19/010

INHABIT!

Tbilisi

19/010

INHABIT!

Tbilisi

«To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values.»

«To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values.»

«To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values.»

«To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values.»

«To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values.»

Please, introduce yourself and your motivation.

My name is Thomas Ibrahim, and I am an architect and researcher at Opera Publica. My focus in architecture is the manifestation of social identity and ideology in the built environment, and the transformation of ideologically-charged Modern buildings for contemporary public use.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

In retrospect, I began my studies in architecture because of an interest in urbanism, particularly the contrast in urban development of the Southwestern United States, where I spent my childhood, and the city where I was born – Brooklyn, New York. Since studying I became more interested in the ideological and conceptual premises upon which architecture is created.

Thomas Ibrahim in front of the Technicum

Samuel Lundberg . Andreas Hermansson . Andreas Hiller

Samuel Lundberg . Andreas Hermansson . Andreas Hiller

Thomas Ibrahim in front of the Technicum

What started your interest in Soviet and post-Soviet realities? How did it lead to the current project at the Industrial Technicum? What is the pursuit of the project?

I became interested in Soviet architecture because of the image of the Palace of Rituals by Georgian architect, Victor Djorbenadze. My investigation into that particular building led me to an exploration into the dynamic relationship between identity, ideology, and architecture. As I discovered after conversations with local theorists, like Dr. David Bostanashvili, The Palace of Rituals was full of postmodern references to Georgian vernacular architecture, mythology, and tradition, and this was clearly paradoxical with the Soviet meta-ideology of total unification. The Palace of Rituals was built alongside several Late-Modern constructions which were either standard or referring to Early-Soviet Architecture: Constructivism.

My interest in the former Industrial Pedagogical Technicum began with the sculpture on the facade which was a premiere piece of Soviet iconography, referencing the so-called superman of Nietzsche and Trotsky. This would lead me to the foot of the abandoned Technicum Auditorium which was adjoined to a main block, similar to a typology that originated with Le Corbusier and refined by Brazilian architect Affonso Reidy, and others.

The abandoned Technicum Auditorium embodies the post-Soviet condition. Its monumentality demonstrates the authority of the last regime, its depleted condition speaks of the un-abating hardship post-collapse, and the reference to the revolutionary Constructivist architecture (which coincided with the emergence of the Soviet Union) are a bonafide testament to the lack of evolutionary advancementof the Soviet ideology. In The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre asserts that, “A social transformation, to be truly revolutionary in character, must manifest a creative capacity in its effects on daily life, on language and on space.” He states, later on, that the Soviet Constructivists understood that “new social relationships call[ed] for new space,” that their ambitions were halted, and ultimately they failed to make the transition to a true socialist state.

It is

- the attempt and failure of the Soviet state, as an archetype,

- the dichotomy between the initial ideals and resultant ideology, made evident in architecture,

- the lack of refinement of ideology,

- and the several ideological and post-ideological strata, which lead to the questions of how a true social-public architecture should be produced, and the form that it should take.

To work in a space of ‘failed transition’ in an epoch of new transition – and to appropriate a socialist structure with genuine social and public activity, playfully – is the beginning of our discursive response to the full context. Is architecture or the activities that it houses the subject in question in social practice? Is there potential public value present in obsolete Soviet public buildings? What steps should be taken to appropriate them?

How did you begin the project at the Technicum?

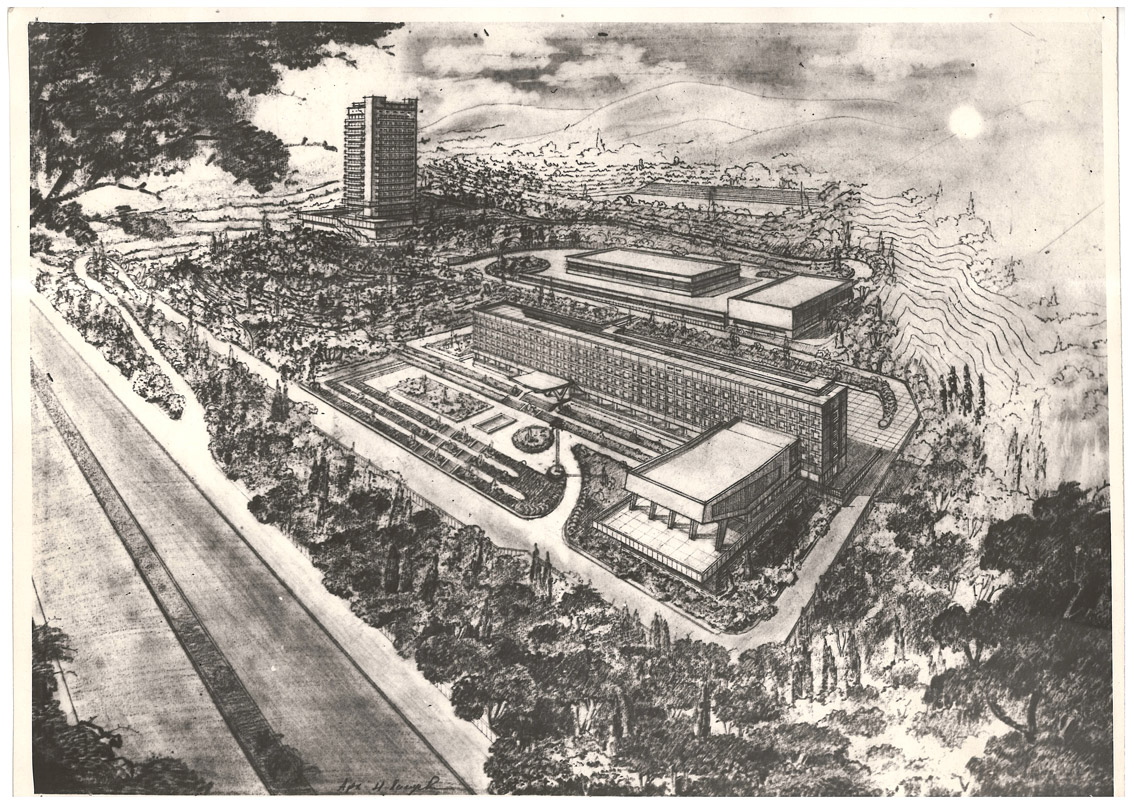

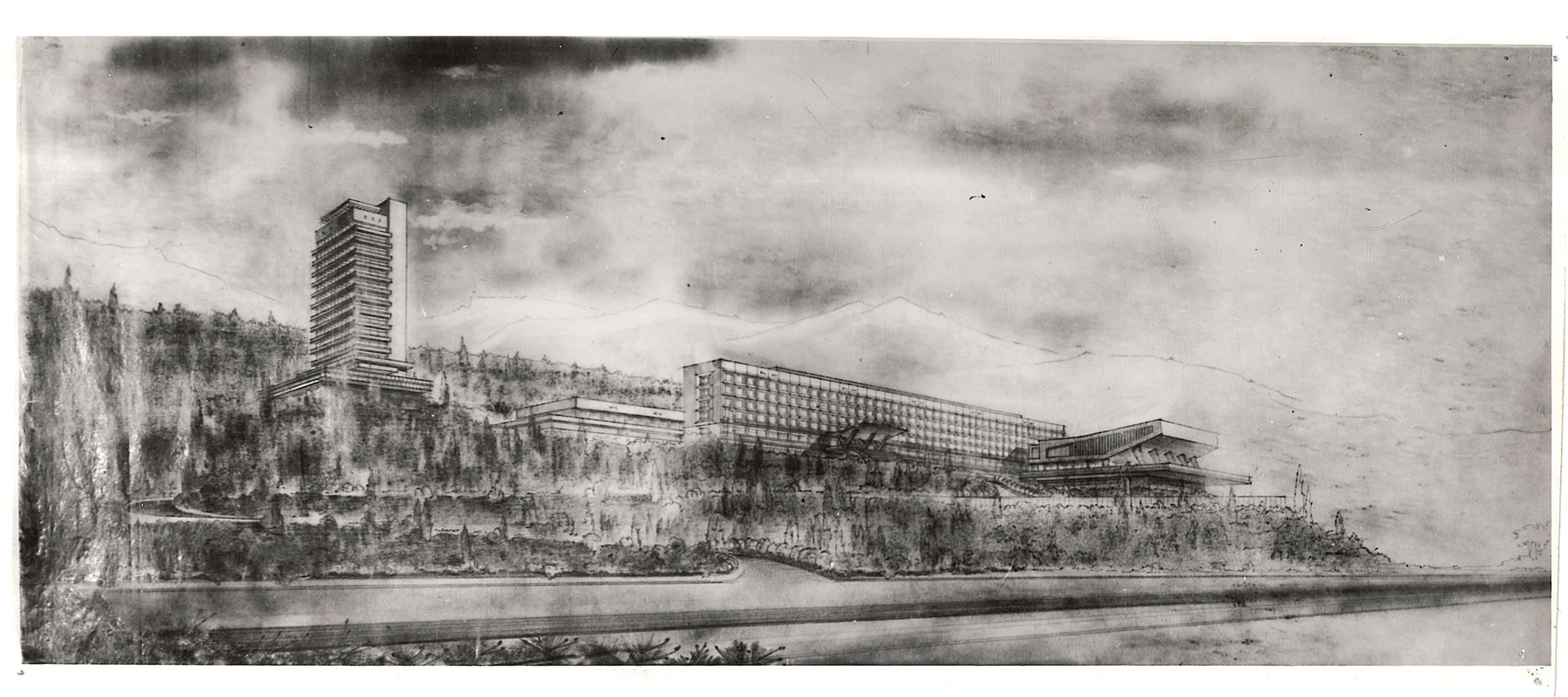

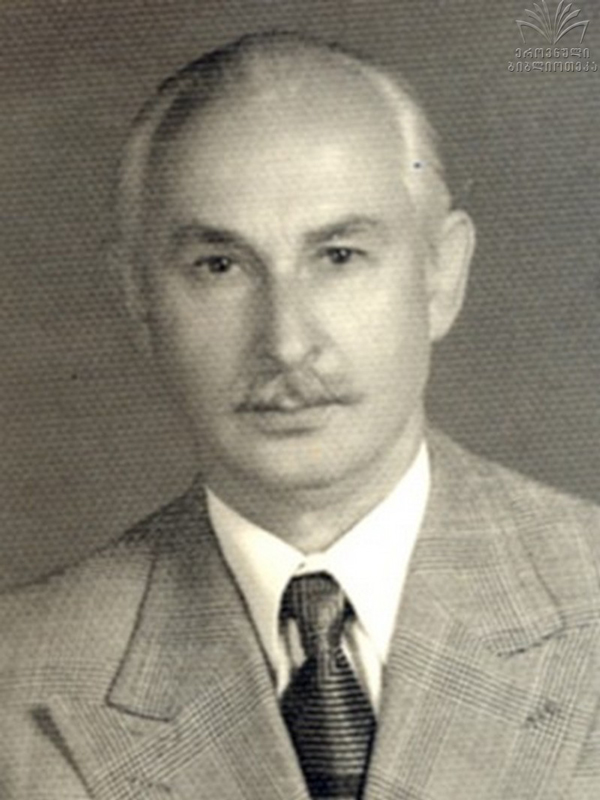

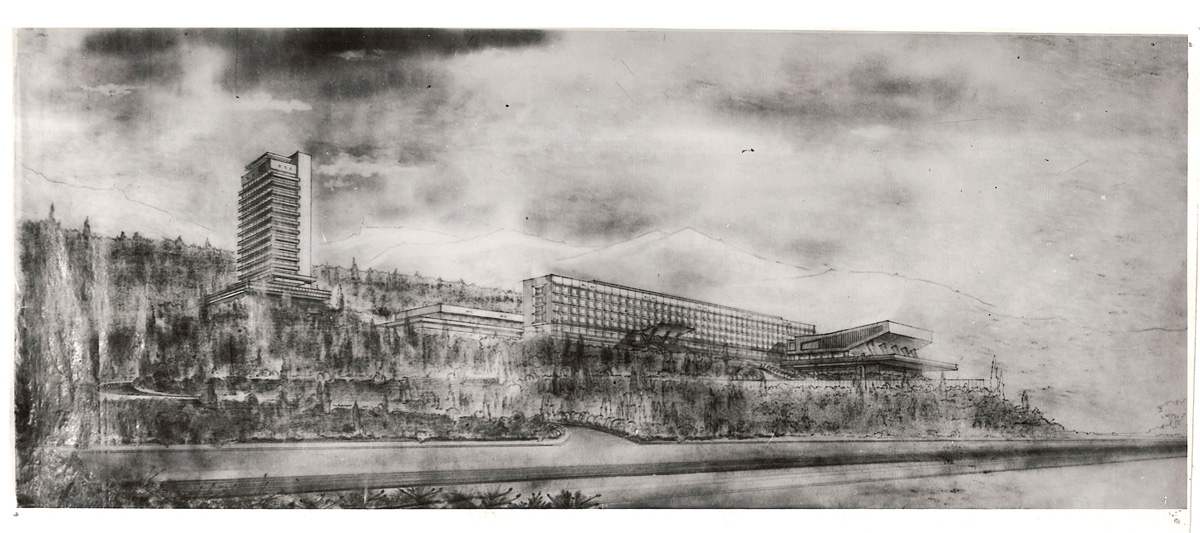

The process began in 2017, with an investigation into the history of the Technicum. I met with Lasha Mindiashvili, the grandson of the architect Nikolaz Lasareishvili and received from him the original perspective drawings of the Complex and began to survey and redraw the plans and elevations in an attempt to have the buildings and sculpture listed in the Georgian National Registry. My collaborators and I held a symposium and workshop in November of 2017 to discuss the future of the Technicum and other significant local buildings.

What started your interest in Soviet and post-Soviet realities? How did it lead to the current project at the Industrial Technicum? What is the pursuit of the project?

I became interested in Soviet architecture because of the image of the Palace of Rituals by Georgian architect, Victor Djorbenadze. My investigation into that particular building led me to an exploration into the dynamic relationship between identity, ideology, and architecture. As I discovered after conversations with local theorists, like Dr. David Bostanashvili, The Palace of Rituals was full of postmodern references to Georgian vernacular architecture, mythology, and tradition, and this was clearly paradoxical with the Soviet meta-ideology of total unification. The Palace of Rituals was built alongside several Late-Modern constructions which were either standard or referring to Early-Soviet Architecture: Constructivism.

My interest in the former Industrial Pedagogical Technicum began with the sculpture on the facade which was a premiere piece of Soviet iconography, referencing the so-called superman of Nietzsche and Trotsky. This would lead me to the foot of the abandoned Technicum Auditorium which was adjoined to a main block, similar to a typology that originated with Le Corbusier and refined by Brazilian architect Affonso Reidy, and others.

The abandoned Technicum Auditorium embodies the post-Soviet condition. Its monumentality demonstrates the authority of the last regime, its depleted condition speaks of the un-abating hardship post-collapse, and the reference to the revolutionary Constructivist architecture (which coincided with the emergence of the Soviet Union) are a bonafide testament to the lack of evolutionary advancementof the Soviet ideology. In The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre asserts that, “A social transformation, to be truly revolutionary in character, must manifest a creative capacity in its effects on daily life, on language and on space.” He states, later on, that the Soviet Constructivists understood that “new social relationships call[ed] for new space,” that their ambitions were halted, and ultimately they failed to make the transition to a true socialist state.

It is

- the attempt and failure of the Soviet state, as an archetype,

- the dichotomy between the initial ideals and resultant ideology, made evident in architecture,

- the lack of refinement of ideology,

- and the several ideological and post-ideological strata, which lead to the questions of how a true social-public architecture should be produced, and the form that it should take.

To work in a space of ‘failed transition’ in an epoch of new transition – and to appropriate a socialist structure with genuine social and public activity, playfully – is the beginning of our discursive response to the full context. Is architecture or the activities that it houses the subject in question in social practice? Is there potential public value present in obsolete Soviet public buildings? What steps should be taken to appropriate them?

How did you begin the project at the Technicum?

The process began in 2017, with an investigation into the history of the Technicum. I met with Lasha Mindiashvili, the grandson of the architect Nikolaz Lasareishvili and received from him the original perspective drawings of the Complex and began to survey and redraw the plans and elevations in an attempt to have the buildings and sculpture listed in the Georgian National Registry. My collaborators and I held a symposium and workshop in November of 2017 to discuss the future of the Technicum and other significant local buildings.

Nikolaz Lasareishvili

Nikolaz Lasareishvili

Ultimately, this effort was stymied because of a lack of interest in the preservation of Soviet Era buildings, and the sculpture on the Auditorium facade began to disappear early in 2018.

It was important to refocus efforts, and to address the conditions with a new attitude by responding to the destruction of the sculpture by redrawing the outline of the destroyed symbols, and by bringing life to the destroyed terrace.

Original perspective drawing of the Technicum, courtesy of Lasha Mindiashvili

Original perspective drawing of the Technicum, courtesy of Lasha Mindiashvili

How would you describe the relation between theory and practice? How is this relationship evident in your work?

Generally, theory and practice are dynamic terms, and the relationship between them should be symbiotic – praxis. Given the context of our project we have come up with a response based on praxis: critical realism and positive (and innovative) pragmatism, which lead to the action of inhabiting the Technicum auditorium. In an article published with Claudio Vekstein, we framed the problem as follows:

«While the city disavows the existence of the building because of its location on the periphery, distanced by its monumental placement and concealed in dense vegetation, the building simultaneously negates to identify with the city, given its foreign communist origins, which reject the local identity through ideological symbolism, causing the building to fall under the present conditions of dilapidation and neglect. Furthermore, the building is occupied by two groups that refuse each other, while the government ignores them both. The Technicum negates itself currently because it no longer holds its original identity, which was lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and furthered recently with the loss of the relief sculpture on its façade, the last trace of its cultural and ideological identity. The situation is excessively chaotic – nearly void. The question then becomes how identity can arise from almost completely depleted conditions? Identity is typically concerned with itself, and this is seen in Georgia immediately following the Soviet collapse, through the actions of the ethno-nationalists, in the attempted elimination of an abstract “other.” Another way to find identity, in void, is to adopt a new identity, which was the established national agenda during the Saakashvili regime. The first way that it ought to happen is more Hegelian, that is surpassing the contradiction: instead of simply “I am Georgian, but not Soviet,” then “I am Georgian while also something else,” identity should not be exclusive… the presence of the other, the foreign, allows for an awareness of self, which is the foundation of identity.»

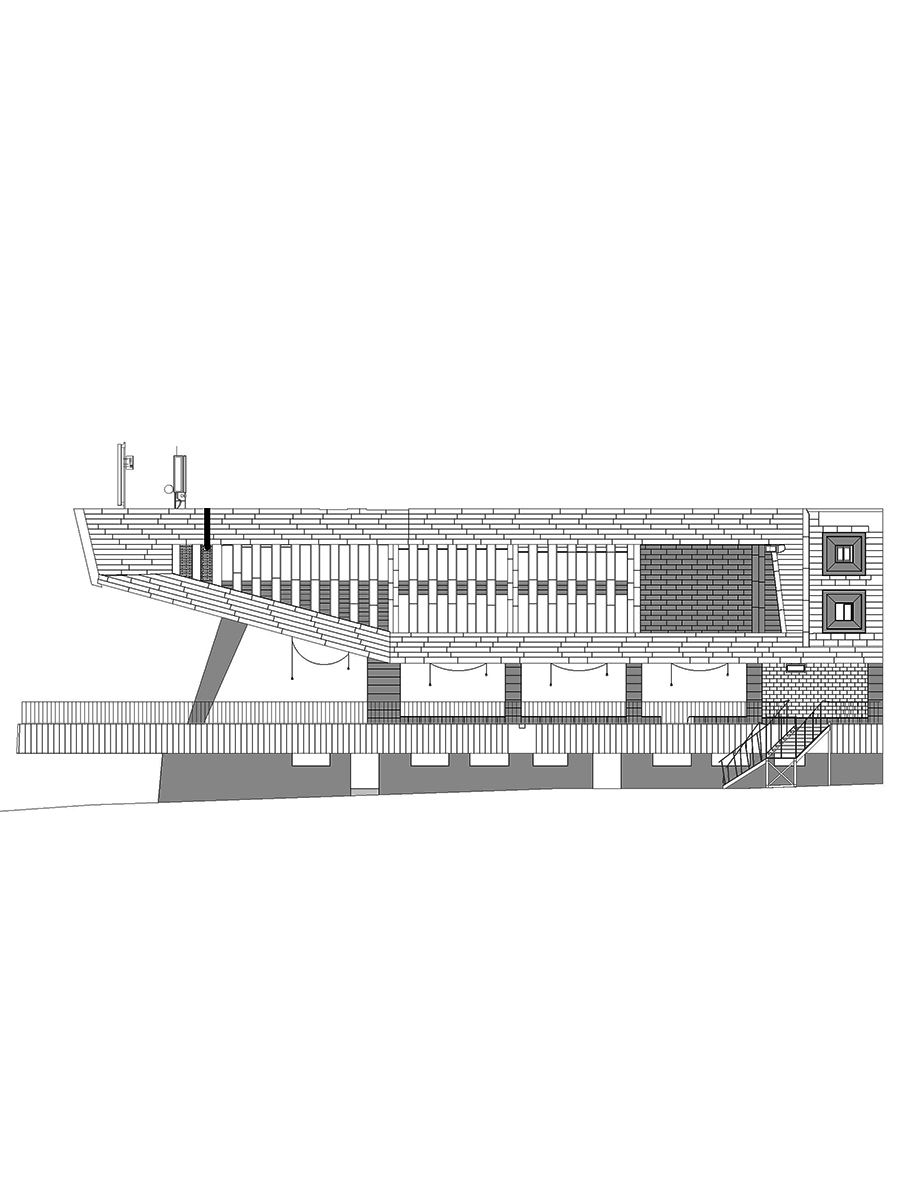

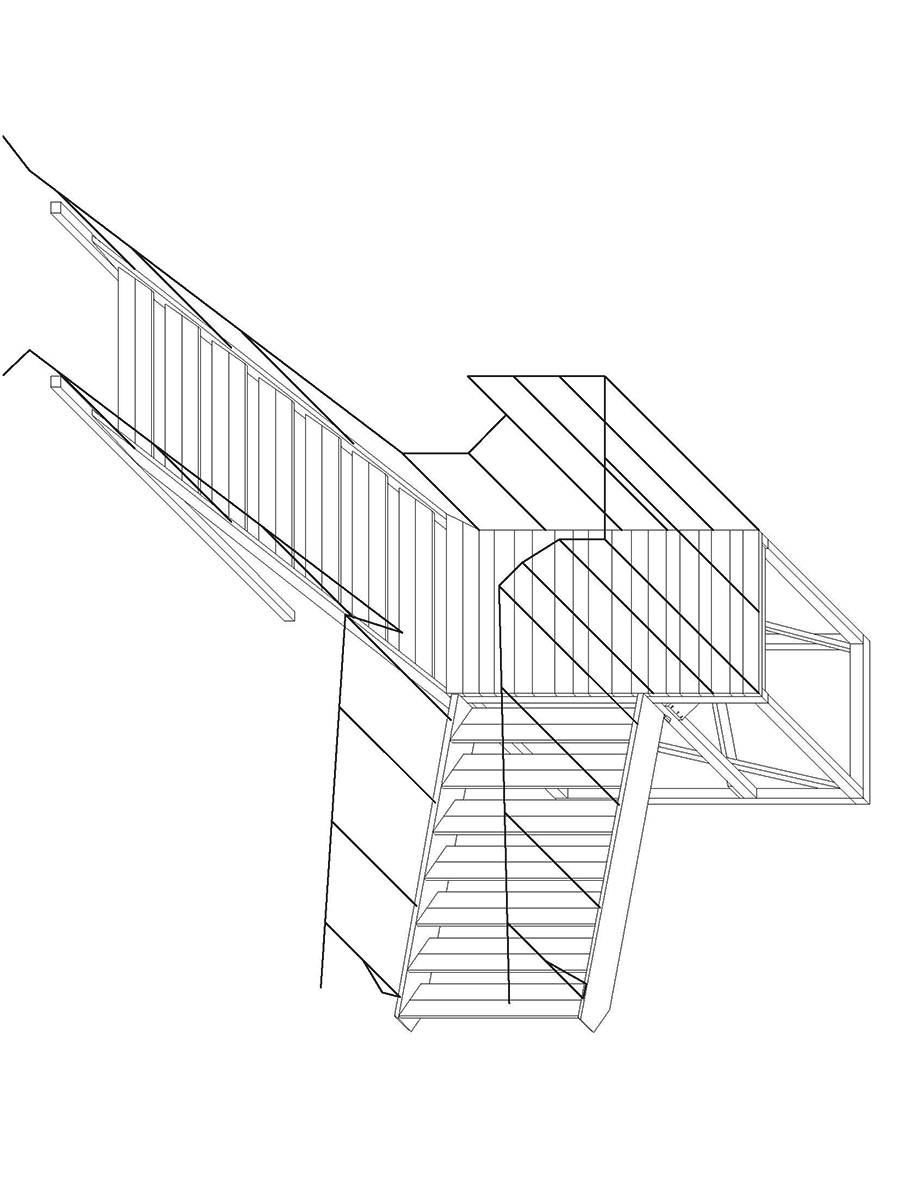

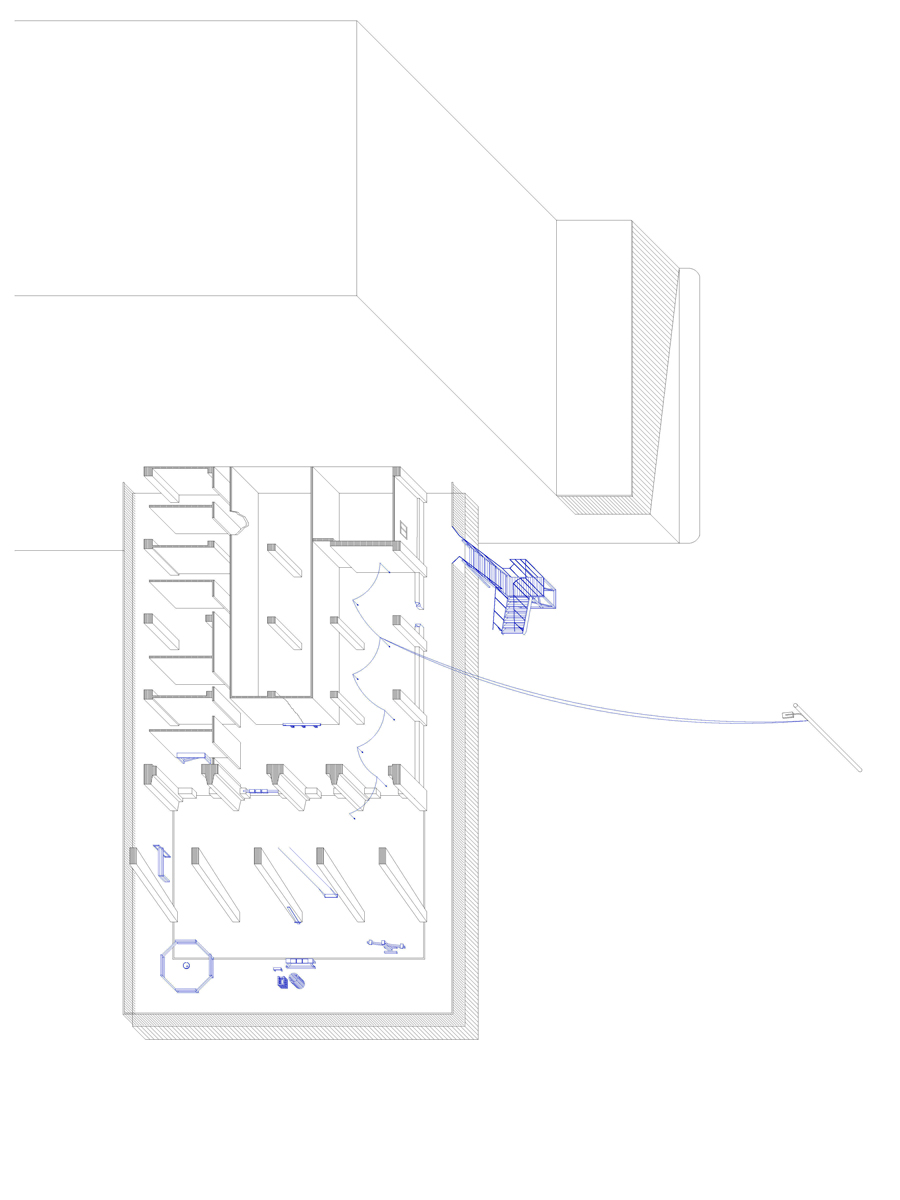

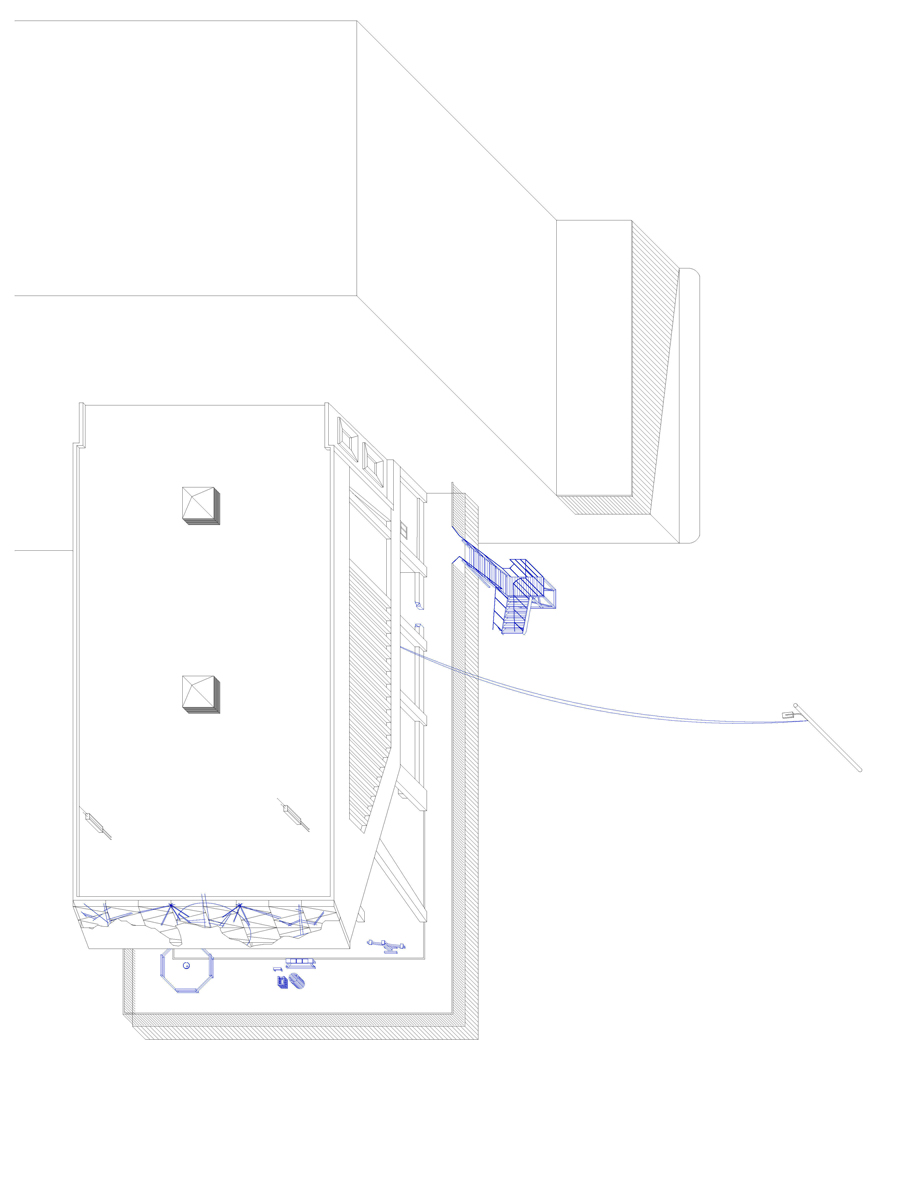

Our attitude of critical realism an attitude of seeking comprehensive understand of the context, which prepares us for the positively pragmatic response of inhabitingthe Technicum Auditorium. For us, it is not merely the use of common sense to inhabit (it is not merely a pragmatic solution), but a critical ambition to challenge the present conditions. To make the Auditorium simultaneously public and intimate, to appropriate the space for public use and to renew social spirit, is the purpose of our project at the Technicum. The first intervention that needed to happen in order to inhabit the space, was to make it accessible for the public, which we did by building the stair, and the second step was to begin furnishing the space to make it more intimate, which we did with the help of the community in the building and students from the Georgian Technical University.

What was the effect of your tactical Urban Intervention at the Industrial Technicum?

The creation of a staircase resulted in the activation of the space: the children from the building immediately appropriated the terrace as their new playground. Since the inaugural exhibition, connections have been established between the urban community and the minority community in the Technicum. The children living in the building have new role models and teachers from the local universities as a part of the most recent effort - a furniture workshop which was co-organized with Nika Gabiskiria and Mariam Dzimistarishvili. There has been a continuation of construction in and of the space.

By allowing accessibility and catalyzing the effort of appropriation, we have demonstrated a methodology for the appropriation and production of space that is social and public.

How do you communicate Architecture / Research?

With colleagues ideas are presented through hand-drawings which are made from extraction of relevant archival images. Then those drawings are refined for contractors or to find funding. In the case of appropriation, I believe that the best way to communicate and demonstrate architecture is by opening a space for interpretation by a community. It is the act of building as a community that strengthens bonds between people, and in this case it is important for the integration of the minority community that is alienated in the Technicum Complex.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

The symbiosis of buildings and people. Just as theory and practice are dynamic actors, so too are buildings and people. It is the act of building and transforming a space with people that makes appropriation real. Winston Churchill’s famous proclamation that “we shape our buildings, [and] thereafter our buildings shape us,” demonstrates that architecture is a pedagogical practice for an entire society, and that it embodies societal values. This quote, for me, does not only call into question how we shape our buildings, but who is responsible. If a space is to be truly public, it should somehow be shaped by the public.

Architecture holds a code of traditions, ideals, and history made manifest through physical sensation; the messages in that code are deciphered through the individual and communal experience of space. It is up to communities and architects to shape and reshape reality, culture, and space, to represent ideals, otherwise locality is lost.

Who is your master of architecture?

In order to learn architecture as a discipline and set of ideals, it is important to have a master. I have been fortunate to have Claudio Vekstein as my master in architecture, because his work is both disciplinary and focused on the public welfare and development, while his methodology is derived from the local customs of a place.

What does your desk / working space look like?

I recently cleared it … but it was a local, improvised studio.

The walls were covered with archival images from the occupied territories and investigative sketches of the local vernacular architecture and Modern buildings. My desk had several reference books open, and was the place of discussions with my collaborators, multi-media artist Gio Sumbadze and Georgian architect, Givi Machavariani.

What has to change in the Architecture Industry?

How do you imagine the future?

To reference Henri Lefebvre again, in the Production of Space, he discusses early in the text that there is a discontinuity between the scales of Modern reality, and this has yet to be addressed in contemporary practice. As he asserts, architects deal with ‘habitat’, urbanists with town and city planning, and economists with regional, continental or worldwide planning, with no theoretical intersection between the scales of these realities.

Perhaps the question extends beyond architecture, and architecture is merely a single implication of a much larger ideological void. Perhaps architecture should move away from being merely an industry, and more towards its humanistic roots as a discipline.

To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values. Will we continue to develop society according to the 20th-century archetypes? Will we acknowledge the shortcomings of the last century and develop more human cities? My hope is that the future will allow us to shape reality, and not just consume it.

How would you describe the relation between theory and practice? How is this relationship evident in your work?

Generally, theory and practice are dynamic terms, and the relationship between them should be symbiotic – praxis. Given the context of our project we have come up with a response based on praxis: critical realism and positive (and innovative) pragmatism, which lead to the action of inhabiting the Technicum auditorium. In an article published with Claudio Vekstein, we framed the problem as follows:

«While the city disavows the existence of the building because of its location on the periphery, distanced by its monumental placement and concealed in dense vegetation, the building simultaneously negates to identify with the city, given its foreign communist origins, which reject the local identity through ideological symbolism, causing the building to fall under the present conditions of dilapidation and neglect. Furthermore, the building is occupied by two groups that refuse each other, while the government ignores them both. The Technicum negates itself currently because it no longer holds its original identity, which was lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and furthered recently with the loss of the relief sculpture on its façade, the last trace of its cultural and ideological identity. The situation is excessively chaotic – nearly void. The question then becomes how identity can arise from almost completely depleted conditions? Identity is typically concerned with itself, and this is seen in Georgia immediately following the Soviet collapse, through the actions of the ethno-nationalists, in the attempted elimination of an abstract “other.” Another way to find identity, in void, is to adopt a new identity, which was the established national agenda during the Saakashvili regime. The first way that it ought to happen is more Hegelian, that is surpassing the contradiction: instead of simply “I am Georgian, but not Soviet,” then “I am Georgian while also something else,” identity should not be exclusive… the presence of the other, the foreign, allows for an awareness of self, which is the foundation of identity.»

Our attitude of critical realism an attitude of seeking comprehensive understand of the context, which prepares us for the positively pragmatic response of inhabitingthe Technicum Auditorium. For us, it is not merely the use of common sense to inhabit (it is not merely a pragmatic solution), but a critical ambition to challenge the present conditions. To make the Auditorium simultaneously public and intimate, to appropriate the space for public use and to renew social spirit, is the purpose of our project at the Technicum. The first intervention that needed to happen in order to inhabit the space, was to make it accessible for the public, which we did by building the stair, and the second step was to begin furnishing the space to make it more intimate, which we did with the help of the community in the building and students from the Georgian Technical University.

What was the effect of your tactical Urban Intervention at the Industrial Technicum?

The creation of a staircase resulted in the activation of the space: the children from the building immediately appropriated the terrace as their new playground. Since the inaugural exhibition, connections have been established between the urban community and the minority community in the Technicum. The children living in the building have new role models and teachers from the local universities as a part of the most recent effort - a furniture workshop which was co-organized with Nika Gabiskiria and Mariam Dzimistarishvili. There has been a continuation of construction inandofthe space.

By allowing accessibility and catalyzing the effort of appropriation, we have demonstrated a methodology for the appropriation and production of space that is social and public.

How do you communicate Architecture / Research?

With colleagues ideas are presented through hand-drawings which are made from extraction of relevant archival images. Then those drawings are refined for contractors or to find funding. In the case of appropriation, I believe that the best way to communicate and demonstrate architecture is by opening a space for interpretation by a community. It is the act of building as a community that strengthens bonds between people, and in this case it is important for the integration of the minority community that is alienated in the Technicum Complex.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

The symbiosis of buildings and people. Just as theory and practice are dynamic actors, so too are buildings and people. It is the act of building and transforming a space with people that makes appropriation real. Winston Churchill’s famous proclamation that “we shape our buildings, [and] thereafter our buildings shape us,” demonstrates that architecture is a pedagogical practice for an entire society, and that it embodies societal values. This quote, for me, does not only call into question how we shape our buildings, but who is responsible. If a space is to be truly public, it should somehow be shaped by the public.

Architecture holds a code of traditions, ideals, and history made manifest through physical sensation; the messages in that code are deciphered through the individual and communal experience of space. It is up to communities and architects to shape and reshape reality, culture, and space, to represent ideals, otherwise locality is lost.

Who is your master of architecture?

In order to learn architecture as a discipline and set of ideals, it is important to have a master. I have been fortunate to have Claudio Vekstein as my master in architecture, because his work is both disciplinary and focused on the public welfare and development, while his methodology is derived from the local customs of a place.

What does your desk / working space look like?

I recently cleared it … but it was a local, improvised studio.

The walls were covered with archival images from the occupied territories and investigative sketches of the local vernacular architecture and Modern buildings. My desk had several reference books open, and was the place of discussions with my collaborators, multi-media artist Gio Sumbadze and Georgian architect, Givi Machavariani.

What has to change in the Architecture Industry? How do you imagine the future?

To reference Henri Lefebvre again, in the Production of Space, he discusses early in the text that there is a discontinuity between the scales of Modern reality, and this has yet to be addressed in contemporary practice. As he asserts, architects deal with ‘habitat’, urbanists with town and city planning, and economists with regional, continental or worldwide planning, with no theoretical intersection between the scales of these realities.

Perhaps the question extends beyond architecture, and architecture is merely a single implication of a much larger ideological void. Perhaps architecture should move away from being merely an industry, and more towards its humanistic roots as a discipline.

To think about the future of architecture, is to think about the future of the whole of humanity and the future of human values. Will we continue to develop society according to the 20th-century archetypes? Will we acknowledge the shortcomings of the last century and develop more human cities? My hope is that the future will allow us to shape reality, and not just consume it.

Project