21/018

Khensani de Klerk

Architectural Designer

Johannesburg/Cambridge

«I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.»

«I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.»

«I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.»

«I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.»

«I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.»

Please, introduce yourself…

I am an architectural designer and planner from Johannesburg. My efforts are centred practicing intersectionality in the architectural industry through research and practice. I am also the founder and co-director of Matri-Archi(tecture) which is a collective that empowers African women as a network dedicated to African spatial education and development. I am currently concluding an MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (RIBA II) at the University of Cambridge focusing on safe space, infrastructure and social provision with aims to reduce Gender-based violence in cities, namely Cape Town. This research is situated between South Africa and Switzerland and is conceptually located at the intersection of architecture, social science and public policy. Within spatial practice, I consider myself a multidisciplinary artist, finding a language in spatial, written and auditory explorations. I host a podcast called KONTEXT which invites different voices to discuss place-centred research methods and also uses spoken word in other projects to foreground storytelling as critical to spatial knowledge production. I am also an occasional editorial contributor at The Architectural Review in London.

Khensani de Klerk © Charles Hui of Viswerk

Khensani de Klerk © Charles Hui of Viswerk

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and later the extended field of architecture you are working in now?

My context influenced me deeply and I suppose this is the main reason I place an importance on always departing from both the tangible and intangible aspects of the built environment in my research methodologies. As a Black South African ‘born-free’¹ woman, I had to make a decision to pursue a sustainable career which is socially often recognised as a professional path. I may have been an artist otherwise, but I am grateful to have been interested in technicality and form from a young age. As a result, I pursued architectural studies at the University of Cape Town (UCT). My initial ingress to architecture was again deeply affected by the context of the RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall protests that called for a decolonial and African empowering education, and consequently developed my character and critical outlook particularly concerning the political and social implications of space. Many of the questions that mould my perspective were developed during this time. Since, I constantly ask myself who designs space? What are the histories of this space? Who lays claim to this space?

¹ born free refers to born post-Apartheid in South Africa

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and later the extended field of architecture you are working in now?

My context influenced me deeply and I suppose this is the main reason I place an importance on always departing from both the tangible and intangible aspects of the built environment in my research methodologies. As a Black South African ‘born-free’¹ woman, I had to make a decision to pursue a sustainable career which is socially often recognised as a professional path. I may have been an artist otherwise, but I am grateful to have been interested in technicality and form from a young age. As a result, I pursued architectural studies at the University of Cape Town (UCT). My initial ingress to architecture was again deeply affected by the context of the RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall protests that called for a decolonial and African empowering education, and consequently developed my character and critical outlook particularly concerning the political and social implications of space. Many of the questions that mould my perspective were developed during this time. Since, I constantly ask myself who designs space? What are the histories of this space? Who lays claim to this space?

¹ born free refers to born post-Apartheid in South Africa

During my time at UCT I grew curious about the legislative, policy and economic factors that influence and often determine the scope of architectural intervention. Consequently, I then pursued a second degree in City Planning at UCT. I believe this was by no means a diversion from architecture, but rather brought me closer to understanding the realities of architectural agency at various scales.

I mention my positionality as a Black South African woman because my experience of South African cities – Cape Town and Johannesburg – was largely determined by routines focused on safety as a mode of survival. I found that these tactics around mobility, occupation and navigation that many citizens develop and employ were not considered critically in methodologies, mapping and curricula at the time. Parallel to this degree, I spent a year as a mobility student at the Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at the ETH Zürich where we focused on participative methods in informal settlements for a housing project in Cape Town. This distance from South Africa was a privilege that afforded me the opportunity to reflect and learn about other urban environments that fostered a safe space for me to actively think and be creative without being implicated by the compounded issues I faced in South Africa. I think one can do meaningful work across multiple geographies, collaborating and sustaining initiatives with care as a point of departure. I found others who thought alike and initiated Matri-Archi, which grew into a collective.

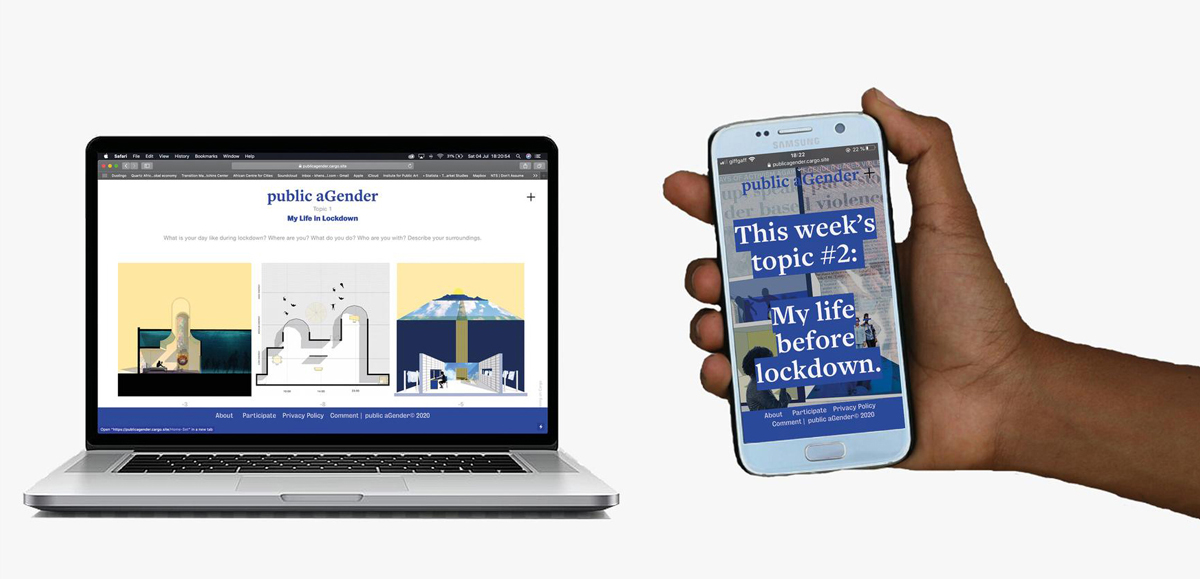

I co-direct this with Swiss-Nigerian architect Solange Mbanefo. It became more and more evident to me, that including, recognising and involving diverse perspectives of the built environment is central to practicing intersectionality. This, coupled with a curiosity and desire to traverse multiple scales, informed my decision to study at the University of Cambridge where the MPhil programme in Architecture and Urban Design focuses specifically on context, nuanced research and method. My current work is titled public aGender, which has developed into a digital platform for visually storytelling issues, ideas and imaginations by survivors of Gender-based violence in Cape Town.

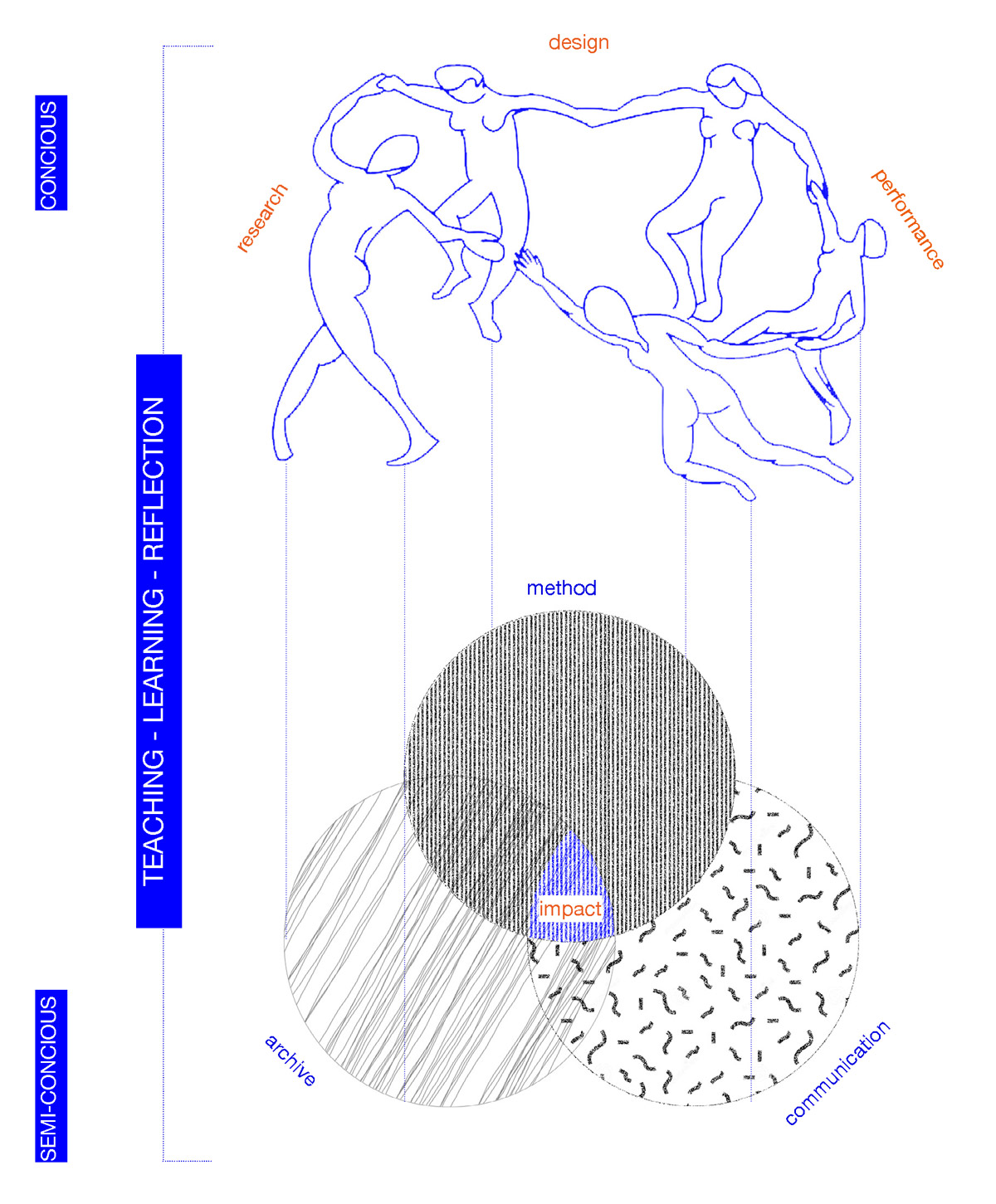

I have also been conducting research about typologies of safe space, mainly on shelters for the abused which has also relied extensively on the Frauenhäuser in Switzerland as a central case study. I am set to complete the MPhil this 2021 summer. My focus is rooted in method, communication, archive and impact. Undoubtedly, culture and language affect this, and questioning what role space and the visual world have to play in that continues to define my professional trajectory in research, policy and design.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your Masters project?

I see method as practice, and practice as a developing method. My MPhil project has allowed me to explore this by engaging in an endless space of opportunity that lies in the assumed binary between academia and ‘real life’. Simply, my MPhil project has allowed me to develop an approach that I hope to grow beyond the degree which is a method focusing on communicating critical development considerations across practitioners and those members of society who can affect change by using architecture and design as a medium for communication. I often refer to my method as a conduit and a vessel. It is a conduit in communicating unimagined futures, reflecting everyday life and telling untold or overlooked histories. It is a vessel in archiving the aforementioned in a visual and accessible format. I conceptualised this method through public aGender. The guidance of my supervisors Dr Nick Simcik Arese (Cambridge University) and Dr Francesca Sobande (Cardiff University) moulded my approach, constantly challenging the methodology to imagine alternative field work approaches, prioritise ethics and recognise the long-term life of the work we collectively create.

public aGender

public aGender

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing and thinking about architecture?

Location is an interesting contestation in a pandemic world. Luckily I have always seen the digital space as a credible location for existing and engaging as much as I value physical interaction. I am currently based in Cambridge which is largely owned by the university. The buildings in their prestigious well-kept appearances are also consequently owned by the university in a collegiate system which limits access to various aspects of the town. In pre-pandemic times, this was not too noticeable as buildings allowed for public access, and access to their reserved river banks. Since the pandemic, the situation has become antipodal, with public access limited to the facades of Cambridge building. Simply, my context has tested my imagination more than I could have expected, begging me to engage with peripheries, creeks and areas outside of the footprints of university-owned buildings that make up majority of the Cambridge town centre. Although I am based in Cambridge, I have however also spent a significant amount of time parallel in Zürich conducting case study work on safe space and public (social) infrastructural provision. The urban configurations between park, playground, kindergarten and residential forms continue to inspire and inform my urban approach to how one might imagine safety and care mechanisms on the ground.

Experiencing context is often critical to understanding social codes, space and rituals. My experience of both Cambridge and Zürich in this regard has brought to the fore aspects of mobility that largely increase and affect the safety of space for women in urban contexts. In this sense, these cities have allowed me to experience and understand possibilities of safety, whilst valuing the years of experience and familiarity I have with my site of research in Cape Town.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Thoughts, scribe, spier, Cambridge, 2021

Thoughts, scribe, spier, Cambridge, 2021

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

For me this is a constellation of different conscious and semi-conscious actions happening all the time. Those semi-conscious actions happen regardless of the architect’s presence but I believe are understood in architectural lexicons as method, communication, archive and impact. And then there are the conscious actions which for me, can be made legible through design, research and performance. I strive to do this through my own work. These actions exist in a constellation and dance with one another, presenting a different understanding outside of the fixed categories, we’ve relied on and been taught in canonical schools of thought. These conscious and unconscious actions are constantly intersecting and malleable to contextual changes.

the essence of architecture

the essence of architecture

Name your favorite …

Text: Black Vernacular: Cultural Practice as Architecture by bell hooks; an essay in her book Art on my Mind (1995.

Building: I have two different favourites for two different reasons:

Kariakoo Market (1974)in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania designed by Beda J Amuli. Why? Its announcing scale yet ability to host multiple happenings under and beyond its grand sheltered roof makes me think of (im)permanence, landmarks, belonging and dignity. Despite not being used optimally today, its design is an incredible approach to sustainable rain water collection, and from my experience of it, is significantly effective with ventilation and temperature control hosting Dar es Salaam’s biggest fresh produce market.

Im Birch School (2004)in Zürich, Switzerland designed by Peter Märkli. Why? It exemplifies a generosity of spirit, giving multiple and diverse users a sense of belonging through user-based ownership. The playground overlays with a public circulation corridor and the park serves as an extended playground. I used to walk there everyday, and admired witnessing various negotiations (between business people, children, the elderly, teenagers etc) of how the space is used, looked over and collectively cared for.

You are co-director of Matri-Archi(tecture), an intersectional collective that empowers African women as a network dedicated to African built development and spatial education. How does this influence the way you communicate architecture? Why did you decide to use this specific way of creating a collective to communicating/presenting architecture?

I believe that Matri-Archi(tecture) and the current proliferation of many other meaningful collectives in architecture are a creative response to creating spaces (networks and collaborations) where emerging thinkers can co-create, which I believe is largely a result of the inability of institutions and corporations to work towards transformation. Hinderances such as slow-changing policies and gatekeeping commissions are a few examples of how organisations not only protect privileges and favour specific histories, but also how they do not allow for the change that an ever-diversifying world begs for. For this reason, I don’t see Matri-Archi as radical, but rather an alternative space for maintaining creative momentum and collectively prototyping ideas in research and design across mediums that are possible and perhaps more fitting for the subject concerned. My initial intentions when creating Matri-Archi were to create a space where we can collectively share those overlooked, unpublicised and largely inaccessible spatial aspects that influence our lives so heavily but that we don’t see so often in traditional education and spatial production. Being affected by and affecting the built environment is certainly a du Boisian double consciousness, as WEB du Bois writes in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) which I hope, through collectives, we can subvert and use as a proactive way to respond to the challenges and needs that architecture can make a difference in.

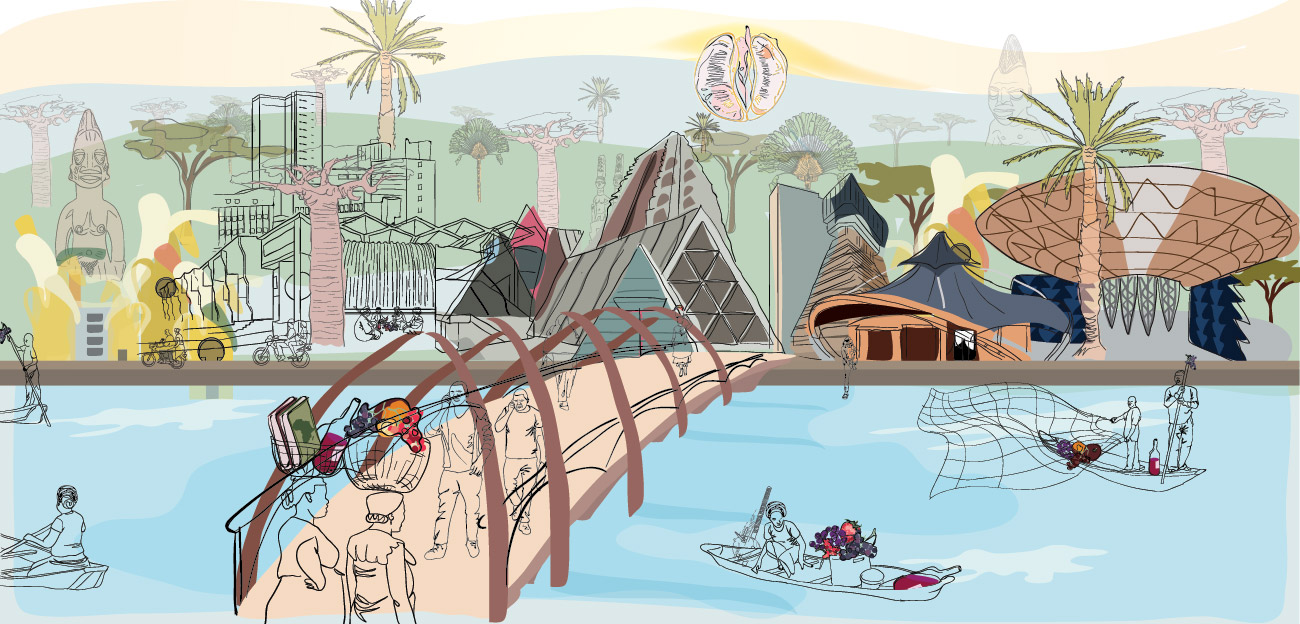

Matri-Archi(tecture), the Imagined City

Matri-Archi(tecture), the Imagined City

Matri-Archi constantly affects my thinking in viewing architecture as a discipline in relationship with other disciplines presenting exciting teachings and lessons in methods of production. Matri-Archi is a pluri-disciplinary team with members in filmmaking, graphic design, urbanism, law, sociology and architecture. This mixed space has personally taught me to constantly improve my modes of communication from having to share and make legible ideas beyond traditional architecture which has remained an elite and siloed discipline.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future? What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

If we don’t address radical ways of detaching property from claiming space and rights, architecture will remain unsustainable. For me this is the spatial factor that underpins many forms of inequality – social, ecological, economic. I believe that once people have the right to claim space — that is to exist, occupy and simply be — outside of the engrained idea of claiming linked to property ownership; there lies an opportunity for maintaining that space with a sense of care, or as Judith Butler describes in her Force of Non-violence (2020), an interdependency and sense of grievability. I recently wrote about this ethos of interdependency in The Architectural Review issue on Care (March 2021) expanding on how shared responsibility is critical to sustainability and architecture in my opinion is useless if not socially and ecologically sustainable. However, given my choice of trajectory in spatial practice, I do hold an optimism and believe that architecture has a role to play in imagining social and ecological equality in how it builds, records and disseminates.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

Make a concerted effort to record. This may be in a variety of mediums. I found that by writing in a journal, I could make my spatial reflections clearer and legible in my work. I often go back to some of these writings, and use them to explore new ideas employing fiction and reality as modes for experimenting. Then there is also the recording of soundings as a mode of reflecting on space. I would encourage young students to tell stories and archive in audio. I find that there is so much description in tone — describing context, time and situation — which creates rich motifs for uncovering and reflecting in the future.

How do you perceive yourself as a female architect working in a male dominated field?

I do not see this just as a gender question. I am and will (whether I want to or not) always be conscious of my presence as a Black woman in a white (male) dominated field. We can’t sever gender from race. Parity is only possible when it is intersectional. I think of a poem by Rupi Kaur that I recently read about the tokenism of non-dominant members of society into oppressive and untransformed systems as an attempt to co-opt and claim transformation.

I am very weary of this as a Black woman in this industry, and therefore put my skills, interests and capabilities at the fore when initially presenting myself. Of course, this is largely influenced by my context as I speak from where I come from, and that is from a voice that isn’t reflected in traditional architecture. A much needed increase in the presence of marginalised (in this case Black woman) capable and qualified spatial practitioners is the only way I see us meaningfully practising intersectionality in this industry. The hope is to create more accordance between the technical producers of the built environment and occupants of the built environment who play a significant role in determining the qualities of space. Ultimately, architecture and the production of space needs to become more diverse to reflect the increasingly diverse world we live in. Intersectional practices, collectives and organisations dedicated to anti-racism and intersectionality have been spaces of care, inspiration and personal progress for me. Matri-Archi, Sound Advice, The Architectural Review, Local Studio, The ETH Parity Group and Hunguta Collective are a few of many that come to mind who engage in transformation with the long-term in mind.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

Currently bookmarked project: Race, Space, Architecture (digital archive project) by Huda Tayob, Thandi Loewenson and Suzie Hall.

Some people I remain inspired by: Klearjos Papanicolaou and Nitin Bathla (co-directors of ‘Not Just Roads’ ethnographic film documentary); Maxwell Mutanda (multi-disciplinary artist); Duduetsang Lamola (visual artist in Cape Town).

Some collectives I’m excited by: Uhuru Heritage (collective in South Africa); Resolve Collective (collective in London); Sound Advice (collective in London), Future Architecture Front (collective/movement in UK).

Practices I find meaningful and interesting: Studio8Fold (practice in London/Berlin); Caukin Studio (practice in Canada, UK and Indonesia); TEN (practice in Zürich); Local Studio (practice in Johannesburg); Creative Assemblages (practice in Uganda).

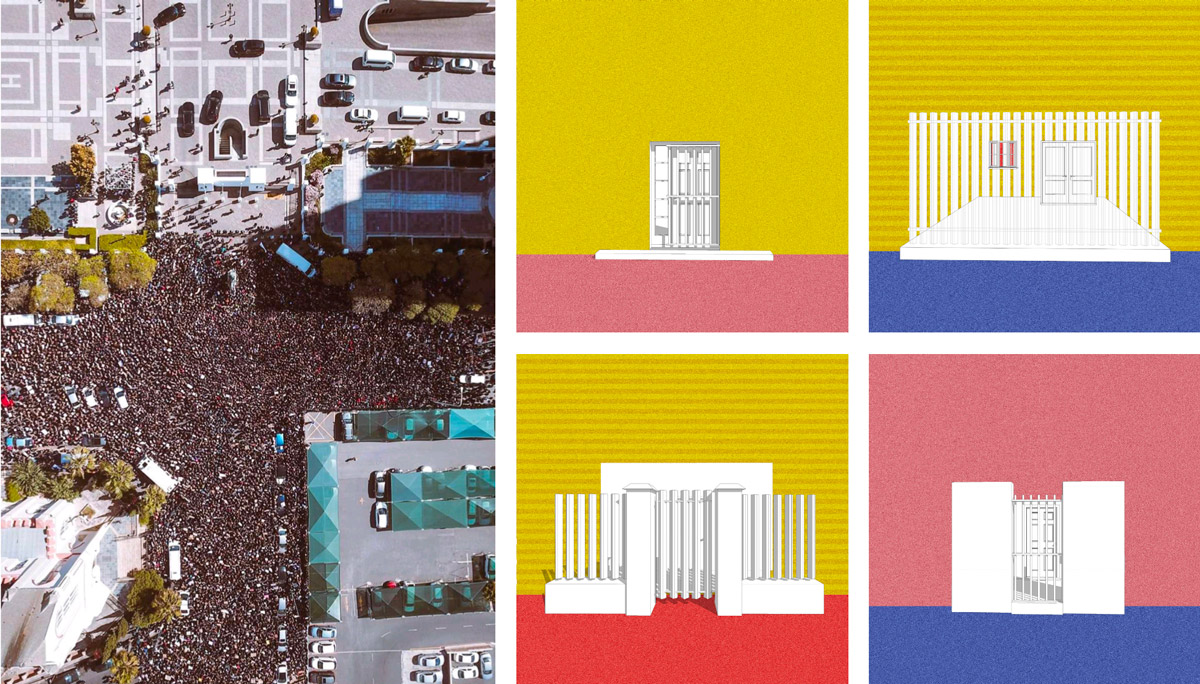

Project 1

Public aGender

Public aGender focuses on the long- standing issue of Gender-based violence. In the wake of the Covid-19 global pandemic the binary between the public and private has been reinforced. The concern lies in the projection that, so long as the hyper reliance on ‘home’ remains, domestic violence threatens the physical lives and mental well-being of women and children living with abusers. The research employs a two-fold methodology: a digital ethnographic approach that gleans multiple perspectives from women of colour gender-based violence (GBV) survivors in Cape Town; and a case study of the Frauenhäuser in Switzerland which are a network of women’s safe houses providing shelter and services to GBV survivors.

From these processes the research suggests a new typology for safe space in Cape Town. The overall outputs include a digital platform for generating typological ideas on safe space, and a speculative project exploring this safe space typology. Public aGender is a research project that has been initiated by my ongoing MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design, intending to develop long-term.

Project 2

Southern Ecosystems

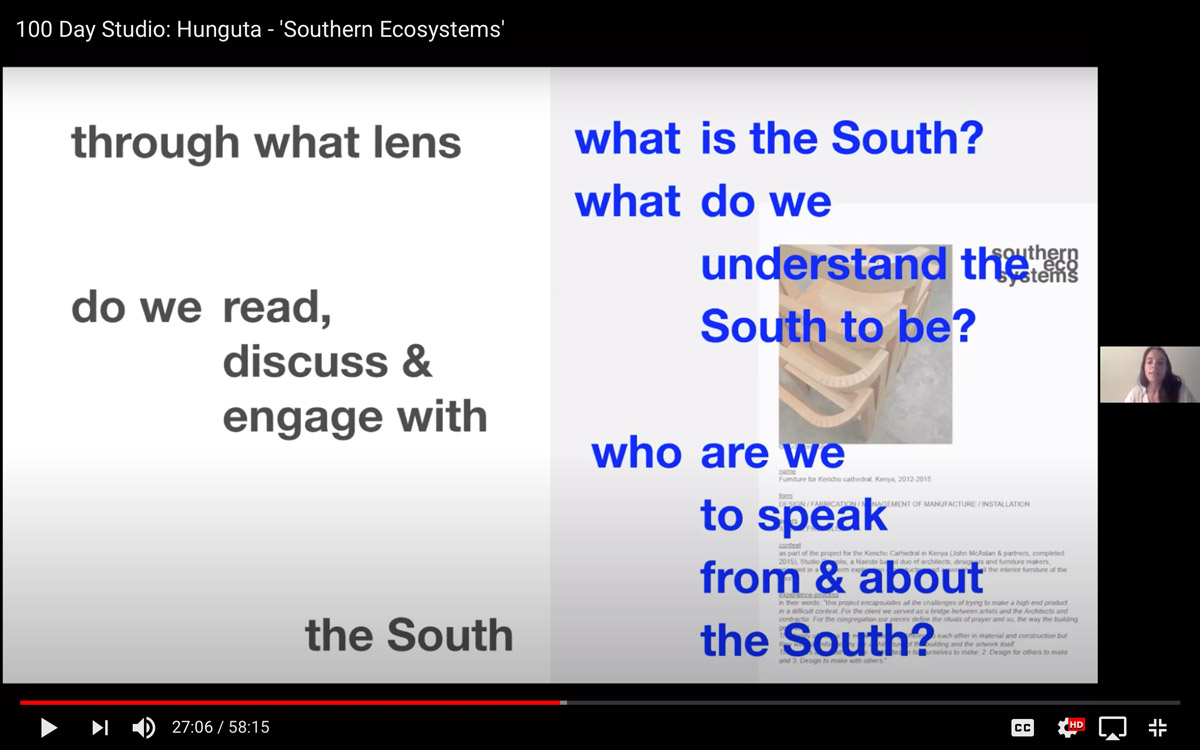

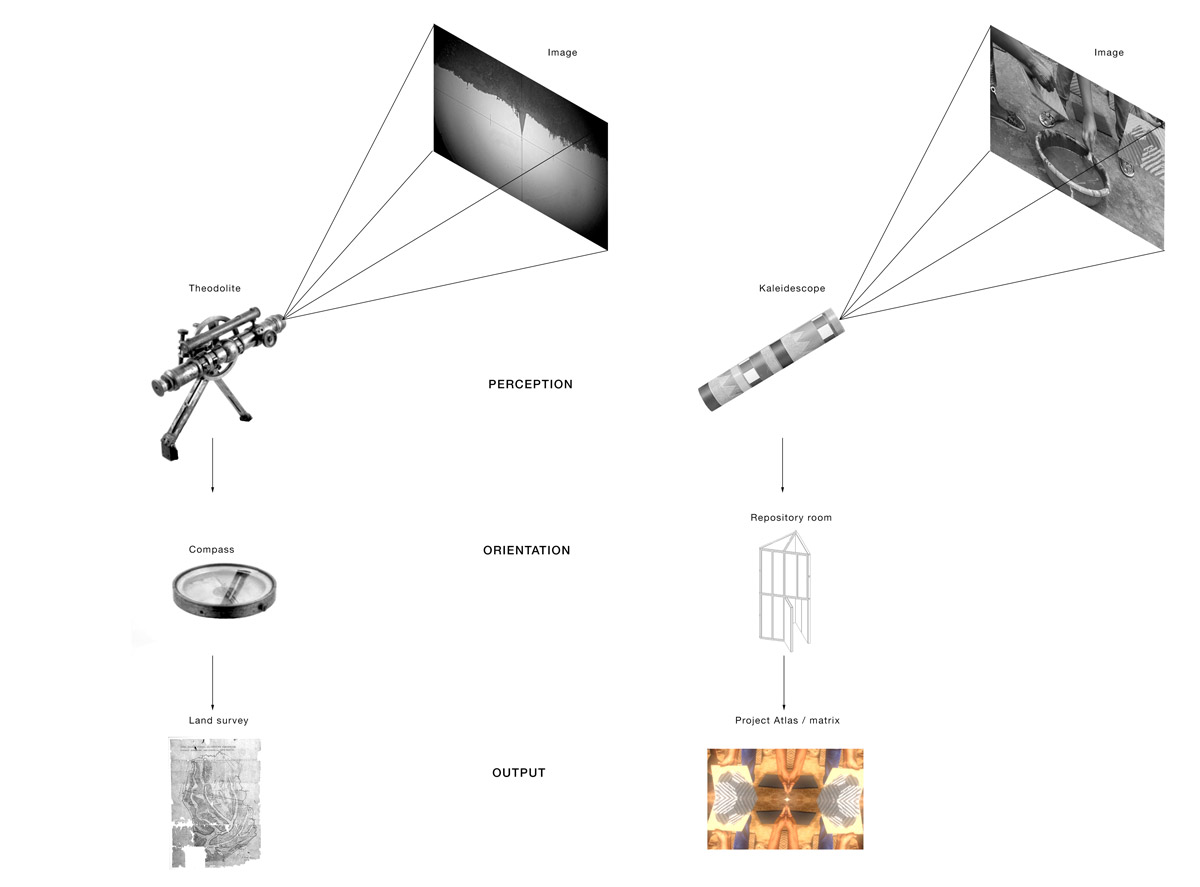

As a multi-disciplinary team (Hunguta Collective: Khensani de Klerk, Tomà Berlanda, Nerea Amorós Elorduy, Tao Klitzner, Scott Lloyd, Maxwell Mutanda and Sunniva Viking) our intention was to question how the concept of degrowth is understood in, and embodied across, the spatial practices of ecosystems in sub-Saharan Africa.

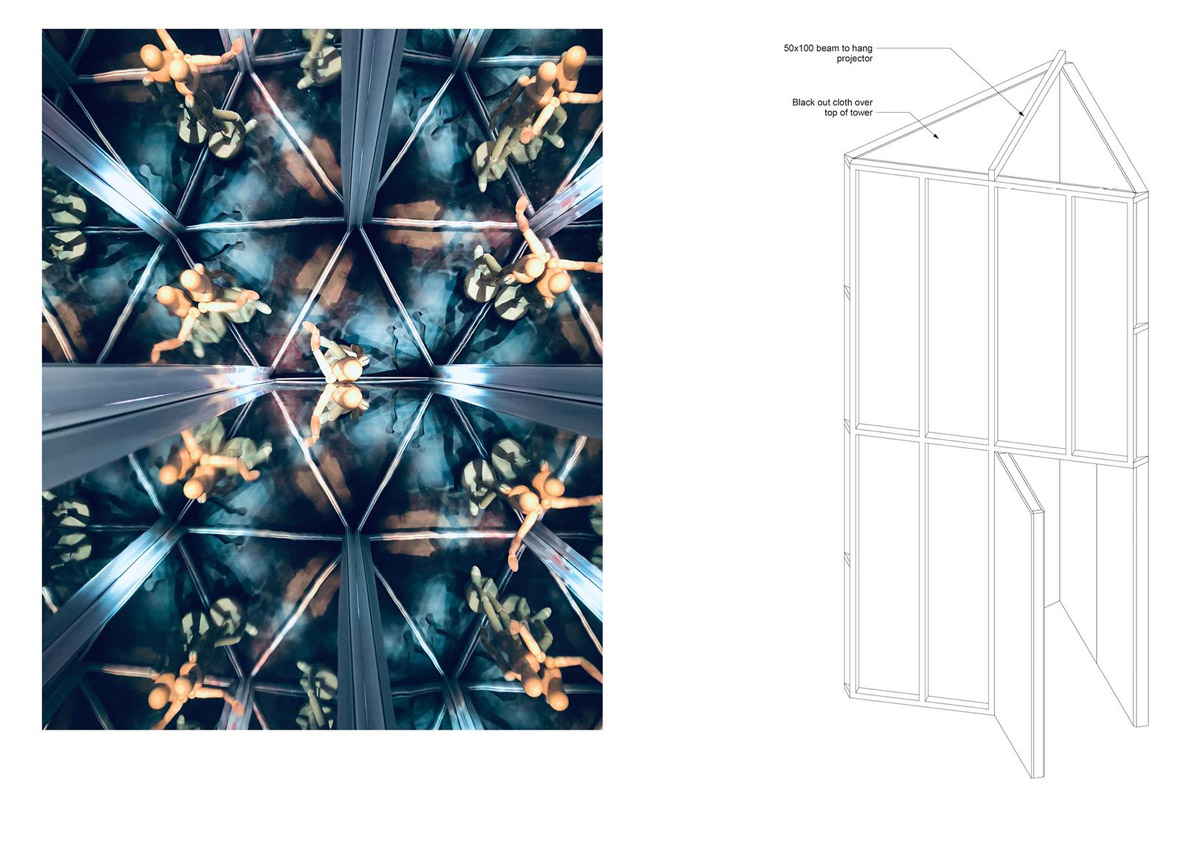

Envisioned as an unconventional spatial experience allowing for multiple readings, the dynamic and interactive installation will offer the audience access to a collection of novel case studies. By challenging the reading of the South through the divisive lens of the colonial theodolite, the project presents a living atlas, a learning tool that subverts established modes of conceiving degrowth as an easily transported, translated, and imposed paradigm. The project was developed for and exhibited at the 2019 Oslo Triennale in The Library.

100 Day Studio Lecture, Hunguta Collective, 2020

100 Day Studio Lecture, Hunguta Collective, 2020

Diagram by Hunguta Collective, 2019

Diagram by Hunguta Collective, 2019

Kaleidescope model, Hunguta Collective, Axo drawing: Matthew Dalziel (Interrobang)

Kaleidescope model, Hunguta Collective, Axo drawing: Matthew Dalziel (Interrobang)

Website: khensanideklerk.com // matri-archi.com

Instagram: @khen_dek // @matri-archi

Facebook: @matri-archi

Photo Credits: All images by Khensani de Klerk unless stated otherwise

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 06/2021