23/006

Isabel Zintl

Architect and Mentor

«Our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us.»

«Our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us.»

«Our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us.»

«Our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us.»

«Our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us.»

Please, introduce yourself…

My name is Dr. Isabel Zintl, I am an architect and mentor and live with my family in a camper van. I studied landscape architecture and urban planning in Weihenstephan as well as architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart. Transdisciplinarity and the connection of professions and different topics and attitudes opens up my creative space.

Since graduating in 2015, I have been teaching at various universities including the TU Munich and University of Stuttgart, and I am active in research. Since 2016, thanks to scholarships from the Akademie Schloss Solitude and the Akademie der Künste Berlin, I have been able to develop a discursive way of working, i.e. creating an interdisciplinary exchange, spaces for thought and experience through workshops, design and exhibitions.

In order to create a more meaningful existence through my actions, I additionally work as an architecture mentor to help architects on their way to more awareness in their work and life. For personal development of architects I offer seminars on topics such as inner architecture. All in all, I would casually describe myself as a woman of life with a do-gooder instinct, or at least that is my drive and desire. Even more so since the birth of my daughter.

Portrait Isabel Zintl

How did you find your way into the field of (landscape) architecture?

Since I don’t have a high school diploma (Abitur in Germany), I couldn’t study at the beginning, even though I would have liked to. I am dyslexic and school was very difficult for me. At 16, I started my career by training to become a florist. It led from the individual blossom, from the direct, immediate shaping of nature to larger scales. After catching up on my school-leaving certificate, I finally studied landscape architecture, urban planning and later architecture. I felt restricted by the distinction between the professions prevalent in Central Europe and was therefore especially interested in the connection between the subjects. I wanted to become a landscape architect early on because I have a close relationship with nature, see myself as a part of it and have always enjoyed designing and creating within it. The thought makes me smile that today I have a doctorate and dyslexia... it is surprising what is possible after all.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your time at university?

I have to think of gratitude and privilege. As I never thought I would be able to study at all, I was really happy to enter this building every day. The possibilities, the thematic openness and freedom that I experienced, especially at the academy in Stuttgart, is a great gift. The foundation for my current way of thinking was laid there.

And what still comes to mind at the same time is: exclusivity. The exclusivity of studying architecture, if you take it “seriously,” superseded everything else back. Today I also see how great the pressure was, how much I worked, sometimes to the point of physical and psychological exhaustion. How unhealthy the competition was, how much focus was on performance.

According to the principle, good architecture is only created through sweat and tears. By saying this, I do not want to reproach the teachers, as this is also a general problem in our society. As long as those with the most impressive, gapless references and the most overtime are rewarded - in a society built on growth - this is naturally reflected in the universities. These patterns are exemplified by professors and teachers - as they themselves often only got into these positions through extreme performance - which has the consequence that these patterns can be internalised by students and passed on to the next generation. I think this is inhumane and questionable.

How would you characterize the place you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your work?

Since we live as a family in a camper van, our surroundings frequently change. Of course, this also has an influence on my work; in fact, I can see that my surroundings often become the starting point for my reflections. It depends, of course, on how inspiring the environment is, whether it’s a natural or an urban landscape.

Working Space

What are your thoughts on society and space?

Many women no longer have children because they take the climate predictions seriously. Women don’t have children anymore, even though they wish they would. Even in my circle of acquaintances, not just elsewhere – that leaves me speechless as a mother. THIS is so fundamental and belongs into the middle of the architectural discourse – not only because we, as part of the building sector, are responsible for about 40% of the CO2 emissions worldwide – but above all because it generally concerns our future on this earth. The small greening of facades is important but will not be enough. Exploitative growth and capital-dominated performance are no longer an option.

The profession of architecture is in a deep crisis.

Building is questionable, current teaching is questionable and architects themselves are in a crisis of purpose, as working conditions in offices are more than questionable.

Many no longer want to live and work like this in patriarchal structures under constant stress until they burn out. I know so many people to whom this has happened and who have turned away from architecture in recent years. Especially women and mothers. We need a fundamental paradigm shift.

And that goes really deep. Because this change should begin within us. To no longer make one's own value and self-image dependent on performance and work requires personal development. That is why I accompany architects as a mentor: We need these spaces.

For you personally, what is the essence of space?

Open space itself. Climatic and social changes worldwide pose enormous challenges for cities and their open spaces. Cities and their open spaces are not only reaching their spatial limits, but above all the limits of their social resilience. Already decimated by densification, existing open spaces in particular are under increasing pressure. This is due to a variety of demands being placed on the remaining areas: They provide a spatial basis for answers to pressing questions about the future. They are being built in the course of densification, and it must be remembered that, in addition to the requirements of climate change adaptation, they are open spaces that are outstanding places of social exchange. They are essential and indispensable as places of negotiation in an increasingly diverse urban society.

What needs to change in the field of landscape architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

We need a new understanding of space to meet global challenges, as the results of my research have shown. Open spaces are currently under great pressure, and it is obvious to think about the future of open spaces in general. The starting point and thesis of my doctoral thesis is a change of perspective to the vertical and the associated expansion of the otherwise mostly horizontal concept of open space. Open spaces must no longer be understood as horizontal residual spaces between buildings; this no longer does justice to their role.

The historical studies I conducted in the course of my disputation have called into question the distinction between architecture and landscape architecture, and above all between interior and exterior, which is predominant in German-speaking countries. The analyses show that the clear distinction only became possible with the use of window glass and closed building façades and is thus more recent. In many warmer climates, this distinction is often absent even today. In contrast to this, in Germany, the emphasis on the distinction between inside and outside has also been reinforced in recent years by prescribed energy-saving measures and the accompanying hermetically sealed building envelopes.

In contrast, historical observations recall that urban systems have been readable as vertical “open space systems” since time immemorial, without a climatic distinction between interior and exterior. It follows that our cities today could also be seen as climatically permeable porous structures. Against the background of global challenges, this view of space opens up a huge potential.

And please don’t get me wrong, it’s not about creating utopian elaborate vertical city structures in the distant future a la Yona Friedman or Constant, but about using this view for existing structures and providing them with different climatic layers and buffer zones, thereby creating a flowing open space in the vertical. Aspects of this understanding of space can be seen in the conversion of the “Tour Bois le Prêtre,” a post-war modernist building in Paris by the architects Lacaton & Vassal with Frédéric Druot.

By radically opening up the façade and adding a kind of winter garden, the architects create a space that is temporarily or only partially protected from the weather, an open space that probably also stores heat and reduces energy costs, according to the planning team. Designing space from the point of view of open space is already a recognised approach in urban planning and landscape architecture, but until now there has been no equivalent in the vertical, and that is precisely what we urgently need.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young landscape architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Curiosity and openness for the connection between inside and outside. By that I don’t just mean the transition between architecture and landscape architecture and the corresponding spaces in between, but I think it’s important to learn to recognize that global processes manifest themselves locally and that there is always a connection between the inner life of people and our built environment.

After all, our future is not first created on the plan, but primarily within us. That’s why I’m increasingly interested in architects themselves as a starting point. This is where opportunities for sustainable change can be found, which is why I started working as a mentor. For a long time, I have wondered where this numbness actually comes from, the inactivity and inertia in the face of crushing climatic forecasts and the challenges that lie ahead. This form of numbness can also be interpreted as a symptom of epigenetic trauma inheritance. It has been researched, for example, that traumas and fears such as those of the Second World War are passed on for up to six generations.

Of course, this is first of all a collective social and personal issue, but I think it is important to be aware of this, especially as an architect or landscape architect. Because if left unprocessed, trauma and fears have an unconscious effect in us, in our creating and designing – otherwise they are cast in concrete and continue to have an effect there.

Whom would you call your mentor?

Prof. Dr. Ferdinand Ludwig, professor at the TU Munich and representative of baubotanik, he is my doctoral supervisor and has accompanied me intensively over the past years.

Prof. Dr. Martina Baum – as head of the Urban Design Institute at the University of Stuttgart, much of what I know today and my attitude towards cities was shaped by her and my colleagues at the time. I also remember a very important moment for me, when I was still a little student assistant at the chair: she entered the chair for the first time, pregnant with a baby bump. Since then I know: everything is possible.

Guido Hager, a truly wonderful landscape architect who has accompanied me from the beginning of my journey, his innovative and at the same time preserving view of space has left a lasting impression on me.

Prof. Regine Keller as second examiner of my doctoral thesis. She and her chair are a universe in themselves and for me, her view of landscape architecture is very inspiring.

Jeanne de Kroon – without knowing her personally – is not an architect, but thanks to her I believe that everything can be interwoven, and nothing should be excluded. That it is possible to live your feminine side as a woman, that another form of success is possible. Sustainable, colorful and nurturing.

Name your favorite …

Book: Freiraum vertikal denken

Person: My daughter Lola

Open Space: The sea

Building: SESC Pompéia by Lina Bo Bardi

Which material fascinates you (at the moment)?

Always: earth, topsoil, loam and clay as the basis of our life. Working with clay, and I don't mean making vases, but really getting involved with the material, was a crossroads for me and my research at the TU Munich. It made me remember, amidst all the stuffiness at university, what we really are: a part of nature. It seems to me that we sometimes forget that. And if you ask this question to a landscape architect, of course it’s plants: I especially love columbines, fig trees, sweet chestnuts, larches and many other plants.

How do you communicate/present your work?

Themes that keep me busy find their place in courses and workshops, exhibitions such as for the Akademie der Künste Berlin and in publications. This always results from the context in which I work – in 2023 my next major stop will be as a scholarship holder for the German Study Centre in Venice. I am curious to see what kind of working method will unfold from living and working on the Grand Canal ;)

How did the coronavirus change the way you work?

The pandemic has set me free. Of course, the situation was not easy for me and my family at first... but I think it is so important to recognise the opportunity in difficult situations. Due to the containing changes caused by Covid, I have become much freer in my way of thinking and creating. Thanks to Covid I dared to follow a deep desire and move into a camper two years ago, at that time with my baby. Location-independent income was a much more difficult rather extraordinary topic before the pandemic, which has become much easier with all the online formats. Living in a camper as a scientist? Why not?

What person/collective or project do we need to look into?

In this context, I would like to recommend the film "Bodenlos" by landscape architect Prof. Regine Keller and Munich’s former city planning councillor Christiane Thalgott: “Living soil is the key to human viability”. I think this film is so valuable because it tells us that we have to remember our roots in order not to become “bottomless”. The way we treat our topsoil is a symbol of how we treat our earth, how we compact it and deprive it of life and with it the basis of our existence.

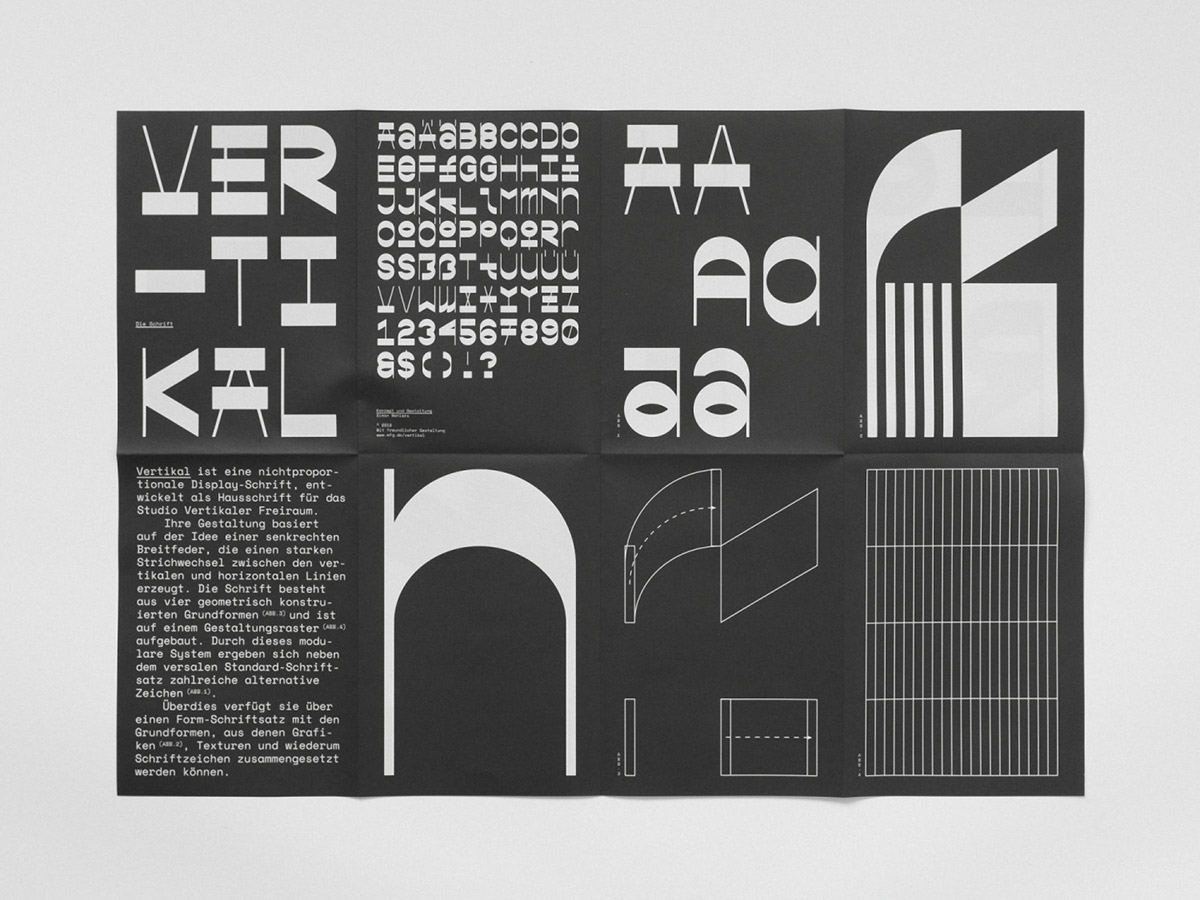

Project 1

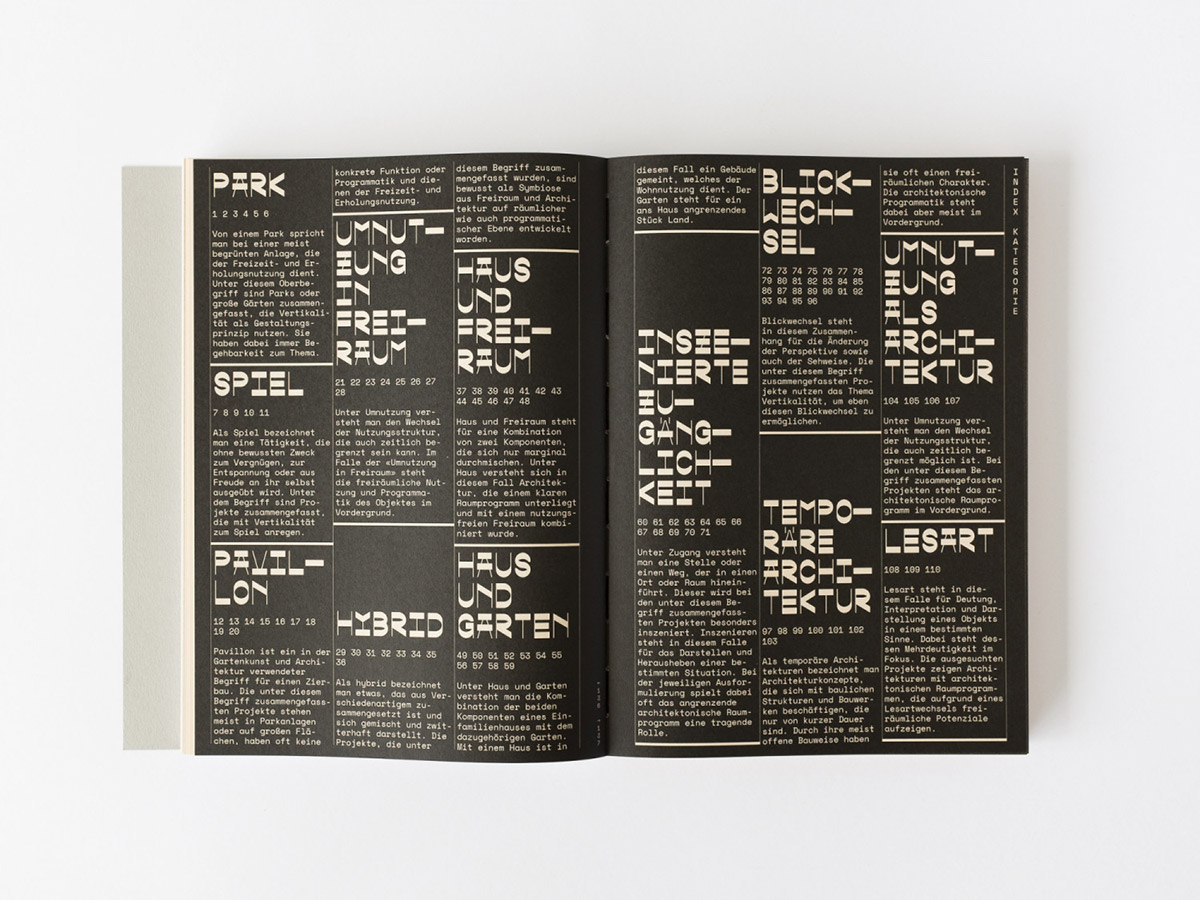

Freiraum Vertikal denken

Thinking about verticality – is a change of perspective upwards – expands the space and frees it for new perspectives. This change also enables a new way of thinking about the future of urban open spaces. For when previously horizontal open spaces are expanded into the vertical, new and inspiring perspectives open up. In view of the pressing social and climatic challenges worldwide, these new approaches are more necessary than ever: new answers must be found that will make it possible to live well together in the city of the future.

With contributions by Mirko Borsche, Kees Christiaanse, Eugen Gomringer, Herman Hertzberger, Fons Hickmann, Eike König, Erik Spiekermann and many more.

Editors: Isabel Zintl, Simon Wahlers, Ferdinand Ludwig

Publishers: Technische Universität München, Fakultät für Architektur

ISBN: 978-3-941370-91-3

Format: 17 × 24 cm, 408 pages

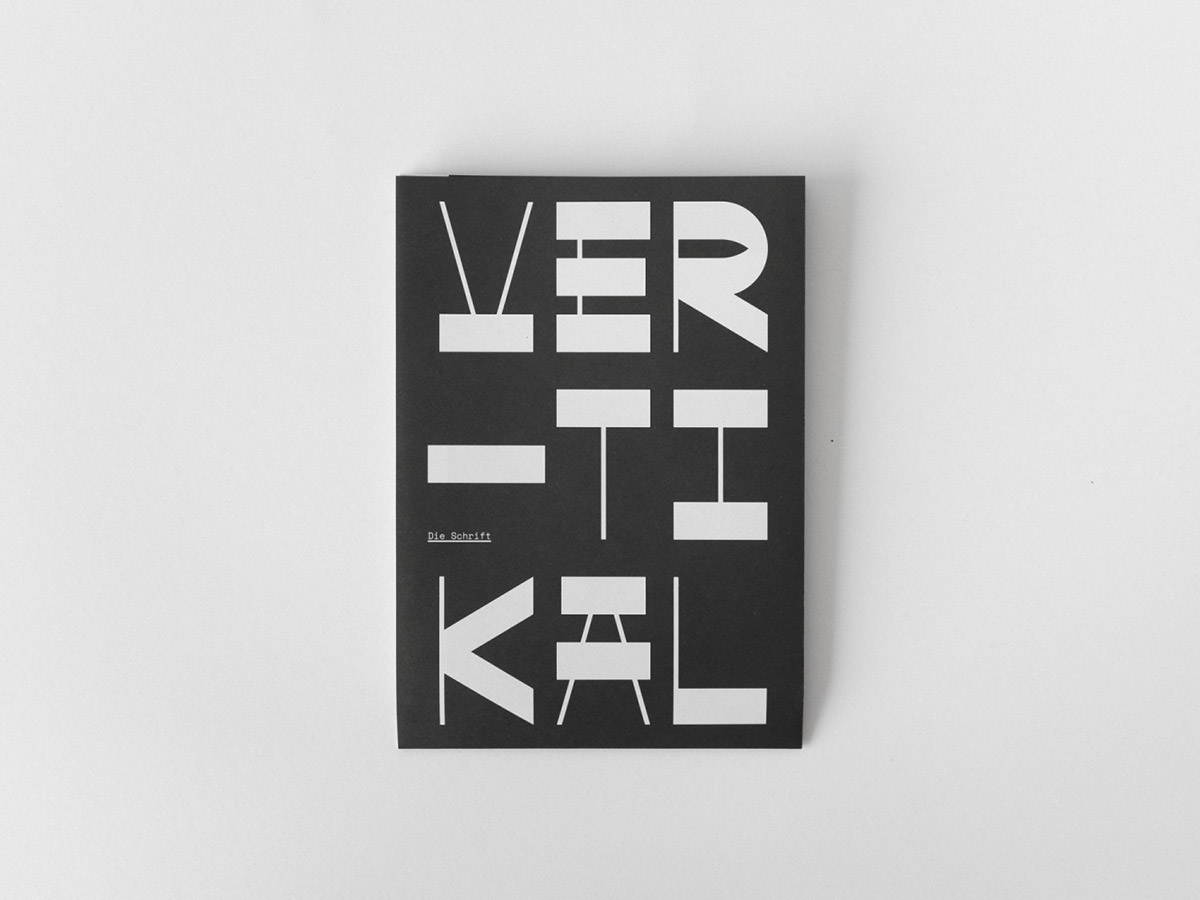

Project 2

Komm in die Vertikale

“Komm in die Vertikale” is a touring exhibition that explains the topic of vertical open spaces in the context of landscape architecture, architecture and urban planning and makes it possible to experience them.

The exhibition was shown in the cities of Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, and Stuttgart. While the theme remains the same, it is designed to respond individually to the environment in which it is shown. Through this specific orientation, the content can be experienced intuitively by the visitor. For vertical open spaces can be found everywhere. The visitor is invited to sharpen their gaze and change their perspective.

Website: vertikalerfreiraum.de

Instagram: @isabelzintl

Photo Credits: © Isabel Zintl, © Frédéric Henry, © Simon Wahlers

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 04/2023