24/001

Greenwashing in Design Education

An Opinion Piece by Monica Tușinean

«It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires.»

«It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires.»

«It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires.»

«It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires.»

«It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires.»

Burning Phases and Oil: Greenwashing in Design Education

In light of the reports of COP28, the topic of greenwashing as an over spanning and insidious problem woven into all aspects of modern human existence is floating back to the surface of current discourse, to the point where a warning against greenwashing on “green investments” was issued, and the COP president himself was accused of “Wikipedia greenwashing” [Stockton 2023].

In a turn of events that surprised absolutely nobody, a record number of fossil fuel, meat, and dairy lobbyists were granted access and voices at the summit [Lakhani 2023].

Meanwhile, “sustainable” has steered well into “skunked word” territory [Brewster 2022]. Frankly, the term is now more of a signifier that a conversation is about to turn into a misinformed, luke-warm take, a sort of “I’m not saying climate change isn’t real but…” of the presumably enlightened classes, rather than a genuine solution-oriented dialogue. However, unlike that one grand aunt who thinks climate change is made up because it snowed in November, the fossil lobby is aggressive and intelligent, and its tactics are affecting architecture and construction to a staggering degree [Jewell 2022]. This essay aims to raise the alarm about how greenwashing has infiltrated our way of thinking about the profession and to sketch out a potential solution.

To phrase Hanlon’s razor slightly more gently, “Misunderstandings and neglect create more confusion in this world than trickery and malice. At any rate, the last two are certainly much less frequent” [Goethe 1774]. Surely, one can attribute a great deal of deceit and malice to the lobbyists, but how can we explain (and remedy) well-meaning architects’ greenwash-speak?

The Education Issue

Before we dive into offending actors, which isn’t the scope of this conversation anyway, perhaps we can look at the beginnings: architectural education and how greenwashing discourse is seeping into the way educators and students talk about their work.

More often than not, and speaking from a decade of teaching experience, whenever architecture students introduce their first project drafts with “we wanted to design a green building” or “our aim was a sustainable project,” that is a clear indicator that those design projects will be utterly misguided. Some examples include “Integrating buildings into the surrounding natural landscape” by digging out multi-story deep holes and filling them with concrete or avoiding concrete and steel altogether but designing spaces spanning dimensions that no timber structure could plausibly handle without considerable adjustments. Not to mention cosmetic “green facades” and “nature-inspired” structures or the use of certain lightweight materials that can only be characterized as hazardous waste. Often, what we see designed in the name of a less harmful architecture is little more than a catalog of poorly understood concepts of what “sustainable” might mean, plastered onto the most offensively banal buildings. Sometimes, the green argument is used like a protection cloak to avoid critique: “Who cares if it’s unusable and ugly, it’s sustainable!” (it never really is).

While many of these misdirected concepts can and will be easily nipped in the bud by teachers, most design studios fail to address the crux of the matter: that the majority of project briefs and the employed design methods (and methodologies) have not yet been adjusted so as to generate environmentally viable solutions. On the other end of this spectrum, design projects that actively grapple with the demands of sustainable architecture as an intrinsic part of the brief seldom fall for the rhetoric fallacies of greenwashing, but those are rare and far between.

Accidental greenwashing is not a cause but a result of design thinking that is still intrinsically anachronistic: demanding and proposing the same projects, the same typologies at the same scale, the same wasteful growth, and thus, essentially, the same buildings that got us into this mess, while demanding they somehow become less environmentally destructive. Solving an issue with the same tools that created it seems paradoxical at best and wilfully obtuse if we want to be mean about it, but this is where we mostly are, I guess. Audre Lorde’s much-quoted adage “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” [Lorde 1984] hasn’t fallen on fertile ground in architecture schools.

“There is no use in placing solar panels or urban farms on top of a building, or meticulously planning a cradle-to-grave strategy, if the building has been designed in the wrong place, or its design solutions do not serve or cannot be adapted to the needs of its users“ [Nisonen and Pelsmakers 2022].

It also doesn’t exactly help that the discourse moves so fast that in order to stay relevant, architecture schools are continuously pivoting from one trending new idea to the next topic du jour and falling victim to the “red queen effect” [Bakshi 2012] : running increasingly faster to stay in place. Keeping up seems difficult enough for qualified, well-educated architects who have gathered experience outside academia, but it seems near-impossible for young students who have to simultaneously fill in and draw from a repertoire of information, references, and skills that are poorly equipped at the beginning of anyone’s architectural education (unless the parents are architects, but this is another topic altogether). Yet, paradoxically, as challenging and treacherous as these tasks may be, nobody ever fails within the systemic paradigms of the neoliberal architecture school [Hughes 2022].

If architecture education orbits around outdated requirements that contradict the state of the profession while being inundated with demands for more (more action! more solutions! more innovation!), it is no wonder that most architects and architecture students will resort to parroting soundbites or feeling discouraged to sit with a concept like “sustainability” for longer, in order to explore and understand it in depth. This “phase-burning” [Maiorescu 2023] process means emerging architects skip essential epistemic steps, perpetuating superficial narratives and practices with no solid foundation.

Naturally, a desire to simplify and introduce structure to the “tsunami of information” [Han 2024] emerges. Implementing hierarchies into intrinsically interlaced topics is a gargantuan task, and the competitive nature of academia is, in this case, a hindrance. Every faculty chair is trying to find their place at the watering hole, trying to attract grants and students’ interest, and by doing so disappointingly refuting another beloved lie: that architecture is collaborative and interdisciplinary. (Dear reader, it is not.)

This prioritization isn’t often guided by pedagogic values. Instead, its main motivation is funding and marketability, so what crystallizes is that when discussing sustainability education in architecture, the primary focus tends to be predominantly material-centric, construction-based if we’re slightly more ambitious, while design projects awkwardly tag along.

While nobody who has dived into the matter could plausibly argue that a material revolution isn’t an essential step towards an ecologically feasible shift in design and construction [Rogers 2022], and some outstanding research has been produced in recent years, perhaps primary architectural pedagogy shouldn’t rest on this topic without including it into a more nuanced approach to design education. Despite slowly steering away from defining sustainability by CO2 alone and instead acknowledging the importance of life cycles, procurement of resources, extraction, and labor issues, these interlocking aspects of sustainability still have a long way to go before being anchored in general discourse and are as of now, rarely integrated into design studios.

In the same vein, narrowing down concepts of care and recycling to only material and construction technologies is myopic and is setting us up for cultural failure in the long term. Waste reduction is not exclusive to what is left behind after construction or demolition but should also be applied to architects' resources. Aren’t we burning an awful lot of energy designing buildings nobody truly needs instead of formulating a cohesive rhetoric and a narrative [Han 2024] that will persuade clients to avoid redundant growth altogether?

This is an uncomfortable thought because most architects and researchers remain fixated on production, whether by choice or necessity, through restrictions imposed by third-party funding: producing something (anything!), out of fear that taking the search for sustainable architecture to its only logical conclusion - that we should be making (and making do with) less - will render us obsolete. Spoiler: it will not!

But to put it bluntly, an unnecessary building made from recycled timber is just greenwashing “with extra steps”[Sanchez 2017].

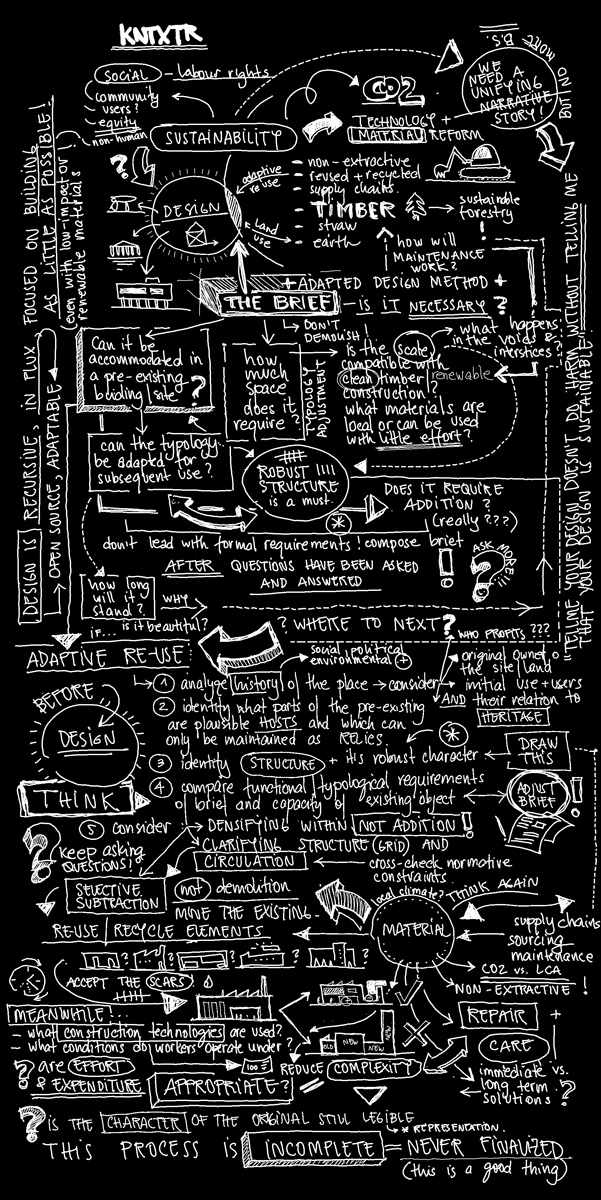

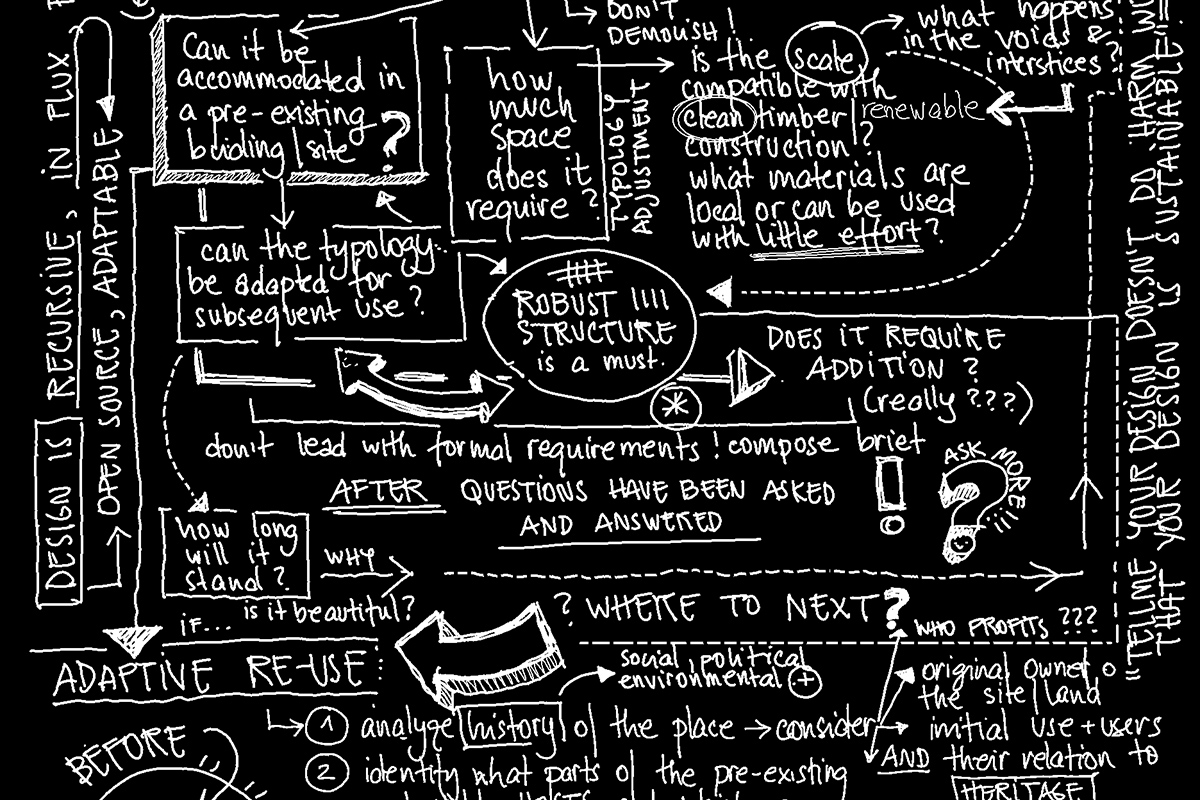

Therefore, working out appropriate design briefs that do not anchor sustainability exclusively in construction issues is essential. While ideally, all architectural education should be steered towards building less, maintaining more, and adaptive reuse projects rather than new construction, designing “new buildings” will maintain some didactic value and allow students to learn and experiment with the architect of yore’s three favorite topics: utilitas, firmitas, and sure, let’s give venustas a chance. I'm not trying to throw the baby out with the bathwater here. But we have long surpassed the era when an architect-auteur would design something they thought beautiful and could rest happily, satisfied by a job well done.

When issuing a brief, design studios should perhaps keep in mind, even if their students aren’t able to yet, that this intricate “overlapping of industries” [Ghosh 2021] and ethical conundrums we have made our profession must transform significantly in order to cause less damage. Non-extractive architecture does not naturally lend itself to any building typology or scale, and while this is a good thing, it needs to be acknowledged and engaged with. What also needs to be refuted through good design examples is the argument - made almost exclusively in bad faith – that sustainable practices are anathema to “well-designed, beautiful architecture.” (Whatever that even means).

It appears that architecture schools are buying into an erroneous dichotomy of beauty vs. sustainability and are struggling to marry didactic tradition with the architecture and construction practices the climate emergency requires. This effort to create the best of all worlds is not exactly working out.

One reason for these discrepancies may be that we still lack a fluent narrative about sustainable architecture that expands beyond the very pragmatic, the instructive, and the cautionary. This lacuna depletes architectural thinking of the fun that lives in the embodied act of designing, and by ignoring it, we are missing out on both an enjoyable process and valuable PR. Greenwashing, in return, is full of poetic stories that work as intended, asinine and superficial as they may seem to the trained eye, aiding the sales pitches of harmful construction.

Bridging this disappointing realization to design methodologies, much of the literature on sustainable architecture claims to offer solutions or to “show how to plan and build in a climate-friendly way” [Herzog 2022] while omitting to address the design process itself. Due to this, a cohesive design theory for sustainable design has not yet been constructed. Calling for a unified theory of anything is admittedly not feasible; what is bitterly missing nonetheless is a methodology to tie all these disparate approaches back to design practice. The discourse has become so complex that it has shattered into myriads of “radical” talking points, but this thinking is far from tentacular [Haraway 2016] and lacks a story.

There are plenty of fantastic built examples, to be sure, and there have been for a while now. It is, however, striking that so many publications on “building during the climate crisis” are out there, all essentially saying the same things (be radically post-concrete! save resources! build local! use the existing building stock! use renewable energy and material!), yet, most projects outside the echo chamber seem not to have gotten the memo. And to be frank, these guidelines repeated ad infinitum now seem less like a systematic plan to make anything better and more like virtue signaling and neoliberal, self-serving hot air. After all, sustainability sells.

The fixation on the material product tapers the design process to little more than an afterthought. While construction methods advance and adapt, most tasks and means of design remain firmly anchored in the modernist tradition, and again, I would argue that this is not due to malice or ignorance but out of fear. “Preservation is maddening to conservative architects because its formless aesthetics are not based on architectural presence or absence, which seems unnatural to them” [Koolhaas 2014].

Most architects are being taught to place the value of authorship over the merit of the work - and working non-invasively within preexisting bodies makes the singular writing of the new master designer awfully hard to read. Architecture in “tabula scripta” [Alkemade 2020] is then perhaps not as appealing to our profession, burdened as it is with “natalist” ideologies (Cairns and Jacobs 2014). This, in turn, instills a certain arrogance toward the “lesser” older building [Michalski 2023].

An example of haphazard focus on the correct subject without reflection from the perspective of design theory is adaptive reuse. While arguably the most sane way to go about problems that require a spatial intervention, it does not truly work when approached by the modernist principles of tabula rasa design, as Liliane Wong’s taxonomies illustrate [Wong 2023].

Renovation, reanimation, rehabilitation, and transformation are usually little more than bastardized applications of the same additive and, one would argue, if not ecologically, still culturally unsustainable practices that dominate the “Baukultur.” It is often confused for “material reuse,” a symptom of the product vs. process divide mentioned above.

Stacking new buildings on top of older ones, constructing near-parasitic extensions, and making things bigger should not be the first thought an architect has when confronted with a reuse transformation task, but this is precisely what will keep happening if we don’t learn to design “in tabula plena” [Baker-Brown 2019] and un-learn a great deal of what the “old masters” [Nisonen and Pelsmakers 2022] have taught us.

This is hard for more old-fashioned architects to understand, who will argue that operating within existing buildings is no different than when designing from scratch. This apprehension is understandable: we have all learned our so-called craft by looking at and referencing buildings almost exclusively designed and built as new objects. Even if the specific algorithm that guides the designer’s hand varies, we have all still been educated within a paradigm that is becoming rightfully obsolete. So, while we lament the state of architectural schools, few of us are willing to admit that who we need to (re-)educate first is ourselves.

As Marija Marić so poignantly put it: “The repair of architecture needs to start not from its objects, but rather its subjects - students, teachers, workers - and their relationship to the discipline itself” [Marić 2023].

Self-reflection is painful, but the alternative is half-heartedly recycling eco-awareness slogans, which, granted, is easier than recycling materials and more facile still than interrogating our deeply held beliefs about the profession. However, if we fail to consider the issue at its core, we risk all our good intentions stagnating at the exact point where true sustainability interferes with our comfort zone.

Literature:

Stockton, Ben. 2023. “Cop28 President’s Team Accused Of Wikipedia ‘Greenwashing.” The Guardian. 2023.

Lakhani, Nina. 2023. “Record Number Of Fossil Fuel Lobbyists Get Access To Cop28 Climate Talks.” The Guardian. 2023.

Brewster, Emily. 2022. “Skunked Words.” 2022.

Jewell, Bobby. 2022. “Digital Edition Archive – The Architects’ Journal.” The Architects’ Journal. 2022.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. 2014. Die Leiden Des Jungen Werther. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Lorde, Audre. 2018. Master‘s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Penguin UK.

Nisonen, Essi , and Sofie Pelsmakers. 2022. “Architectural Education In The Climate Emergency - Architectural Review.” Architectural Review. September 15, 2022.

Bakshi, Sanjay. 2012. “Run Baby Run, Says The Red Queen, Or You Will Go Nowhere.” Fundoo Professor. 2012.

Hughes, Francesca. 2022. “Failing To Fail: The Relentless Success Of The Neoliberal University - Architectural Review.” Architectural Review. 2022.

Maiorescu, Titu. 2023. Philosophie. Legare Street Press.

Sanchez, Rick. 2017. “Slavery With Extra Steps.” YouTube. May 14, 2017.

Caviar, Space. 2021. Non-Extractive Architecture. National Geographic Books.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2024. The Crisis of Narration. Polity.

Rogers, Louis, ed. 2022. Material Cultures: Material Reform.

Herzog, Andres, ed. 2022. Building Climate.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Duke University Press.

Koolhaas, Rem (2014) “Preservation is overtaking us”, GSAAP Transcripts series

Wong, Liliane. 2023. Adaptive Reuse in Architecture. Birkhäuser.

Alkemade, Floris. 2020. Rewriting Architecture.

Cairns, Stephen, and Jane Jacobs. 2014. Buildings Must Die. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Michalski, Manuel. 2023. “Tea Kitchen Conversation”. Karlsruhe, December 13, 2023.

Baker-Brown, Duncan. 2019. Re-Use Atlas. Routledge.

Marić, Marija. 2023. “The Great Repair – Praktiken Der Reparatur (DE/EN) | ISBN 978-3-931435-80-6.” 2023.