21/029

Dina Dorothea Falbe

Architect + Researcher

Berlin

«Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible.»

«Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible.»

«Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible.»

«Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible.»

«Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible.»

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and the extended field of architecture?

I grew up looking at the world through the lens of architecture. My parents studied architecture in Hanover in the 1980s. I remember admiring hand drawn plans in their office and holidays spent as excursions to cities looking at architecture. In the 1990s we moved to former east Germany just before I started school. In school I often felt like an alien as a West German Kid. My parents engaged with city planning – saving old towns from decay was the major issue at the time. My fascination for the built environment as an expression of politics and society started with these experiences.

When I began studying architecture at Bauhaus University Weimar in 2009, there was a student initiative to start a magazine for architectural discourse called Horizonte – one issue every semester based on an open call for entries and interviews with guest lecturers. Each printed issue was designed by a new team of graphic design students. I joined the initiative in 2010 and I found what I was looking for: in depth discussions on current issues in the broad field of architecture. At the same time a group of students and teachers started campaigning for the university’s canteen building which was threatened by demolition. Research into the history of this unique GDR building was formed into a book financed by a crowdfunding campaign in 2013 – this book includes my first ever published text. Eventually the building got listed as a monument.

In 2015 I was still working on my master thesis in architecture at TU Delft when I applied for a journalist position at baunetz in Berlin – the most read online magazine on architecture in German language. I got the job. Then I got pregnant, finished my master thesis in Delft and moved to Berlin where I continued researching and writing about architecture.

What is the greatest challenge you experienced not being an architect, but working in the field anyways?

I guess the greatest challenge is to actually make a living from this kind of work. Journalism, writing and editing jobs are not paid very well, exhibition or book projects and university teaching don’t always pay off either. The challenge is to find a source of basic income and still take the time to do projects you’re passionate about – especially if you have a family.

A few years ago I started working part time at complan Kommunalberatung where I’ve been involved with a number of interesting projects like writing and editing publications and organizing events for municipal consortiums such as “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Städte mit historischen Stadtkernen des Landes Brandenburg” or designing a contribution to the exhibition urbainable/stadthaltig at Akademie der Künste Berlin. Being in charge of reconceptualizing the magazine “altstadtlust” has been an educational experience for me. I also get to do illustrations from time to time. It’s nice to have the opportunity to work in a team and learn from each other while still following your personal interests.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project? Does your diploma still have impact on your current work?

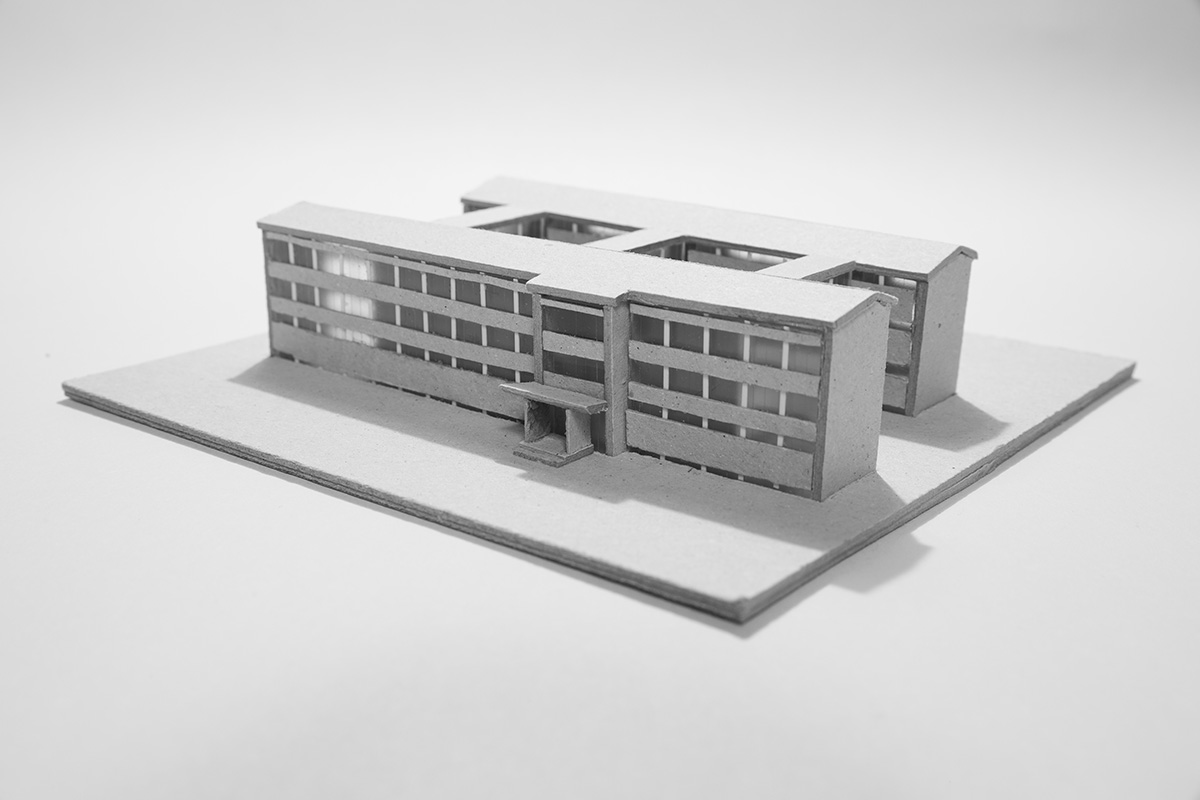

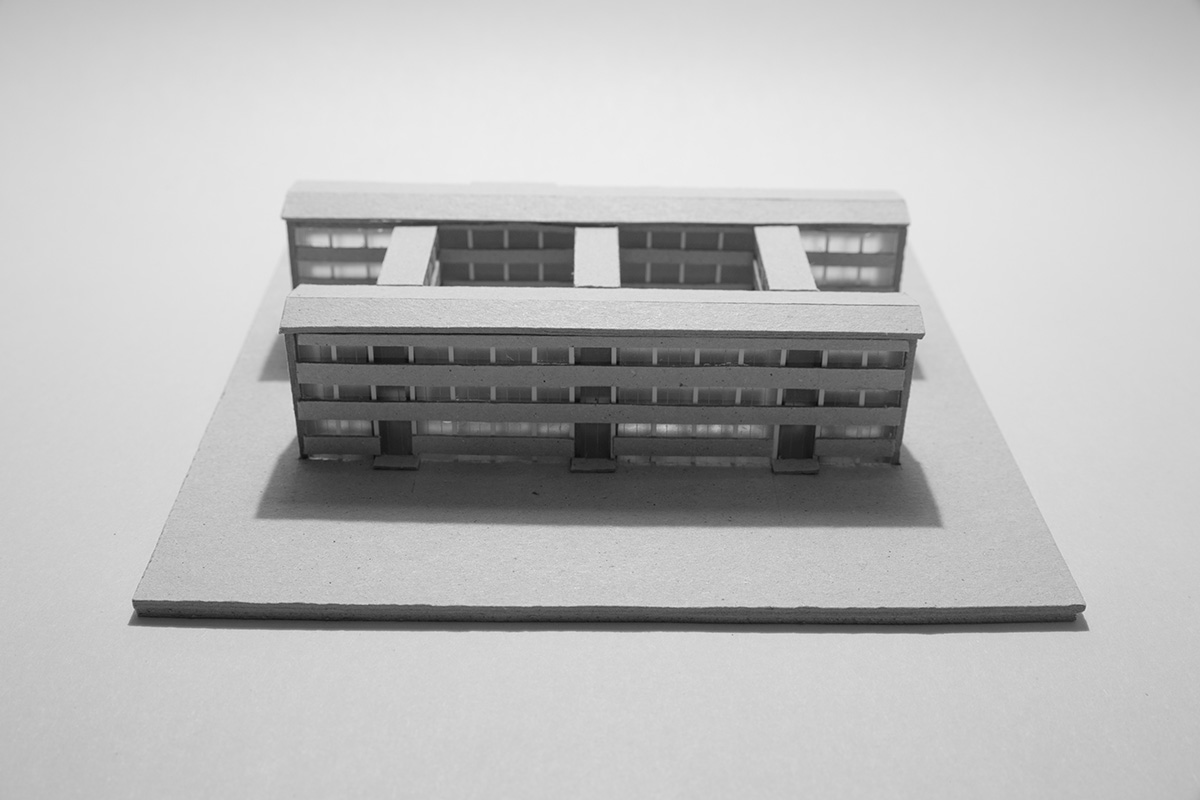

TU Delft, where I did my masters, offered a great learning environment – I would have enjoyed staying there a bit longer to do more courses and learn more about other fields of architecture. My teachers in Delft encouraged me to follow my interest and continue researching about 1960s and 1970s architecture. It was there that I started to develop the idea to the book on public buildings from this period called “Architekturen des Gebrauchs”, which I edited with my partner Christopher Falbe in 2017. My history teacher in Delft, Cor Wagenaar, asked me to write a PhD on school buildings in the GDR at the University of Groningen which I am still working on. I’ve been to four different schools and my favorite school building was a prefab type school designed in the 1960s. While we spent all day at school between two large window bands it felt like we were sitting outside – the ever-changing weather was also present. Unfortunately, the roof was leaking, and the building was demolished a few years ago. My primary school is interesting as well: a 1950s building in a village with a representative entrance situation. Since there is little research on these type schools so far, I want to find out more about the creation of these spaces. My research also helps me to understand some of the tension I experienced in a transforming society after the re-unification.

With the book project I got to know the community with a passion for GDR architecture so now there is also a network supporting my research. The online magazine moderneRegional also supported the project. Through them I was contacted by Kerstin Renz, guest professor for architectural history at Kassel university, who invited me to do a seminar on public buildings from the 1960s and 1970s around Kassel. I encouraged students to find a building they’re interested in and have a close look at it, so they can preserve what’s good, with or without monument protection status. I presented the results of the “Betonmonsterseminar” at the conference “75 Jahre Auf- und Weiterbauen in Kassel” for further discussion. So one thing led to the other.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

Growing up in the countryside I was always looking for cultural activities and Berlin seemed to be the place where it all happened. Later, journalism gave me an insight into architecture related venues and political issues in Berlin. I like that there is a diverse urban society with many people and initiatives demanding to have a say in city development and committed to finding suitable solutions on all sorts of issues. I believe that this commitment is super important to balance existing power relations and help the city to stay livable also for those who are often overlooked.

Berlin also has a rich heritage of historical architecture and built urban concepts. I’m especially interested in the post war period and Berlin has material for both East and West German case studies.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Working Space – Dina Dorothea Falbe

Name your favorite …

Books:

Start by reading “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” by Ursula K. Le Guin and “A Room of One’s Own” by Virginia Woolf to see why it matters what kind of stories we tell – be it with words or with architecture.

Then let me name a few recent publications about East Germany and post war modernism: Steffen Mau: Lütten Klein. Leben in der ostdeutschen Transformationsgesellschaft

Walter Nägeli, Niloufar Kirn Tajeri: Small Interventions. New ways of living in post-war modernism

Ben Kaden: Karten zur Ostmoderne

Martin Maleschka: Architekturführer Baubezogene Kunst DDR

Jens Casper, Luise Rellensmann: Das Garagenmanifest

Tobias Michnik, Leander Nowack: Übergangsräume. Bushaltestellen auf der Berliner Stadtautobahn

Falko Droßmann: Der City-Hof. An- und Einblicke

Novels:

Judith Schalansky: Der Hals der Giraffe

Birgit Vanderbeke: Das Muschelessen

Tijan Sila: Die Fahne der Wünsche

Daniel Kehlmann: Ich und Kaminski

Poems:

Rupi Kaur: home body

Hilde Domin: Nur eine Rose als Stütze

Buildings:

I love modern architecture, especially public buildings from the 1960s and 1970s when they offer spaces without any pressure of consumption. Kulturpalast Dresden (by architect Wolfgang Hänsch) for example has a lounge where students meet, pensioners read their papers and tourists admire the scenery. In Berlin I enjoy spending time at the Berlin State Library building by Hans Scharoun or at Kino International by Josef Kaiser und Heinz Aust.

How do you communicate architecture? Why did you decide to use this specific way of communicating/presenting architecture?

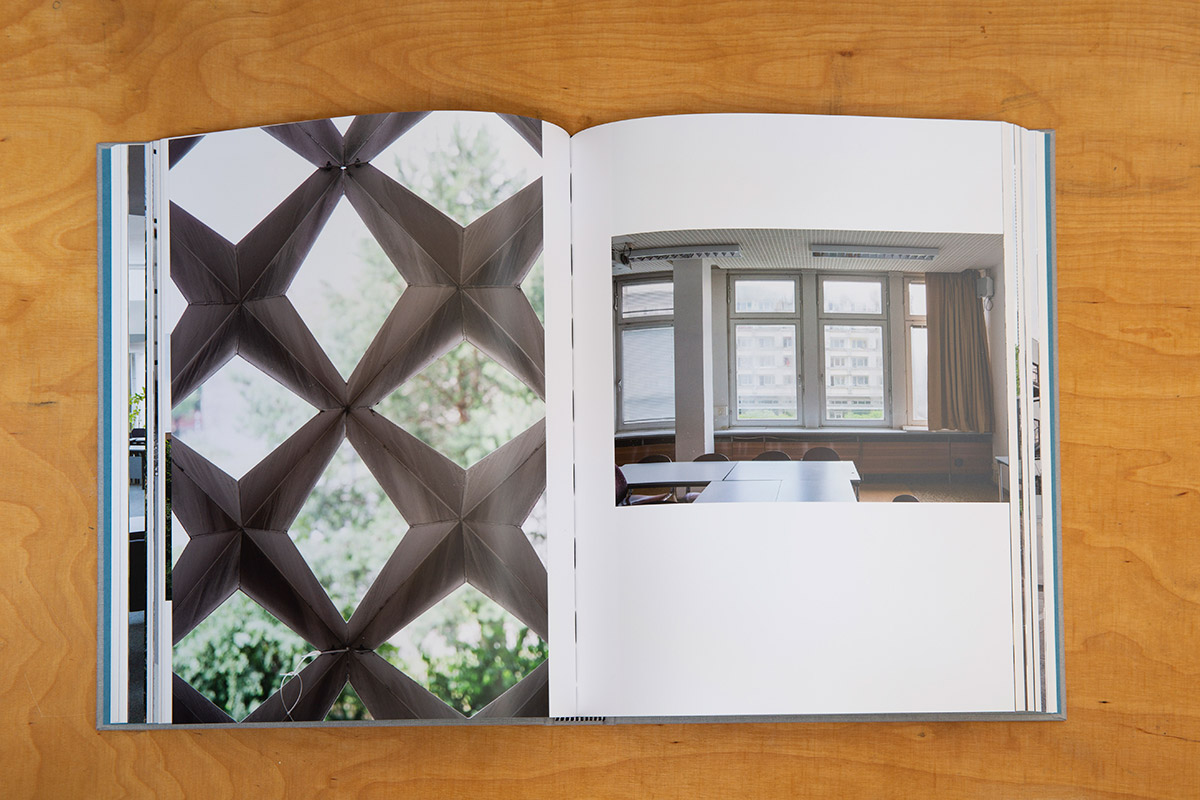

Although I have published a number of texts online I love print publications especially books. The biggest step towards indepence I consciously perceived in my life probable was being able to read a book by myself. To me a book is like a world on its own between two covers. I read a lot, not only books on architecture but also novels, poems, etc. I’m always excited about contributing to a book project. So with “Architekturen des Gebrauchs” the idea of editing a book ourselves was very tempting. When Christopher and I were studying, we were in a long-distance relationship, we would travel a lot for work and also to see our families. This is how we encountered the six case studies we explored for the book “Architekturen des Gebrauchs”.

We wanted to know why many of these buildings we saw so much potential in were still in use but not well-maintained. With our contributors we put together six stories about public buildings from the 1960s and 1970s: their planning process, their usage history and their changing perception within society. Christopher’s photographs, interviews with architects from the era, preservationist and texts by contributors seemed to be a nice collection to put into a book. Our publisher Michael Kraus from M BOOKS helped us to develop our idea further. Many people supported the book in a crowd funding, even Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz was among the supporters.

How do you understand the relation of theory/reflection and practice in architecture?

In my perception there is no truly convincing piece of architecture without a profound theoretical approach or at least some reflection on the history of the plot behind it. On the other hand, there needs to be a quality to the space that is only tangible physically, while you experience it – so a good intellectual approach is no guarantee for good architecture. Also places change over time and so does their perception within society – the interrelation is a process.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future? What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

Architects should question power relations and take responsibility for their impact on city development as much as possible. I believe that the rise of Initiatives committed to create spaces with a community value are a promising development. For example, if people from a neighborhood come together to revive an empty building and create much needed space for social gatherings, learning opportunities and support networks this can have a very positive impact on the city. It’s a form of self-empowerment and basic democratic culture – which is why I believe municipalities should support these initiatives much more than they do now. There are many promising examples throughout Germany such as Haus der Statistik in Berlin or a group of municipalities in NRW called “Stadtgesellschaft im Denkmal” which I had the opportunity to support. But there are also disappointing cases in which there are well-developed concepts and committed people but no official support.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

Look closely at what is already there and don’t forget the bigger picture – all scales are connected. Listen to people with different backgrounds respectfully and be open for discussions, they will help you grow. Take a stand and be open to new perspectives. Building regulations and assignments of clients can be limiting, so try to think outside the box and be creative: what do you think is best, and how can you make it possible? For inspiration I collected a few examples of architects who took an initiative to support the “right to the city” (Henri Lefebvre) in an issue of Baunetzwoche a few years ago. Surely there are more recent examples.

How do you perceive yourself as a female architect working in a male dominated field? What role plays gender in your work?

For a long time I liked to believe that gender didn’t matter in an intellectual discourse and I didn’t feel bound to any specifically female role. However, my perception changed when I was pregnant with my first child. My self-perception was challenged. I had always seen myself as an independent individual who could basically pick any path of a career. Suddenly physical constraints wouldn’t allow me to travel and work as much as I used to. So I realized that it is a basic human condition to depend on other people throughout your life, how important care work actually is and how little it is valued in our society. Since than I found myself increasingly interested in the perspective of women which often adds a new dimension to existing narratives (especially in historical research). I found that drawing comic zines helps me to reflect on my personal experiences around parenting, gender stereotypes and other feminist issues.

A few months ago, I came across a quote by feminist artist Ariel Gore: “[Jack] Kerouac … slaps us with the great fear we all share. He embodies the archetype of the selfish, self-destructive male artist, and he announces that unless we, too, are willing to be irresponsible to our relationships, we’ll never quite measure up. … Can we be present in our relationships and still do the work we feel called to do? … Women have always done both.”

Now with two children my partner and I still try to distribute care work and paid work in a way to allow both of us to follow our calling – sometimes we even manage to work together on the same project like very recently on “Education Shock” at HKW Berlin .

Project 1

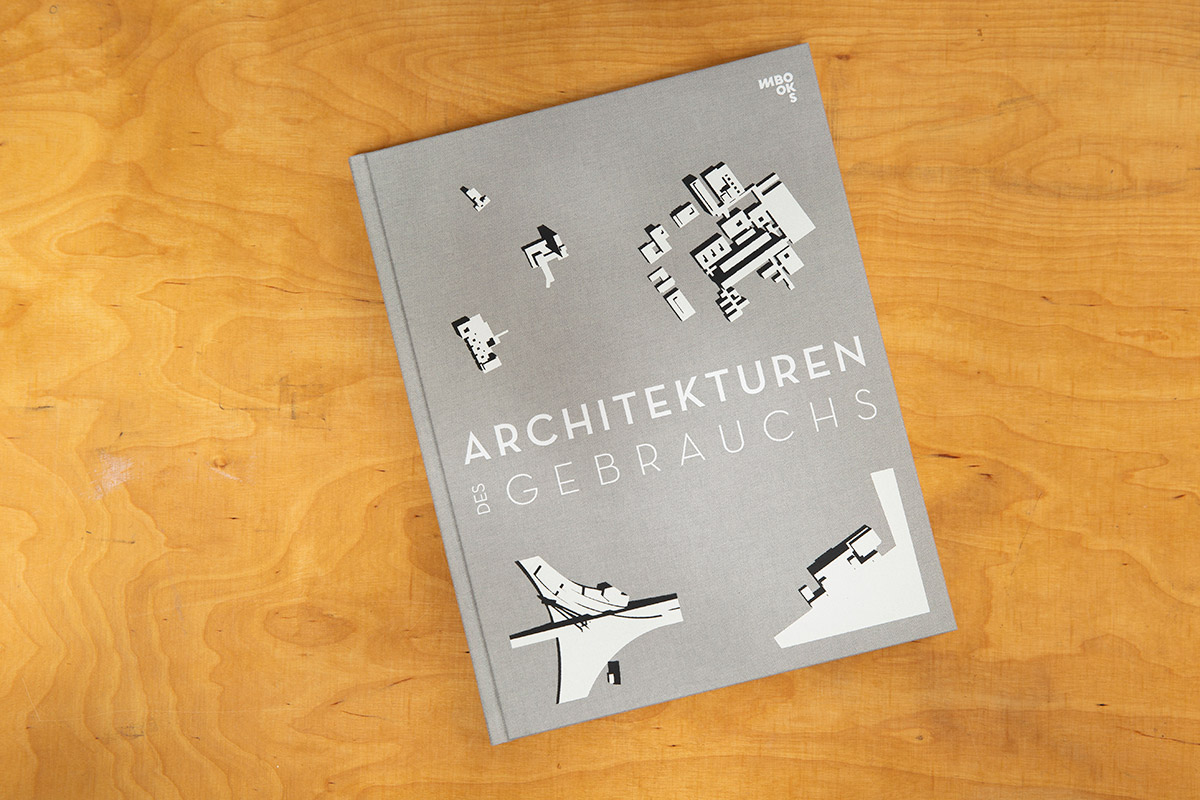

Architekturen des Gebrauchs – Architectures of Use

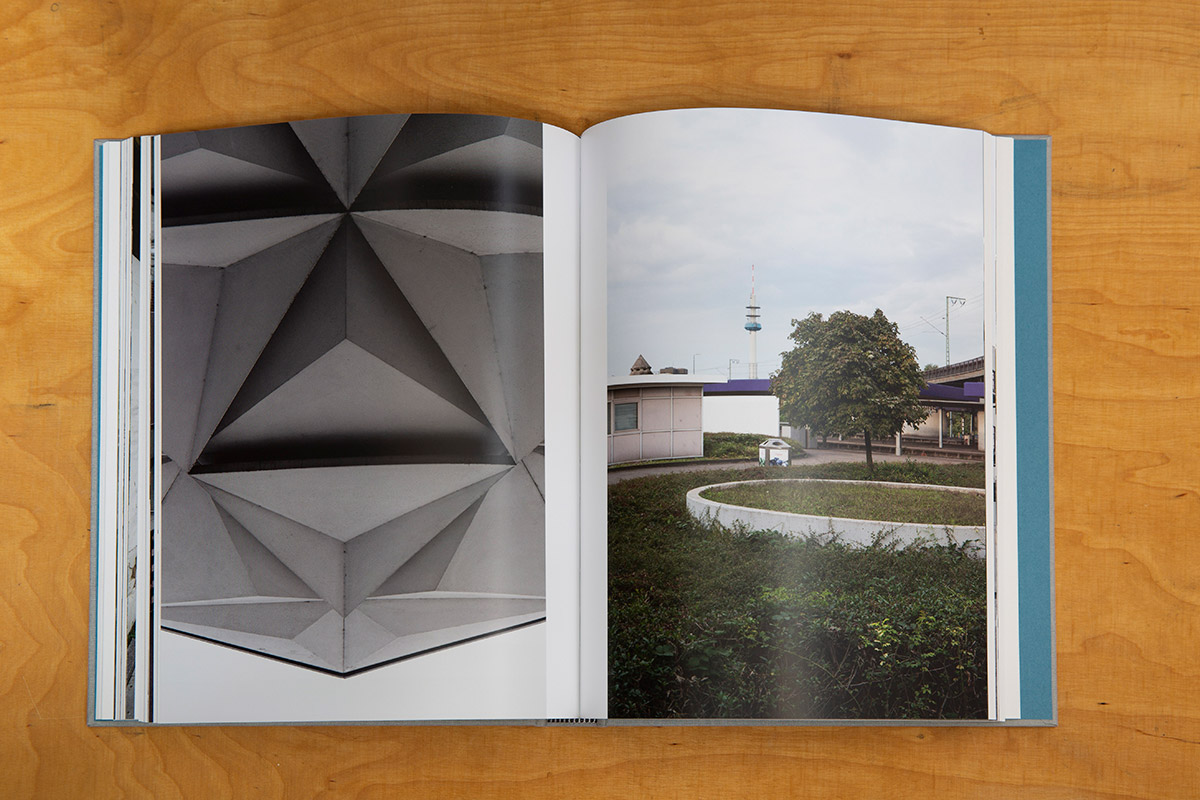

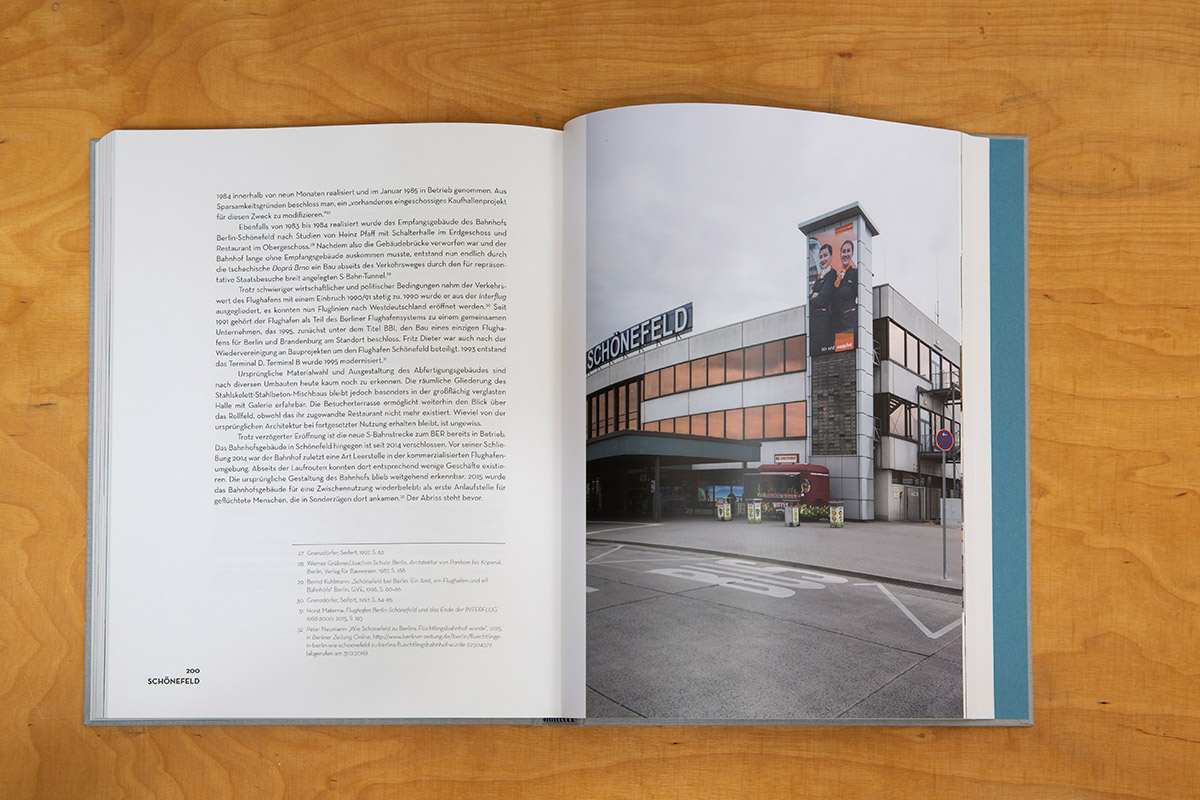

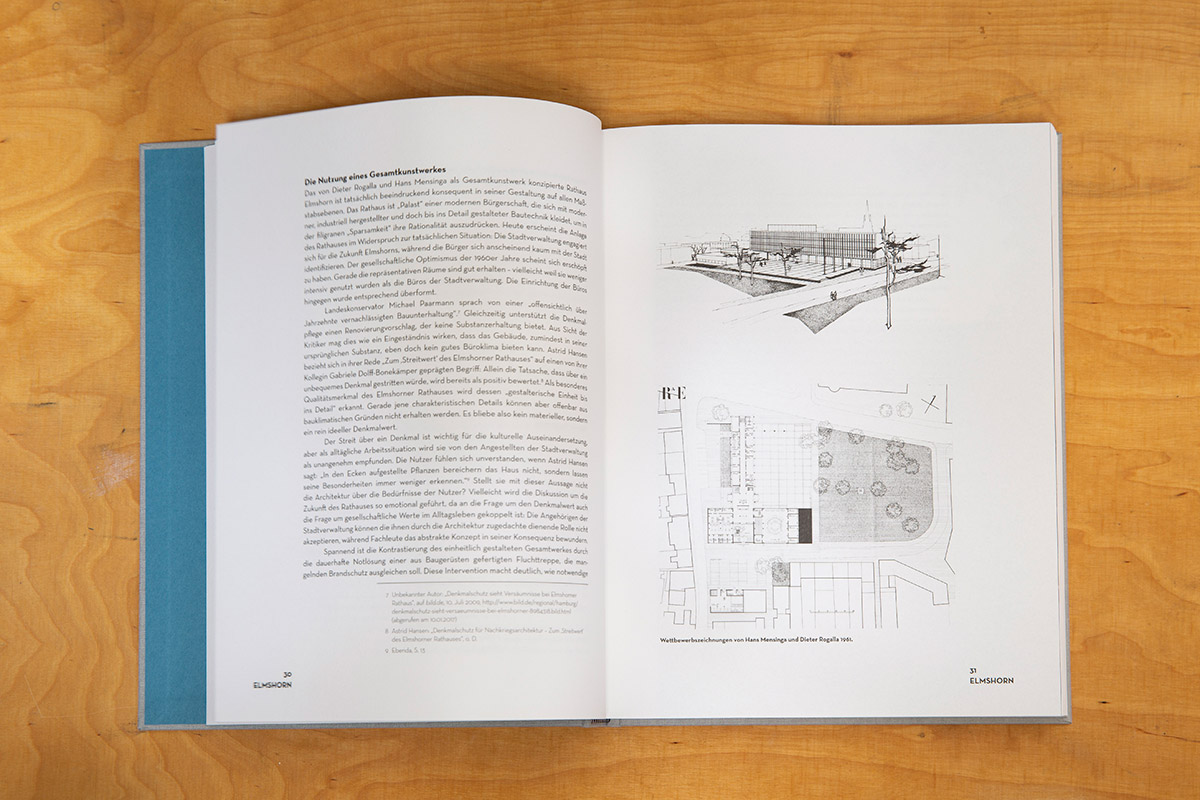

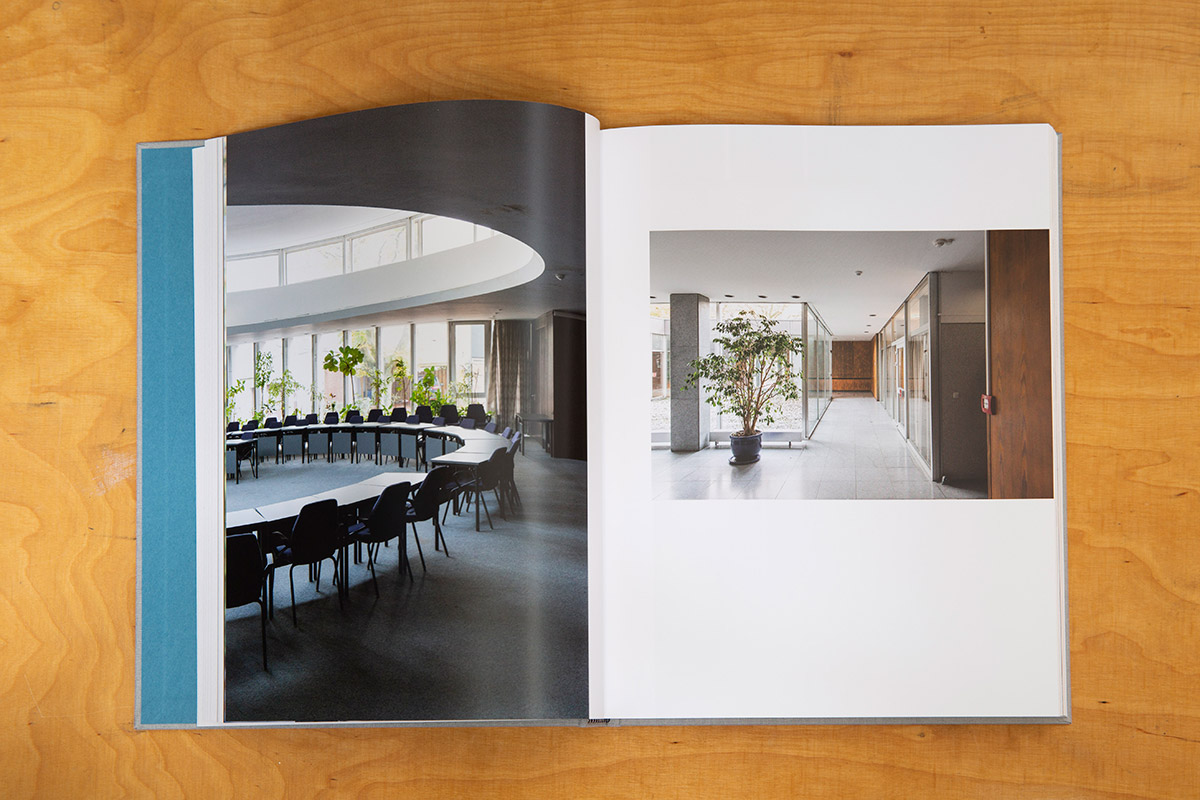

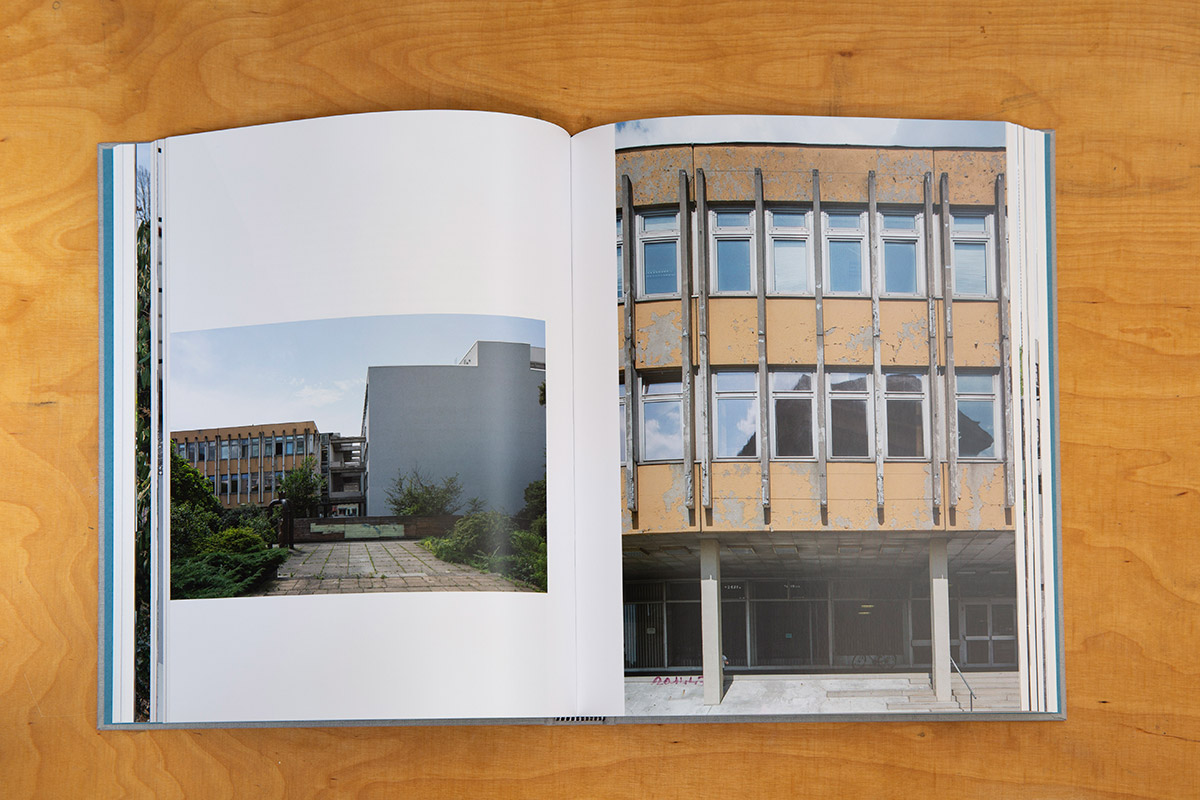

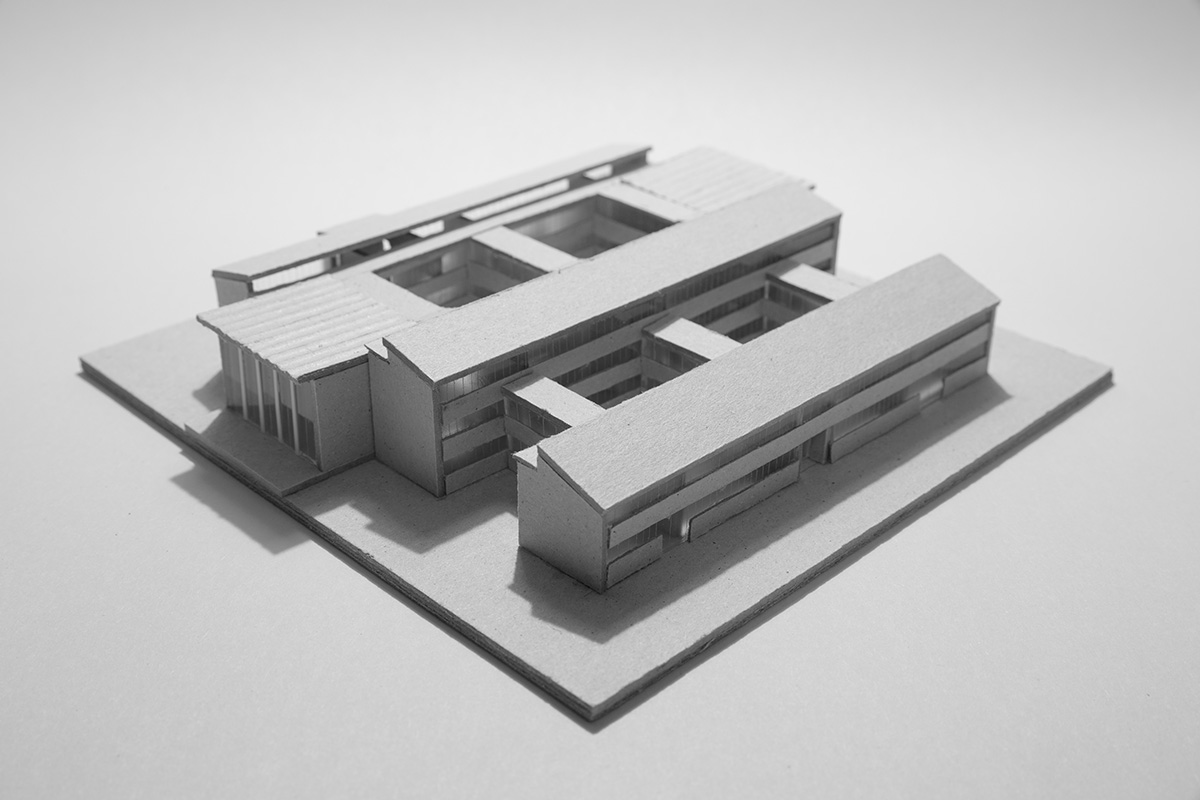

Architekturen des Gebrauchs – In the 1960s and 1970s, a large number of public and infrastructural buildings were constructed in both parts of Germany as a result of state involvement.The shape of these architectures is determined by the cultural Zeitgeist – a complex interplay of social processes, political objectives and practical organization. Progress optimism and social reconstruction efforts characterize the design of these buildings. In strong contrast to the former aspirations of the architects is today’s criticism of structural-climatic problems and aesthetic aspects of this architectural epoch and its buildings. The contributions in the book show, however, that between politics and aesthetics, the architecture of this period demonstrates qualities precisely in today’s use.

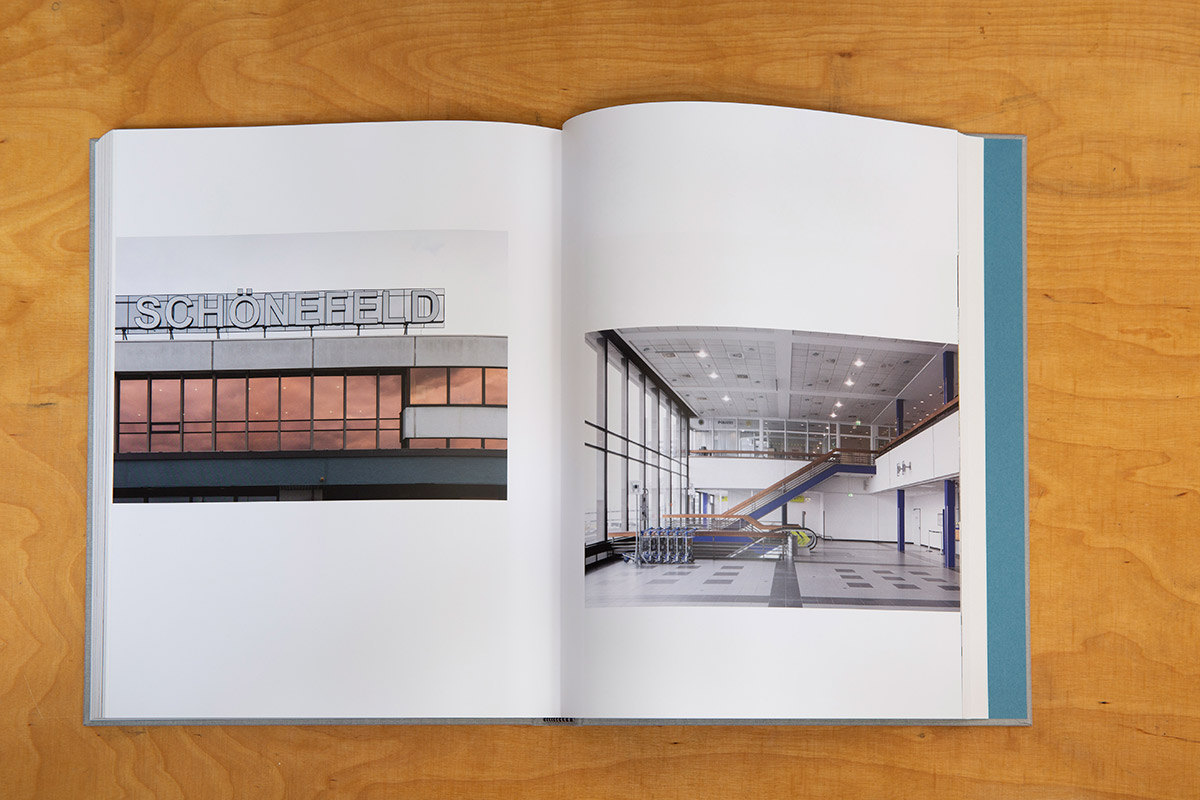

Architekturen des Gebrauchs(architectures of use) brings together six examples of buildings from East and West: Elmshorn City Hall, the Party School in Erfurt, Potsdam University of Applied Sciences, Hanover Medical School, Ludwigshafen Central Station, and Schönefeld Airport are presented in texts, photographs, and interviews. Between the architects’ design ideas and the users’ perceptions, the book discusses the social significance of the transformation processes of these architectures and thus encourages a reassessment of the modernity of both German states.

Editors: Dina Dorothea & Christopher Falbe

236 pages

20,5 × 26 cm

Editorial Design: Lauthals

German

M BOOKS, Weimar

2017

Architekturen des Gebrauchs

Project 2

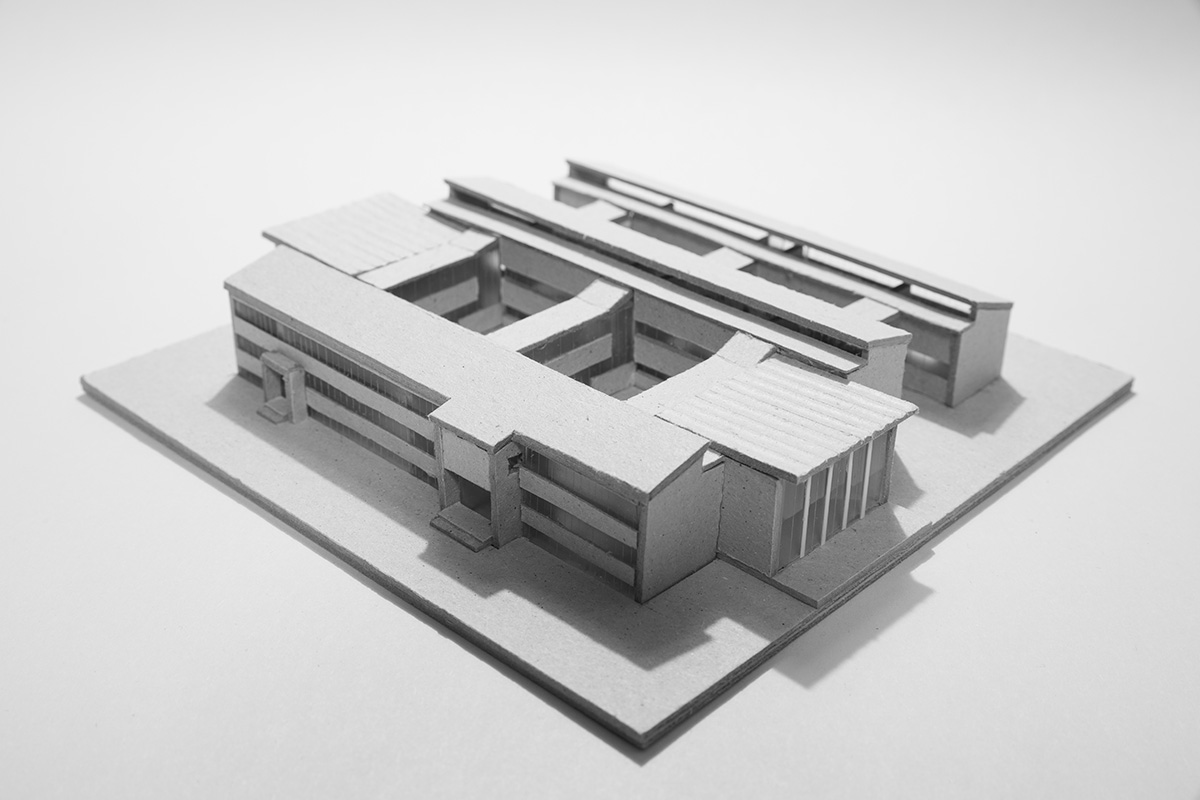

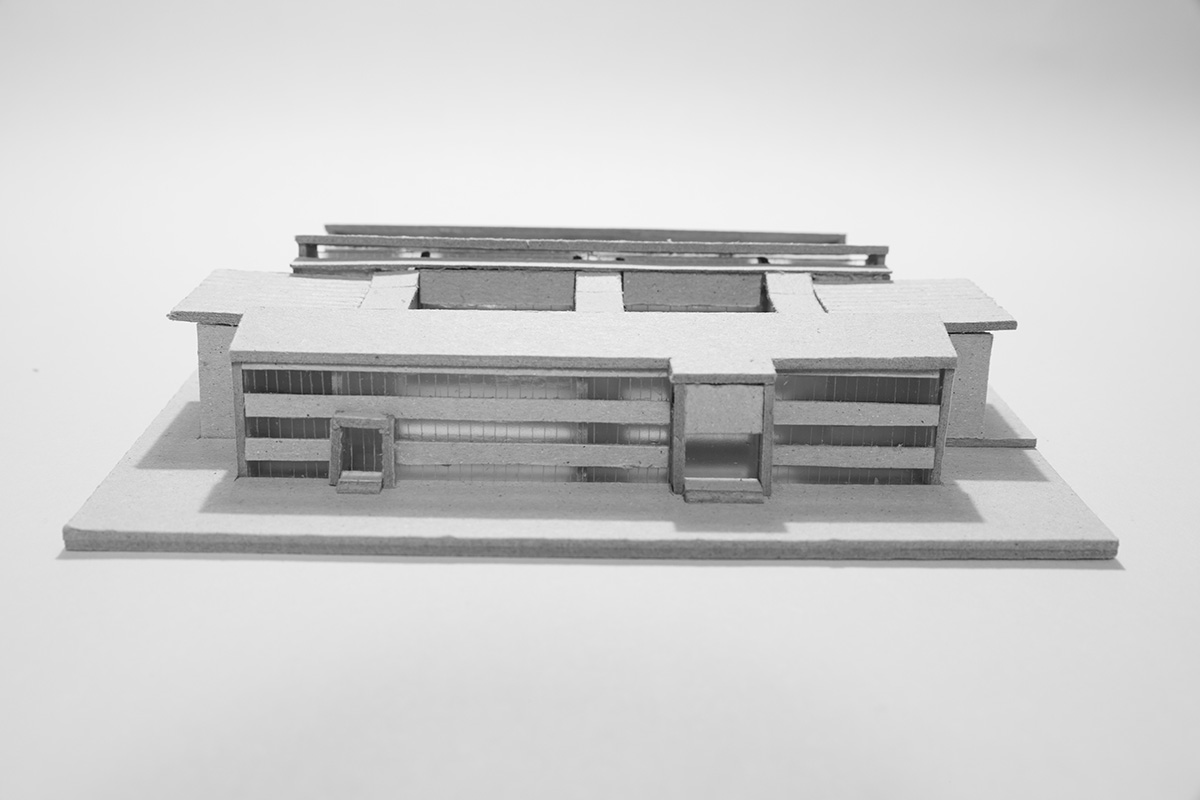

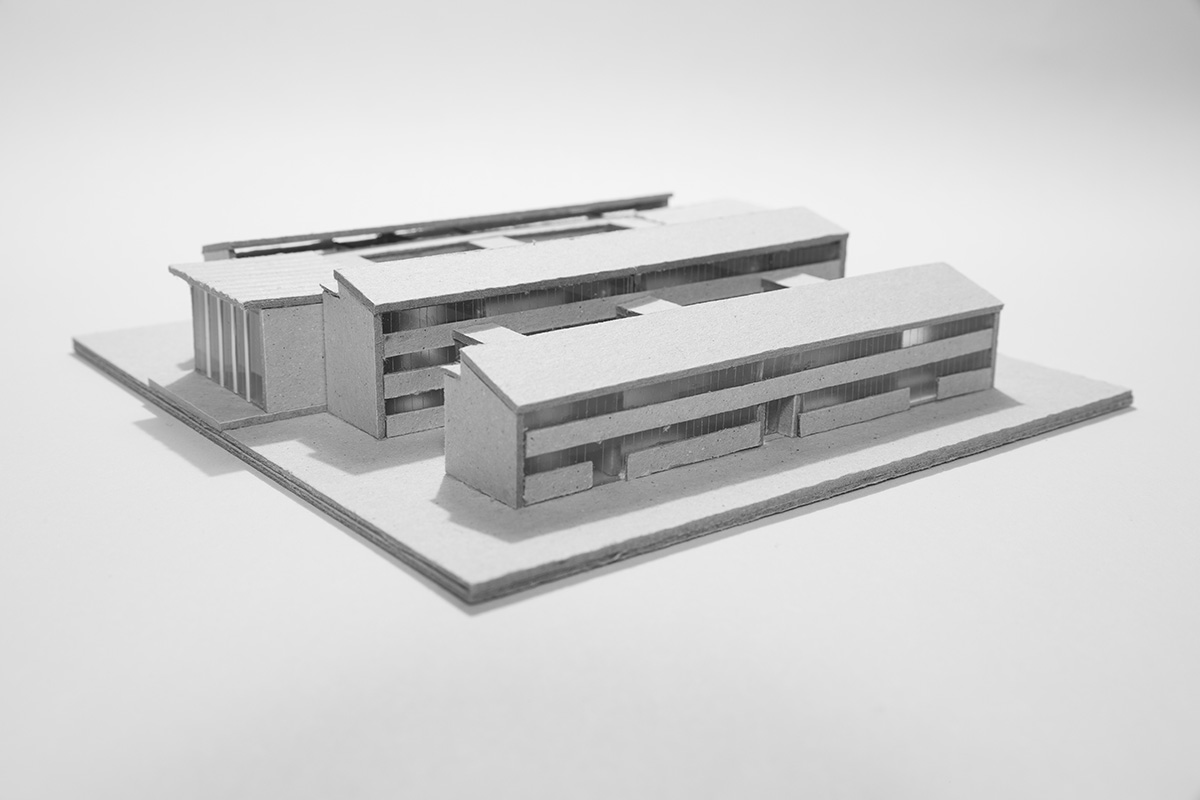

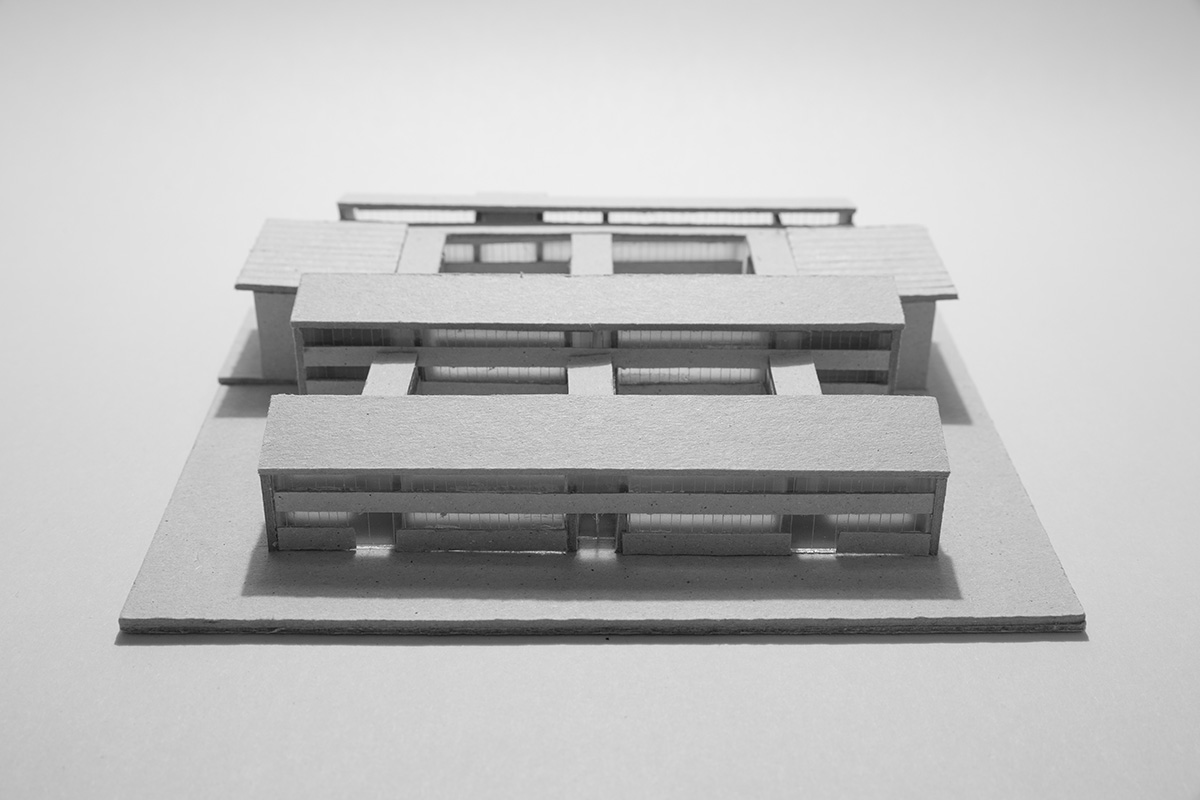

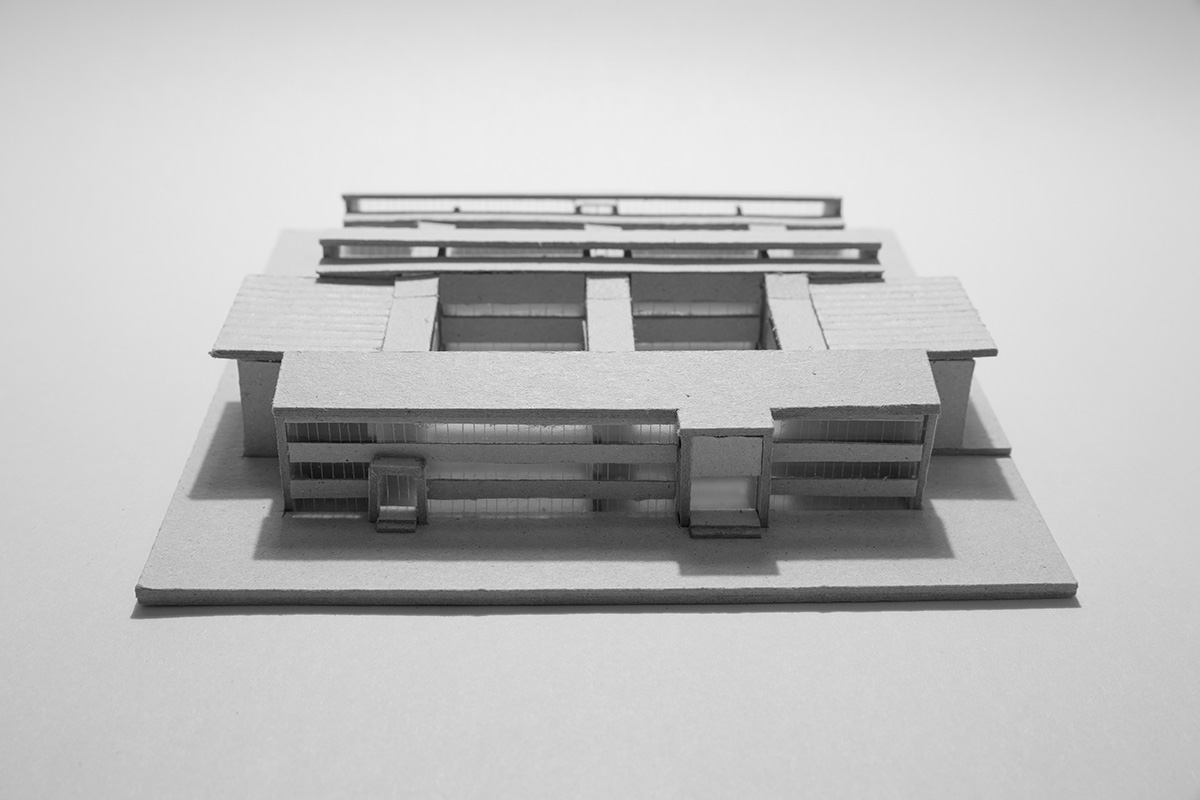

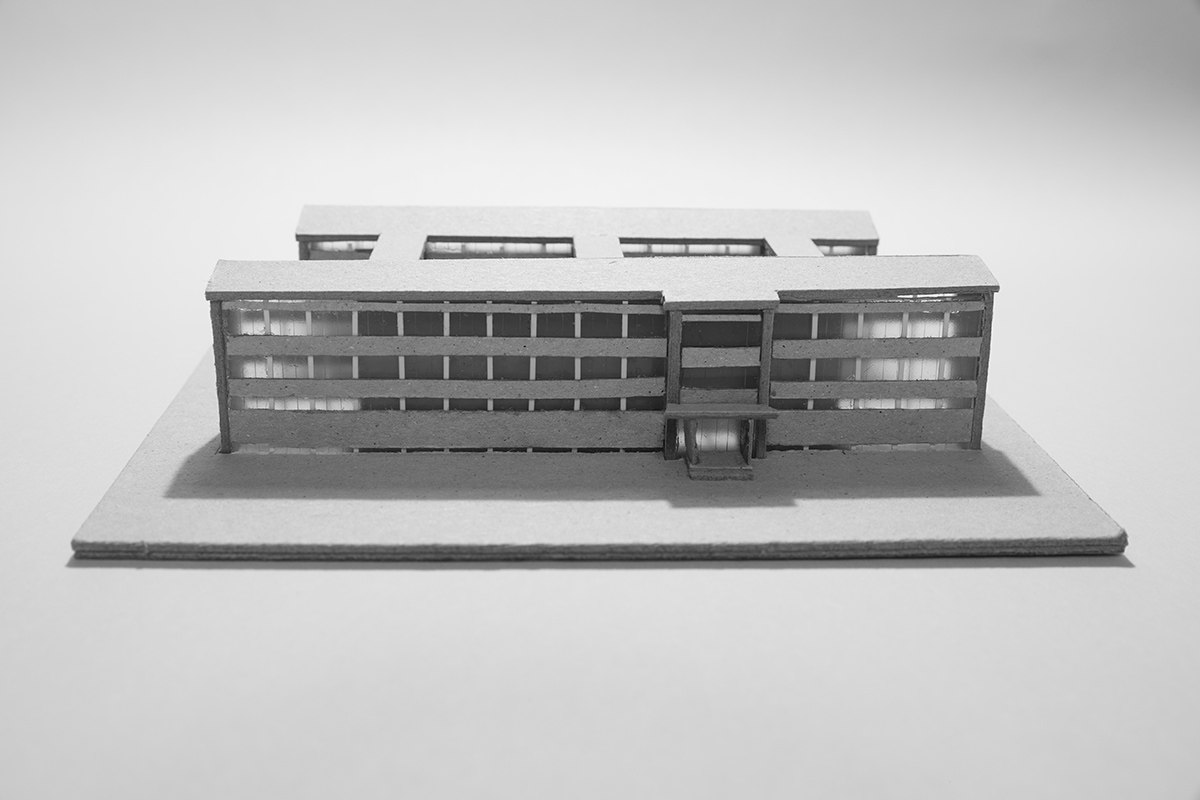

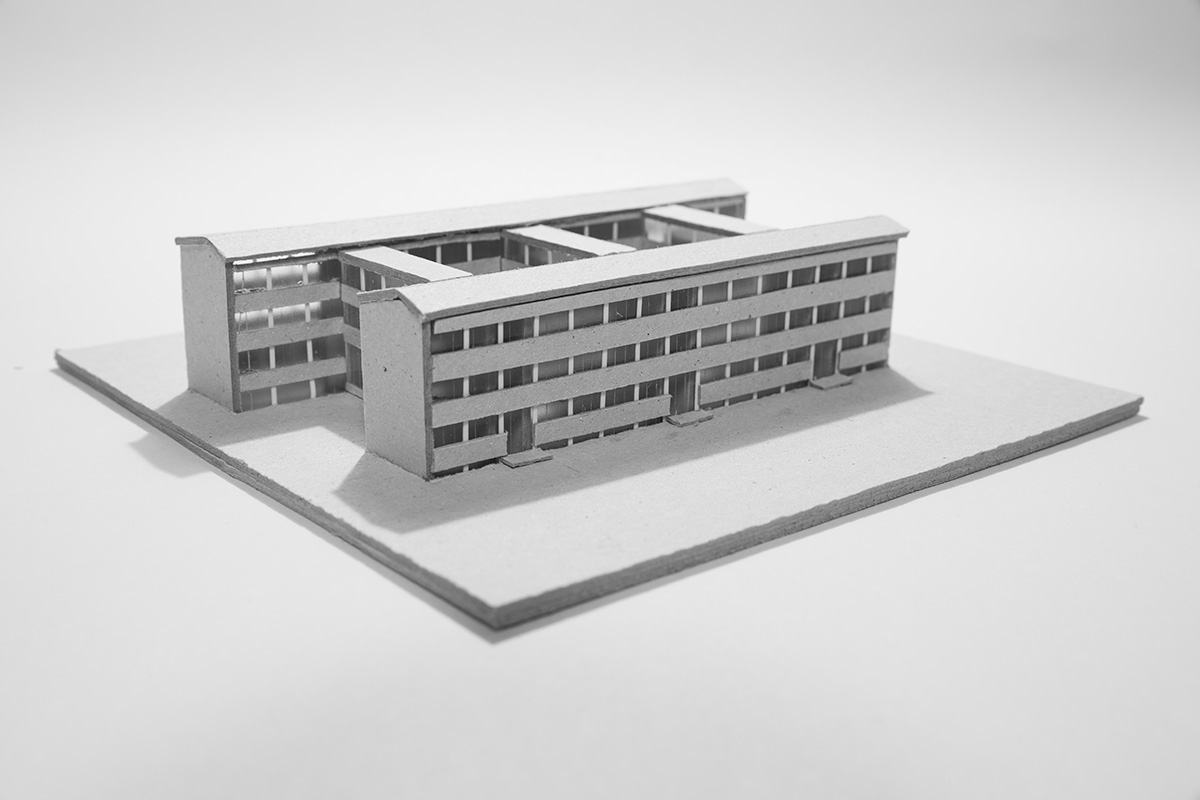

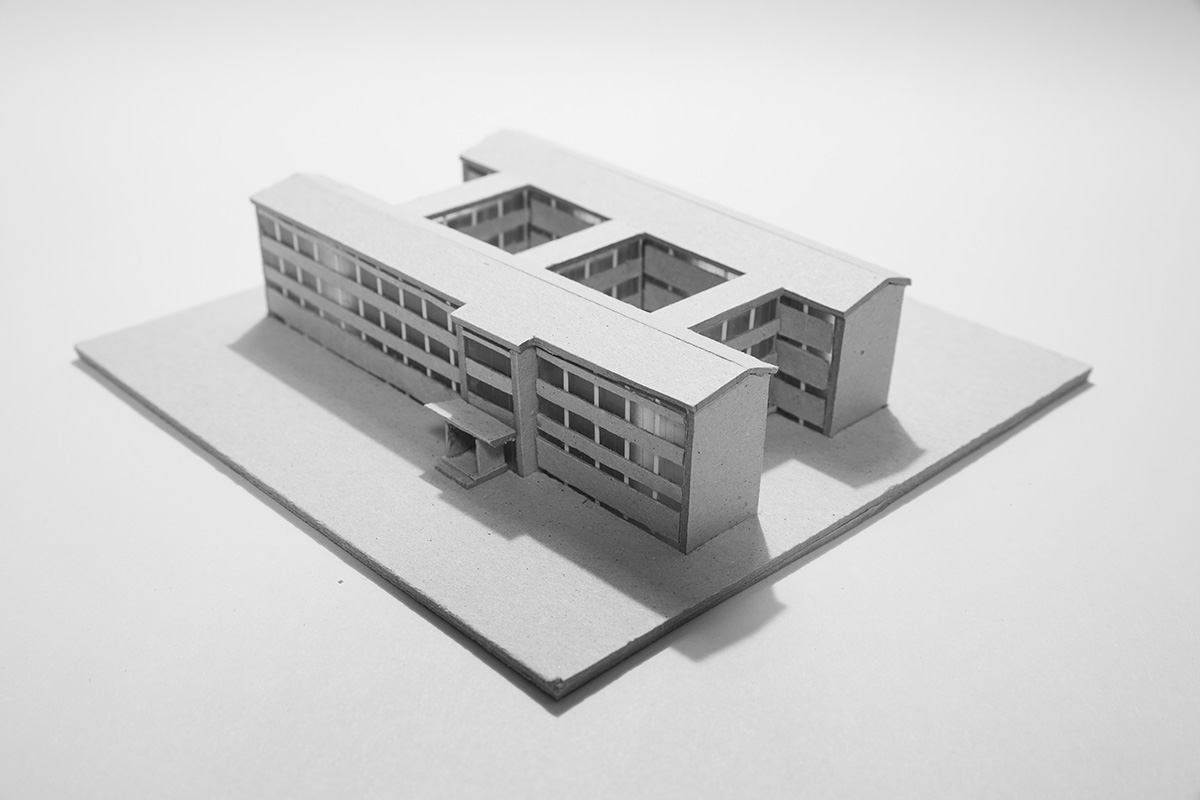

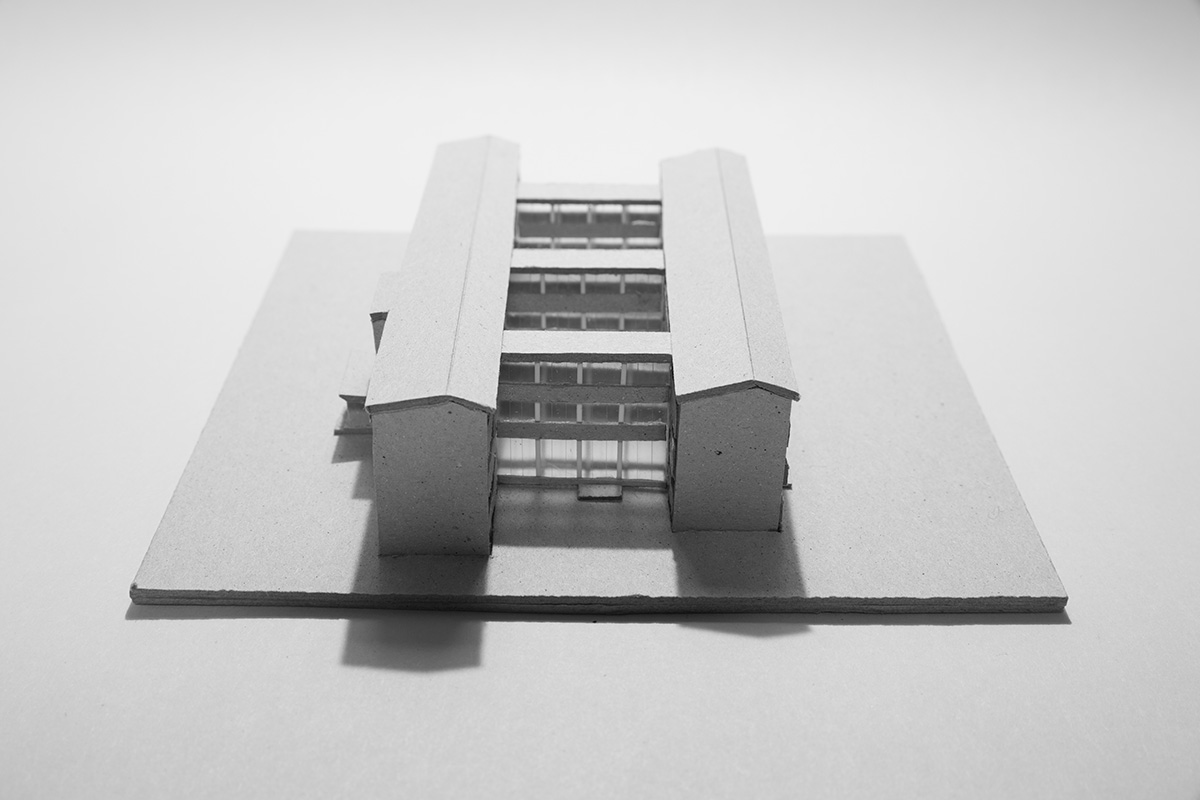

Schulbau in der DDR – School construction in the GDR

In my ongoing research I’m looking at emancipatory moments in GDR school construction. In the 1950s to 1970s education was valued as a means in transforming society. Schools and their architecture were considered a politically charged building assignment throughout different phases of history of the second German state. The school was considered to be part of a planned neighborhood which accommodated socialist every day life. The rise of new technologies, the placement of a political narrative within the Cold War and the reconciliation of family and work life were important issues. Although the authorities clung to the ideal of a centralized building type, this aim was never fully realized: regional solutions persisted and with them a variety of spatial concepts. Furthermore, the local population often participated in the planning and building process of their school.

Taking a new look at this era of school construction within the context of spatial and educational policies may help to open up “resources to inform the necessary renewal of today’s schools and universities.” as said it in a description of the project: “Education Shock. Learning, Politics and Architecture in the 1960s and 1970s” at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin. Within a conference, an exhibition, a book, films and other formats the project discusses the global significance of the education debates of the 1960s and 1970s. Curator Tom Holert put together a number of profound and diverse contributions by artists, academics and architects. I was invited to present my research in the exhibition under the heading “Prefab architecture & variety” and contribute to the conference, book and feature film.

Part of my research was published as a contribution to the issue "Moderne bildet (21/4)“ on moderne-regional.de.