21/011

Elias Baumgarten

Architectural Journalist

Winterthur

“Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values.”

“Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values.”

“Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values.”

“Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values.”

“Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values.”

Please, introduce yourself…

My name is Elias Baumgarten. I’m editor-in-chief of the online magazines Swiss-Architects and Austria-Architects, run by Zurich-based PSA Publishers, which is an international network representing architects, landscape architects, interior designers, engineers, lighting designers, manufacturers and architectural photographers. Our national platforms feature extensive job boards, event calendars and, of course: online magazines. Before moving to Switzerland for an editorial internship in 2015 and joining PSA in 2019, I graduated from the University of Innsbruck (LFU).

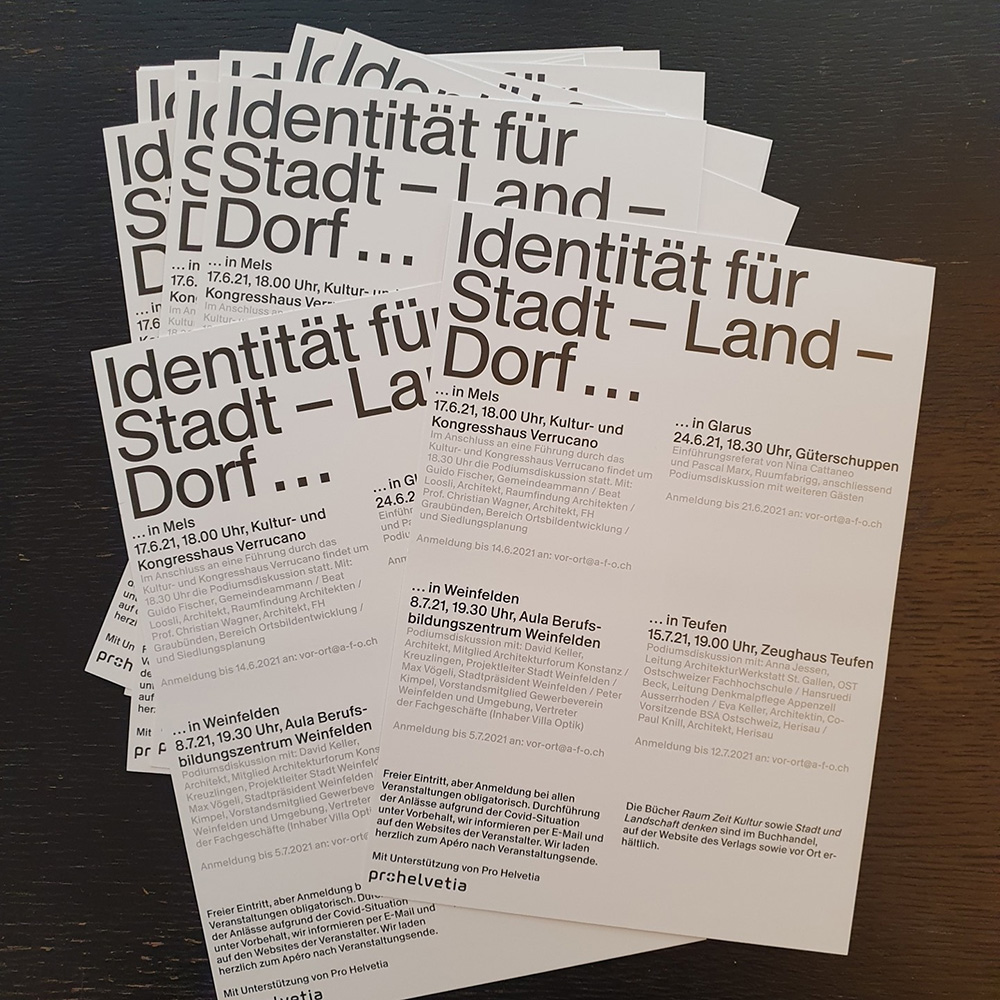

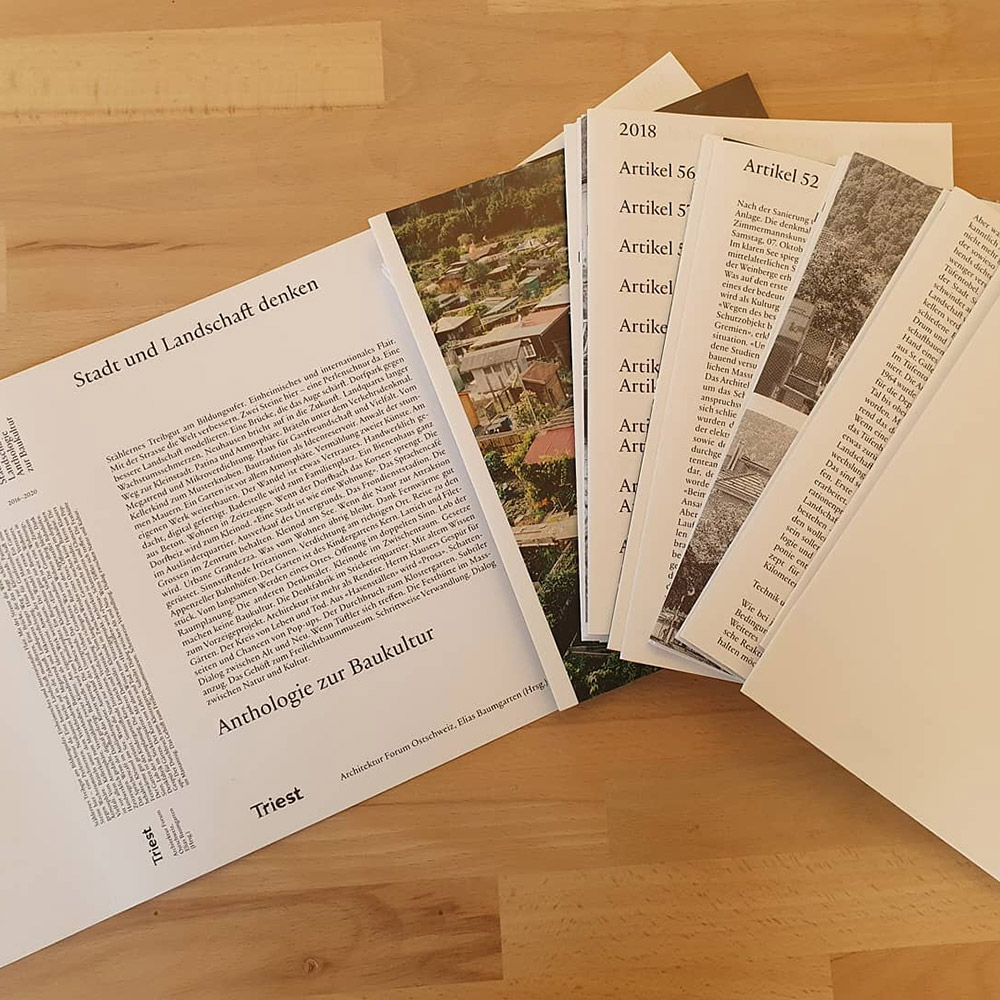

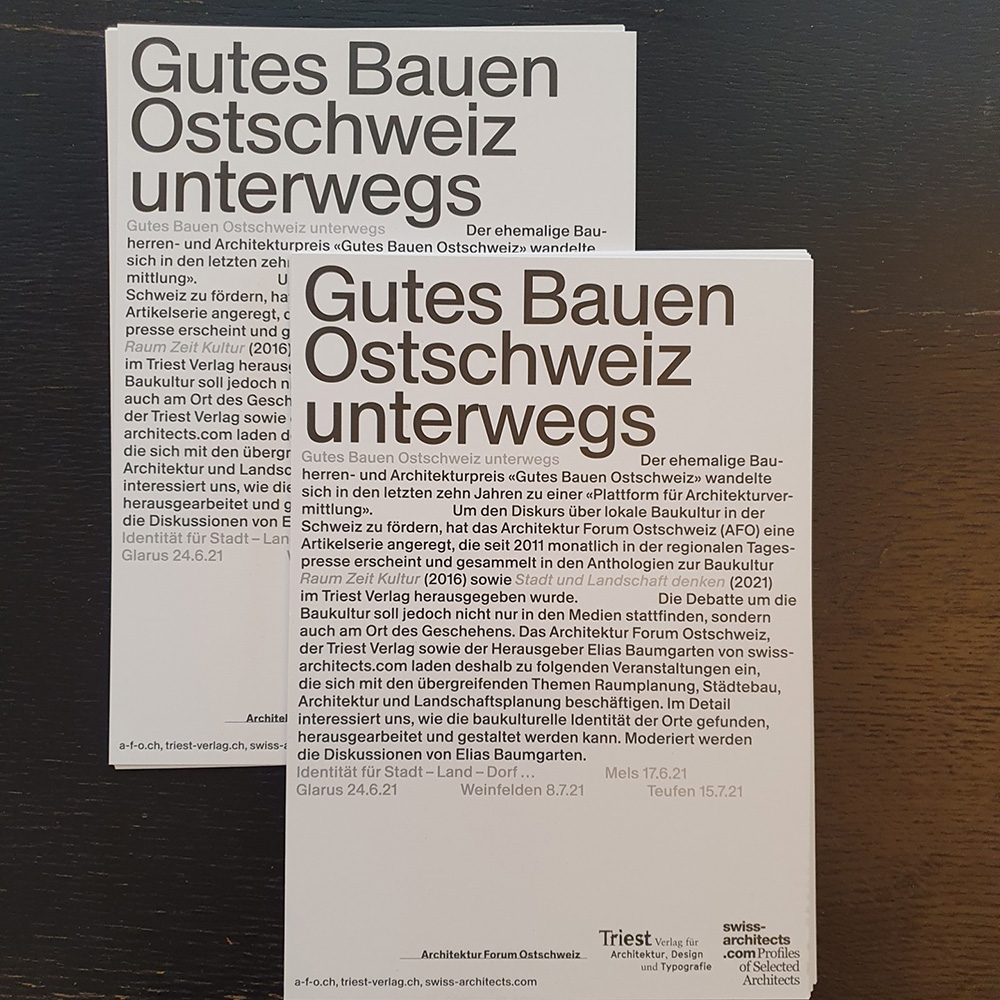

I’m originally from the Oberallgäu region, an extremely rural area in the very south of Germany, just a few kilometers away from both Austria and Switzerland. Besides working for PSA, I write articles for books and newspapers and moderate architecture events. In May, “Stadt und Landschaft denken” (“Thinking City and Landscape”), my very first book as an editor (together with Architektur Forum Ostschweiz) will be released by the publishing house Triest. And the series of events titled “Gutes Bauen Ostschweiz – unterwegs” (“Good Building in Eastern Switzerland – on the go”) sponsored by Pro Helvetia, will take place this summer.

How did you find your way into architecture and the extended field of architecture journalism and publishing?

When I was about to start working on my Bachelor’s thesis, the number of students in the studios were limited in Innsbruck and basically decided by lot. I ended up at the Institute of Architectural Theory. It proved to be a turning point for me. Over the course of two semesters, we had to come up with a book roughly comparable to an issue of ARCH+. We had weekly meetings in which we would present and discuss our research, essays and layouts, which we used to pin up on the wall like in an editorial office. That really was great fun; I enjoyed it a lot. After that experience, I focused entirely on architectural theory while pursuing my master’s degree. Meanwhile, Bart Lootsma in particular, but also his assistant professors, invested a lot of time and energy in me. They provided perfect conditions for me to build my skills, and I even started working in the department. Once I graduated, working in the field of architectural journalism and publishing was just logical to me. As already mentioned, I started by doing an internship in Zurich before then becoming an editor.

Having worked a few years now, I can say that the training I received in Innsbruck has helped me tremendously. I feel very privileged.

What is the greatest challenge you experienced in your work so far?

The biggest challenge is probably being a professional amateur. I mean: I am an architect, not a trained journalist and certainly not a Germanist. Whenever I read articles by well-trained and experienced journalists, I realize how much I need to improve my writing and storytelling skills. Recently, for example, I read a somewhat older interview with Viktor Giacobbo in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (2018) that was done by the great Daniele Muscionico, and one with Pia Zanetti in Schweizer Familie (2021) by Michael Solomicky. Both are crafted with great finesse. Their structure is extremely well thought through dramaturgically and each is perfectly tailored to the respective reader group, their level of knowledge and interests. When you read them, you feel as if the conversation is taking place right in front of you.

I think everyone can benefit a lot from paying close attention to real experts. Hopefully, openness and attention will enable you to acquire new insights or skills.

What comes to mind when you think about your diploma project? What was it about? Does it still have impact on your current work?

My diploma project is titled “Architektur, um die Architektur zu verlassen” (“Architecture made to leave Architecture”) in reference to Arnulf Rainer. It deals with transgression in architecture and examines how certain architects (Wolf D. Prix, Frank O. Gehry, Zaha Hadid and others) design and why they do so. In a way, it was an Austrian topic that fit in well with the discourse going on in the design studios of Innsbruck at time, which was—as I learned soon after—in stark contrast to the discourse here in Switzerland. It is sometimes very helpful to know two sides of a conversation. Unfortunately, I often observe that architects from both neighboring countries think of each other in clichés that do not correspond to the truth. My project was also strongly linked to philosophy and art. I read George Bataille, Jacques Derrida and Gilles Deleuze intensely. That was very inspiring.

How would you characterize the city where you are currently based as a place for practicing architecture?

Winterthur is a beautiful city with a wide variety of cultural institutions—some of them are among the most influential in Switzerland, such as the Fotostiftung Schweiz, Kunst Museum Winterthur and the Gewerbemuseum, to mention just three. Furthermore, Winterthur is home to a number of very talented architects and successful architectural practices as well as the ZHAW—a highly interesting school with very dedicated teachers. That of course is inspiring. But unfortunately, one has to say that Winterthur has recently been turning from a sympathetic city of culture, characterized by an alternative scene with many intellectuals and artists, into an increasingly vain and superficial place. So living here is steadily becoming just a pragmatic choice: Winterthur is close to Zurich, yet affordable. It is surrounded by lovely forests and a beautiful landscape typical of the Alpine foothills—you can head out of the city and within half an hour you’ll reach a place for nice training rides on your bike or long walks. But my partner and I are both very solitary people, so we would much rather live somewhere high up in the Swiss or Bavarian Alps.

It is not so much Winterthur that influences my work, but living in Switzerland in general. The Swiss architecture scene is still one of the most interesting in the world. The architecture discourse is very intense, and we have great architecture schools and a large number of specialist media. And having been hired as editor-in-chief of a magazine like Swiss-Architects, with its many readers, is also very special and of course influences my work significantly. Such opportunities are something special about Switzerland. In Germany, I most likely would not have been given a chance like this—certainly at least not this early.

What does your desk look like?

Since March 2020, my desk has been our kitchen table. It’s really cool—when I like to have a coffee or some chocolate, it’s right there. But honestly, I really miss working in the office with my colleagues. We have a great working atmosphere and lots of fun together. Based on what I hear from others, we seem to have an unusually good group dynamic.

What is architecture for you personally?

Architecture has to be and remain art. But architecture is also a manifestation of our society—its power relations, its economic and social structures, and its values. At the same time, our built environment influences not just how we live but also even the nature around us. This means that architects have an enormous responsibility, which unfortunately is becoming more and more difficult to fulfill due to changes in the construction industry and the ever-increasing complexity of our world.

Name your favorite …

Books: The relatively unknown children’s book “Das große Buch vom Räuber Grapsch” by Gudrun Pausewang is great.

Apart from that I would recommend almost any book by Swiss author Markus Werner. His sense of humor and keen understanding of people are truly unique.

A book that has made a great impression on me lately is Frank Sieren’s “Zukunft? China!”. While reading, you have to bear in mind that Sieren is a downright fan of China and not very critical at all, but his well-researched analysis, which is supported by statements from various experts, is impressive nevertheless and makes you thoughtful, maybe even pessimistic.

Magazine or daily newspaper: Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Quote: “Speak only when necessary, and even then say only half of what you think. Write only what you can endorse.” – Roberto Donetta, Ticino photographer, 1865–1932

Buildings: There are two that really impressed me: a farmhouse conversion dubbed “Birg mich, Cilli!” by Peter Haimerl, which he showed me back in 2017, and Angela Deuber’s very first project, the conversion of a medieval house in Stuls, high up in the Swiss Alps, which she invited me to visit in 2020. I had the honor to write one of the first comprehensive reviews of the latter project and publish it in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Both projects make you forget the whole world around you—lost in architecture in the best sense of the word.

How do you communicate architecture?

Within the crowded field of online journalism about architecture, we at Swiss-Architects pursue an independent approach: besides providing some news, we like to feature long, in-depth articles that focus primarily on architecture but also on art, design and culture. I especially like interviews, because I want to spotlight different opinions on current topics such as digitalization and the climate crisis. Interviews are readily accessible to readers, yet they can provide great insights into the thoughts and opinions of the people interviewed. The only downside with them is that they take a lot of time to produce—which we typically do not have. Interviews take many hours to prepare. Afterwards, the elaboration is even more time-consuming if you want to do justice to your interviewees and create a worthy stage for them.

“Eure Besten” © Nadia Bendinelli

What do you think needs to change in the field of architecture communication?

We are under a lot of economic pressure. Freelance writers often get such low fees that it makes no economic sense to invest the time needed to write in-depth articles. Many media suffer because their income from advertising and subscriptions keeps going down, which naturally limits their possibilities. Nevertheless, we journalists must not let this spoil the joy of our work. I would like us to focus more on ourselves and our work, and to try to keep the quality of our contributions as high as possible. It would also be great if, despite all the competitive pressure, we could find a way to deal with each other in a spirit of camaraderie.

How do you understand the relation of theory, practice and teaching in architecture?

Architectural theory and history are important and valuable. At the same time, they are not particularly popular. I have the impression that only a comparatively small part of the architectural profession is really honestly interested in them. One can criticize that theory in particular is elitist and sometimes lacking in topicality today. But in my work I notice that even discussions about topics like the digitalization of our discipline or the climate crisis are hardly read in comparison to the latest competition results or image-heavy project presentations. On the other hand, I also get positive feedback: teachers have told me that they assign their students to read them. And architects have written to me to express how inspiring they found our “D-A-CH-Gespräche” (which cultivates a discourse among the German-speaking countries) and that they should have been continued. We all have very different interests and are inspired by different things—and that’s a good thing. As an editorial team, you have to think carefully about what you want to invest your limited resources in.

What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

I am pessimistic. The Corona pandemic shows that we in Europe are no longer crisis-proof. Too many people give far more weight to their personal desires, needs and emotions than to the good of the community. This is worrying because perhaps even greater challenges lie ahead. Fortunately, there is now much discussion about climate change, the plundering of finite resources and the advancing destruction of the environment. Still, there is rarely any discussion about the fact that the digitalization of our society will cost jobs and that some people will fall by the wayside because there are no new alternatives for them. Not to mention the fact that Europe is lagging behind the US and China in the development of new (digital) technologies. It is easy to imagine how dangerous this mixture could be. For example, what will the consequences be if the German automotive industry ultimately ceases to be competitive in its key markets? How are we going to cope with the negative consequences of digitalization—by providing an unconditional basic income, for example—if we as a society are not economically successful?

As far as our discipline is concerned, we have to learn to really cooperate. The mentality of solving all problems ourselves is unlikely to get us anywhere in the future. In the worst case, our profession will even disappear into insignificance with this attitude. Switzerland’s NCCR Digital Fabrication is a world leader in the development of new digital processes for construction. The researchers there are currently serving as consultants to help set up a similar institution in Stuttgart, which they might otherwise actually see as bothersome and unwanted competition. I think this is the way to master the challenges of the coming decades.

If there was one skill you could recommend for an aspiring architect to pursue in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

I do not think there is a certain skill you need to work on. But there is an attitude you should develop: being an architect—or a designer, or a journalist or any professional really—is about constantly learning through your entire career. And I would advise everyone to seek to benefit from the knowledge and experience of teachers and older colleagues. So far, I have enjoyed the privilege of always having had good instructors. I have already mentioned Bart Lootsma. I also received a great basic cultural education from my former German teacher Bernd Dössinger, with whom I am still friends. And from Andrea Wiegelmann I was able to learn about publishing and, above all, how to conceive and organize architectural events, from financing to implementation.

Especially when you are still young and have finally completed your education, sometimes you don’t like being criticized or lectured so much—but it brings you a lot further.

What person or project should we look into right now?

A few weeks ago, Luigi Snozzi passed away. I think it is beneficial to look at his work and take his personality as an example—especially today, given all the challenges facing us. He had ideals, an architectural and social vision. He tried his very best to make it reality, but without putting on a big show or expressing hatred for colleagues who had other opinions. Of course the world has changed a lot since the 1970s, but I still think Snozzi makes a good role model. In view of the great challenges that confront us in the coming years—climate change, digitalization, and the aging of society, as well as, for example, the high settlement pressure exerted on our historically rich villages and cities—there is an urgent need for architects of Snozzi’s caliber, political architects that cannot be bent and that remain true to their convictions.

Project

D-A-CH-Gespräche

Swiss Architects

2020

Our “D-A-CH-Gespräche” series was a discussion format on Swiss-Architects that was intended to stimulate intellectual exchange among architects in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. From early summer to autumn of 2020, a total of five sessions were held on Skype, with three practices from each country being invited to discuss current issues with one another. These discussions were then published in written form. Everyone involved expressed themselves very openly and gave our readers a deep insight into their thoughts. We are currently discussing in the editorial team whether there could be a follow-up series.

D-A-CH-Gespräch: “Baukultur und Architekturqualität im D-A-CH-Raum”, IV Lilitt Bollinger, Stefan Marte, Max Otto Zitzelsberger

D-A-CH-Gespräch: “Architekturgeschehen im D-A-CH-Raum”, IV Peter Haimerl, Roman Hutter und Sven Matt

D-A-CH-Gespräch: “Erklären, vermitteln, verkaufen”, IV raumstation, Marazzi Reinhardt, Hein architekten

D-A-CH-Gespräch: “Die Rückkehr der Erfinder”, IV Sigrid Brell-Cokcan, Kathrin Aste, Frank Ludin, Philippe Jorisch

D-A-CH-Gespräch: “Zwischen Notlage und Chance”, IV Verena Konrad, Friederike Kluge, Meik Rehrmann, Martin Haas