20/025

DF_DC

Architecture Practice

London / Lugano

«We are interested in architecture as an idea of order.»

«We are interested in architecture as an idea of order.»

«We are interested in architecture as an idea of order.»

«We are interested in architecture as an idea of order.»

«We are interested in architecture as an idea of order.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

We are Dario Franchini and Diego Calderon, and started DF_DC in 2016. Our practice is the consolidation of Dario’s previous practice in Lugano (since 2009) with Diego’s independent work in London after a long collaboration with Duggan Morris Architects. We work on strategies, urban places, and buildings.

Our smallest project is a staircase for a house (well, two), and the largest is an urban quarter with six housing blocks. At the moment we are working in Switzerland, UK, France, Mozambique, and Mexico, from our studios in Lugano and London. These projects include housing blocks, an art pavilion, a masterplan for an island in the Indian Ocean and private houses. We lead a small, young and international team, which gives a wide breadth to conversations and personal experience at the base of our work.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

We come from very different walks of life and met at the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio in the mid-2000s.

DF: I guess the interest in construction, on building as a process that attracted me towards architecture. Being from Ticino, the presence of Mario Botta as a kind of local hero (not constrained to the circles of architecture) was the reason to join the Accademia in Mendrisio. I planned to move to ETH Zurich after a couple of years, but it was the time when many of the professors I wanted to study with came to Mendrisio, so I decided to stay.

DC: I grew up in Mexico in a family of civil engineers, but realised early on that architecture was a more intriguing way to pursue. It was a time when not much was happening in terms of new visions for architecture back home (or at least in my perception) and decided to emigrate to Europe. We studied in a very small town and most people (students and professors) came from other places and that would end up being crucial in how we formed. Studying under Peter Zumthor was particularly revelatory, but the most important thing at the end was the ensemble of differing views and positions within the same school.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma projects?

DF: My diploma project was developed with Aurelio Galfetti, a territorial project with housing and public space in between Solothurn and Olten in Switzerland. It gave me a powerful lesson, that one can work at 1:25000 and 1:10 scales at the same time when dealing with the city. It also taught me how a defective city is the real context for architecture and ideas should not be dependent on a tabula rasa. It was also the most enjoying and exciting year at school, and the knowledge obtained from it is of such a general level that it can be applied to most situations.

DC: Mine was an infrastructural building for Alptransit in Ticino, in the atelier of Aires Mateus. I relish it as the last time of developing a project under “school” conditions, and although we haven’t talked about it consciously, lately we have been trying to return to an “elementarity”of space in our current projects and even more in competitions. Also, we look a lot at our time as students as a key part of our teaching, such as regarding the territory as the point of departure for every project. The academic vision is very different from the one in the UK, and we try to take the best of both.

What are your experiences founding DF_DC and working as self-employed architects in a collaborative structure?

We met in London for a pint (almost out of coincidence), and we talked about how interesting a London-Lugano practice could be. As the Swiss practice was already some years old, we experienced a sort of strong asymmetry (workload, scale) between the two offices. We have tried to make the most of it and to inform the ways of doing of each location with elements of the other.

Yucca House London / Photography © Rory Gardiner

Yucca House London / Photography © Rory Gardiner

These arrangements have forced us to develop a particular way of working. Although we meet every week for teaching, most of our crucial exchanges happen in distance, and these take the form of the media we rely on. It is a kind of structure that only a few years ago would have proved impossible. This is not limited to the logistics of our work but also permeates what we think and experience as architects. Competitions tend to be the most interesting occasion to illustrate the way we work (to ourselves) and help us clarify our stance on particular aspects of architecture. But mainly it is where we can put ideas to the test without the usual constraints, and the best of these always end up finding their way to our current projects.

Comano / Photography © Giorgio Marafioti

Comano / Photography © Giorgio Marafioti

How would you characterize and compare London and Lugano as locations for practicing architecture?

Needless to say, they are very different, and, in a way, that is why we didn’t choose one over the other. Lugano is stable and ordered as a scene, a sort of clear map for a territory. Construction and procurement are very well organized, and the proximity to Italy makes gives it a special cross-border condition. The process of Planning is also very distinct to the one in the UK and as a result, projects evolve in their own way depending on their location. We find this syncopation interesting and try to extract lessons for one context from the other.

The scene in London is more unstable and open, which makes it easier for a foreigner to set up and develop. Its raging flow of people and situations, as well as more obvious things like its scale and history, makes it quite an intense base to work from. We enjoy the spirit of collaboration and camaraderie, the network of people from work and academia with whom to share our personal experiences, views and frustrations.

It is in this double condition that we look for circumstances and cracks to produce work. At the same time, it is well known that Switzerland is one of the best places to win public work as a young, small practice, so it remains a promising location.

What does your working space look like?

Our studio in London is on the top floor of a Victorian building in Holborn. Despite not being very large, we have arranged it in three areas (drawing, making and meeting), full of models, fragments thereof and samples. It is one of the few buildings in the area not turned into co-working space, stairs are labyrinthine, and it feels like an atelier. There is another practice in the building (HASA architects), with whom we exchange thoughts, cross-crit our work, and drink a beer on Fridays.

In Lugano we are about to move to a new space in one of our soon-to-be-completed projects, so we had the chance to design and control the whole thing. It will be arranged over a long table and it looks directly over Lake Lugano. It also sits over the railway, so one can say it’s very archetypally Swiss.

Studio in Lugano

Studio in Lugano

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

We are interested in architecture as an idea of order. This is, how one idea can be used not as a solution itself, but as the vehicle with which to reach it. This idea conditions absolutely everything, and at some point, it can take over the process through consequentiality.

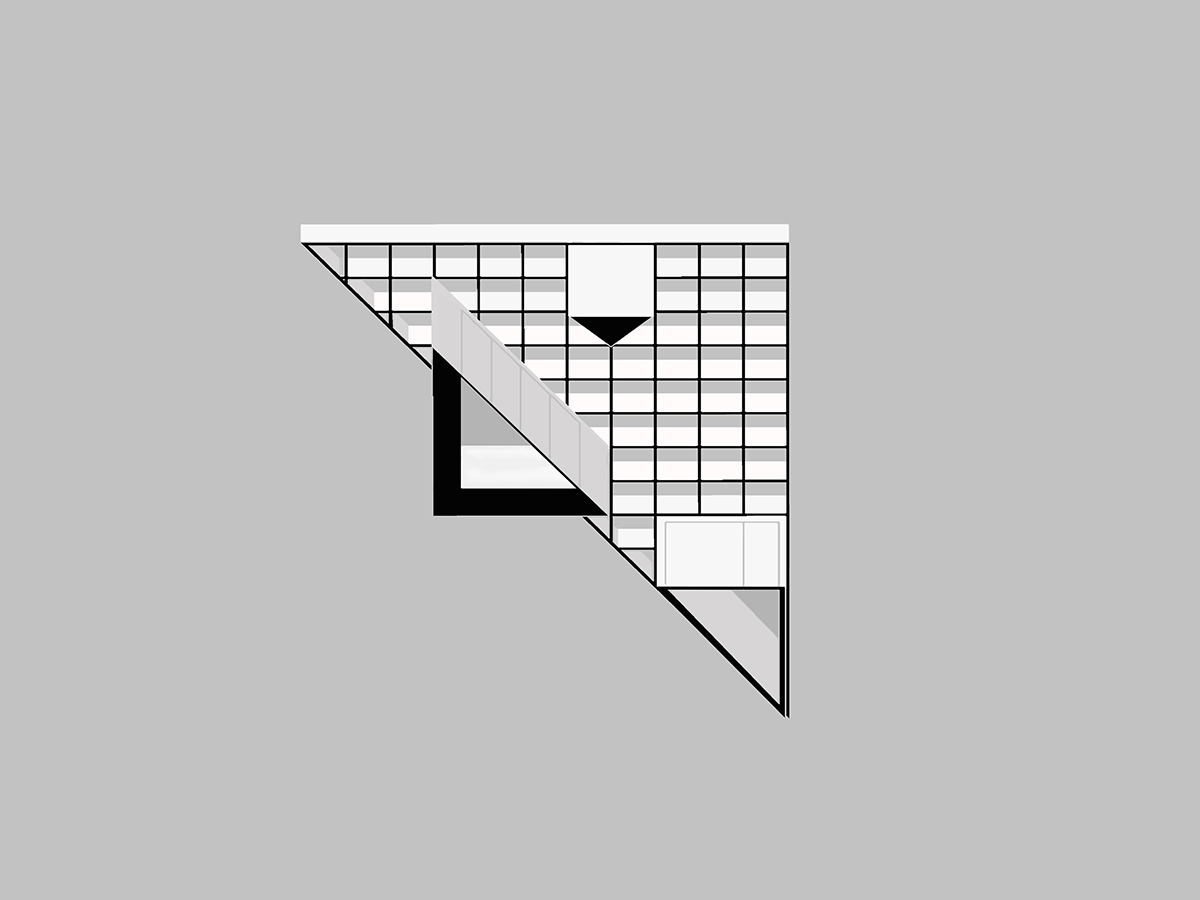

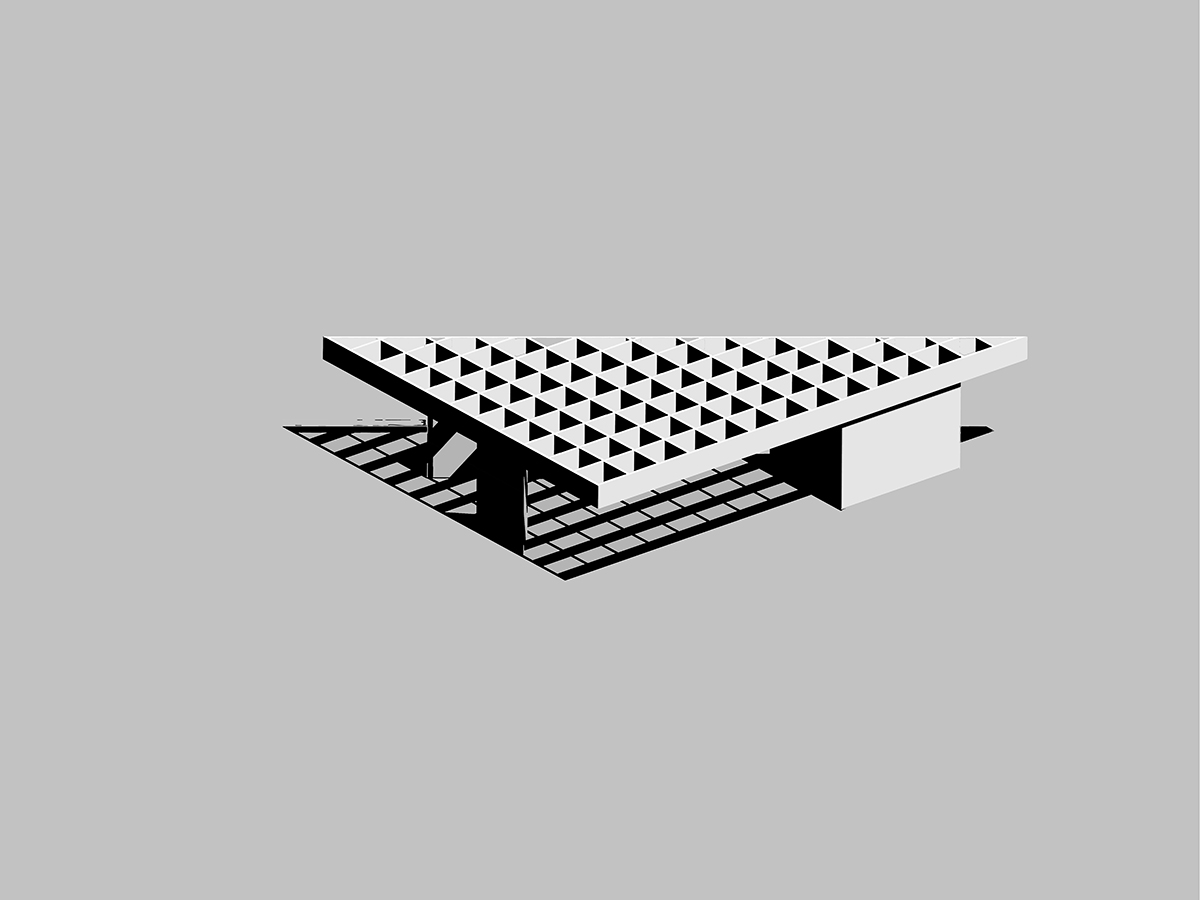

Vaud Cantonal Tribunal, Lausanne (Competition, with Morris+Company, 2019) Visualisation by Ver3d

Vaud Cantonal Tribunal, Lausanne (Competition, with Morris+Company, 2019) Visualisation by Ver3d

Which material fascinates you?

We have been experimenting with an old technique called “strollato”, traditionally used in Lombard villas in the XIX. It consists on splatting a mix of mortar and aggregate with a trowel. It gets later sandblasted and the mix and qualities of the components manifest in a much more heterogenous way than cast concrete. We researched and tested in the Concrete Villa, and we there is an enticing video of it being applied by an old builder, which we use in our lectures on tectonics to illustrate the place for forgotten techniques in new buildings, however anachronistic and out of place they might seem at first.

Name a:

Book: Land Mosaics – “The ecology of landscapes and regions”, by Richard TT Forman. The concepts on landscape it develops (e.g. patch-corridor-matrix) are directly translatable to architecture.

Person: We refer to Bruno Reichlin’s lectures at Mendrisio quite frequently, not only in their wonderful content, but also in their form. He used two slide projectors and DJ’d his way through a multitextual reading of a topic as a model for a lesson.

Building: The Public baths in Bellinzona, by Aurelio Galfetti. We draw from it as a continuous lesson, however indirect a reference it might be. It gives us courage when we hit standstill.

Film: A Walk Through H (Peter Greenaway, 1978), an obsessive celebration of surreal narrative and maps. This tireless exploration of an idea, regardless of how apparently disconnected from everything else, makes us wonder if architecture can be an invention.

How do you communicate / present Architecture?

From experience we’ve learned to work with strategies rather than designs when communicating a project. This is not actually limited to communication, but to thinking architecture as a whole. The advantage we see is that by presenting in parallel the idea and the way it will react to contingencies at every level while remaining “unchanged”, we amplify the sense of feasibility with the clients. It requires an inherent flexibility and also a vision of how a structure will transform over time.

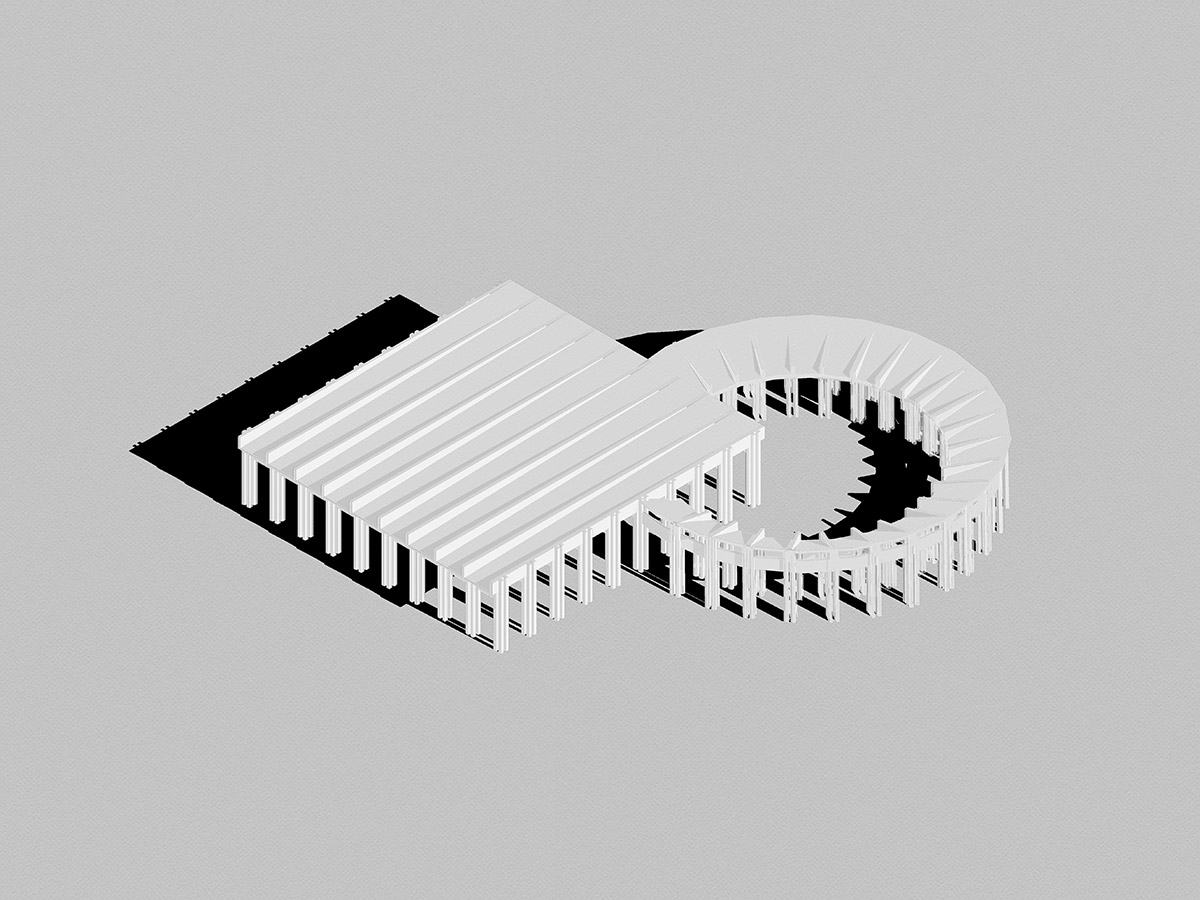

Lately we have been testing types of axonometric projection to present our projects between architects. It might seem almost naïve, but this gives them a sense of sequence in height -and thus of weight-, which is useful in understanding scheme and envelope as one.

What needs to change in the field of Architecture? How do you imagine the future?

We would like to see a more open, integral consideration on grey energy in buildings as opposed to the tickbox, label-based approach. This points at reducing the sometimes-excessive specificity and rigidity towards buildings that can change and recycle at a different pace over time, remaining useful and in transition. As architects we need to try to influence policy, regardless of where we are working. We would also like to see a shift away from the recent epidermic privilege of motif and pattern over substance.

What is your approach on teaching architecture? What do you want to pass on?

We always say we teach primarily because we want to learn, in a particular way that best happens with students. Teaching requires having a relatively clear view on what architecture is, where it exists, how it becomes (method, process) and how it is communicated. In a subconscious way, we think it must be a combination of how we were taught and a little of our experience in practice.

We are not canonical in any way and we bring honest questions to the table, for which we have no fix answers. This eagerness is what mutually feeds the relationship between teaching and practice. For example, this year we are working with our students with the idea of “elemental space”. Preparing the briefs and defining terms and purposes around it has had a liberating effect in our work at the office, be it in competitions or current projects. And most of it can be attributed to language: it is mainly through words that we can establish a productive bridge between school and office projects. At school we are compelled to have conversations and decisively addressing points that would otherwise be obviated at the office.

Before

Before

The volume is simplified by the new roof, which eliminates the intricacies and overhangs of the original, but fenestration remains unchanged. The upgrading of the envelope through external insulation crystallises the reinvention of the whole through the mix of grains of the render, applied as a series of geologic strata wrapping around the house, based on the datum of windows, parapets and other façade elements.

Photography: Simone Bossi

Website: www.df-dc.co.uk

Instagram: @dfdc_architects

Drawings: © DF_DC

Photography: © Rory Gardiner, © Simone Bossi, © Giorgio Marafioti

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 06/2020