25/007

Domino Architects

Architectural Practice

Tokyo

«As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts.»

«As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts.»

«As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts.»

«As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts.»

«As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

Domino Architects is an architectural practice, I Yusuke Oono, founded in 2016. We seek to explore connections between history, context, and design through both practice and theory, examining the relationships between information and material, digital and analogue, as well as high-tech and low-tech. Shaped through collaborations with diverse teams, our work spans architecture, interiors, product design, research, writing, and education.

I was born in Germany and studied architecture in Tokyo before gaining practical experience at offices in Portugal, Tokyo, and Taiwan. Eventually, I went on to establish Domino Architects.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time learning about architecture?

With an uncle who was an architectural photographer, I always had a vague interest in architecture, but as a high school student, I was more drawn to physics and initially considered pursuing theoretical physics.

But, one day after school, when I went to a bookshop and browsed through the architecture section, I came across an issue of GA (a Japanese architecture magazine) featuring Frank O. Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao Museum. I still remember the shock I felt. Even though it was just photographs, I was captivated by the complex yet beautiful spatial composition—I couldn’t imagine how it had been realised, designed, or even sketched. That moment ignited my ambition to become an architect, and I still treasure that issue of GA I bought as a high school student.

The first assignment I had after starting my architecture course at university was to “design a house for a designer living between Tokyo and Nagano, travelling by bullet train”. At the time (around 2000), such a lifestyle was unfamiliar to me, and I remember struggling to break down the theme and approach the project. Looking back, though, that challenge is what made it particularly memorable. As it happens, I actually now travel between my two homes in Tokyo and Nagano— it’s really a strange twist of fate that sees me living the very lifestyle described in that assignment that once left me stumped.

What are your experiences founding your own office and being self-employed?

One of the most enjoyable aspects of establishing my own practice has been the freedom to assemble teams of specialists and skilled craftspeople whom I respect, tailored to each project. While our office itself is not particularly large, forming these unique teams allows us to approach projects of varying scales with flexibility and in a healthy manner.

For example, in an ongoing landscape design project for an art gallery in Okinawa, we are working not only with a local architect but also with an ecologist and a gardener. In a previous project for a farm in Hokkaido, we collaborated with farmers and hunters to design structures for animals such as chickens, cattle, and horses.

It’s noticeable how different fields bring different perspectives and their own lexicon, even when dealing with the same subject. In the landscape project in Okinawa, when considering the design of the entrance path, as an architect, I simply saw it as a space for people to walk through. However, the gardener saw it as a way to let light shine linearly into the forest, illuminating the trees and creating a landscape with a facade within the forest. Meanwhile, the biologist saw it as a path that divides the environment into two groups, environment A and environment B, creating an opportunity for different ecosystems to develop. It was surprising how we each considered completely different values, even with just a single path.

As an architect, I am particularly interested in creating environments that hold value within their respective cultural contexts. Architecture has a powerful influence, and so it is all too easy to impose a singular, authoritarian vision on a project. To prevent this, we always begin by discussing how the architecture can take on a nuanced and multifaceted presence within its surroundings.

How do you remember your time as architectural employee/worker?

During my internship at an architectural office in Portugal, I was struck by how we could go home without having to work much overtime and how we took the time to enjoy lunch and coffee breaks. At the time, at least within my circle in Japan, working tirelessly—even at the expense of sleep—seemed to be considered a virtue. Back then, I had always assumed it was normal to stay until the last train, eat in a rush, and work quietly on your own. So, I was fortunate to start my career in a place where I could value my private time while still dedicating myself meaningfully to design.

While this is partly due to my own personality, I believe that maintaining a healthy and balanced way of living—and having enough mental space to appreciate one’s surroundings—has a positive impact on design work. I’m of course not denying the importance of conducting extensive studies and spend long hours on drawings, but to me, it is just as essential to take time for walks, grow plants, or travel.

The only firm I worked for after returning to Japan had, unusually for Japan, relatively early working hours. There were, of course, periods when we worked through the night for days leading up to competition submissions or major deadlines, but this was not a regular occurrence. My boss firmly believed that time outside of work should be spent on self-investment—whether by visiting galleries, reading books, or engaging in other enriching activities.

With my own practice, we consciously cultivate a similar work environment together. Play well, eat well, talk well, learn well, work well. It’s simple—I just appreciate spaces where these aspects blend naturally rather than being rigidly separated.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

Tokyo is a large city by global standards, and it doesn’t have a clear, easily comprehensible overall image. Instead, each area has its own unique culture, making it very enjoyable to observe these differences. And, of course, architecture also reflects these variations. Simply tracing the architectural features of each area on a surface level is already quite enjoyable, but unraveling the history of the topographical changes that gave rise to them makes the observation far more interesting.

Tokyo has many rivers flowing through it, and the Musashino Plateau, a highland carved out by those rivers, spreads across the city. If you focus on the topography that connects the upper and lower parts of the plateau, you’ll notice how many slopes and cliffs there are in Tokyo. The stable ground of the highlands, the well-drained land on the slopes, and the springs at the foot of the cliffs all create very different ecosystems, and the forms of architecture respond accordingly. For example, if you take a ride on the Yamanote Line, which runs in a loop around the centre of Tokyo, you can easily experience the height differences of Tokyo as you pass through tunnels and travel along elevated tracks. The architecture also shows a wide variety of responses to each of these terrains.

During the Edo period, under the command of the shogun, civil engineering works were carried out in the lowlands that spread out below the plateau. Some parts of the sea were reclaimed, and river routes were changed, leading to significant interventions in the topography. Traces of these changes can still be seen today in place names and the shapes of ponds in parks. By examining the foundations of buildings, the construction of roads, or the types of street trees planted, you can deduce whether the area was once the bottom of the sea.

I walk a lot, so when I start planning for a new project, I always take a walk around the site first (I also “walk” a lot using Street View). What kind of wind blows, what kind of plants grow, what kind of topological features it has, including man-made ones. Whether there seems to be an underground water vein flowing, what the humidity is like. I try to take as much time as possible to think broadly and vaguely about the appropriate atmosphere and impression that the building should evoke. Just as our predecessors did, I too want to respond to the history and potential of the land that the site holds.

Our projects extend beyond Tokyo and across Japan. Stretching from north to south, Japan encompasses a vast range of climates and cultures—Hokkaido and Okinawa, for instance, could not be more different. That’s why it is so important for us that the processes of observation, discovery, and design remain seamless. There is no such thing as an insignificant site. With a keen eye for observation, the distinction between “interesting” and “boring” fades away. The uniqueness of each site is what makes architecture so compelling, and as long as we continue to get new projects, I feel I can keep working with a fresh perspective.

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

Working Space – Domino Architects

Our studio is located in a residential area of Nakameguro in Tokyo. We have rented two rooms in an old apartment building and converted them into a workspace. One is used for administrative tasks and meetings, while the other, shared with a designer friend, is used for creating and storing models.

The landlady lives on the ground floor and takes care of the trees and flowers in the garden. In front of our rooms, there are large plum and jujube trees, which mark the arrival of spring and summer, respectively. Birds such as warbling white-eyes, Japanese tits, and onagadoris come and go constantly, so we never tire of watching them.

There is a river nearby, so I walk along it every day on my way to work. There are a few large parks nearby, and when the weather is nice, we have lunch at the café within one of the parks. On our bookshelf, alongside books, we also display works by artists, curiosities collected from travels, some peculiar metal parts bought from a DIY store, stones and seeds found on the street. I just have a thing for things.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

‘Architects don’t invent anything; they transform reality’, once said Álvaro Siza. I really like these words and wholeheartedly agree. Whether it’s the landscape, climate, culture, regulations, or even the relationships with neighbours, there is invariably a context woven from many threads that surround a site—much like a sheet. I want to create architecture that gently pinches at this sheet, subtly twisting it, rather than simply placing fruit on top. The area around the twist will shift slightly, but the sheet remains just that—a sheet. This is the architecture I aspire to, where continuity and transformation stand side by side.

Name your favorite…

Book/Magazine: Jikan no Hikaku Shakaigaku (translated as Comparative Sociology of Time) by Yūsuke Maki, Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges

Building: Boa Nova Tea House

Mentor/Architect: Álvaro Siza, Carlo Scarpa, Arata Isozaki, Torahiko Terada, Tomitaro Makino, Ukichiro Nakaya, Kiichi Okada, Michael Faraday, Edward S. Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, Enzo Mari, Jorge Luis Borges, and others

Building material: Potentially anything

Spatial Memory: I was watching the sunset over the Atlantic Ocean from the Boa Nova Tea House. The view was framed horizontally by long windows and a deep eave; all I could see was the sun and the sea. Caressing the underside of the eaves, the bright red light crept in and slowly filled the interior, dyeing the glossy-finished ceiling. There, the architecture acted as a filter, sifting the phenomena of the world. It’s a scene I still can’t forget.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

I’m not particularly a constructive person, so reflecting on this question is somewhat difficult for me. In other words, I’m not someone who thinks in a linear way. I believe that everything is always in a state of flux and change – including, even, my preference for breakfast.

If one were to answer the question of how architecture should change, they would need to evaluate both the past and the present. I do know it’s a question worth reflecting on, but I must admit I’m a little too caught up in all the things I’d like to try my hand at —especially since the scope of architecture, as we all know, is incredibly broad.

I would love to work on creating architectural illustrations for fantasy novels, design architecture for video games, create user-friendly furniture, and construct architecture that produces sound. I also want to design planters and insect hotels for balconies.

In that sense, perhaps being in a position where I can freely express all the things I want to do is one of the conditions for my personal utopia.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

I want to convey how important and fascinating the skill of putting thoughts into words is. Describing or documenting tangible objects or events is, of course, valuable, but the skill to translate personal feelings and insights into something that can be shared with others is just as important. The sharper our sense of verbalisation becomes, paradoxically, the more the non-verbal realm that cannot be put into words comes into focus.

Most architecture is not self-built; rather, it relies on others for its construction, so the skill of how to communicate about architecture – or how not to – significantly influences the character of the project. However, I don’t want to be misunderstood; there’s no need to be eloquent. It’s about taking an idea from within yourself and externalising it in a form that can be shared without distortion. This is a skill developed over time, honed through training.

I find it also crucial to adapt your speech and vocabulary depending on who you’re addressing. When speaking to a craftsperson, you’ll likely use more technical terms, and there may be situations where you need to connect with academic contexts. When conveying the value of a project to someone with little interest in architecture, such as a parent or relative, you would likely use entirely different language. In a broad sense, we are all multilingual. The more we sharpen this ability, the more we can enjoy being architects.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

While I enjoy sketching and model making, what I like most is 3D modelling in low resolution. In contrast to realistic, high-resolution 3D models, low-resolution models are looser and sometimes lack coherence. I’ve been using 3D CAD for nearly 20 years, gradually customising settings and shortcuts (or ‘aliases’ in Rhinoceros 3D) to suit my needs. I treat it like a well-worn set of carpentry tools, an extension of my body. When I’m modelling, I find myself somewhere between a study and a presentation. I use it in a convivial way, akin to riding a bicycle or playing a musical instrument, rather than pushing computational functions into overdrive, as can often be the case with generative design.

For about 15 years, I’ve been teaching design assignments using 3D CAD in the Architecture Department at Tokyo University of the Arts. My aim there isn’t to teach specific technical skills, but to explore the essential ideas inherent in 3D CAD as a tool, so that it can be regarded as a primitive means, like a pencil or a knife. I teach first-year undergraduates, and because they don’t have any preconceptions about 3D CAD, the results are always very interesting. It’s a rewarding class to teach, and I find it to be a great opportunity.

Do you think AI is changing the field of architecture?

In our studio, we place great importance on research as we progress through the design, and at the moment, we sometimes rely on AI for this task.

Within a project, we have AI compile lists of books and papers on topics that interest us, as well as document related subjects. For rare and old books, we might also ask for suggestions on where to purchase them. In a small team like ours, we often can’t afford to dedicate a person to such roles, so we see great potential in this approach.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

To be honest, this question was the most difficult and took me the longest to answer. There were just too many to choose from—I couldn’t possibly pick just one. But if I had to, I’d say the graphic designer Tomohiro Okazaki. He’s also a cherished walking companion.

Every single day (yes, every single one!) he shares a short animation on Instagram. Despite the remarkable quality of these videos, he doesn’t keep a stockpile prepared in advance—it’s something he does as a daily ritual, first thing upon arriving at his studio each morning. I once asked him about it, and apparently, for him, the act of making and the act of observing are practically inseparable. He said he’s not driven by a specific goal; rather, creating is a way of observing things like gravity, temperature, humidity, or even his own biological rhythm.

For him, making seems to be synonymous with playing with his environment—both internal and external. I have a lot of respect for that attitude, and it also gives me a great deal of encouragement. His work often reveals a world tinged with madness, and I believe it deserves far wider recognition.

Project 1

Bankei Farm

We are constantly intrigued by what the right distance might be between architecture and those who occupy it.

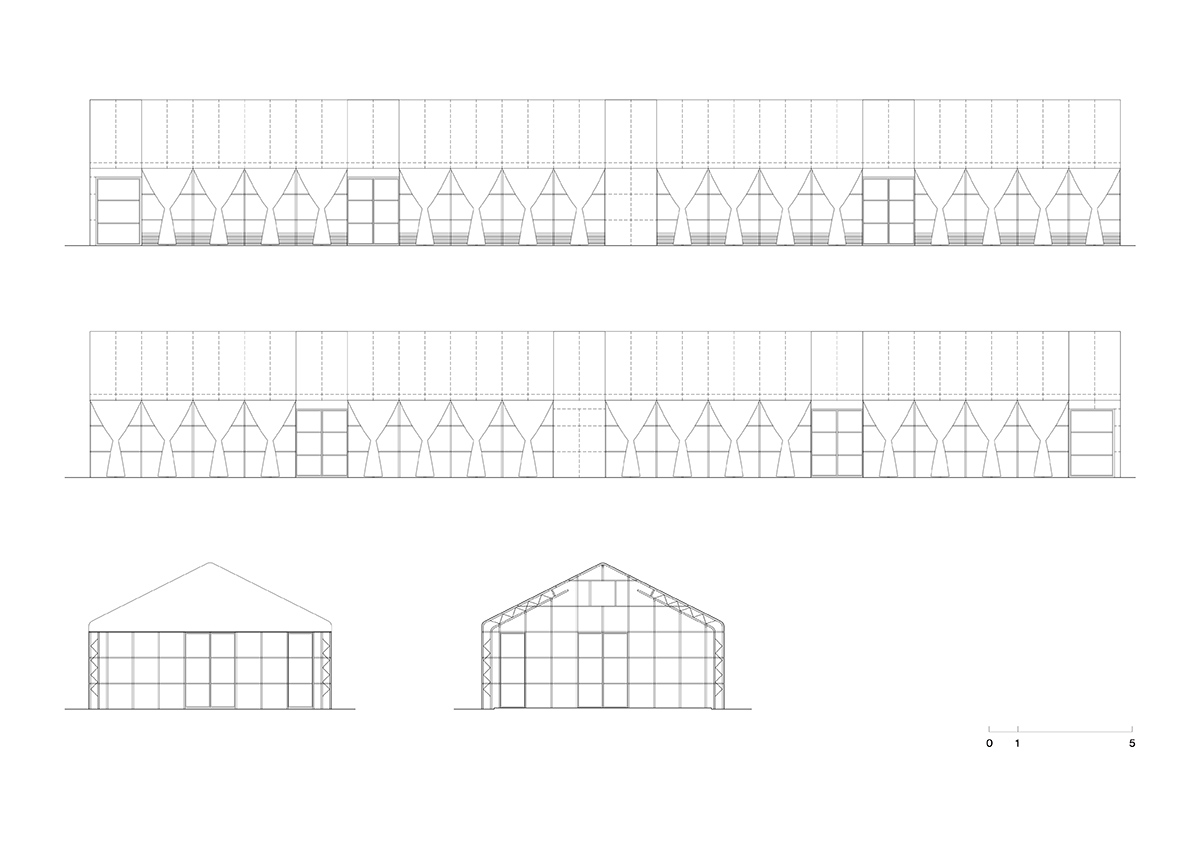

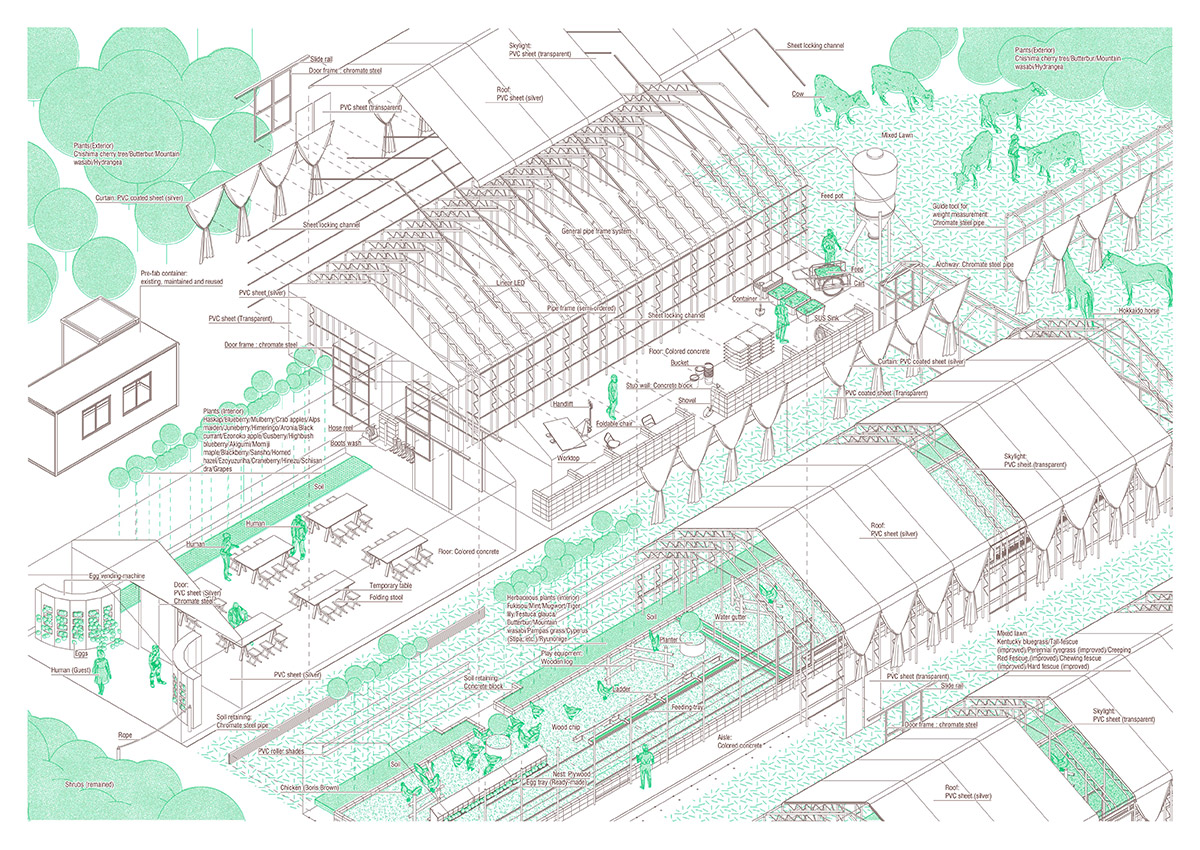

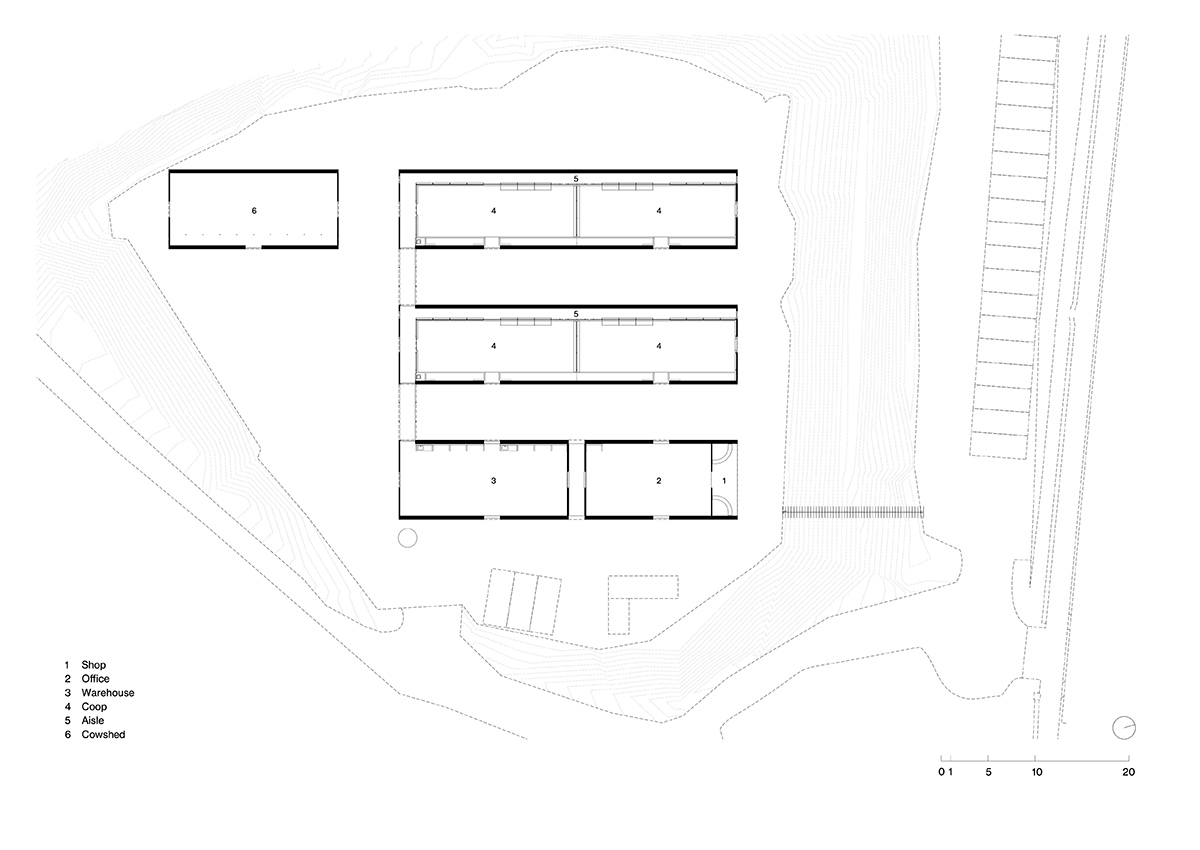

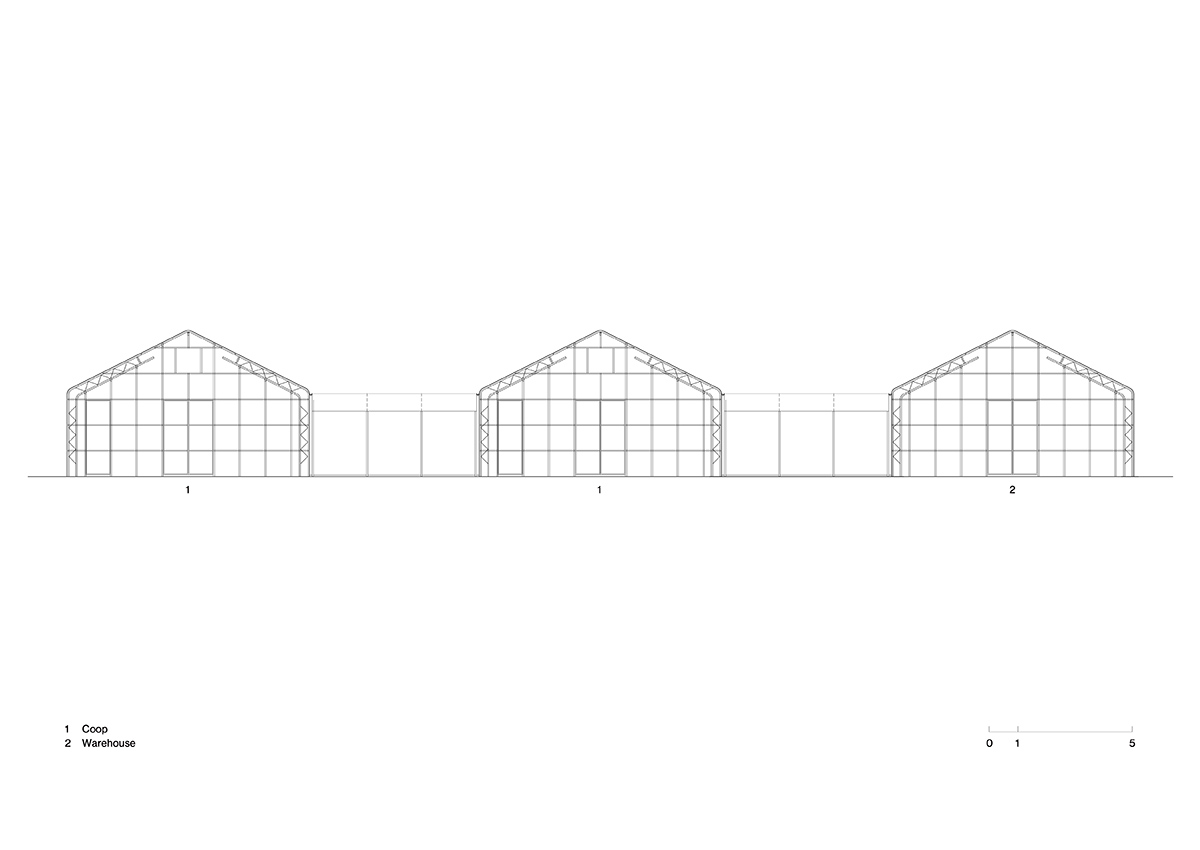

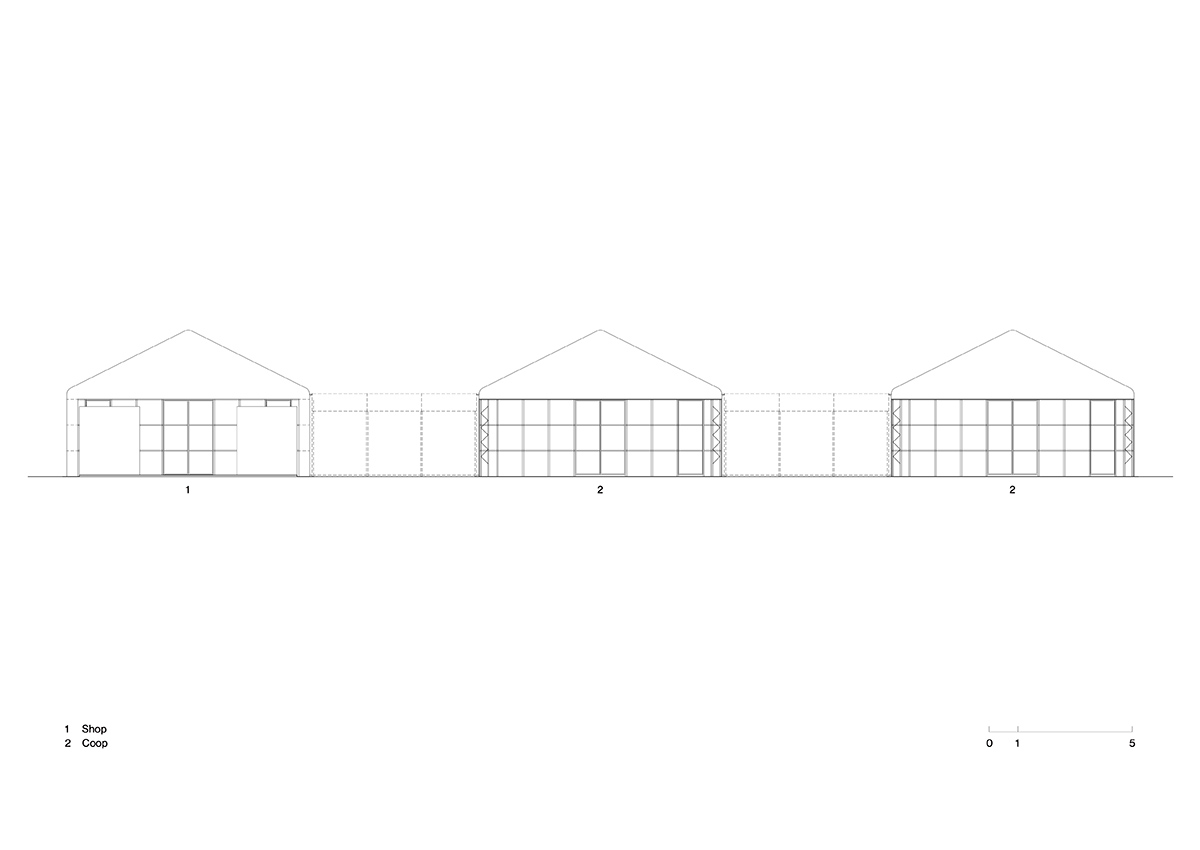

In Sapporo, Hokkaido, a 22-hectare forest in the Bankei district—just a 20-minute drive from the city center—hosts a farm run by Utopia Agriculture, a confectionery manufacturer. Initial developments included a stable, a cowshed, a chicken coop, and a small corner shop selling fresh eggs.

The functions required of a farm handling animals and plants are fundamentally simple and primitive. So, what can architecture contribute to such a place? If a cowshed or chicken coop were to be something different from the familiar, might it cause discomfort or confusion for its users? While pondering these questions during walks through the Bankei mountains, we stumbled upon a charming farm tool shed built by a local farmer.

Constructed with plastic roofing sheets and log poles, the shed was perfectly sized to house a tractor and farming tools, with garlic and onions hanging from the beams. It felt like a custom-made tool crafted by a seasoned artisan—and it felt “just right.” This fortunate encounter gave us insight into what the farm should be.

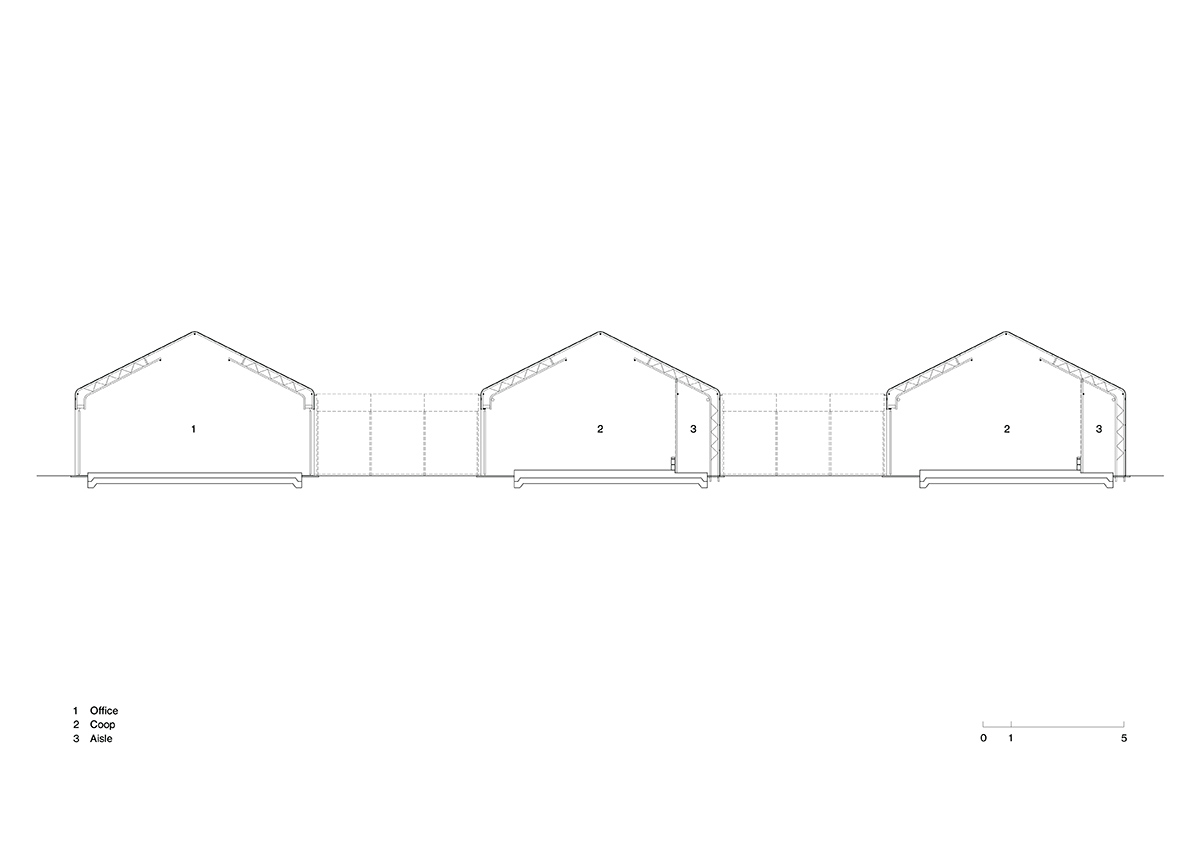

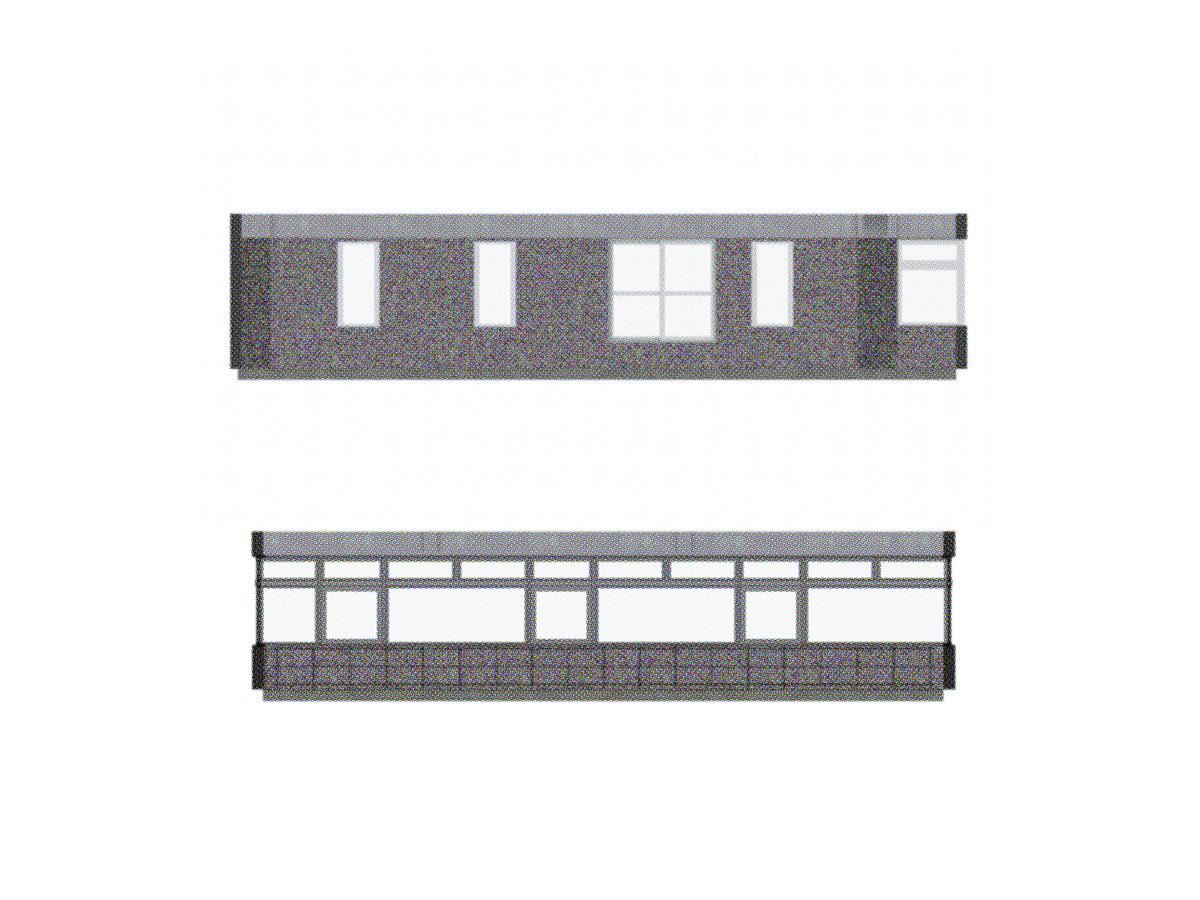

We developed a custom frame based on an existing product—an agricultural pipe house from a local Hokkaido manufacturer—which serves as the building's skeleton. With optional parts readily available at agricultural equipment stores, expanding the pipe house's functionality is straightforward, whether it involves adding openings, installing nets, or attaching fittings.

We chose silver heat-reflective sheets as the primary exterior material to reduce heat load. In summer, these sheets can be bundled like opera curtains to improve ventilation, while in winter, they can be closed for better insulation. Periodically, transparent vinyl panels replace sections of the sheets to allow sunlight in. One corner of the farm features an unmanned egg vending station, equipped with a custom-designed vending machine whose mechanism is kept as simple as possible, making it easy to repair if needed.

This farm doesn’t just produce milk and eggs; it is also an experiment in circular dairy farming, aiming to revitalise the forest ecosystem by allowing cows and horses to roam freely in the mountains. As they roam, their hooves naturally aerate the soil, promoting nutrient circulation. By feeding on overgrown vegetation like bamboo, they help the undergrowth flourish and stimulate the germination of dormant seeds, contributing to the forest's overall rejuvenation.

Attempts have also been made to raise chickens in a low-density environment that closely mimics their natural habitat. Inside the coop, vegetation zones are densely planted with a variety of native Hokkaido plants and herbs, including haskap berries, Siberian crabapple, horseradish, and Japanese knotweed. Besides their regular feed, the chickens enjoy fruits, flowers, and insects that gather around them.

Unforeseen challenges are inevitable when working with animals and plants. It was essential for the farm to have a space where people could adapt and make adjustments as needed. Through continuous refinements, we aimed to create a building that would not only become more user-friendly over time but also develop a unique character specific to this place—like a well-crafted tool.

Architecture: DOMINO ARCHITECTS

Vending Machine Design & Production: nomena

Collaborator: SEAD, Kazuma Dogin

Landscape: Kosuke Katano

Construction: Maruni-Pipehouse

Photography: Gottingham

Project 2

MIYOTA

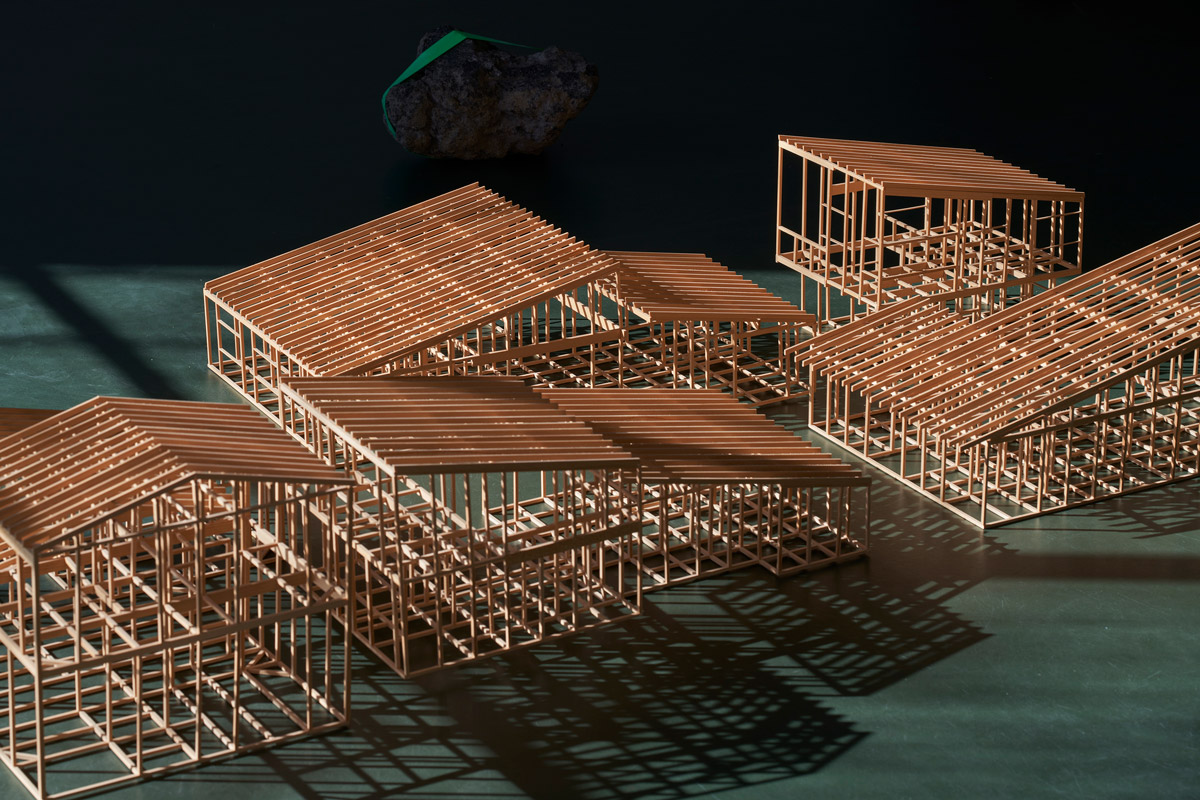

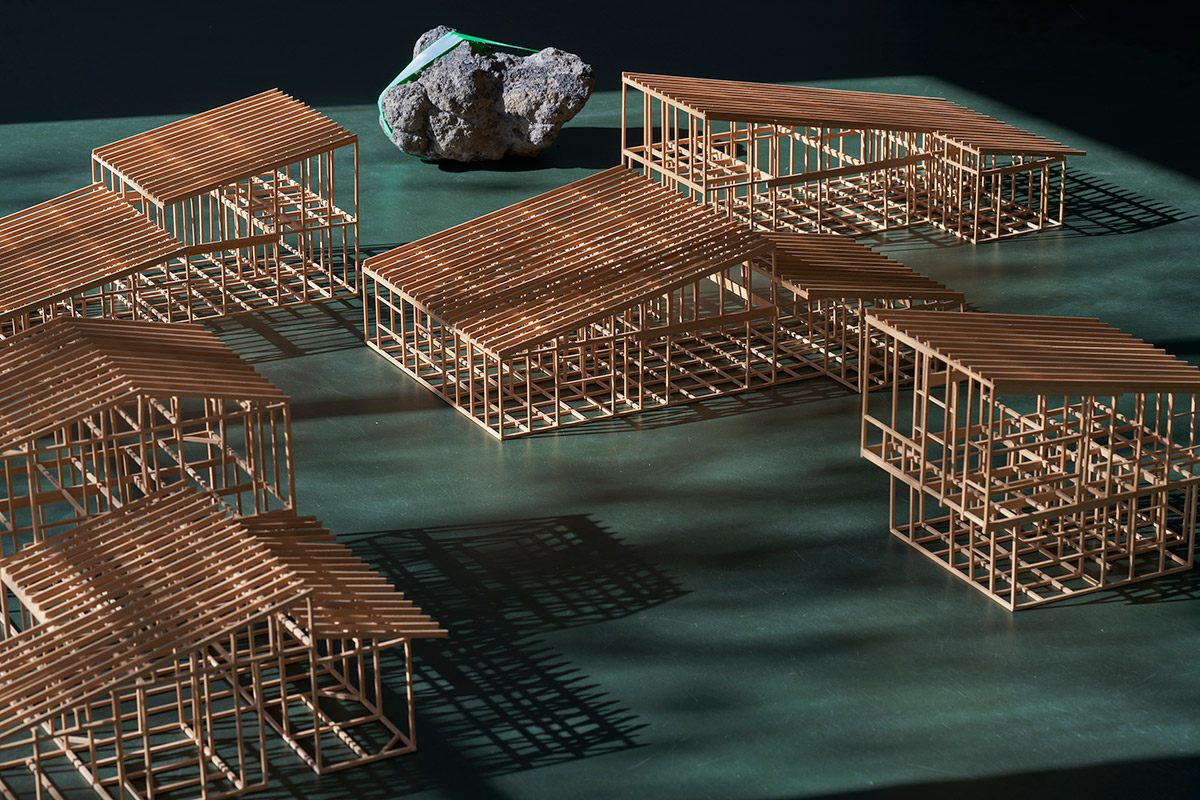

At the foot of Mount Asama in Miyota, Nagano Prefecture, five families, including my own, came together to purchase a vast, untouched expanse of land covered with Japanese red pines. From this, a plan emerged to build a house for each family, and we were invited to take part as architects.

These weren’t to be flats or co-housing units, but legally defined as five independent houses. The shared land was divided into plots, with each family owning their section.

On planning five houses at once.

Having a single designer dictate and control every decision didn’t feel right for this project. At the same time, letting each family build entirely on their own seemed like a missed opportunity. We wanted each home to reflect the unique values and lifestyles of its family, but we didn’t want the site to feel like a housing exhibition, with a random collection of unrelated show homes. Instead, we envisioned the homes as a cohesive cluster. Achieving this delicate balance meant having numerous discussions about which elements should be standardised and where flexibility could be allowed.

We first decided that, before any heavy machinery was brought in, we would carry out some preliminary thinning ourselves, set up tents, and camp on-site before any infrastructure was put in place. As for the overall plan, we took our time deciding how to arrange the houses on the site. You couldn’t ask for a more luxurious way to begin a project. Fully immersing ourselves in the environment—observing the naturally growing plants, the flow of water, the appearance of Mount Asama, the way sunlight enters, and the prevailing winds—we chose to treat the centre of the site as a large garden, with the houses arranged around it. In the shared garden, we plan to include playground equipment, a dining table, a sauna, and more. Over time, additional functions will likely be added through collective effort.

In most aspects of the building – the layout, landscaping, energy management, and so on – everyone is making their own decisions. You can really see each person's taste coming through, especially in the interiors. For example, in one of the houses, the interior is lined with cypress plywood, finished with a dusting of mica powder. When the sunset pours in through the west-facing windows, the room is bathed in a brilliant red, sparkling with light.

On the other hand, for the skeleton supporting each building, such as the columns and beams, we decided to standardise the approach to these structural elements. We also unified several exterior features, including the roof pitch, weatherproofing details, fittings, and cladding. This meant we could have a shared set of detailed drawings and specification sheets, which could be used across all the houses. That said, these exterior guidelines are not set in stone. It’s perfectly fine for anyone to add elements later, such as canopies or shelves, adapting the homes as they live in them.

In some ways, it reminds us of Ultraman’s family (a nationally famous alien superhero in Japan). Ultraman Taro has horns, Ultraman Seven has a lot of red skin, Ultraman Ace has curly sideburns, and Ultraman Zoffy has bumps on his suit. Yet, it’s immediately clear that they are all brothers, sharing the same DNA.

What’s here is a site, architecture, and a cluster of buildings, as a friend shared their impression.

A project shaped by an organic, collaborative process—neither defined by a rigid masterplan nor entirely spontaneous. The resulting landscape is remarkably supple, confronting us with diversity, tension, and a palpable sense of reality.

Architecture: DOMINO ARCHITECTS

Design & Supervision: MYTPJ

Structural Design: Tetsuya Emura

Construction: Shibadaira Kensetsu, Sanada Kensetsu, Aokiya

Photography: Gottingham

Images

Model

Project 3

HAKKO GALLERY/STUDIO

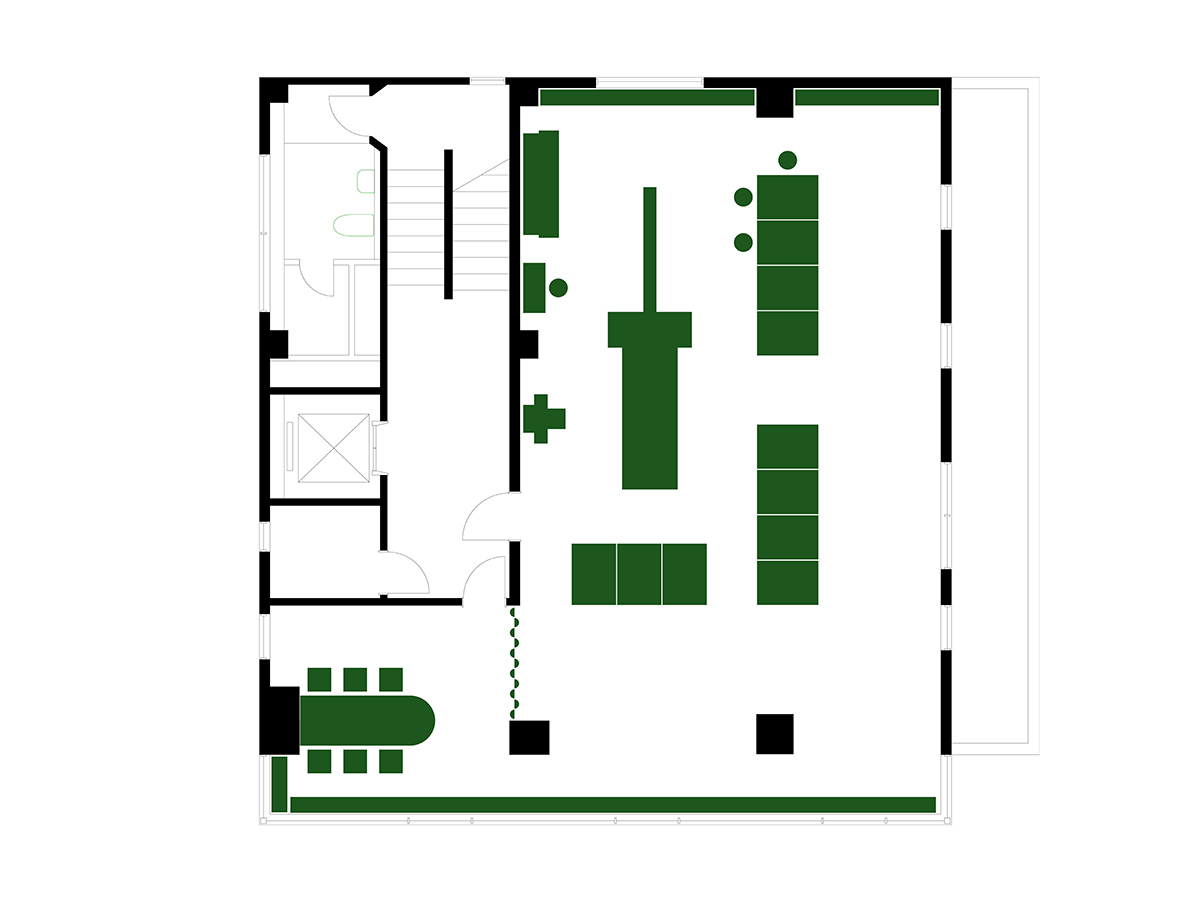

Iidabashi, Tokyo. On the top floor of HAKKO BIJUTSU, a printing company trusted by many designers and photographers, we designed a space that combines a library, gallery, workshop area, and reception room.

When thinking about the intersection between printing and architecture, certain images come to mind: woodgrain flooring, marble-like tiles, wallpaper, carpets, films, and sheets. Look around, and it’s not uncommon to find yourself surrounded by printed building materials on the floors, walls, and ceilings.

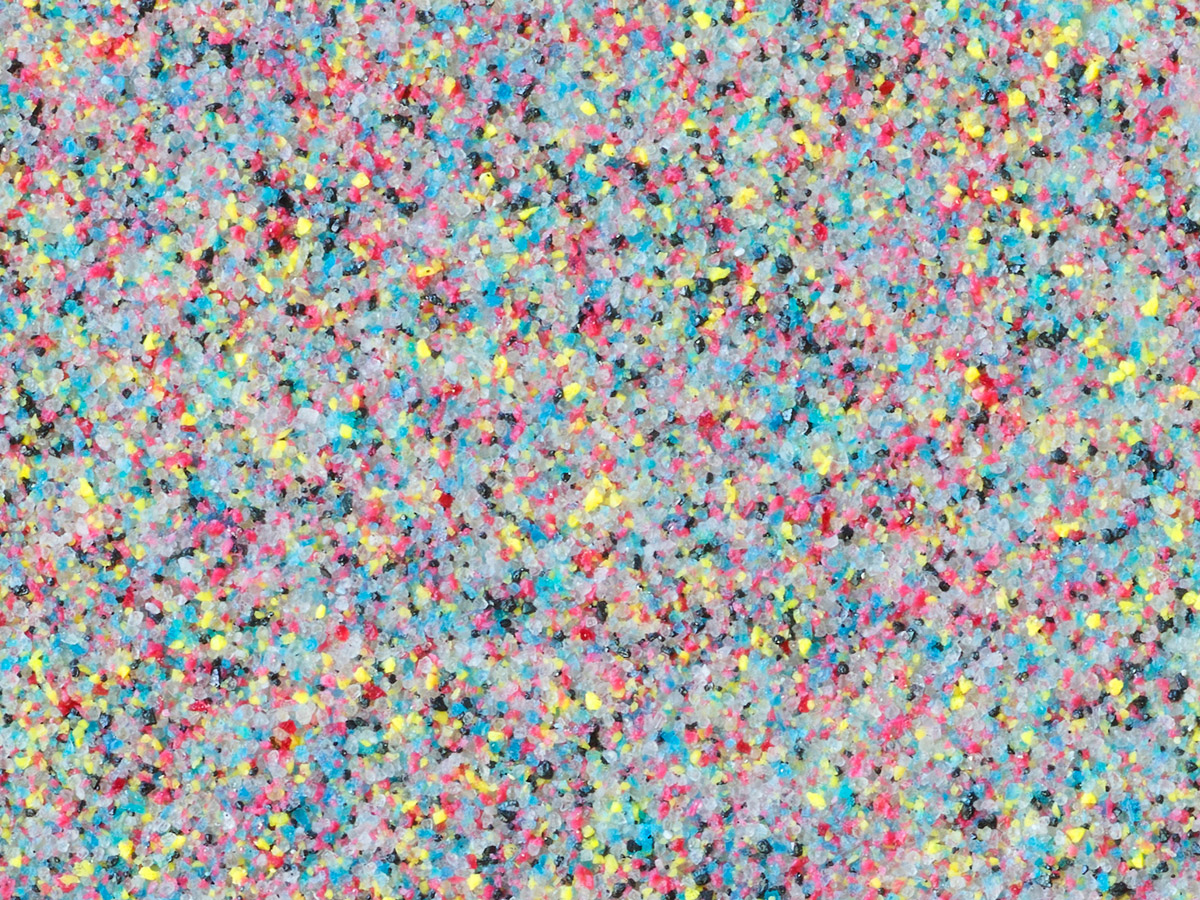

At first glance, from a distance, it’s difficult to distinguish the real from the printed. Only when you look closely do you notice the halftone dots of the four types of ink—C (Cyan), M (Magenta), Y (Yellow), K (Keyplate/Black)—and realise that it’s printed. What initially appears to be walnut or cherry wood reveals itself as a collection of colour particles.

It’s like a sensation of magnification, increasing as you peer into printed materials—much like Powers of Ten. Couldn’t we incorporate that into our design?

As the space will also be used for printing checks and colour proofs, we applied translucent film to the window glass to reduce noise and colour bleeding, and chose a neutral grey for the walls. Rather than using regular paint for the grey, we mixed plaster with powdered CMYK colours and applied it thickly with a trowel, creating a texture similar to a sand-textured wall.

For C, M, and Y, we used powdered mineral pigments traditionally used in nihonga (traditional Japanese painting), and iron sand for K. With the walls coated in iron sand, prints can be attached with magnets. As the particles of C, M, Y, and K mix, the colour gradually shifts towards grey—much like dust on the floor, made up of tangled fibres in various colours, yet appearing grey.

The impression of the room is a simple, neutral grey, but when you look closely, alongside its rough-textured surface, vivid particles of colour burst into view like fireworks. Grey serves both as the backdrop and the subject of the space. Let it shift either way depending on the scene.

To accommodate potential future changes in how the space is run, we avoided constructing new walls. Instead, we created a character for each area solely through the layout of equipment, machinery, and furniture.

The stacked bundles of paper on wooden pallets, commonly seen in printing facilities, were repurposed as display stands and work tables. Placing artwork on top of them turns the space into a gallery; once you begin working on it, you find yourself in a workshop. If the top surface gets dirty, simply peel off a layer, and it’s as good as new. Each pallet weighs roughly 400 kg, but they can easily be moved with a manual forklift, a common sight in such environments. The space allows for easy use and rearrangement with simple, familiar gestures.

We are interested in creating spaces that build upon an existing culture, as seen here, whether through colour or paper. We aimed for a space that feels as if it could have existed in a linear yet twisted reality, in a possible but slightly distorted future.

Architecture: DOMINO ARCHITECTS

Sign Design: centre inc.

Material Development: Takahiro Kai (studio arche)

Pallet Fixture Production: Karimoku Furniture

Construction: flat

Photography: Gottingham

Website: dominoarchitects.com

Instagram: @comemochi

Photo Credits: © DOMINO Architects, if not stated otherwise

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 08/2025