24/010

Daphne Karaiskaki

Architect

Paris / Zurich

«Architecture is for me the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.»

«Architecture is for me the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.»

«Architecture is for me the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.»

«Architecture is for me the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.»

«Architecture is for me the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

My name is Daphne Karaiskaki. I was born and raised in Athens, Greece, where I also studied architecture. Studying in my home town was a deliberate choice. I wanted to actively understand my own community’s architectural and urban culture. In 2012 I moved to Paris where I began practicing as an architect at Dietmar Feichtinger Architects and then at Renzo Piano Building Workshop. While questioning different career choices, I won my first competition and founded DKA (Daphne Karaiskaki Architecture).

It was a dream come true which allowed me to start paving my own path. That first project, a school, happened to be in Switzerland. My trajectory has been that of a nomad. From Athens I moved to Paris where I worked for an Austrian and then an Italian on projects in India and Russia. I started an office in Paris with a project in Switzerland. However, at heart, I am a person who likes to settle, as settling down is key to community building. And community is key to learning, developing and flourishing. At the moment, I am settling down in Zurich and about to start a new endeavor, together with one of the best architects and friends that came my way: Chris Chontos. Stay tuned.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time learning about architecture?

You are taking me a very long way back. So much so that memories start fading. As pretentious, exaggerated or romantic as it might seem, I actually found my way into architecture the very moment the concept entered my world. That was a child’s world of course, where someone must have said ‘well, an architect designs houses’ (I have never had, until now, the opportunity to design or build a house by the way). I am not trying to tell a story of an ‘inexplicable calling’ though.

The truth is factual and quite plain: as a child I sketched and painted well, so my environment encouraged me to do so. I had trouble deciding what to draw and always felt somewhat frustrated in front of a blank page (frustration I still have to be honest; briefs and constraints are saviors). When I grasped that designing could replace drawing, a whole new world came into existence. Why architecture and not any other field of design? The ‘poetic me’ will tell you that I was probably fascinated by the idea of ‘shaping what contains human activity’ or something of the sort; the ‘cynical me’ will tell you that it could also have been due to a lack of other references.

How do you remember your time as architectural employee/worker?

I must admit that from the outset of my career, I saw being employed as a necessary step towards creating a structure of my own. The actual experience, however, provided a multitude of valuable lessons that I look back on and cherish. I cherish the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’: working with talented, knowledgeable and generous professionals but also dealing with complicated dynamics and difficult situations. The first inspire, protect and educate. The latter forge, teach, and hopefully contribute to breaking patterns. Learning the hard way is unnecessary. This last phrase summarizes quite well my outlook as an employer.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your projects?

As explained above, I consider myself a nomad. At the moment, I am continuously on the move, mostly between Paris and Zurich. I also maintain ties with Athens and aspire to reinforce these connections. All three locations have a great impact on the way I practice architecture and have proven to be very complementary in the values they add. Paris is a huge metropole; one of Europe’s most important hubs, an eye to the world. Zurich offers an architectural community like no other. Athens is a city of enormous potential. I think that practicing from different places at the same time provides lucid context analysis, puts discourse to the test, lifts biases and amplifies opportunities.

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

On the Train – Working Space – © DKA archive

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

The essence of architecture for me is the creation of social, cultural, aesthetic, environmental and economic value through the manipulation of space.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

To be courageous enough to err and to fail. To be courageous enough to choose learning over pleasing.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

Conversation. In the studio, during a walk, over drinks.

Do you think AI is changing the field of architecture?

Trick question. A short answer is doomed to be simplistic and a long one fits neither my expertise nor the format of an interview. I’ll take on the challenge whatsoever. Technology has always propelled architecture’s mutation. Big technological leaps, together with urgent humanitarian crises can be detected as the origin of all architectural ‘revolutions’.

While global consensus identifies climate change as the most urgent contemporary crisis architecture must take into account , the use of AI and its benefits are still largely debated and skepticism still seems legitimate. Among the many fears (unintended collateral consequences, ethics, security and privacy) two are most commonly related to architecture: job displacement and a devaluation of professional expertise. Time and again, the first fear has been proven false. Displacement is evolution. Concern about professional expertise, though, is a legitimate preoccupation.

Insofar as architecture is the intellectual and creative pursuit of designing and constructing environments of human activity (ChatGPT), I am very optimistic. I invite whomever might be reading these lines to reflect on the definition of intelligence versus the definition of intellect. Intelligence amplifies intellect. Would it work the other way round?

Personally, I haven’t really been using AI as part of my practice process, but I am eager to, and very curious to observe the results. Collection and sorting of data and references would liberate so much time for analysis, contemplation and creative processes. I don’t consider that an inspiring mood board or an accurate technical assessment can steal my profession away from me, but rather give me back the time I always claim not to have.

Project

School in Jura

Switzerland

2023

How does one approach a context so distant from their own experience and culture when that very context is intended to be used as core material for conception and design? The answer I found was ‘common ground’: the identification of themes and concepts also highly present in my original culture. The image I had of rural Swiss architecture when I started the project is now stereotypical and bygone. It awoke however a nostalgic feeling about the architectural environment I grew up in: an environment based and developed almost entirely on masonry, not only as a way of building, but also as a way of thinking. Retrospectively, I’d say that I needed a homecoming before taking a step further and breaking the cast.

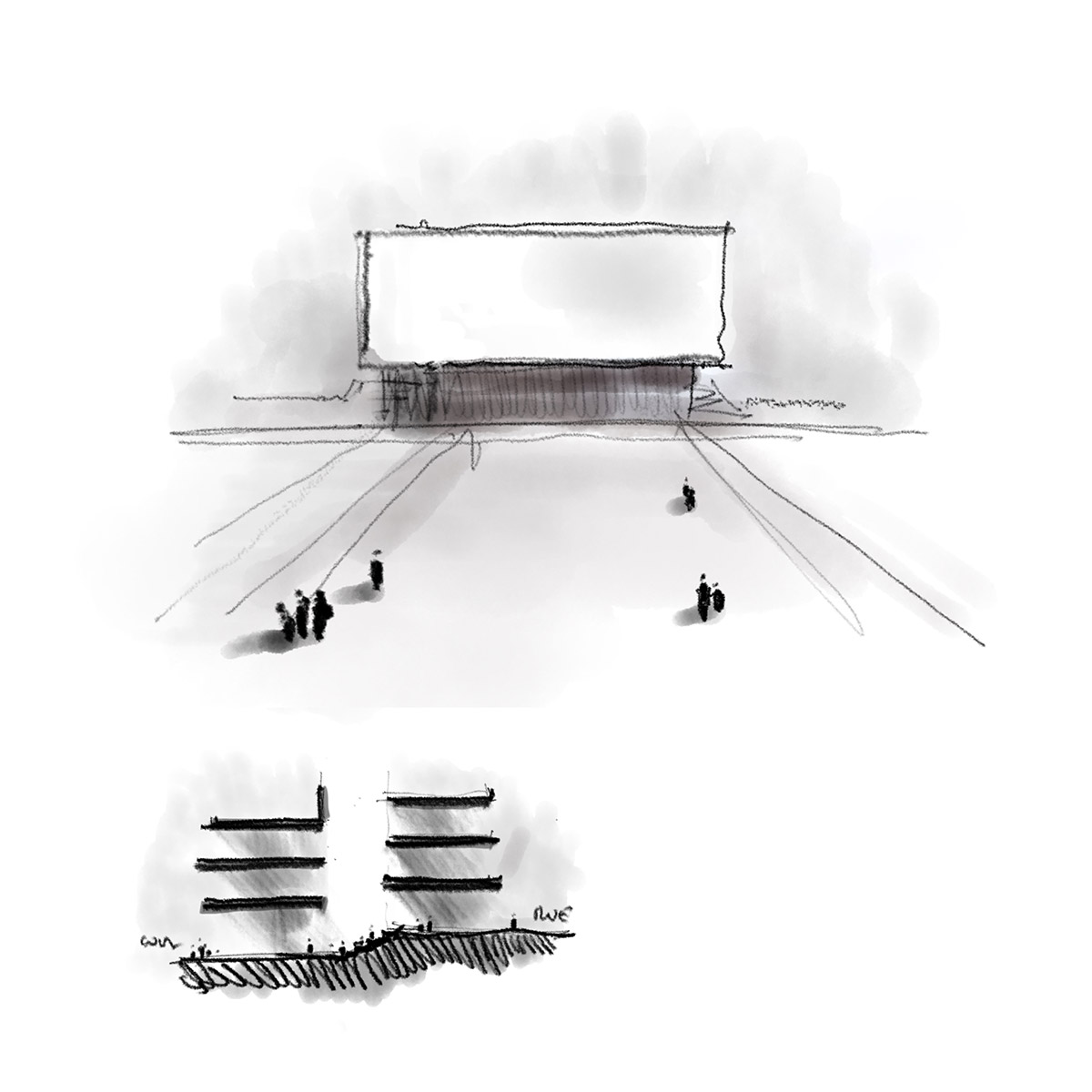

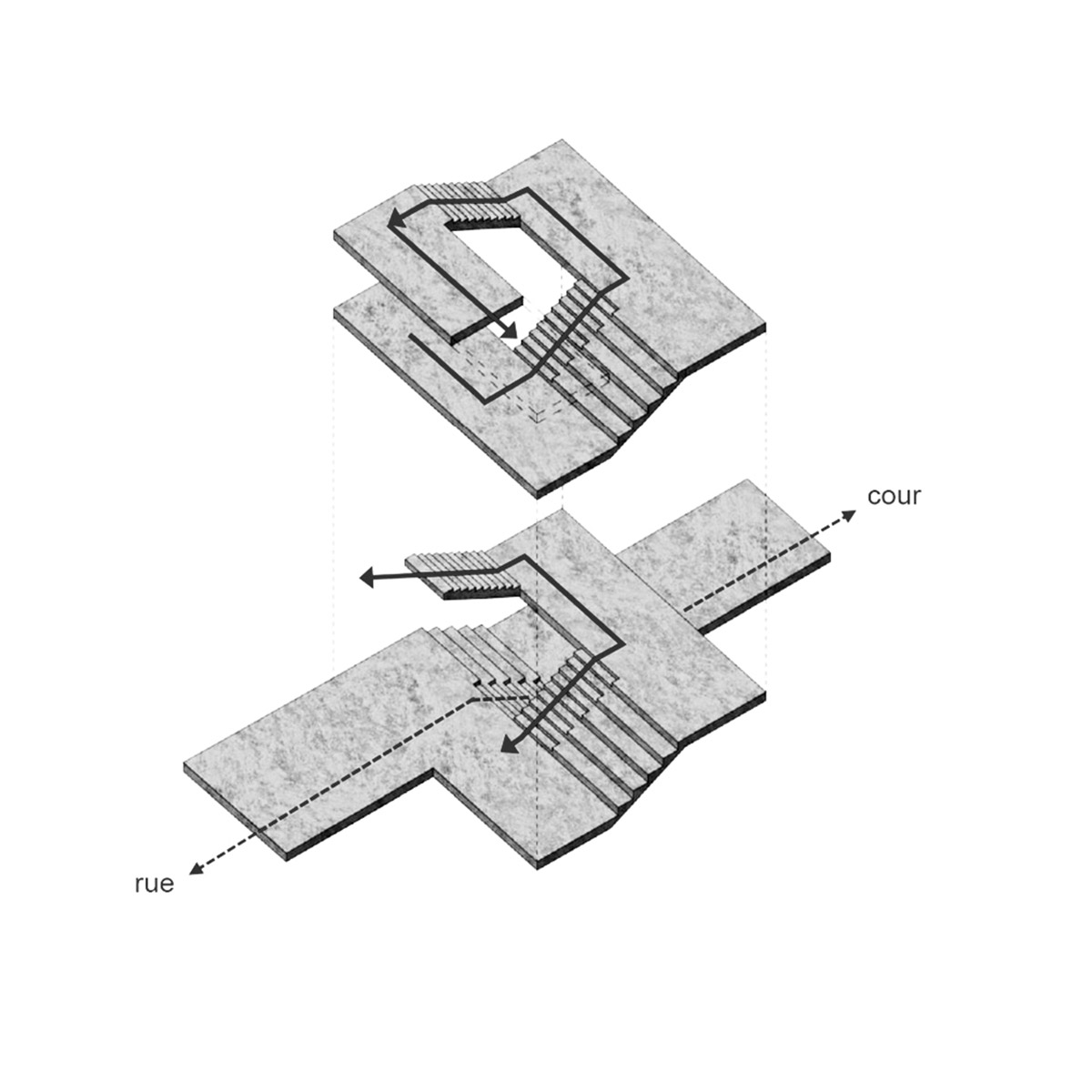

The project was born with a very simple, almost childish, gesture: the throw of a pair of dice on a board. One dice was a secondary school, the other a kindergarten. The board was a public area occupied by other school buildings (a primary school and a sports’ hall), lacking coherence and definition: it was neither a school campus, nor a public space embraced and used by the people. The first of the two dice, the secondary school, was completed in November 2023. The second is yet to come.

The design of the building was all about its relationship to the natural slope and the use of the school staircase as the main component generating space. The aspiration was to excavate as little as possible and save energy and means. The ground floor was split into two levels sitting on the natural terrain. The “split” ground floor gesture was repeated three times in section, thus creating an interior spiral where all floors became part of one single space.

A staircase is one of a school’s most important components. In most typologies (collective housing, office buildings and more) the elevator is the basic vertical circulation device. Not in schools. In this case, the staircase becomes the school and the school becomes the staircase: the split levels become landings of a huge ascending helix offering multiple possibilities of activity and interaction. The construction and materialization of the building is all about context and economy, insofar as economy goes back to its original meaning in the Greek language: administration of ‘the house,’ and consequently, administration of resources. A quarry and a forest were the resources available literally on the edges of the village. The concrete that was casted came from the neighboring grounds and the wooden beams used for the floors and roof were offered by the community.

Website: daphnekaraiskaki.com

Instagram: @dka_architecture

Photo Credits: Portrait/Working Space © DKA archive / School in Jura © Rasmus Norlander / Sketches – Schemes © DKA archive

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 09/2023