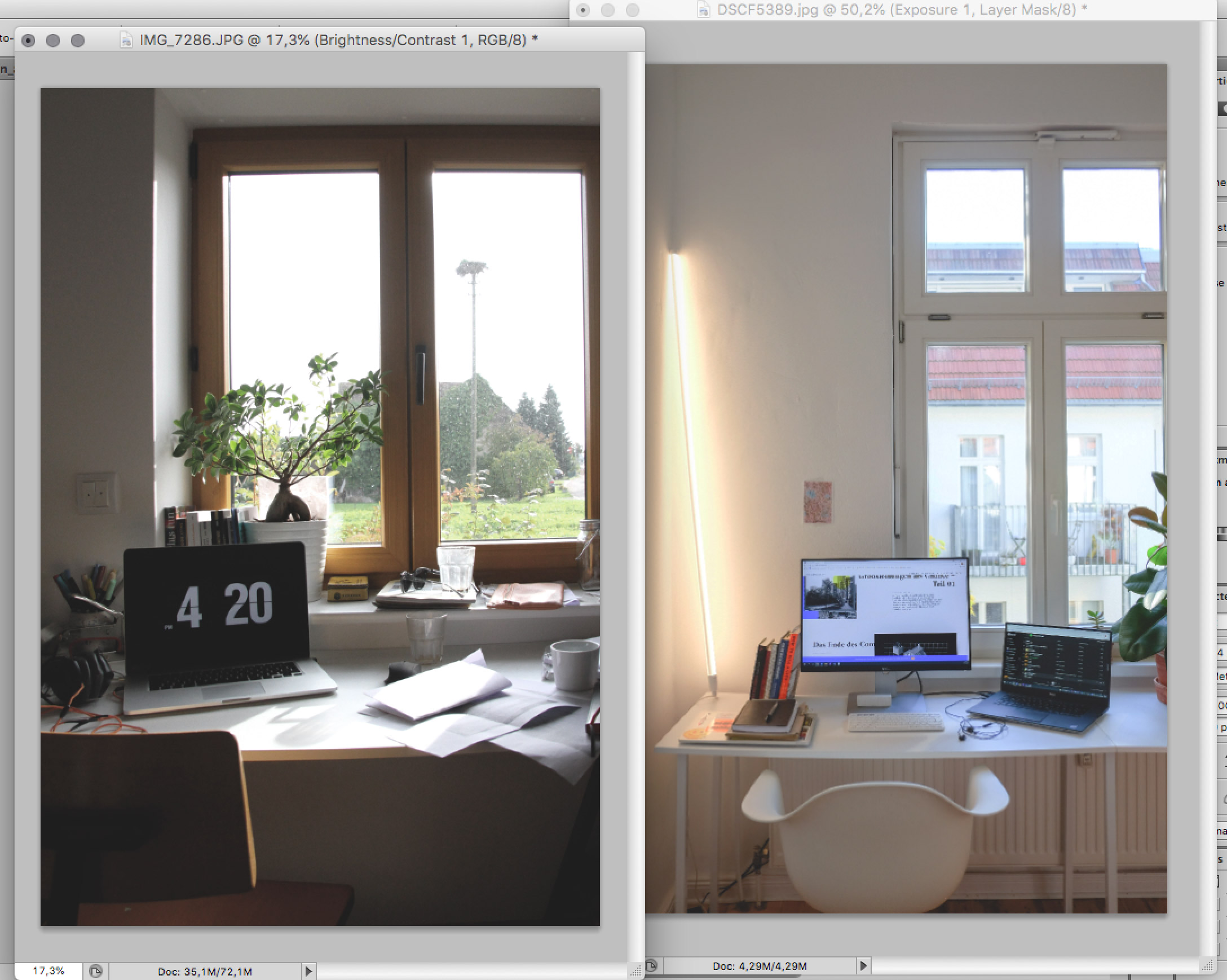

What does your desk/working space look like?

Digitally we are right next to each other

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

Architecture has an impact on every being on this planet, whether it’s the built environment we encounter daily or the environmental impact by the materials and emissions of the building itself. This is what it comes down to. The bird in the sky doesn’t care about pretty facades, but we owe it to this creature to leave space for it to build his nest. The kid in the sketchy neighborhood doesn’t care about pretty facades, but she needs a library, a school, access to public transportation and an affordable home for her family. However, architecture does not necessarily require architects. We as architects are not as important as we would like to be. If we understand this at some point, it may finally be possible to bring together expectations and reality in our profession.

Whom would you call your mentor?

Nina: I think who influenced me most is Jörg Leeser (one half of the founders of BeL) who supervised my master thesis and for whom I worked later as an assistant. He was advocating that architecture doesn’t consist of pretty facades but humans, dirt, and chaos and all the beauty behind it. This shaped my whole attitude as an architect more than anything else.

Susanna: I don’t think I can name a mentor as much as people whose work and opinions had a tremendous impact on my life. I was inspired by Nina’s ability to question the status quo and expand one’s knowledge by learning from many different authors by leaving the beaten path in academia.

Name your favorite…

Book:

Nina: Lately I really enjoy most books from Paul Mason and Thomas Piketty.

Susanna: ‘Arrival city’ by Doug Sanders changed a lot for me. It made me realize how integral politics and policies are for our cities. I often pick up ‘Der Glaube an das Große in der Architektur der Moderne’ by Sonja Hnilica to remind myself of the possibilities.

Person:

Only as a group of people one can change the world and @Dank.Lloyd.Wright are working hard on doing so.

Building:

Nina: A formative experience for me was living inside Münsterpark in Düsseldorf, a brutalist large housing project designed by Walther Brune and built between 1971–77. This house taught me what quality in housing on a large-scale means.

Susanna: A friend of mine lives in a Baugruppe in Nürnberg. The complex consists of existing buildings and an unpretentious addition in a backyard. The former chocolate factory is a great example of how small-scale, well thought-out, and sustainable architecture can improve the life of the inhabitants every day. When my friend moved there, it made me realize just how crazy the whole starcitecture really is, since buildings like that have a way bigger impact on actual humans, the environment and neighborhoods.

How do you communicate architecture? Why did you decide to use this specific way of communicating/presenting architecture?

Architecture has become a product of the internet age with short attention spans and the constant, uncritical urge to create something new. Even as a student, one learns that it is sufficient to design only on paper or digitally to get attention and to publish designs. But promising renderings and buzzwords are rarely political, activist, or bold. And it is not enough to reproduce apparent solutions in impromptu designs without addressing the actual political and social conditions.

Yet we use Instagram or social media in general to communicate our work. We want our work to initiate discussions. We want to change the status quo. And that is only possible if you interact with peers, form alliances and then initiate change. We do not want to communicate solely within the architect bubble, rather the opposite. Interdisciplinary collaboration is inevitable for the future of our profession. And that simply works best via social media.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

The era of the great planners who designed all-encompassing ideas for our cities is over. With current issues in an ever-changing world (such as climate change, political instability, and inequality), the previous generations of architects can only be a limited role model for us. Yet they are still shaping the future of our cities. This has to change!

We are amid a global process of change, socially as well as economically and ecologically. In our opinion, the architecture industry is reacting far too sluggishly to these changes, especially due to its close ties with politics and capital.

Hero worship, technocracy and elitism still dominate the profession. But for the younger generation of architects, the pinnacle of creativity no longer lies in building the most extraordinarily shaped office towers, museums or opera houses possible, clad in exciting facades. We have recognized that architecture can only survive through a multidisciplinary approach. But looking beyond the horizon to social, political or economic issues rarely takes place at universities or in offices. It is becoming increasingly clear that the profession of the classical architect is about to become obsolete if the discipline does not change. Drawing work is being taken over more and more by computer programs, making fewer planners necessary. Buildings are increasingly executed by general contractors. Construction tasks are also fundamentally changing – new construction will become less common due to space and resource constraints. Intelligent solutions for conversion and refurbishment, on the other hand, are gaining importance.

We firmly believe that the future will hold a lot more interdisciplinary work. Urban planning is a lived reality. Architecture must shed its claim to validity and develop a healthy pragmatism in the development of the city. In short, there must be a comprehensive rethinking in teaching, the profession itself as much as in politics.

There is much to do – but change is possible and inevitable, because the luxury of choice is no longer available to younger generations. Architecture cannot solve the pressing problems because their causes lie in structures far beyond our field. But change does not come from uncritical adaptation to those, and answers must be found anyway.

What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

In Germany, architecture and the building industry are omnipresent, but architects themselves do not play a role in any discussion of pressing issues such as housing shortages or sustainability. For many years, there was no separate ministry of construction (Bauministerium), which demonstrates just where the priorities lie in Germany. For decades, politicians have relied on investors and private actors without acting themselves. We as architects have always been accomplices of this policy and the exploitative, capitalist system that makes the production of space possible. The fact is: building, and at best bringing about social change through architecture, is incredibly difficult.

However, the architecture industry has a hard time creating innovative solutions beyond superficial design. In our opinion, this is mainly due to the lack of will to question our role combined with the elitist mindset of our profession. The Covid-19 pandemic was a great example: The world stopped and in a short time we were confronted with a number of proposed solutions to the lockdown problems. The multitude of competitions and designs launched shortly after the pandemic began were a perfect example for "building in the bubble”.

Instead of addressing the long-term impact of a global pandemic on our society, they proclaimed the perfect home office, the fanciest protective suit, or rethinking offices based on prevailing no-contact laws. These designs were mostly within the architectural profession and possessed a certain superficiality. Design can solve all our problems, whether pandemic or climate change – this was the basic message.

Architecture critic Kate Wagner coined the term “PR-chitecture” when discussing designs to overcome the pandemic. The result is mostly disappointing:

“Most of the time, PR-chitecture results in disappointment. Sadly, homelessness, a social and political problem, can not be solved with 3D-printed tiny houses. Sadly, glitzy co-living dorm mockups could not solve generational and income-based housing disparities, a social and political problem. Sadly, shiny renderings of solar-paneled floating cities sponsored by an ex-MIT Media Lab startup will not solve or mitigate the effects of climate change, a social and political problem.”

The instagrammable visuals of starchitect offices shield the work of smaller, less flashy firms working on real-world solutions to problems like sustainability without green facades, affordable housing or equitable neighborhood development from public view.

If architecture is not to become obsolete as a profession, we have to become more political, show more backbone and also get involved in cross-industry discussions. And finally realize that you can’t save the world with design alone.

How do you understand the relation of theory and practice in architecture?

In our opinion, theory and practice are worlds apart. Here, too, the basic problem already lies in universities. Architectural theory, if it is taught at all, deals exclusively with topics from the past and always only within the profession. Dealing with current issues and with social and political sciences rarely takes place. It seems that architectural theory is even more elitist than the building faction. In the German-speaking world, it is always the same actors who have their say in publications. Without a doctorate and a professorship, hardly anyone has a chance of being published.

The practicing faction, on the other hand, only deals with theory when it benefits the marketing of their own designs. Most of the time it remains with superficial phrases about ecological and social sustainability to sell projects through greenwashing.

It sometimes feels like architecture has lost touch with reality. We need to get out of our elitist bubble and into the uncomfortable reality that has nothing to do with glossy renderings.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

The critical questioning of things that are sold to you in your studies as if they were the only truth. Whether it’s the sole focus on the Western, white architectural canon, the cult of personality around certain (white male) architects (Le Corbusier and Johnson, looking – not only – at you) or the toxic work culture that is drummed into you.

In the worst case, young architects reproduce the outdated patterns of their teachers when they start with a completely unrealistic idea of everyday life in an architectural practice. Overtime, weekend work, low salaries – all problems of a neoliberal system, which is still reality in many offices today and is stylized and paid homage to at universities.

For people from outside the industry it seems so outdated, but not for architects: they are taught during their studies that good architecture can only be created with blood, sweat and tears. Night shifts and working to complete exhaustion are celebrated and recognized. This practice forms the perfect basis for easy exploitable graduate supply for the offices. Those who persevere long enough have internalized these patterns to such an extent that they are passed onto the next generation since the bad working conditions are accepted as an irrefutable truth and are not further questioned or changed. It’s a vicious circle.

How do you perceive yourself as a female architect working in a male dominated field?

Face it – architecture is a very conservative and white male-dominated business. But as white women we’re already privileged. Feminism should not focus on empty liberal ideas of white CEOs and girl bosses. Feminism has to be intersectional because if it’s not, it’s just reproducing the same patriarchal patterns and comes at the expense of marginalized groups. Therefore we cannot think of feminism without reflecting on racism, capitalism, imperialism, and the patriarchy.

Still, we face challenges nearly every day. In a male-dominated field, one has to prove oneself in every new project, every new (male) person you meet. Both of us have been called annoying or irrational by male colleagues whenever we speak up about equal rights and the implementation in our daily business. We found out that it helps to look for allies and mentors. Female-read individuals need to encourage each other and break down patriarchal structures. Too often toxic patterns of the male-dominated industry are also adopted by (white) women. We always have to be aware of not falling into that same trap. We have to be promoting and supporting marginalized groups of people. We feel obligated to stand up for less visible individuals because we have a position, which enables us to do so.

It’s so refreshing to see how it can be different. Nina has been working on a big project where almost all planners are women. Feeling the changed dynamic in an all-female team is great, all team members are open and supportive, no one needs to push their ego and it’s all about how to implement the project hands-on.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

We think the way we can use social media to find allies all over the world is such an exciting change. You can use instagram to learn about important social issues, all you have to do is follow the right channels. To just name a few: @aaaa__arch, @ifa_diaspora, Kate Wagner over @mcmansionhell and @fa.front.

Focus

CCHC

We are working on many different projects and therefore it is very difficult to pick out single aspects. Therefore we have made a big graphic that shows what we are working on and what our main focus is.

Website: chcc-kollektiv.de

Instagram: @chcc_kollektiv

Facebook: @CHCC-Kollektiv

Photo Credits: CHCC Kollektiv

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 05/2022