21/025

Jonathan Burlow

Architect

Folkestone

«The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong.»

«The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong.»

«The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong.»

«The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong.»

«The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

My name is Jonathan Burlow and I’m a British-French architect based out of Folkestone, United Kingdom. After several years of collaboration with various well-established practices, I founded my own studio - Jonathan Burlow Architects - in 2018 with the ambition of developing highly specific, collaborative projects. I was born in Bangkok, and grew up in Laos and Pakistan, instilling from an early age a deep curiosity and passion to enhance and celebrate the diverse environments and cultures found in human societies through our work.

The studio’s work has gained recognition through several awards, such as the 2021 Build Magazine Award for ‘Most Innovative Residential Architect’, with further distinctions including ‘Over the Edge’ being selected as ‘The Best of 2020’ by Archello and the practice being featured in the Architecture Foundation’s ‘New Architects 4’, a major publication surveying the best British architecture firms established in the past 10 years.

Portrait Jonathan Burlow

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

Mostly by chance! From a very young age, I have always been obsessed with drawing anything from my imagination (this very much remains the case today). As I continued to grow, I was fascinated by many subjects and architecture presented itself as a field that allowed me to incorporate all aspects of my interests into one focus.

What are your experiences founding your own studio?

I started the studio mostly subconsciously. It was more intuitive than a calculated decision. The driving force was the creative freedom - the ability to develop my own thinking and approach to architecture. It was a conscious rejection of accepting the dogma of someone else’s ‘style’ or thinking. I was fortunate to be approached by our first client back in 2018 for a small extension, now titled ‘Over the Edge’. The project evolved into really a ‘love affair’ (as are all the projects we take on), which resulted in many positive write-ups in the likes of Architectural Digest, Dezeen, Archdaily, Wallpaper magazine, etc. This helped to bring attention and new work, albeit through the mist of a global pandemic.

As the studio is carefully growing it is rewarding to see our projects gradually getting larger, bringing different challenges with them. However, we are interested in how we can continue to approach them with the same rigor, depth and intensity. We aim to always push our projects to invent and maximise all opportunities present.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

I was born in Bangkok and spent my childhood growing up in Laos and Pakistan due to my father’s career as a hydro engineer, eventually settling and starting my secondary education in Folkestone. Architecture has taken me across the UK, studying in Portsmouth, Bath and London, however, establishing a studio outside of a city, by the sea in Folkestone, felt like a breath of fresh air.

Folkestone is a little coastal town in Kent, UK, just an arm’s reach across the Channel from France. Today, the town is becoming a hub for both local and international culture, most famously as the home of the ‘Folkestone Triennial’ - a growing event that turns the town into an outdoor art museum throughout the summer, featuring permanent sculptures by international artists such as Antony Gormley.

But going back some time to around the 18thcentury, Folkestone was a quiet seaside town with a thriving commercial port for fishing and ferry services to and from Boulogne. Later, in 1844, the construction of the ‘Harbour Arm’ took place out into deeper water to allow for larger ships to dock at any stage of the tide, allowing the town to play a key role throughout the First World War. It also enabled the rail line to be extended to reach the ferries; this investment in transport infrastructure had the advantage of enabling the Orient Express direct access between London’s Victoria Station and Folkestone Harbour, and passengers were able to embark and disembark near the cross-channel ferries moored alongside the Harbour Arm. Thus, the world’s first ocean-going ‘boat train’ was established, strengthening Folkestone’s reputation as the primary connection with Continental Europe.

With the town’s historical role in connecting the UK with Europe and the wider world, practicing architecture here has felt much larger contextually even though it may be seen as a ‘small seaside town’. The area certainly has a deep embodiment of a ‘working harbour’ with the presence of a global connection! The drive for our work to connect far beyond the local context is strong. However, in parallel, we aim to contribute to the local development and cultural growth of the town in the immediate future.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Whom would you call your mentor?

I don’t have a traditional ‘mentor’ - my pantheon is full of very different people who inspire and influence my thinking continuously! I do not necessarily agree with the traditional idea of having a mentor in the creative field as this often produces offspring subconsciously trapped by the notion of dogma. For these reasons are why I rejected the norm of working in a practice for any sustained period prior to establishing my own studio.

Name your favorite …

Collaboration: Quincy Jones/ Frank Sinatra

A space you wish to visit: Marble Caves, Patagonia

How do you communicate/present Architecture?

We present our work in many ways; we do not necessarily believe in one fixed ‘style’ of presentation as each project is perceived by many different audiences, through many mediums of physical reality, as well as all the different digital outlets. For a client, work is presented through a process of evolving the idea first verbally, then expressing a dialogue into a sketch to enhance a further conversation, through to conceptual models and scale drawings, until hopefully the final, constructed reality of the idea. However, for most of our audience, they will only ever be presented with our work digitally, therefore a moment in time is only ever the reality of a photograph, sketch or model.

How has COVID-19 changed the way you work?

I founded the practice towards the end of 2018, so in a way I really don’t know a world working in a normal economical context. I can only take this as an early advantage, and if we are able to grow and develop meaningful work in a global downturn like this, it only makes me more positive and focused to develop larger, more culturally meaningful projects in the future

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

I believe school is great for helping to develop a set of basic or essential skills, almost like a toolbox. You can have the tools to carry out different tasks but what is important is to collect a wide set of tools to be able to apply them to any future situation. In practice, you will most likely become skilled and develop more depth using only a few certain tools, so during your studies it’s important to test and try out all different aspects of the craft (digital, physical, theoretical, etc). This will help you to find what skillset really brings you joy, and then try to find a role in your craft (being stuck at the computer is not fun when you enjoy model making, but you must taste all to find what you like first).

Project 1

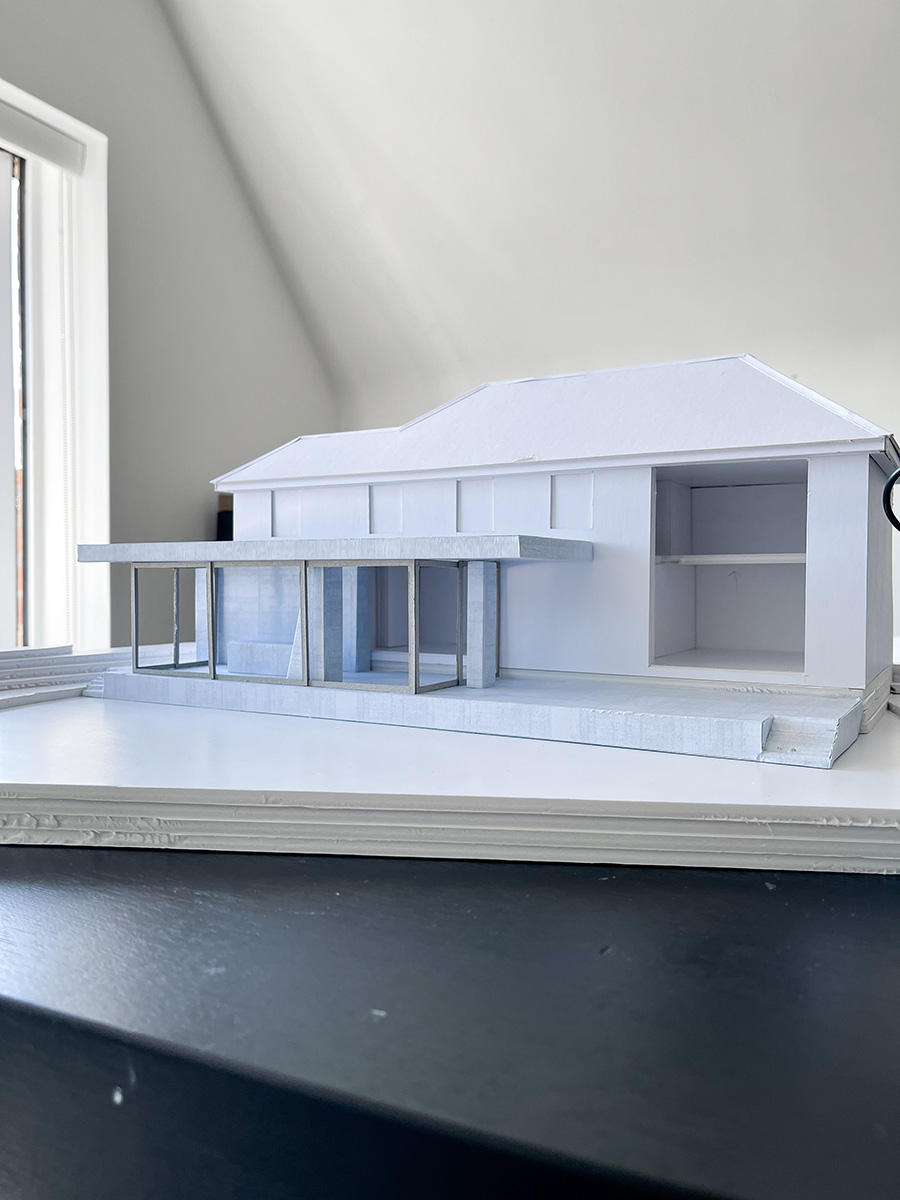

Over the Edge

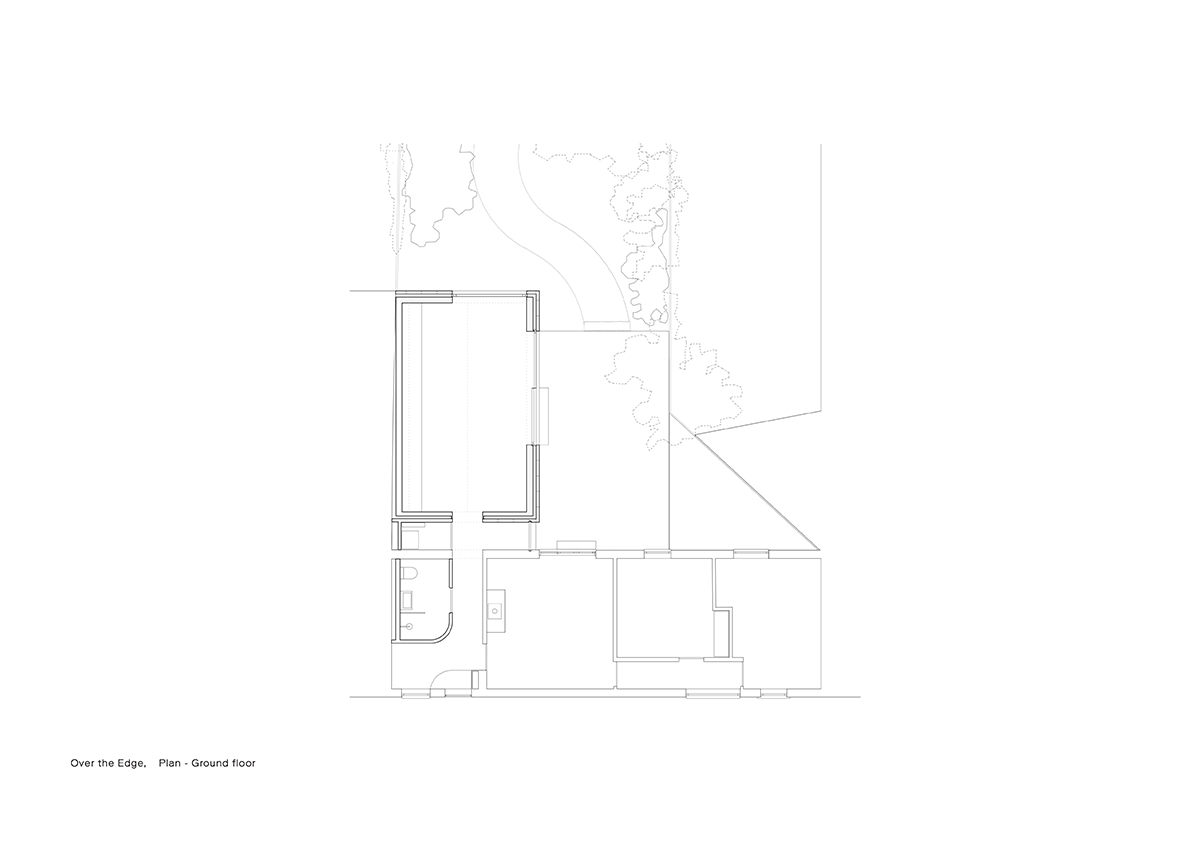

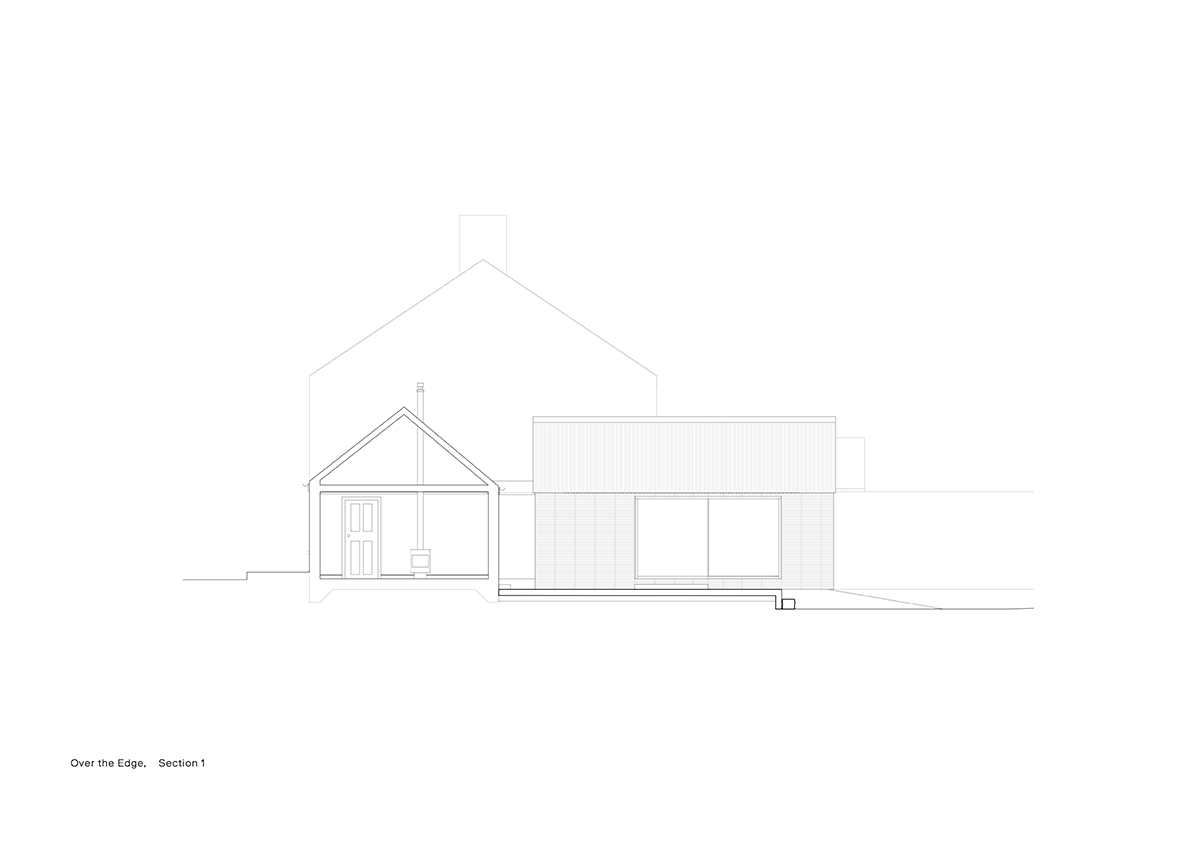

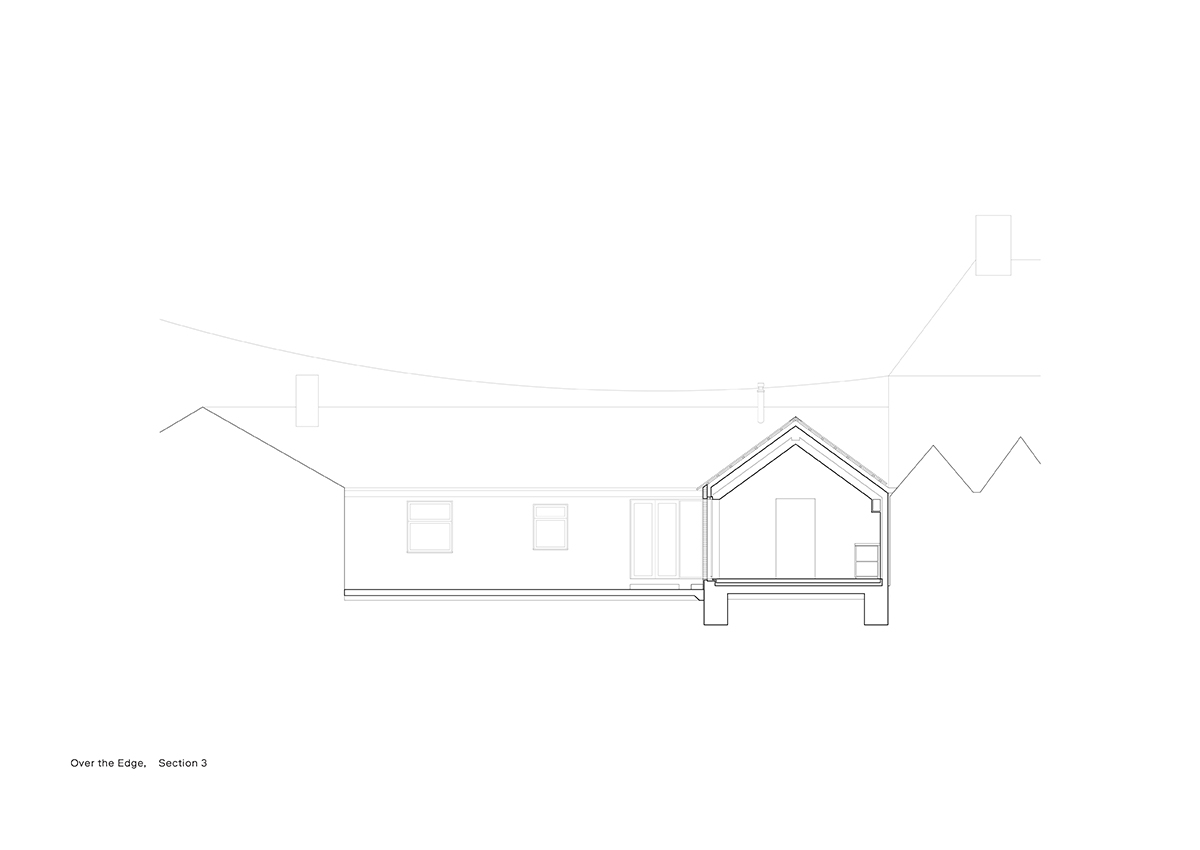

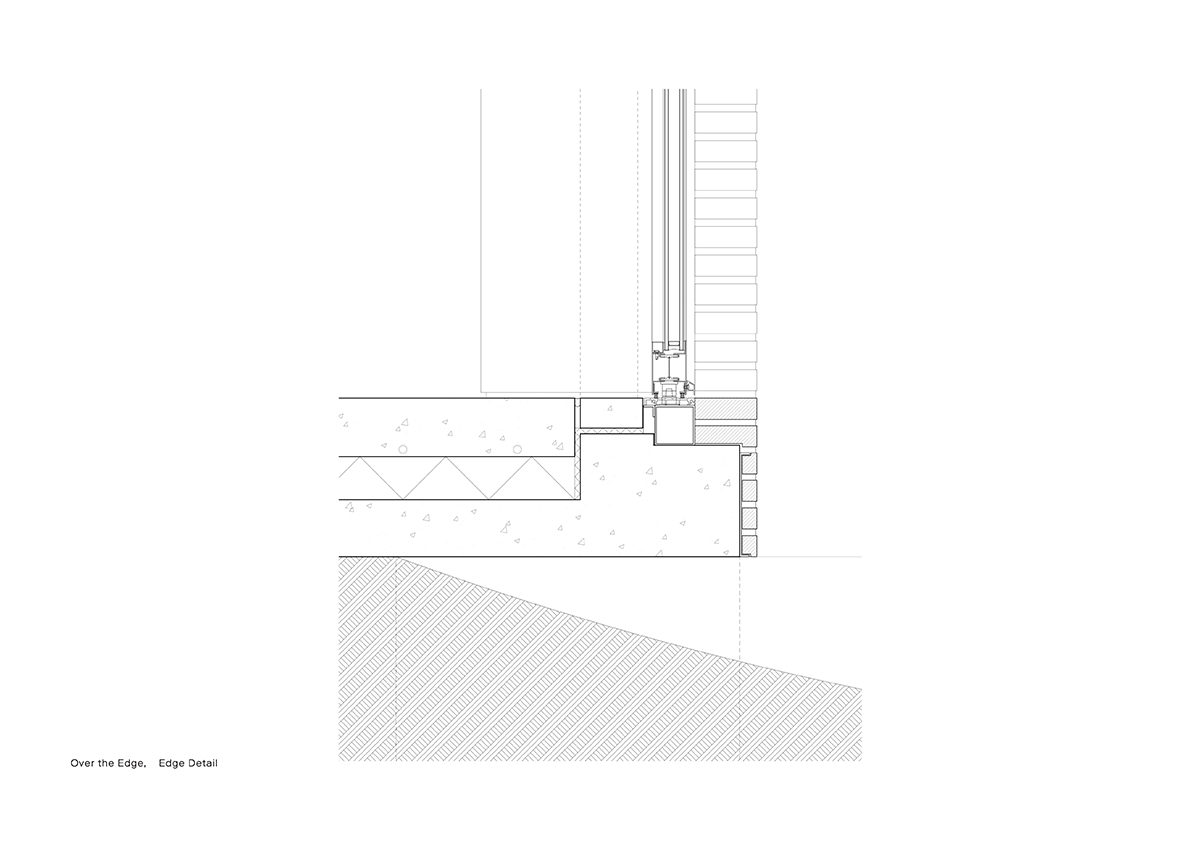

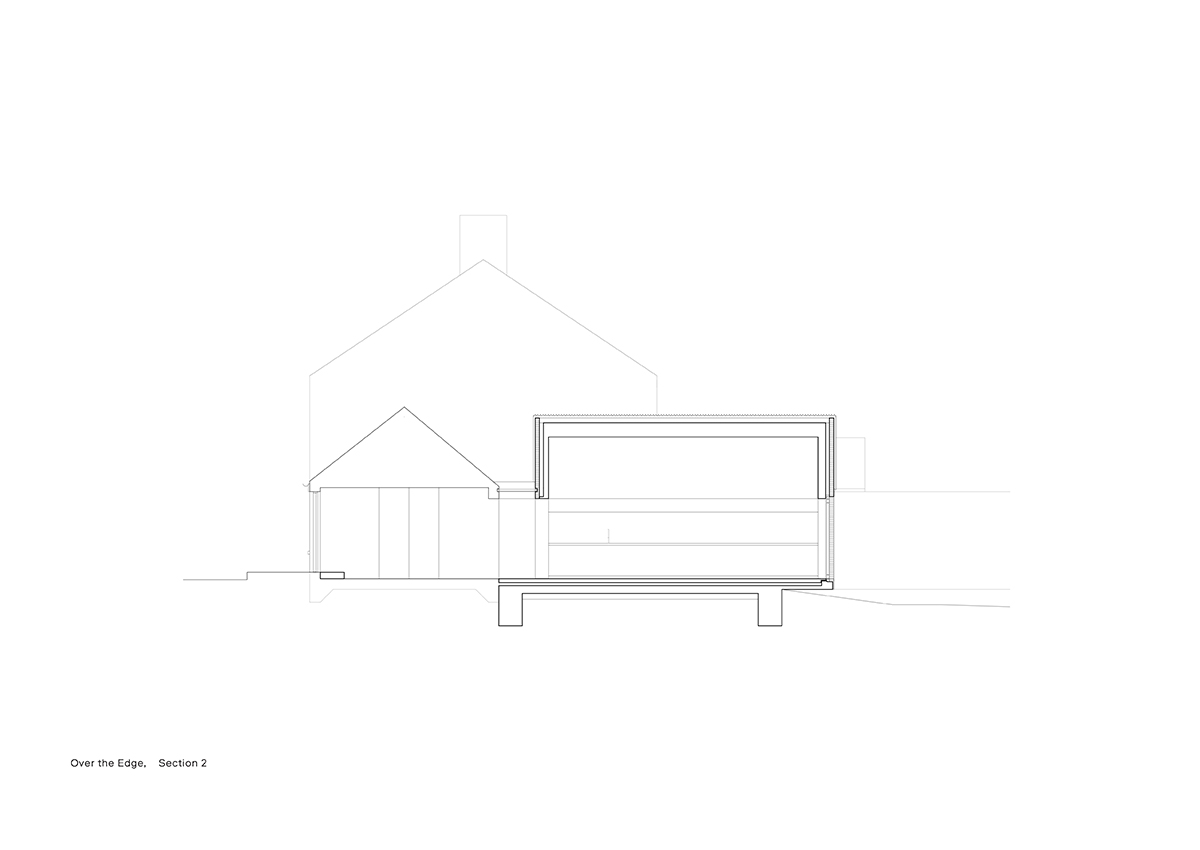

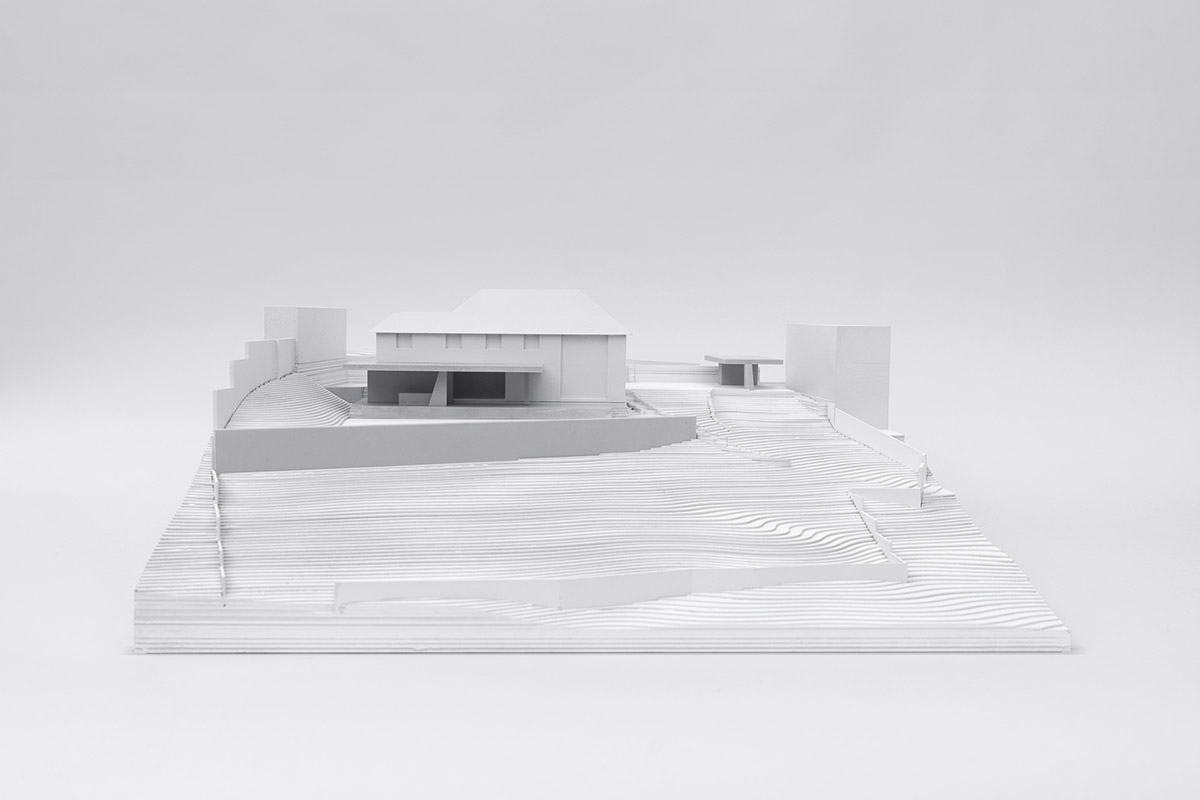

Over the Edge is an extension/transformation of an old grain store building with origins dating back to the mid-19th century. The project is set in a confined context, with the architecture aiming to exploit the potential of the site in a furtive manner. The extension takes on a superficial configuration of the existing house’s prototypical elements - large windows, brick walls and a pitched roof. In doing so, the addition is aligned within its context yet pronouncing itself through a refinement of substance.

The concept of the addition to the main house arrives as an expression of the ideologies behind the historic rural grain store buildings typically constructed in southern England during the 18th century. Commonly, grain store buildings were built separated from the main house on saddle stones, lifting the granaries above the ground, thereby protecting the stored grain from vermin and water seepage. The extension references the rationale at the time, lifting the kitchen from the ground and placing the space on a concrete pedestal.

In giving the appearance of separation, the addition is pushed away from the main house, causing the extension to project over the edge of the concrete. The landscape falls away beneath the cantilevered edge, giving the impression of being lifted from the ground.

Photography → Simone Bossi

Built Space

Model

Drawings

Project 2

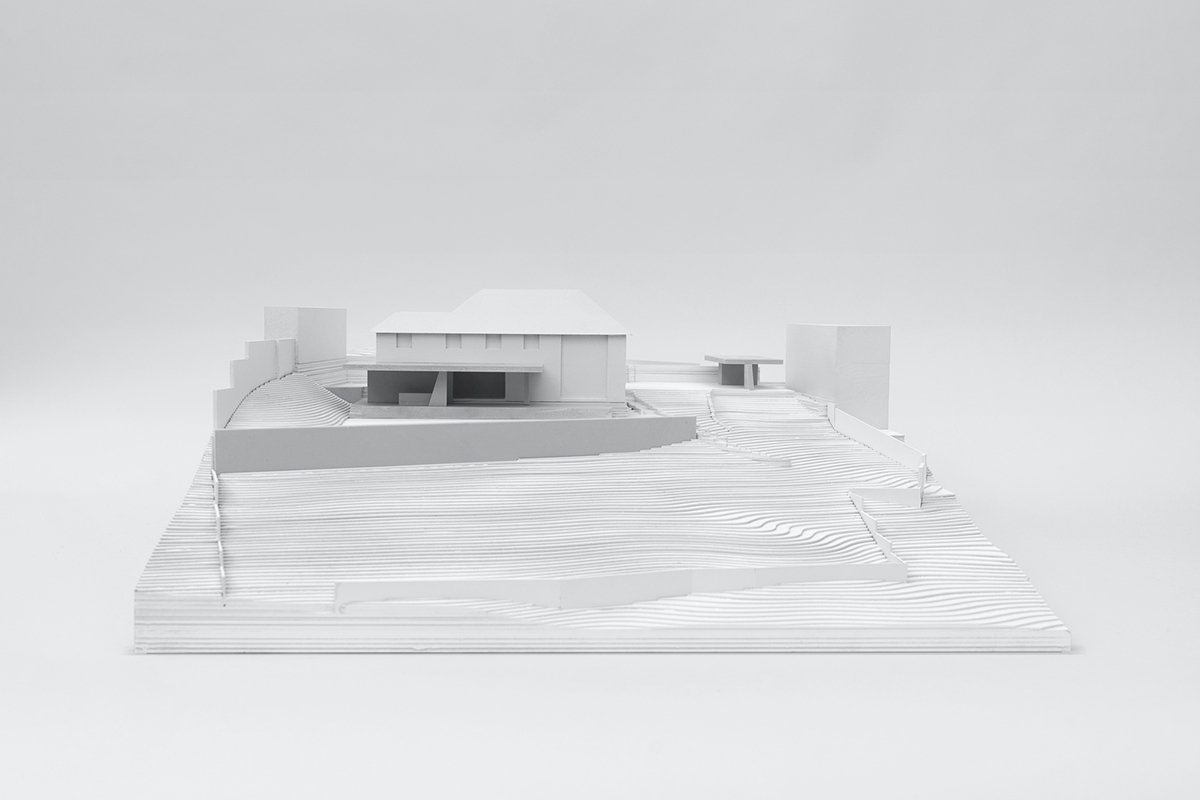

Pavilion House

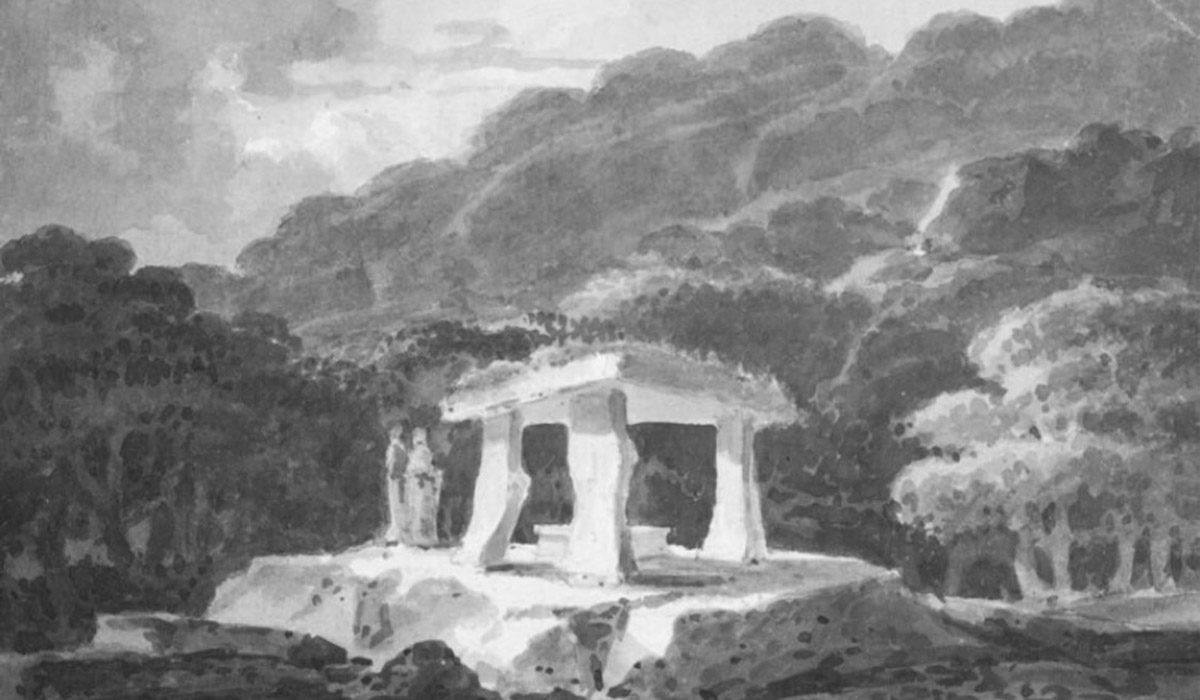

Pavilion House is an extension/transformation of a Victorian/Edwardian replica house, built in 1983. The primary gesture at the core of the project is the concept of expressing very archaic impulses; to strip the architecture down to its purest form in respect of remaining subservient to the immediate context.

The proposed extension replaces an existing, poorly constructed ‘sunroom’ at the rear of the property. The architecture of the new additions results from everything integrated into one thing (structure = space = ornament), while at the same time aiming to convey an element of time behind its thinking. The quality and condition may eventually fade, but the spirituality of the project and space will remain long after its original function – hopefully standing the test of time.

Taking advantage of the slope towards the sea and the views of the English Channel, the project defines a single elongated volume, inserted in the challenging terrain following the existing terracing. It is a podium with a large overhanging roof supported only by large concrete pillars – positioned primarily in accordance with structural requirements. The podium defines a new relationship between the house, the slope and the sea. Between the concrete structure, one simple glazed volume completely opens to the seemingly infinite coastal landscape.

Pavillon House

Website: www.jonathanburlow.co.uk

Instagram: @jonathanburlowarchitects

Facebook: @jonathanburlowarchitects

Photo Credits: © Jonathan Burlow, © Simone Bossi

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 09/2021