23/011

Iris Reuther

Director of spatial planning

Bremen

«This next generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future.»

«This next generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future.»

«This next generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future.»

«This next generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future.»

«This next generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future.»

Please, introduce yourself…

My name is Iris Reuther. I studied architecture in Weimar during the 1980s, where I subsequently earned my PhD. In Leipzig in 1992, a colleague and I founded our own firm concentrating on urban projects; 20 years later I began working as a freelance architect, focussing on conceptual urban development, process design and urbanism. Following a professorship in urban planning at the University of Kassel, I have worked as the director of spatial planning and design for the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen since 2013.

Portrait Iris Reuther – © SKUMS

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind when you think back about studying architecture at HAB Weimar (today Bauhaus-Universität Weimar)?

This was initially in opposition to the work of my parents, who were biologists and involved in nature conservation. I developed a penchant for visual art early on, would do a lot of sketching in my childhood town and often occupied myself with maps and atlases. This led to me applying to study architecture in Weimar after passing an artistic aptitude test. The 1980s were an exciting time for the city and the surrounding area, which saw an examination of the Bauhaus, international postmodernism and the general condition of the historic old towns of Weimar, Erfurt and Leipzig as well the industrial landscapes around Bitterfeld and Dessau. It was also the time just before political upheaval would descend upon East Germany. As students, we critically examined the societal reality and planning paradigm of modernism. At the same time, Weimar gave me the opportunity to undergo a study of architecture that was both oriented towards the art of building and based on engineering technology in a cosmopolitan environment. These factors ultimately led to me becoming an architect of great passion.

In addition to being Bremen’s building director, you are also part of the committee EUROPAN 17 – Living Cities. What are the greater goals of the EUROPAN initiative and what is your role as part of the committee? Who can enter the EUROPAN competition?

EUROPAN is an innovation machine for planning and building culture and an important platform for the next generation of urbanists and architects in Europe. This generation must have the chance to formulate and realise their own positions on the city of the future. As Bremen’s building director and public sector representative, I feel responsible for this. In view of the climate crisis, migration and the realities of war in the middle of Europe, as well as the social issues surrounding living and working, we need new answers for the development and design of public infrastructure in our cities, for a new mix of uses and, above all, for participation in the city and its resources. These answers must be radical and give the paradigm shift a powerful voice as well as effective imagery.

Young architects, especially in Germany, have difficulties entering selective Architecture Competitions due to a lack of built or implemented references. Why are there are so few open competitions?

Yes, this is a real dilemma – and precisely where the Europan-Competition comes in. Europan is explicitly aimed at young planners and gives them not only a stage and the international attention that comes with it, but in the best-case scenario, a first contract as well. For many a startup has been born in this way.

Overall, the dilemma has a lot to do with European law in relation to the regulations of public sector building, which is why we have to look for ways to open up to young architects and their offices or working groups. This can be successful if the awarding authorities form alliances with this as a goal. In Bremen, for example, we have developed a wild-card principle with the Chamber of Architects for the allotment of procedures, which opens up opportunities for young firms, and perhaps for inter-firm collaborations as well.

Are there other institutions that you perceived as role models or good examples? How do other public institutions influence your work? How and what did/do you learn from them?

In Bremen, I can point to an initiative by GEWOBA – that's our big municipal housing association. Every two years, it organises a student competition in cooperation with the School of Architecture in Bremen with the wonderful title: Alvar Aalto Competition. The Aalto skyscraper in Neue Vahr is a GEWOBA housing and is not only the eponym but also the programme for this special competition. In cooperation with the city, selected GEWOBA sites and properties are worked on by students.

The Bremen University of Applied Sciences works together with other schools of architecture. The competition task is offered in both Bachelor's and Master's thesis procedures. The winners of the 2020 Alvar Aalto Competition were invited by GEWOBA to take part in a competition procedure called "unusual living – children in the city" and were able to submit their designs on an "extra ticket". And they even won prizes. This is a good startup aid for graduates on the path to independence. This process taught me, among other things, that it is essential to have smart cooperation between the public sector, innovative companies and universities.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

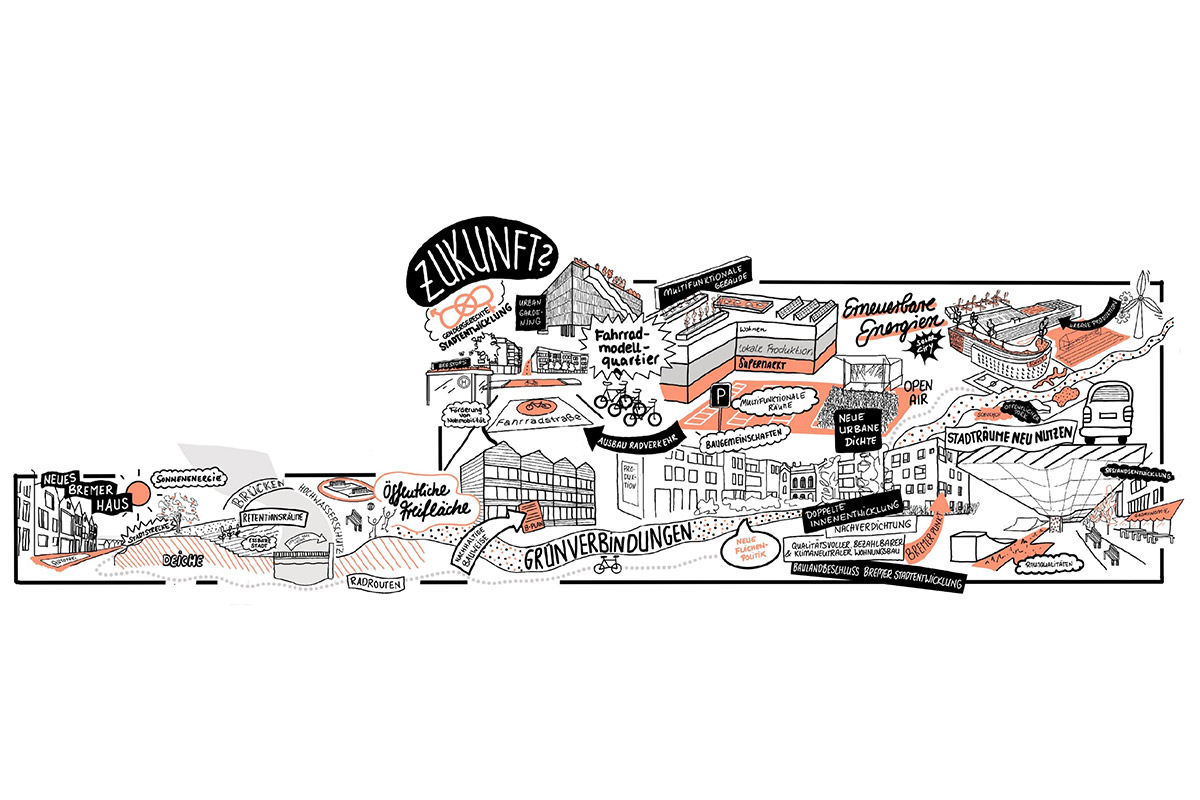

We are currently experiencing a paradigm shift. We have to switch very quickly to building within existing contexts and to a way of circular planning and building. Many projects – including those in the public sector – suddenly face the question: Is it still permissible to demolish existing buildings or must they be converted? This requires evaluation criteria and corresponding decisions from all those involved in planning, building and approving. Climate change and the requirements for CO2-neutral neighbourhoods force us to focus building on public infrastructure, energy supply, rainwater management and mobility, as well as on limiting and reducing the individual consumption of space. This leads to modified building tasks and new aesthetics. Reuse, reduction and even renunciation along with participation and sharing are linked through demanding and complex design issues. This is the modern field of architecture and the order of the day.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school, what would it be and why?

Every generation of architects has about 15 years to formulate and realise their idea for the future of cities and building. My own professional path has shown me that it is the age or, more precisely, the time between 25 and 40 that I am referring to here. Therefore, in times of upheaval, a next generation must have the courage to see, design and do things radically differently. For that, they need a chance, but they also have to seize that chance. This is only possible through positions and designs in which attitudes are expressed and become visible.

What person/collective or institution should we look into right now?

This question inspires me to tell of a recent meeting I had with a delegation of young local politicians from Odessa, in Ukraine, who were in Bremen as part of the signing of a friendship agreement on a town twinning. They reported on projects to house internally displaced persons in their city and region. In closing, they showed me their city's application for EXPO 2030. Under the exposition’s motto "What does it mean to be human?", they are searching for an answer under the guidance of their thesis statement, which reads: "The question is how technology will help us to be more human, but not to replace humanity." This is a question we in Europe must ask ourselves.

Europan

Living Cities

Europan 17

2023

Europan was founded in 1989 with the aim of promoting young architects and innovations in housing construction. In the meantime, the field of activity has broadened and the projects have become more complex. What has remained is the search for innovations and the ambition to support young teams of planners.

Every two years, a Europe-wide search is conducted for solutions under one overarching task.

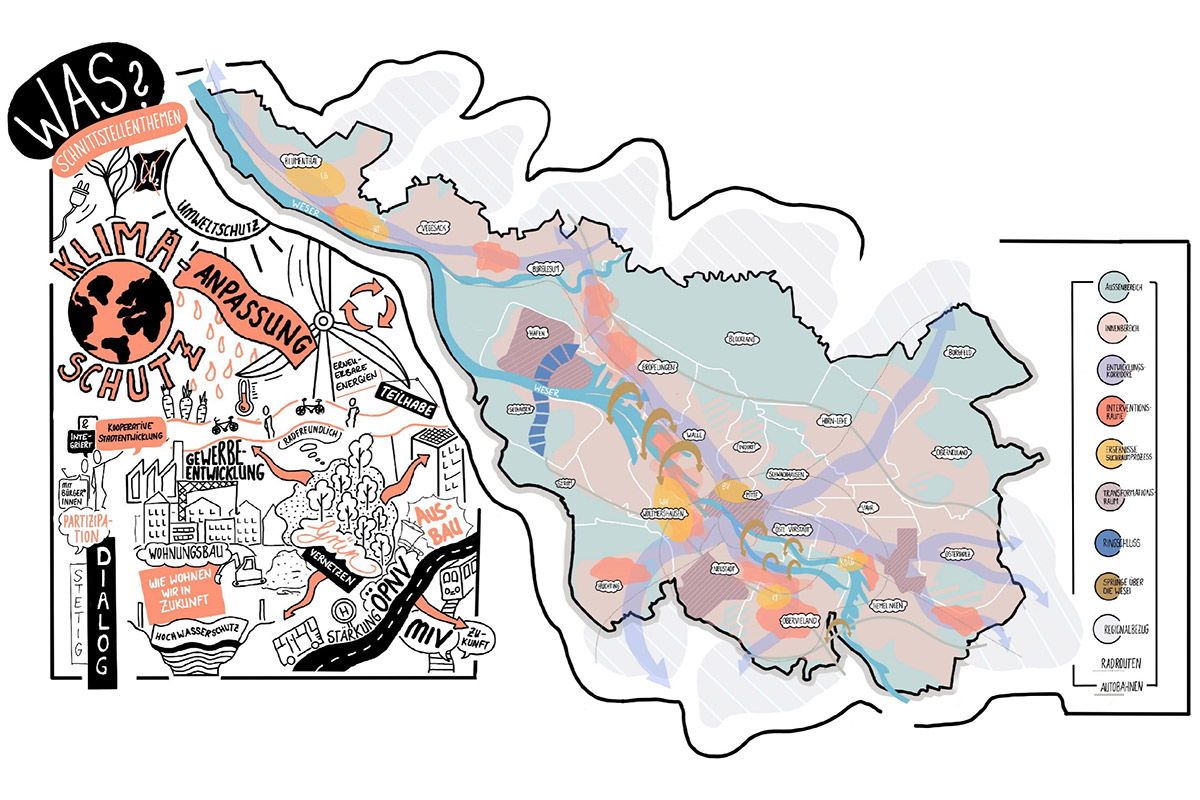

This years competition "Living Cities 2" asks how we can counter climate change and man-made social, economic and cultural inequalities in the urbanised spaces of our cities and municipalities with innovative and integrative projects and new planning processes. At more than 50 locations across Europe, promising approaches are being sought. Germany is represented with 8 sites - from the Island Borkum in the north to Munich in the south.

More information: .europan.de

Website: bauumwelt.bremen.de, europan.de

Further Reading: baunetz-campus.de

Photo Credits: © Europan © SKUMS

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 07/2023