23/010

Common Agency

Architectural Practice

Berlin / Hamburg / Cologne

«The first question to ask is no longer ‹How does the building look?›, but ‹How is it financed?›»

«The first question to ask is no longer ‹How does the building look?›, but ‹How is it financed?›»

«The first question to ask is no longer ‹How does the building look?›, but ‹How is it financed?›»

«The first question to ask is no longer ‹How does the building look?›, but ‹How is it financed?›»

«The first question to ask is no longer ‹How does the building look?›, but ‹How is it financed?›»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

Common Agency was founded by us – Hans von Bülow, Cornelius Voss and Julian Meisen – in 2019. We had met ten years earlier, during our first day at University of the Arts Berlin (UdK). On that day we walked into the building at the exact same moment and have been friends ever since. Today, we are working together on various projects at various scales. We are driven by our shared belief that we can realise better projects, if we actively seek out places to be conceived, buildings to be built and objects to be designed. That is why we start our projects by exploring new ways of space production, thereby enabling more progressive designs, more democratic spaces, and more sustainable constructions. Besides all the things we share, we are also quite different in character and abilities, and we work across three different cities: Hamburg, Cologne, and Berlin. We feel that we complement each other quite well, which turns out to be a great advantage for our ambition to not only act as architects, but also more holistically as space producers.

Portrait Common Agency – Julian Meisen, Hans von Bülow, Cornelius Voss– © Christoph Mack

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

Speaking of complementary abilities, the fact that we met in architecture school, proves that architecture can be a melting pot for diverse interests, as it really is the intersection of our individual interests. Each of us tends to approach architecture from one of three different angles: Whereas Hans is looking at architecture very much from an artistic perspective, Cornelius seeks to combine his architecture background with his passion for entrepreneurship, Julian is driven by finding ways to translate his interest in theory and architectural discourse into the built environment.

Already during our studies at UdK Berlin, we started to ask ourselves how to combine those interests to formulate a new approach towards establishing a young architecture practice. Analysing the traditional structures of the discipline, it appeared to us, that we should invest our time in finding ways to become more independent and autonomous as architects. Hence, our goal became not to rely on conventional ways of filling the practice’s project pipeline, such as public competitions or commissions by private individuals or real estate companies. Instead, we have aimed at initiating projects ourselves.

The architect’s transformation into a fully-fledged space producer became our goal. To fulfil this ambition we had to develop several additional skills. That’s why, after having worked for architectures offices, we all quit our jobs and started to work for design agencies and real estate developers. This background strongly informs the way we work today. This is how the concept of agency – the capacity to act fully self-determined – became the essence of our vision for the profession: An evolution towards a greater common agency.

What are your experiences founding your own practice?

We had been talking about starting our own practice before we worked together on a project for the first time. In 2018, we teamed up with betahaus Hamburg to develop a pitch for the revitalization of Hamburg-Altona’s former tax office. This had been prompted by a call for concepts by the city of Hamburg.

Cornelius - who is based in Hamburg - heard about the opportunity first and discussed its potential with Robert Beddies, Head of betahaus Hamburg, a local co-working space. Soon, an idea was born: We proposed to create a cooperative for the sole purpose of turning Altona’s former Finanzamt into Neues Amt Altona. The central idea was to combine the concepts of collaborative work with cooperative financing and a design that centres the needs of its future users. Furthermore, the cooperative would be able to raise funds to finance the extension of the existing structure which would create a new work environment for the cooperatives’ members. Most importantly, we conceived a project without equity capital but solely an idea.

After three very intense weeks, we had finished the concept and submitted it at the very last minute. It took half a year until we heard back from the city. We almost forgot about our pitch and neither of us dared to imagine that our proposal might be chosen. However, it was. In this moment, not only Neues Amt Altona was born, but Common Agency also. Today, as Neues Amt Altona is approaching construction, we are delighted that our very first project can be taken as an accurate illustration of how our theoretical approach can be translated into physical reality. So really, our practice was founded with a vision, but also a good portion of naivety and spontaneity – probably a good combination.

What is the essence of architecture for you as a group?

There are many answers to this question and they are all somewhat relevant. For us, all those interpretations of architecture’s essence are deeply dependent on the preconditions in which architecture unfolds. Our understanding of architecture begins – independently of its physical appearance – with the socio-economic condition in which it is conceived and realised. Regarding the poor quality of contemporary urban development, we believe that our profession can no longer ignore its tragic dependence on forces it cannot control. When it comes to our understanding of architecture’s essence, the first question to ask is no longer “How does the building look?”, but “How is it financed?”. We believe that there are plenty of talented architects out there, but very few get the chance of using their true potential. Unleashing this potential, by creating new structures for architecture to develop, is our starting point.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you?

In an ideal world, there are only great clients: Within the public sphere architecture commissions are guided by culture and debate. Within the private sphere, clients are individuals who care about architecture and feel responsible for their buildings and its social context. Perhaps there were times when this was the case. However, we all know, this world does not exist currently and is unlikely to come into existence anytime soon. Hence, we must find alternatives ways of improving the architectural quality of urban spaces by applying pressure on the public sphere. We want to strengthen the alliance between politics and all those new, progressive space producers that are emerging everywhere.

Collective initiatives from the cooperative world, self-organised “Baugruppen”, as well as new “developers” from the field of architecture, urbanism and political activism seem most likely to address the most pressing issues of our time, such as climate change or social justice.

Of course, this only works with political support. That means we need more public land to be provided for leasehold and more conceptual tenders to foster public-civic partnerships. Currently, there are only a handful projects in this category. So the question really is: How can we turn this into a mass phenomenon?

Furthermore, the new space makers have to professionalise even further. We believe that architects have to start to engage more pro-actively in this journey, which requires an additional set of skills. We believe that those skills – such as legal and financial acumen – need to be further integrated into the university curriculum. We must raise awareness amongst students that they will have a very limited agency as professionals unless they engage in establishing new structures.

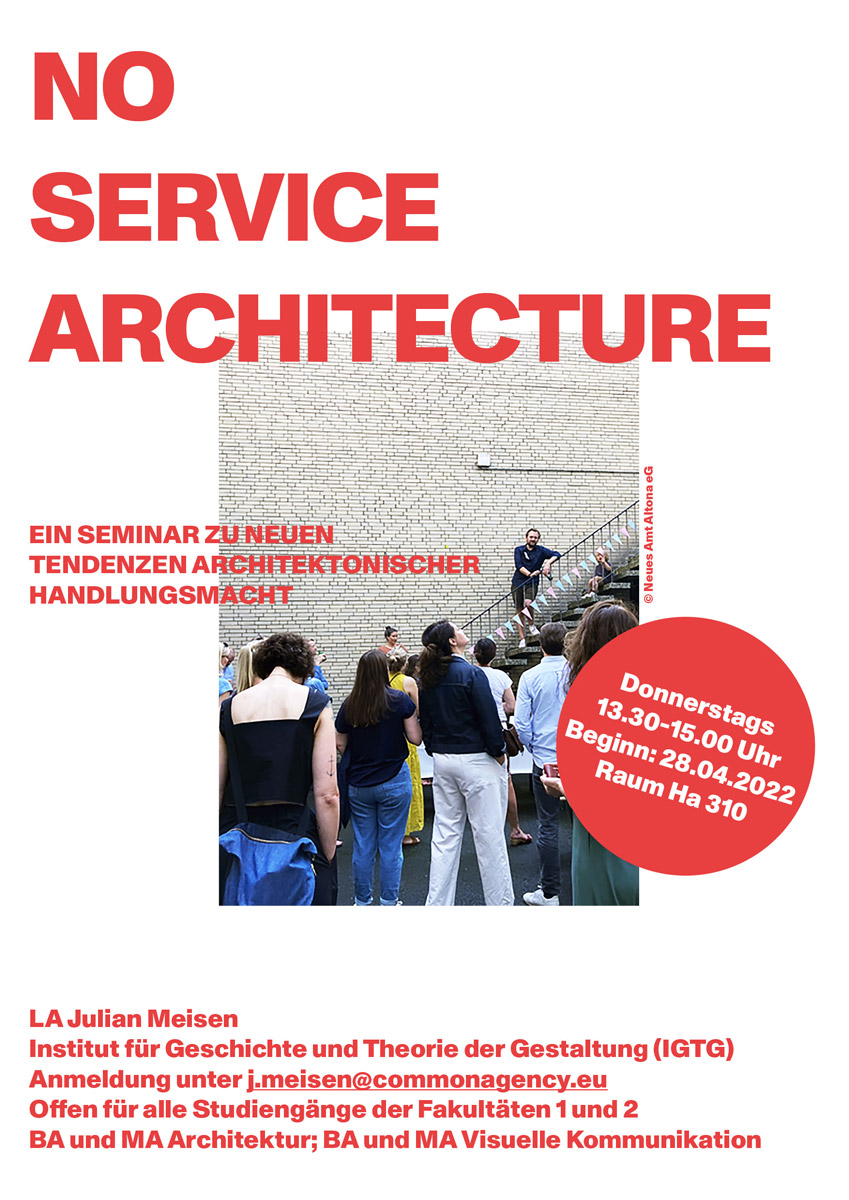

That is why Julian gave a seminar on this issue at UdK Berlin called „No Service Architecture“. The seminar questioned whether architects create better buildings for all of us, when they build for themselves and eventually overcome their traditional role as service providers and it was based on the observation that many of the most acclaimed projects, which have been realised in Germany within the recent years, fall into this category. Examples include Wohnregal by FAR frohn&rojas, several projects realised by Arno Brandlhuber and his team, Frizz23 by Deadline Architects, Eckertstraße 1 by Orange Architekten and even huge public-civic partnership projects such as Haus der Statistik. The seminar visited a number of those projects. We met their protagonists and analysed the economic and architectural strategies behind them. We believe that there is much to learn from this kind of space production.

Another central idea is to reinterpret the ongoing housing crisis as an opportunity to reinvent the generic. There are many reasons to believe that we can only satisfy the urgent demand for affordable housing through systemisation. Let’s take all the limitations we currently work under – time pressure, rising costs and interest rates, as well as CO2 reduction – as motivation to reformulate the economy of construction. Recent projects have demonstrated that prefabricated, systemised architecture can be quick, cheap, low carbon while also meeting high aesthetic standards. A good generic architecture so-to-speak, almost evoking a modernist spirit through its synergy of economy, construction methods and design.

Poster "No Service Architecture" – Seminar at UDK Berlin 2022

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Of course, it is extremely important to have an excellent command of all the skills, which are traditionally at the core of conventional architecture education. However, as mentioned, we believe that the economic and legal aspects of architecture are extremely important, because they can help you realise what you have learned. It is very difficult to fulfil idealistic aspirations within the current structures of the building industry. Therefore, we recommend analysing the world at university into which you, as a young architect, will be released after university.

Whom would you call your mentor? What are your most important influences?

Rather than being influenced by mentors we are inspired by certain eras and movements which are still relevant today:

Among pre-modernist architecture, for us the French Neoclassical and Revolutionary Architecture is a very inspiring period. Whereas Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s daring designs first showed how form and program can be playfully combined within a meaningful unity, Jean-Nicolas-Luis Durand’s normcore feels especially contemporary. This is especially true currently, given the focus on rational forms of construction as a tool for spatial empowerment.

Furthermore, the utopian ideas of Japanese Metabolism are increasingly becoming realisable. Today, modularity and adaptability - supported by digital fabrication - are again core concepts of progressive design strategies – however freed of the weight of cultural meaning and the aura of a nation that is rebuilding itself. Do we need an alternative narrative for contemporary neo-metabolism?

From Buckminster Fuller, to Superstudio and the Whole Earth Catalogue: The architectural expression of Hippie Modernism and counterculture and its ultimate liberation of form and program strongly influenced our vision of holistically designed spaces.

Also, we are fascinated by OMA’s work in the late 80s and 90s, after Rem Koolhaas turned away from Postmodernism – another liberating moment for architecture. In the lobby of OMA’s Rotterdam office, the model of the Très Grand Bibliothèque (TGB) project used to welcome visitors – with good reason we find: Projects like the TGB or Seattle Library introduced the spirit of all-encompassing sculptures of social forces to the architectural discourse. They created an aesthetic world of their own, which could not any longer be judged by conventional standards.

Books:

Anthony Vidler: Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. Architecture and Utopia in the Era of the French Revolution, 1988.

Rem Koolhaas & Hans Ullrich Obrist: Project Japan – Metabolism Talks, 2011.

Andrew Blauvelt: Hippie Modernism – The Struggle for Utopia, 2016

Holger Schurk: Project Without Form. OMA, Rem Koolhaas, and the Laboratory of 1989, 2021.

What does your working space and your building sites look like at the moment?

Working Space – Berlin

What is your favorite Material?

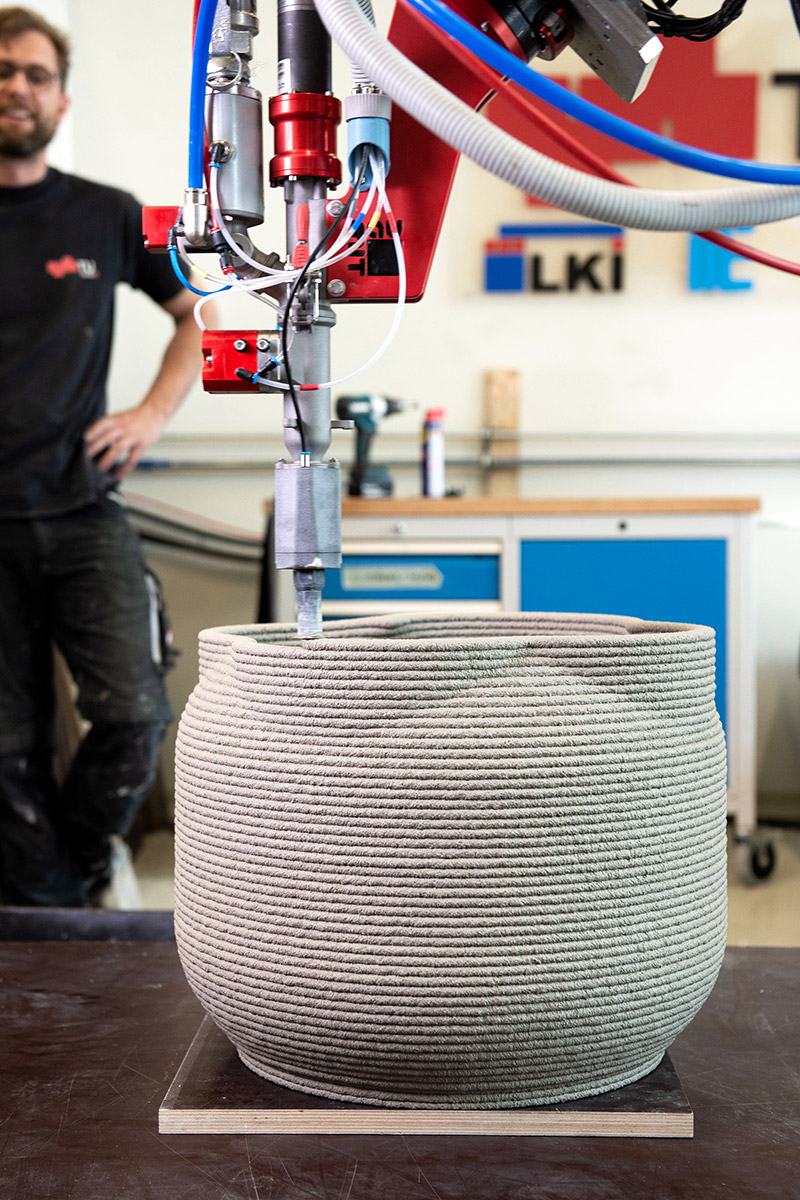

We do not have a favourite material, but we are especially interested in integrating traditional building materials, such as wood, stone or straw within contemporary aesthetics. We are always looking for opportunities to test these materials. Furthermore, we are currently delving into the world of 3D-printing of concrete and rammed earth which we are very excited about.

Although we are aware that we cannot exclusively rely on timber, we still believe in the potential of increasing the amount of timber construction in order to reduce the overall CO2 emission of our projects. For this reason, we often design buildings in timber modular construction, such as our winning proposal for the Lightywood competition. This project is almost entirely constructed with the aid of timber modules and will be one of the largest examples of this construction method upon completion.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

This is another reason, why we believe that architects have to find new ways to act more autonomously: it facilitates innovation and experimentation. Take Neues Amt for example, which is approaching construction. The building will have several features, which make it very sustainable: It is mainly constructed in wood, it will have an extensive green façade and it is radically low-tech – there is only heating and no air conditioning or ventilation, which is very unusual for an office building. We believe that only the specific structure of the project allowed us to go so far, as the decision for a low-tech building is the result of a participatory process. It might not be possible to work inside the building during the hottest days of the summer, which is a real concession to the users’ comfort.

However, the members of the Neues Amt Altona cooperative jointly agreed, that we can’t fight climate change by adding even more environmentally damaging technologies to our buildings, and voted in favour of a low-tech solution. Here’s a big advantage of projects like Neues Amt: We already know the building’s future users and we can just ask them what they want. That is rarely the case with conventional office developments, which, for this reason, must fulfil certain general standards and certifications. As the building will not be sold after completion, we don’t have consider certification to the same extent. Therefore we are free to experiment with more sustainable strategies.

We would like to add that it is so important to construct buildings which can be enjoyed for their aesthetic qualities. We mostly talk about grey energy of existing buildings, but we should not forget about future grey energy. That means: If we allow ourselves to build new, we should be especially careful that new buildings are adaptable in the long term and sufficiently beautiful to be appreciated and maintained by people, ideally even protected at some point. Perhaps preservation is the ultimate form of sustainability.

Project 1

Neues Amt Altona

Hamburg

2019 – 2025

Neues Amt Altona (NAA) is a development project located in Hamburg-Altona. It encompasses the construction of a new building, the protection of an existing, affordable creative hub, as well as the formation of a cooperative-based community. Initiated by Common Agency and betahaus Hamburg, the project is dedicated to establishing a progressive and collaborative workspace within a socially and ecologically sustainable framework. The project will be co-owned by its users and rooted within its neighbourhood.

After holding a conceptual tender in 2018, Hamburg’s state-owned real estate company LIG chose the concept “Neues Amt Altona” conceived by Common Agency and betahaus Hamburg. Two years later, the Neues Amt Altona-cooperative was founded, and the new building is slated for completion in 2024. Currently, Neues Amt Altona eG has around 180 members and has raised €1.5 million in collective equity.

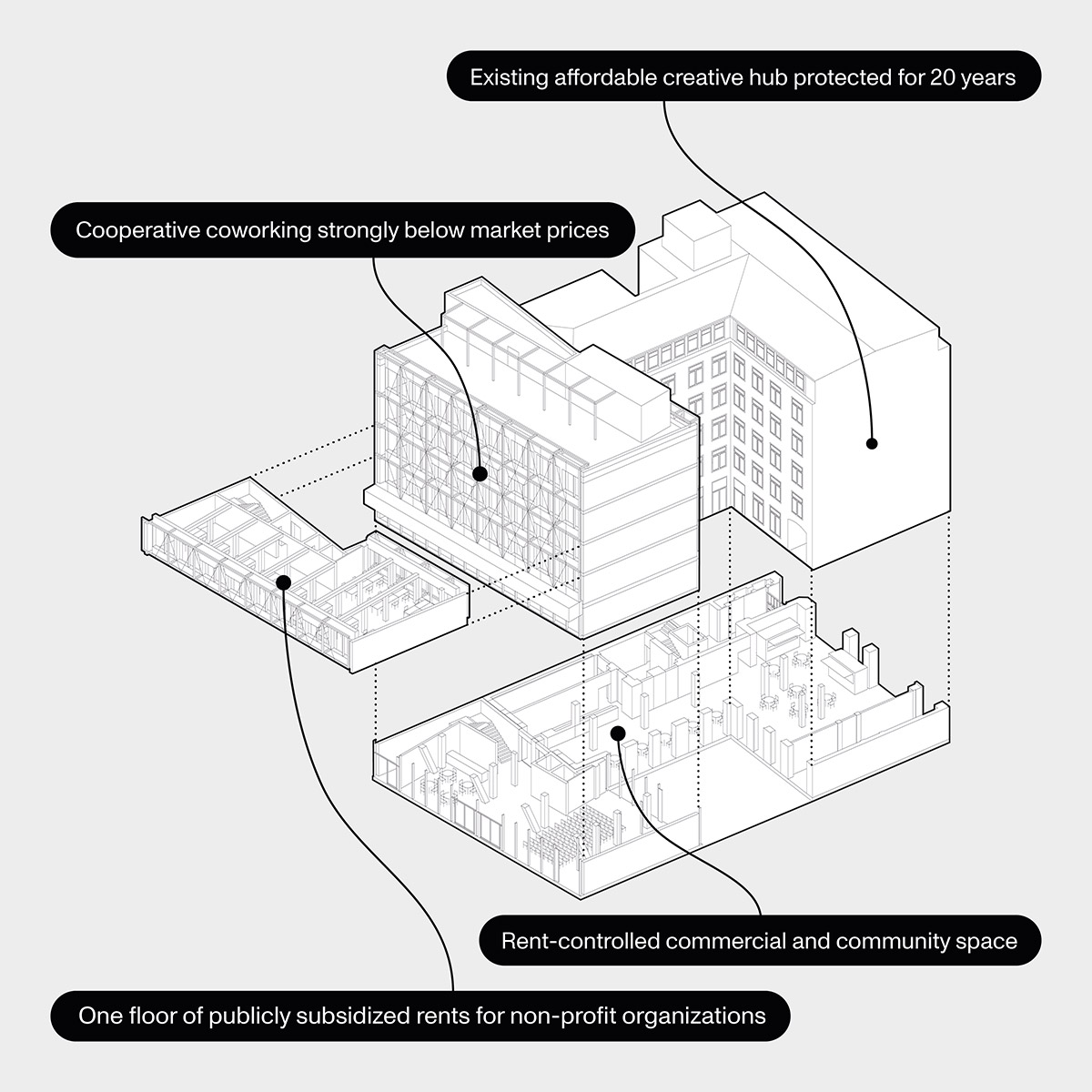

The project is located at the heart of Hamburg-Altona and will preserve Altona’s former tax office as an affordable hub for local creatives by controlling all existing rents for a minimum of twenty years. An extension of the existing building will create new coworking space for the Neues Amt Altona cooperative and a strong presence on Altona’s main street, Neue Große Bergstraße. While its roof will serve as a public recreation zone, the ground floor of both the existing and the new building will create a new public connection between both sides of the urban block. This will offer public and inclusive uses to the neighbourhood.

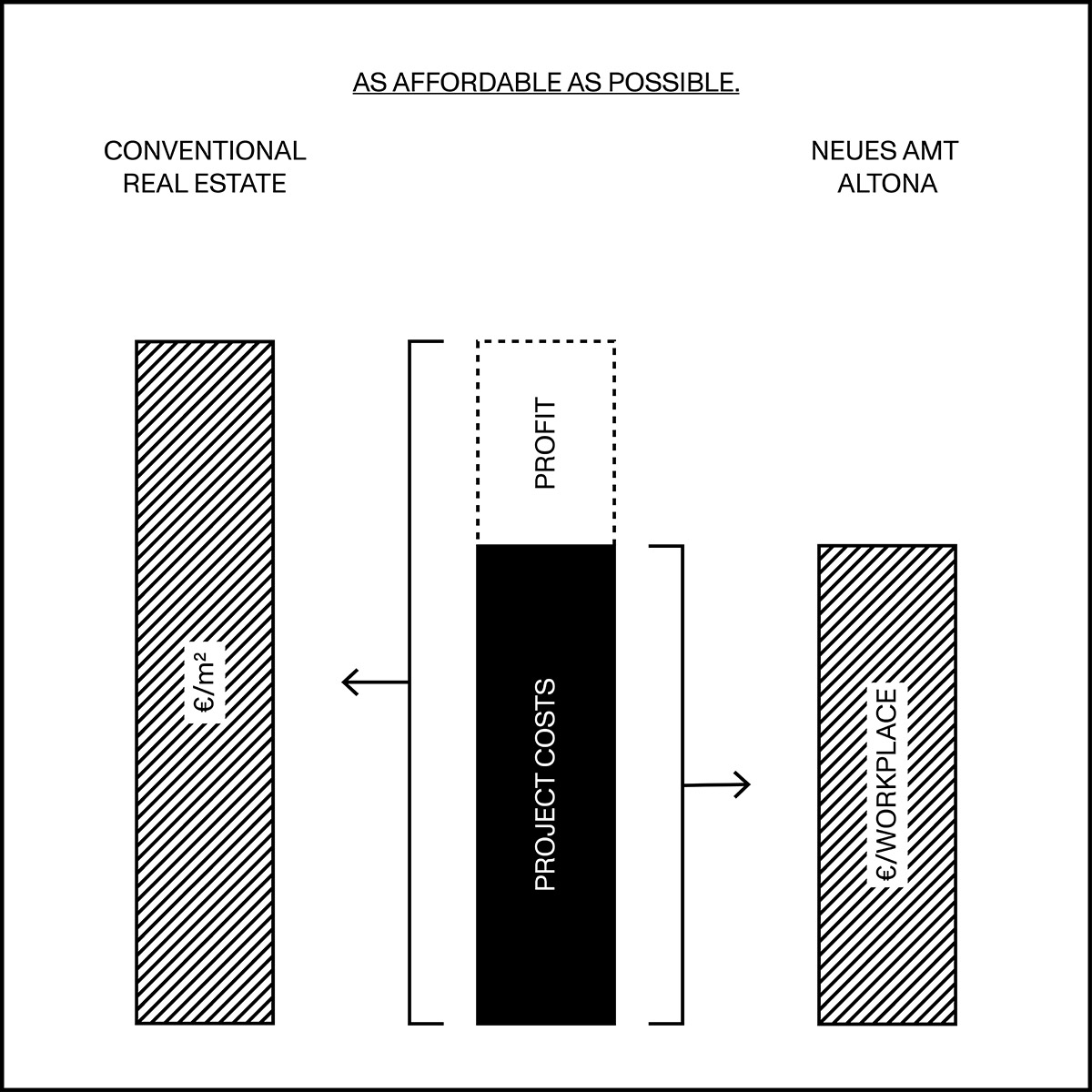

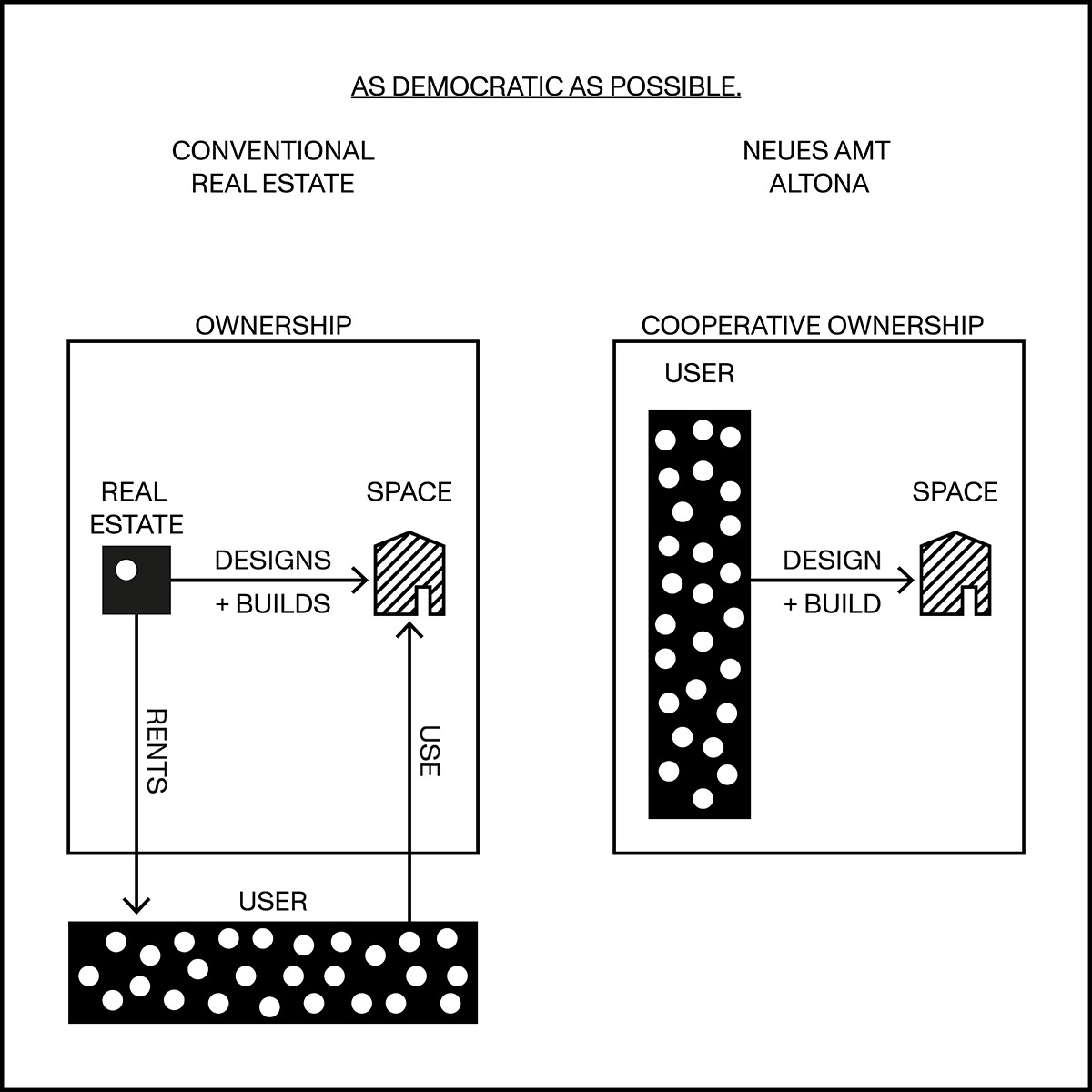

The cooperative model of the project allows its future users – local entrepreneurs and creatives – to co-own their workspaces at below market rates. What makes NAA special is that members of the cooperative do not acquire the right to use a certain number of square meters, but rather a certain number of workplaces, which are serviced by a coworking provider. The cooperative prevents the building’s commodification by profit driven real estate speculation for the duration of its existence. Furthermore, it promotes inclusion by opening the ground floor to the public and making a quarter of the total office space available to non-profit organizations at very low cost with the financial support of the city.

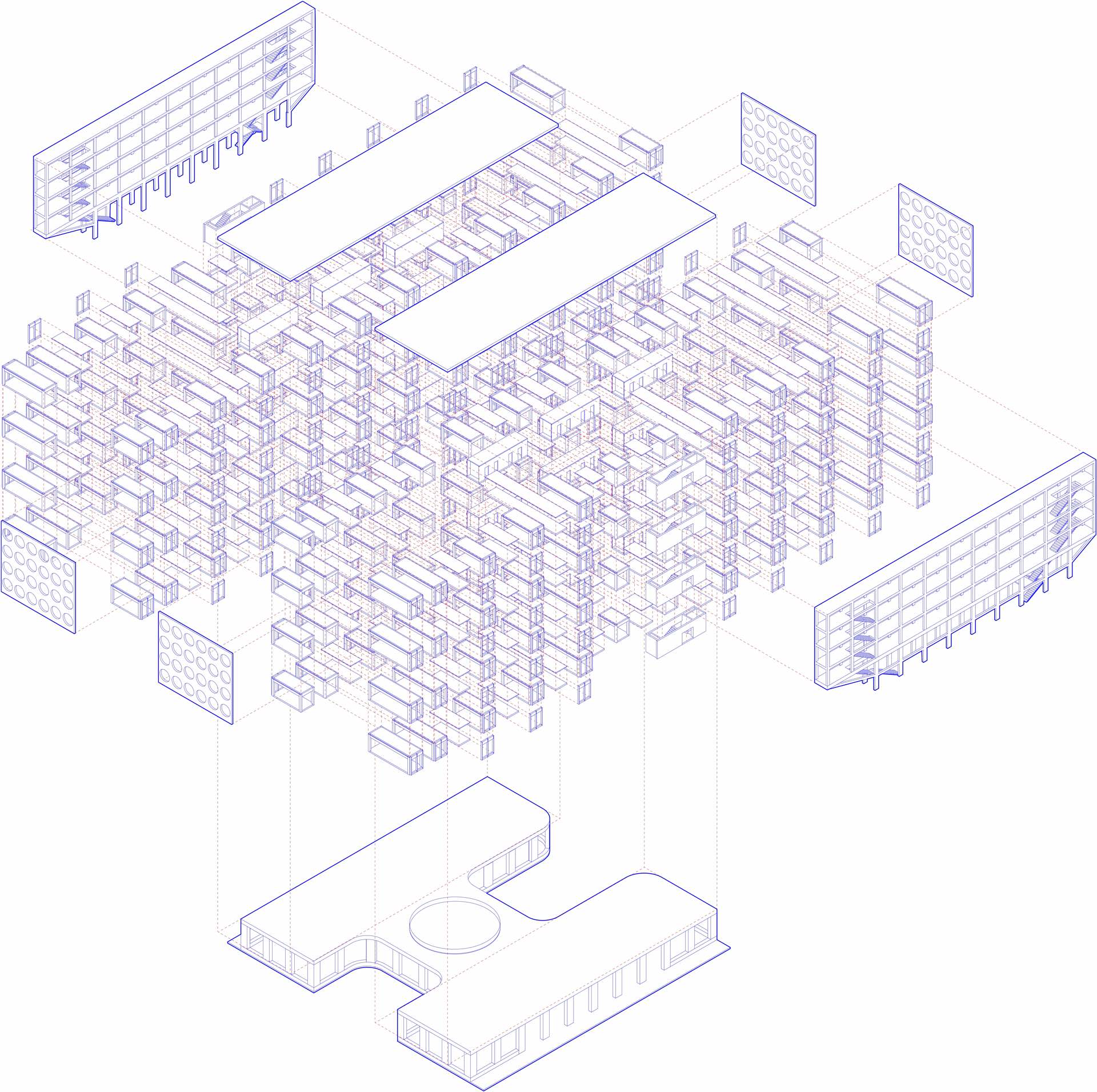

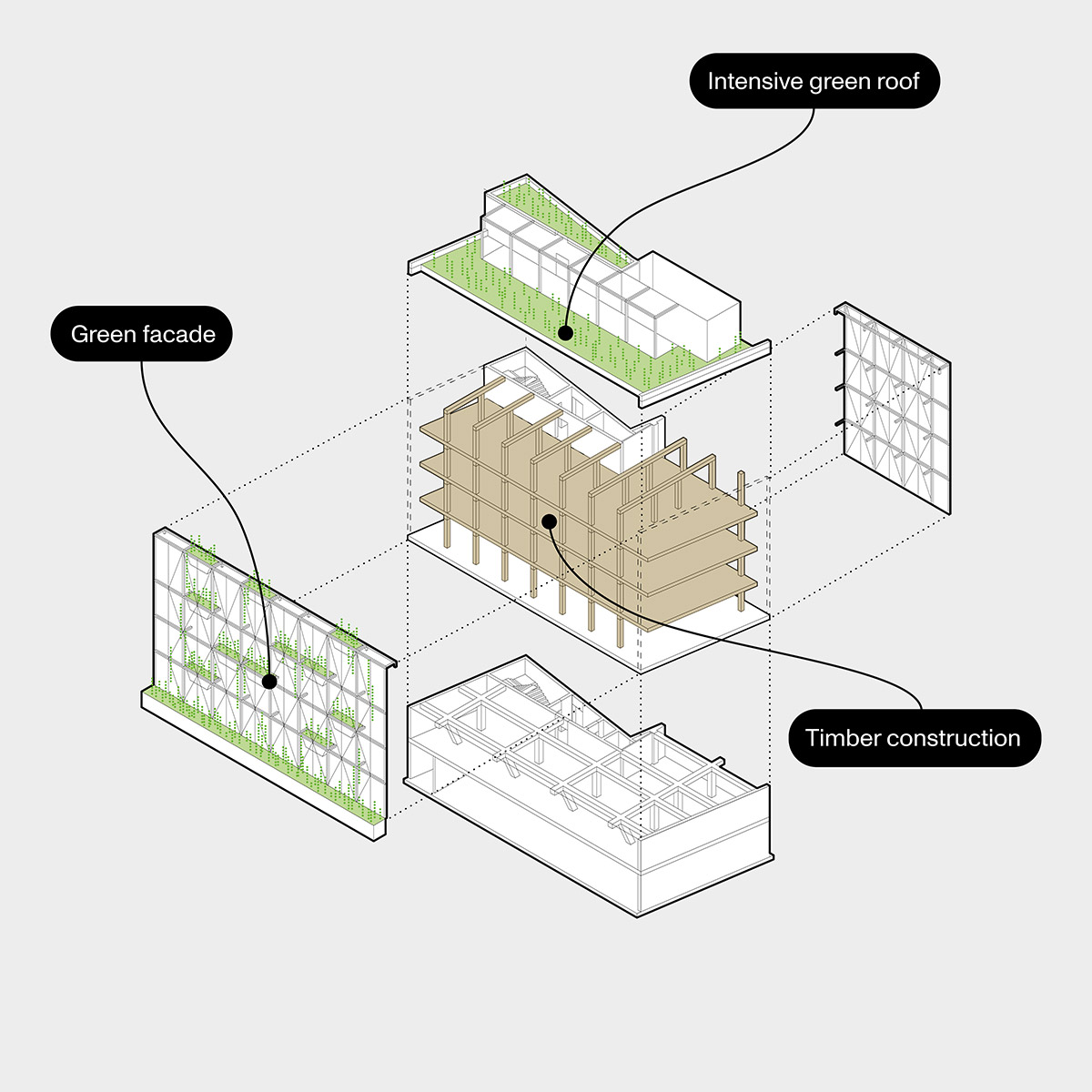

The new building is designed to allow maximum flexibility in spatial configurations for both the co-working zones on the upper floors and the public spaces on the ground floor. This will facilitate the long-term development perspective of the cooperative. While the ground floor is realised in reinforced concrete, creating a robust environment for its public use, the timber construction of the upper floors produces a pleasant indoor climate and drastically reduces the building’s CO₂ emissions during the construction process. NAA’s low-tech approach minimises built-in technologies and reduces operational energy consumption. In a participatory process, the cooperative members decided to forego a comfortable indoor climate during the hottest days of the year to realise a more sustainable building. Also, its extensive green façade creates a second layer, reducing the heat input, creating outdoor space on each floor, and adding a green habitat to Altona’s city centre.

Project 2

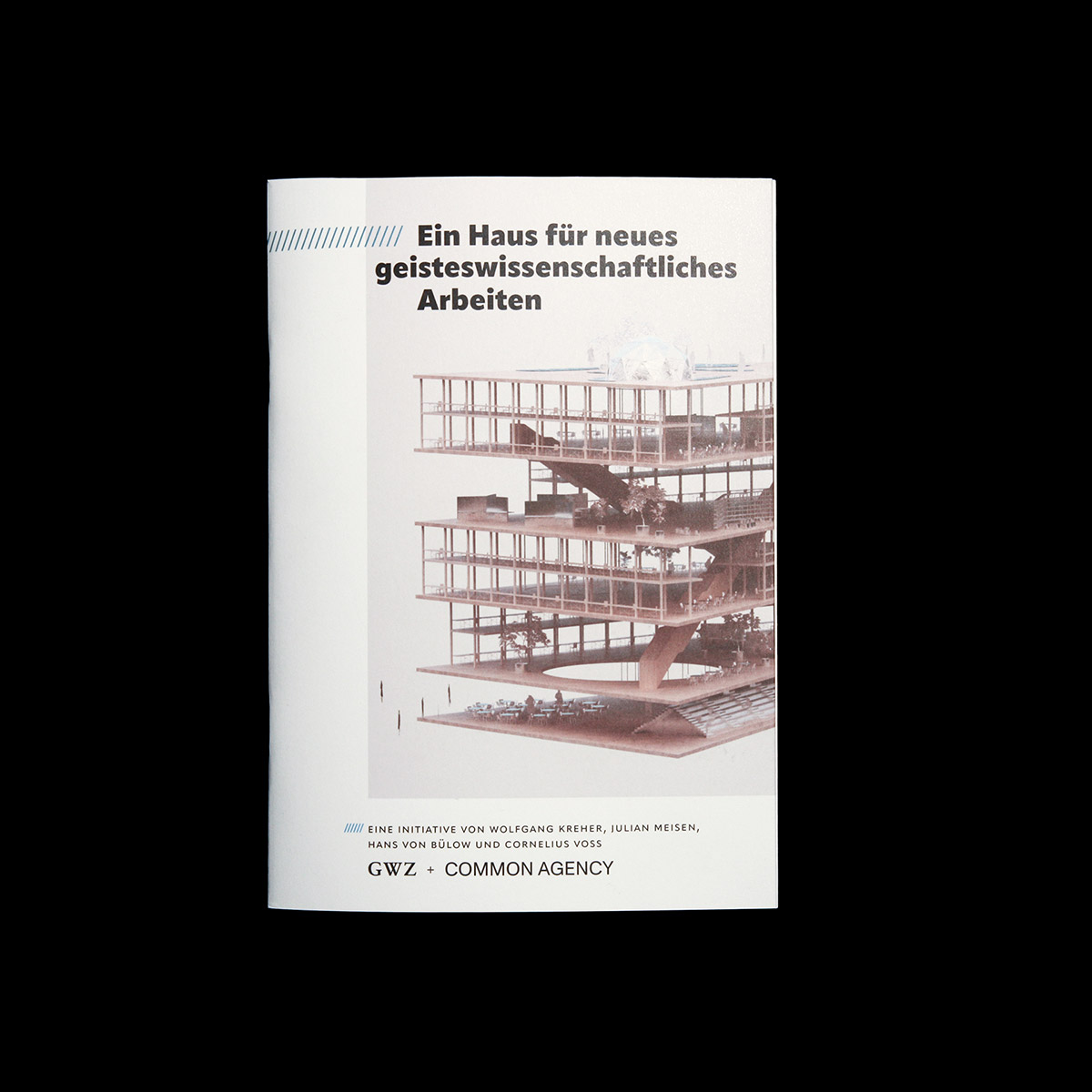

Haus für Neues Geisteswissenschaftliches Arbeiten

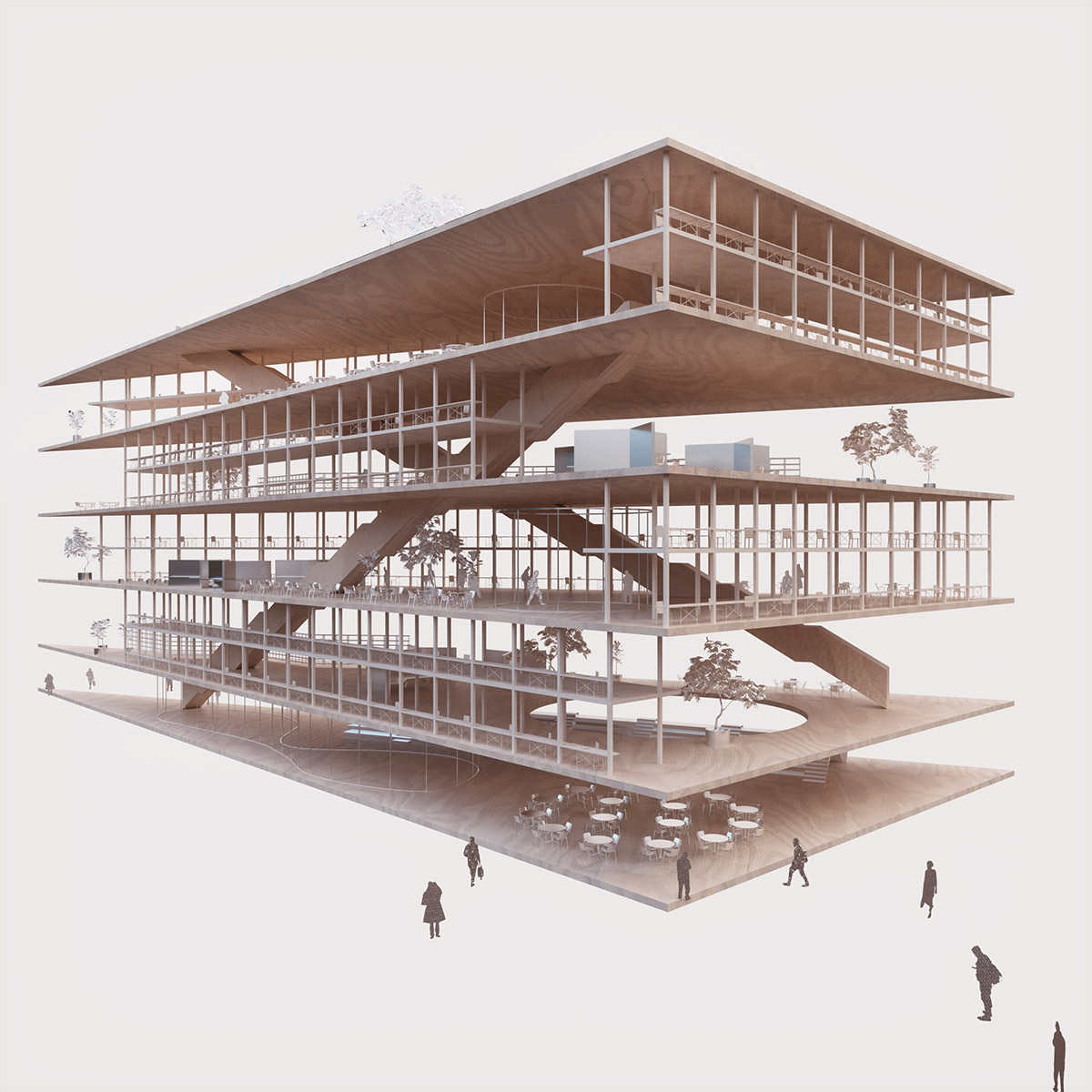

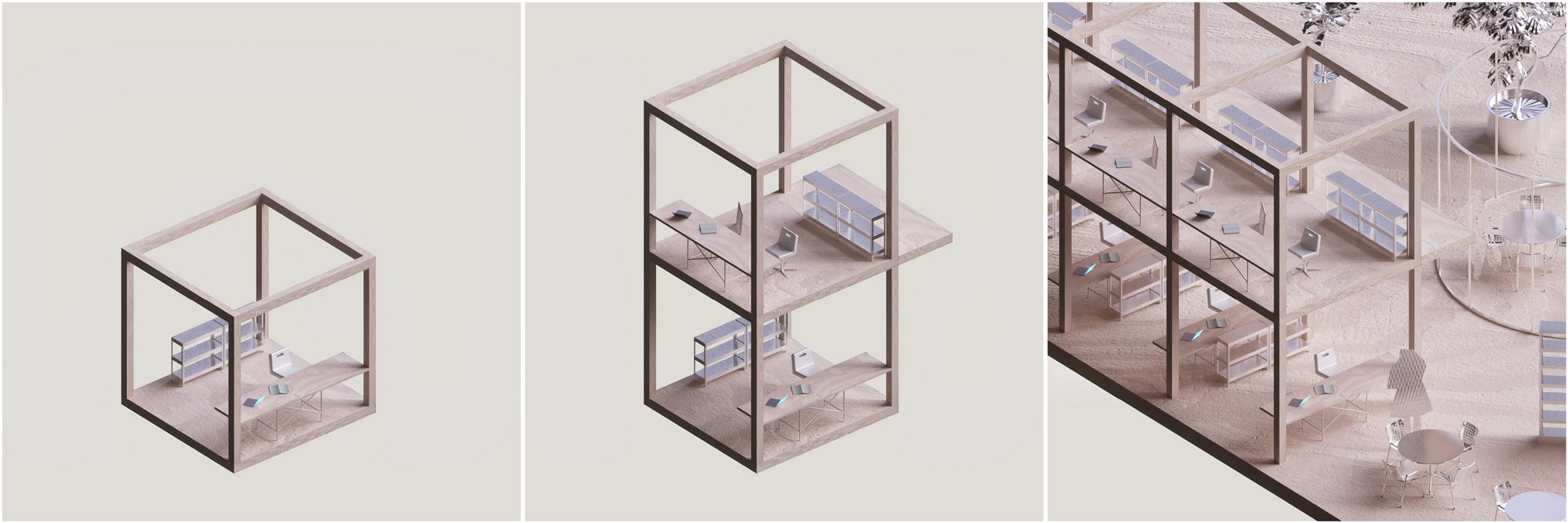

What effects can new work have on scientific research within the humanities? Together with Geisteswissenschaftliche Zentren Berlin e.V., an association of Berlin-based research institutes located in the field of humanities, we are initiating the development of a unique building type: A space where new work concepts are synthesised with the specific demands of scientific research in order to optimise and update the work environments of a number of Berlin based research institutions, which are currently suffering from rising rents and outdated work environments. Rather than providing just an architectural design, we conceived a holistic development concept, including spatial ideas, programmatic concepts, and organizational and financial structures.

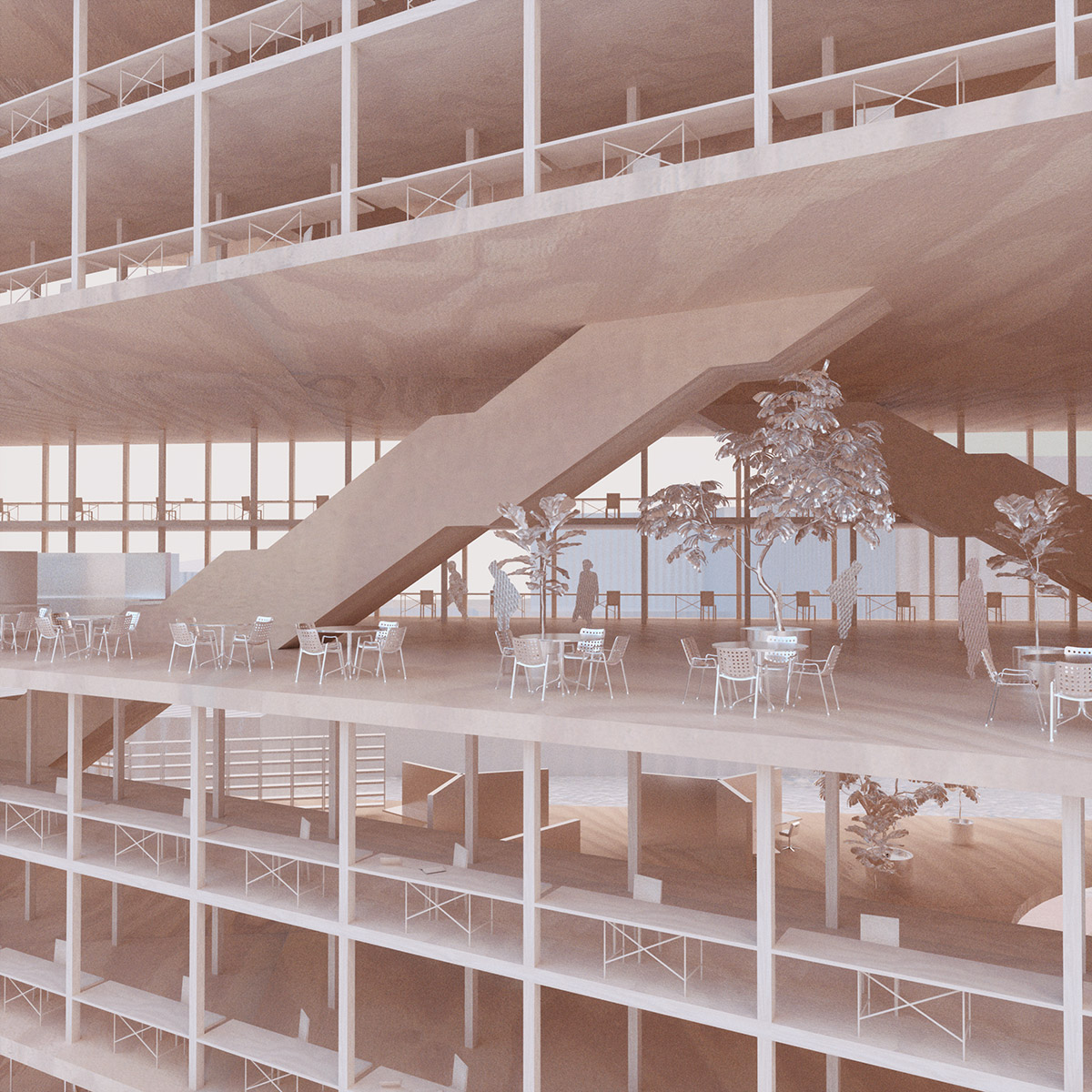

Since work in the humanities requires calm and concentration, our concept only partially adopts typical new work environments. Furthermore, the individual office – an unpopular typology within the new work discourse – is not fundamentally questioned but updated in reference to the concept of the studiolo, a medieval typology for room cells for research and contemplation. The proposed concept envisions a building subdivided into large double-height stories, in which two-level-structures of monastic room cells are juxtaposed with spacious and open workspaces.

Haus für neues geisteswissenschaftliches Arbeiten is still an idea without a location. To best illustrate its concept, the project is visualized on a vacant lot at the southern edge of Berlin’s Kulturforum in proximity to several culture and science institutions. The project is conceived within the legal framework of a foundation, which must be set up and controlled by the involved parties of the public sector. It is dependent on a long-term leasehold of a publicly owned property.

Website: commonagency.eu

Instagram: @commonagency_space

Photo Credits: © Common Agency, © Christoph Mack

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 07/2023