20/018

Vernacular versus Vernacular

An Essay by Prof. em. Karl-Heinz Schmitz

Bernhard Rudofsky’s book title «Architecture without architects» still conjures up potent images of vernacular architecture, mostly exotic and off the beaten track. Rudofsky’s book was written in the 1960’s when Roland Rainer was exploring vernacular architecture in the Burgenland and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were writing «Learning from Las Vegas». Common to all three was the concern that top down mainstream modern architecture was not showing the anticipated results. One of the criticisms was that modern architecture demonstrated little concern for local tradition or for local characteristics. Modern architects favoured the exceptional building rather than contextual building, the singular building rather than urban morphology.

Rudofsky and Rainer were exploring the traditional vernacular, which sets them apart from Venturi and Scott Brown who were investigating a new commercial vernacular, which they believed to be, «as important to architects and urbanists today as were the studies of old medieval Europe and ancient Rome and Greece to earlier generations. Such a study will help» they wrote, «to define a new type of urban form emerging in America and Europe, radically different from that we have known; one that we have been ill-equipped to deal with and that, from ignorance, we define today as urban sprawl.» [Robert Venturi Learning from Las Vegas p. xi]

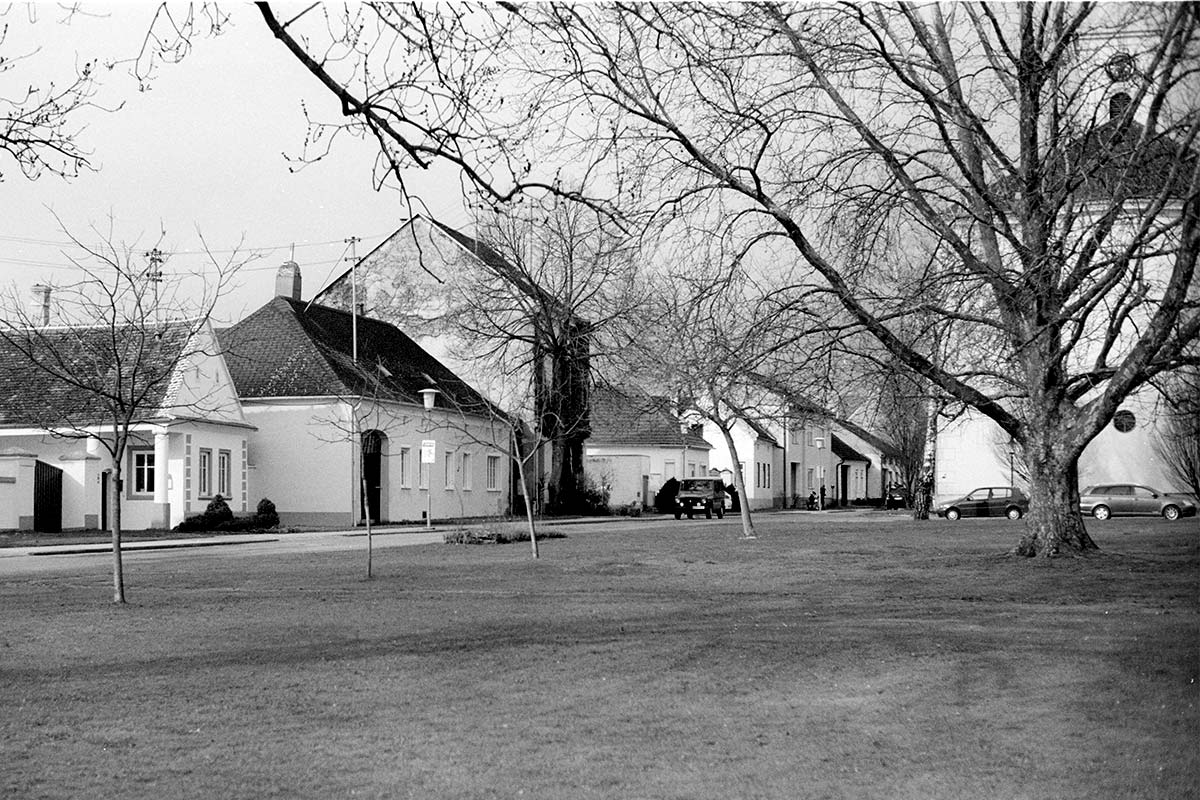

Today, 50 years later, we still seem to be ill-equipped to deal with this problem and the belief that twentieth or twenty-first-century vernacular architecture could form an alliance with modern architecture will once again disappear fairly quickly when googling the images of the Austrian village of Lutzmannsburg. Google gives us an unfiltered and uncritical impression of architecture without architects today. Present-day vernacular doesn’t have the sense or the patience to develop gradually from the simple to the more complex urban form and it doesn’t depend on collaborative and iterative processes, as did vernacular architecture before 1900. Contemporary vernacular neither thrives on enabling constraints and local tradition, nor can it develop over successive generations as a result of natural selection, because it is driven by the ideology of newness and the workings of a modern market. It thrives on fashion and on a superficial understanding of tradition; it thrives on everything that has been foreign to old vernacular architecture, and it remains short-lived.

There are two faces to villages such as Lutzmannsburg. One: the simple, rural, elegant unpretentious buildings carefully crafted into local settings, buildings that have come about by means of hard-won knowledge, typical only to one region. The other: the new commercial vernacular characterised by a cheap imitation of tradition, either garish and pretentious or bland and insipid, always showing an impassive adherence to building bylaws that are not founded on strong urban concepts but on the weak supposition of being capable of circumventing the worst.

Since the 1960’s, historical vernacular architecture has moved out of its passive role of just being there, unnoticed by the history of high culture. Since then, thanks to Rudofsky and Roland Rainer, it has been lifted out of obscurity thereby reminding architects that vernacular architecture can be critical as well as reflexive – critical of modern high architecture and critical of commercial vernacular. Since the 1960s, architects began to realise that they could learn as much from anonymous and unpretentious buildings as they could from pedigreed and well-publicized architecture.

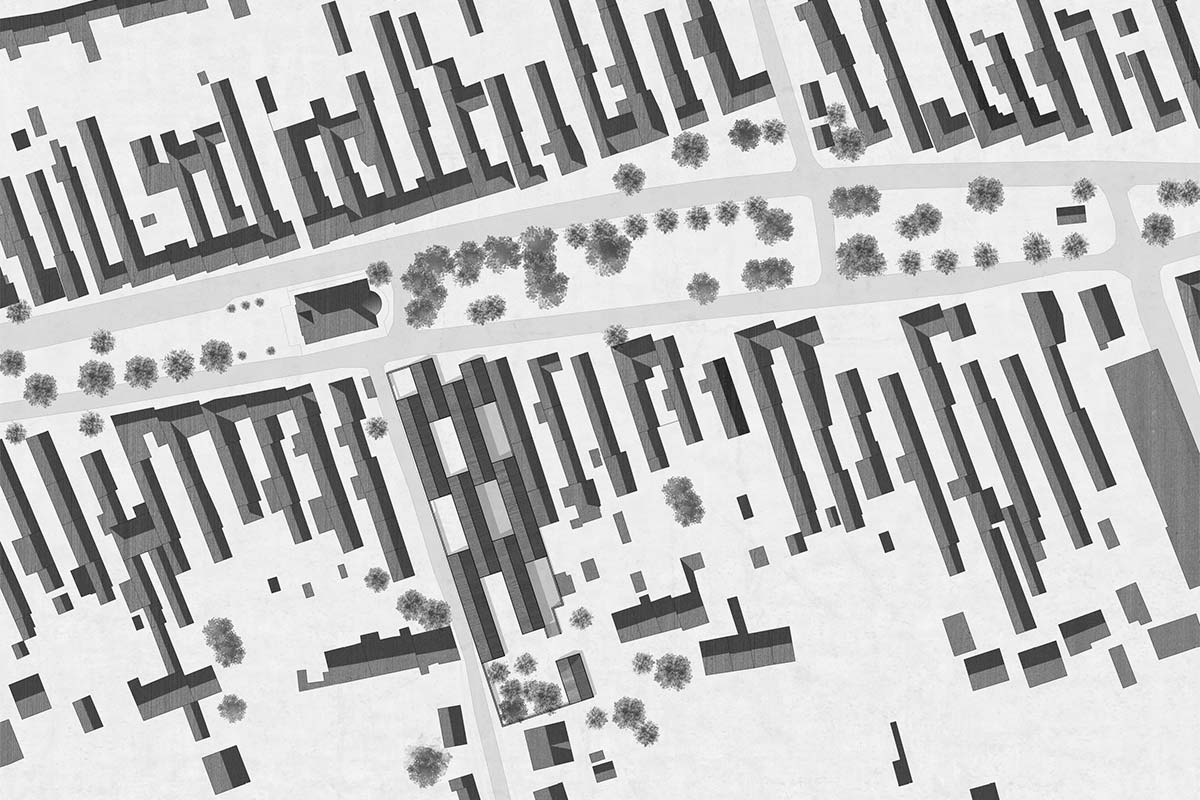

The lessons to be learnt from Bernhard Rudofsky and Roland Rainer are quite simple, namely that the urban context is as important as the urban monument and that the identity of place is as important as the identity of the object. In other words, that a grasp of urban morphology is vital to the understanding of place.

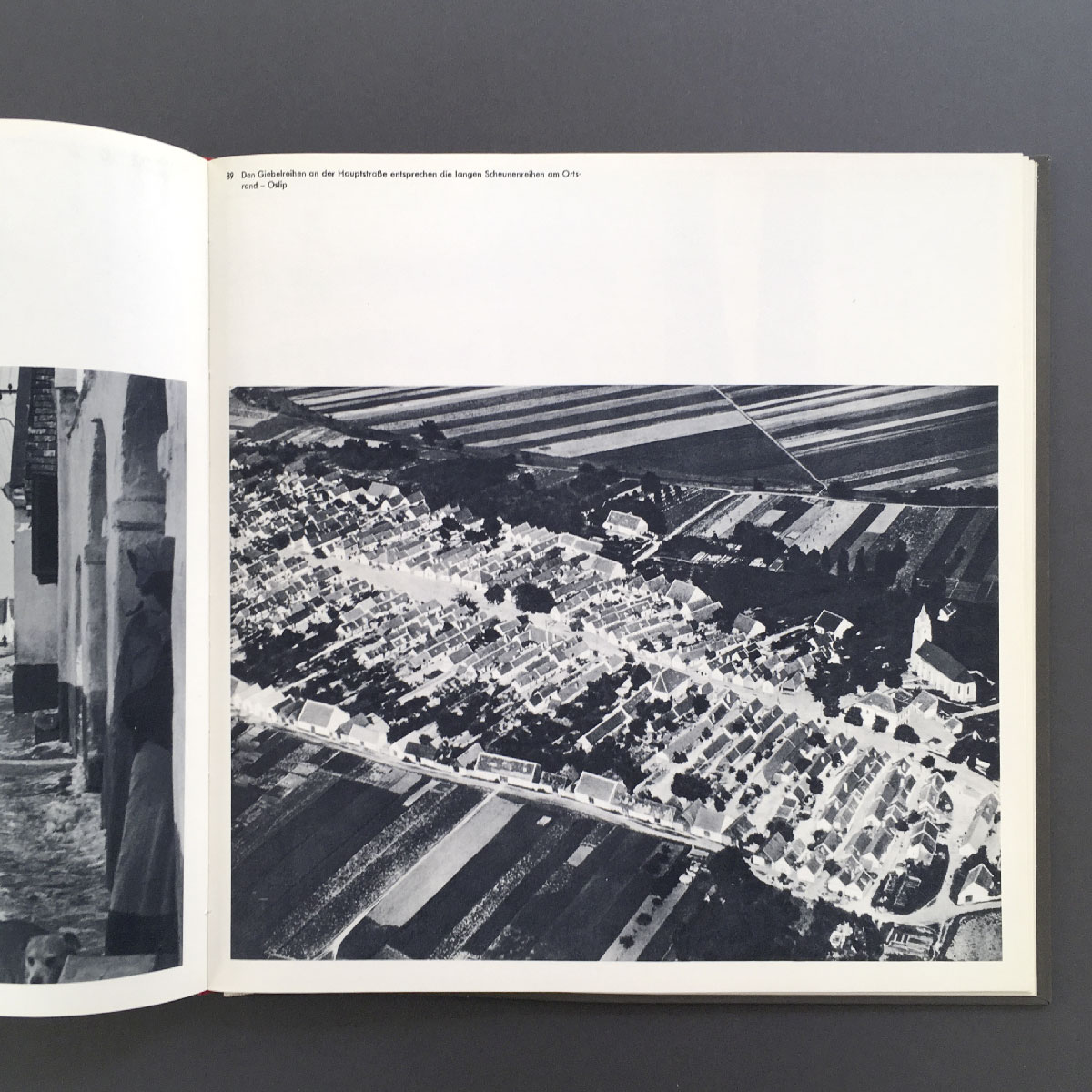

The lessons to be learnt from a village like Lutzmannsburg are equally simple: stimulating and dynamic urban agglomerations, no matter how small, will need at least two building types and one common space in order to establish a basic level of urban complexity. In the case of Lutzmannsburg the village green is the common space that centres and stabilizes the main mass of buildings, contributes to their urban identity and serves as a natural location for community buildings such as a church or a school. These buildings are usually singular and independent objects.

The other essential building type needs to be a repetitive building, spatially dependent on its neighbour, in other words, a type that remains abstract, incomplete, even open as if waiting for completion and thus becoming an inseparable part of an organism. This organism is necessary to define the communal space and this type usually consists of residential buildings or buildings in which people work.

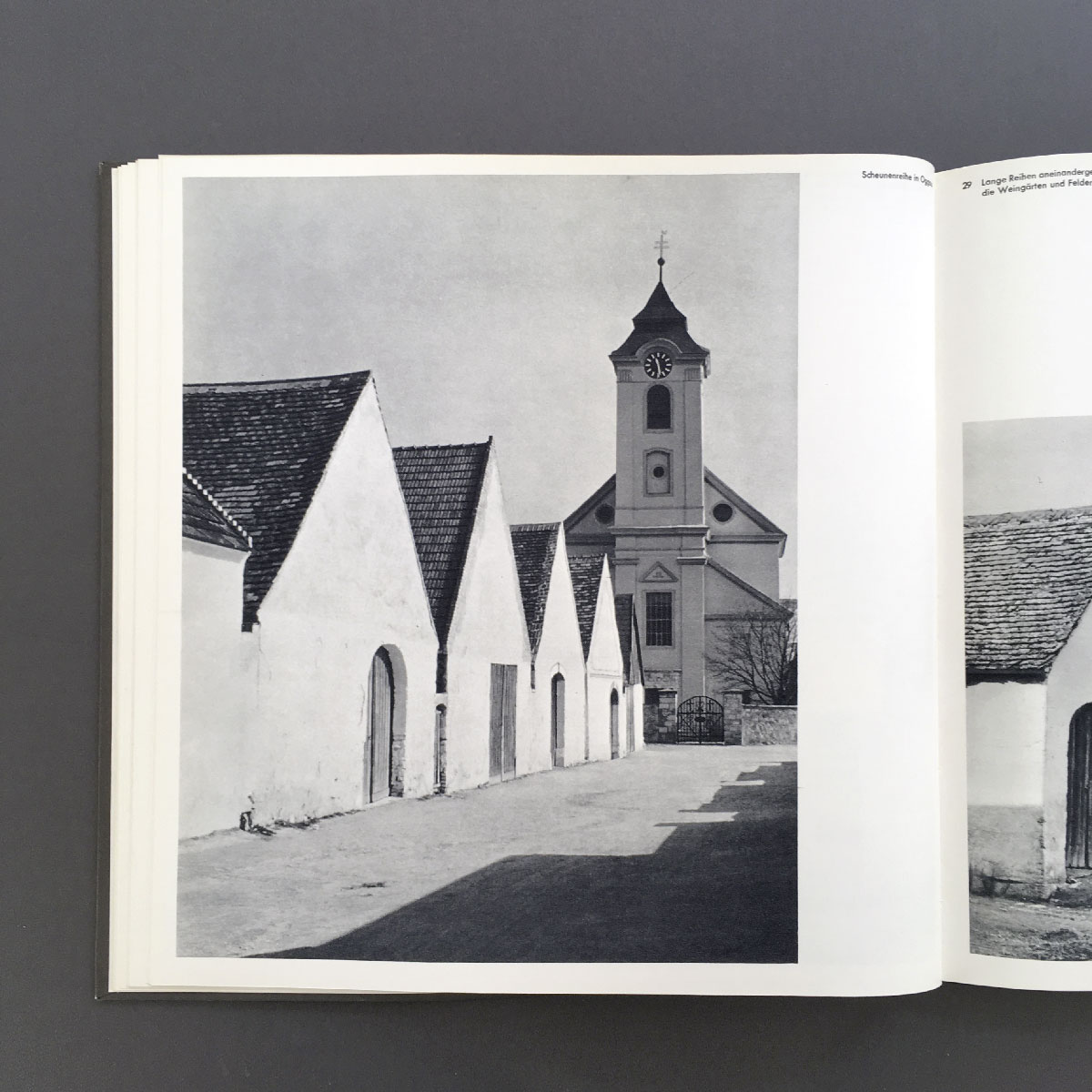

The Barn

The Barn

The Barn

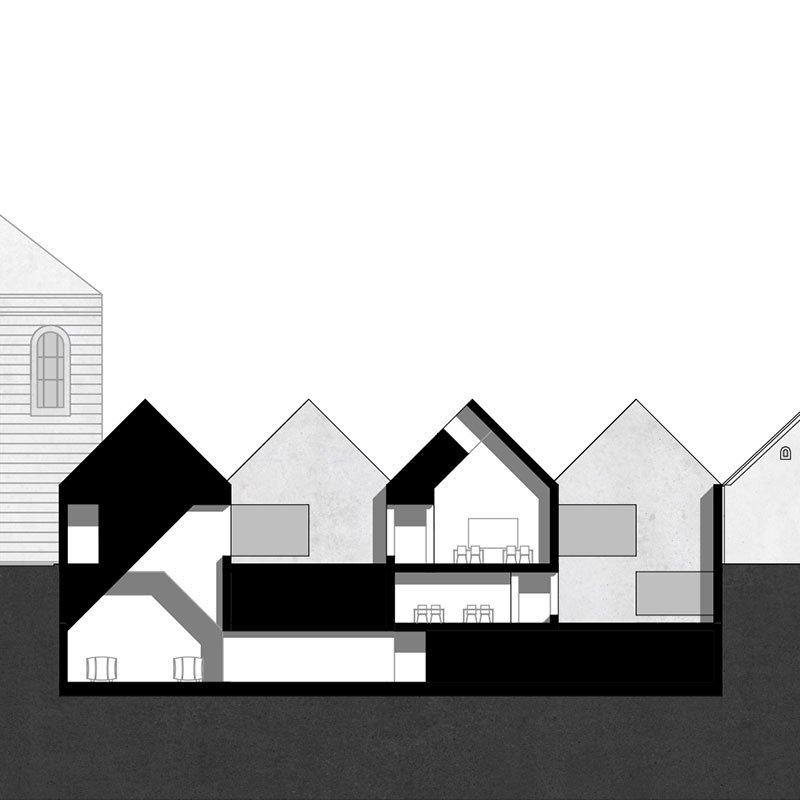

There is one other important building type common to the villages of the Burgenland: the barn. In a farming community this building has its natural location on the outer edges of the village where it can serve both the farmhouse and the field. From an urban point of view the barn has become a formal device to limit growth and to shape the outer edges of an undefined organism, thus adding to the identity of the village structure. Even here, in these small villages, there is a dialectical relationship between the almost amorphous organism of the farmhouses and the clear contour of the church. There is a similar dialogue between the church and the barn, each representing the two extremes of architecture: the exceptional and the mundane.

A school for viniculture

Other than most participating design studios, our studio set out to investigate the integration of a school into the village structure of Lutzmannsburg. This will hopefully complement the design investigations into housing, as an expanding residential village structure will inevitably involve the design of additional public or commercial building types. The integration of other functional types poses a special challenge to the village, as there is no longer a clear strategy concerning the siting of public buildings. In our case, two sites seemed feasible: the site of the old school and the site of the village green.

Karl-Heinz Schmitz

Weimar 2014

Previously Published in «Village Textures» by Schlebrügge

Design Project by

Janos Fuchs and

Till Weissinger

Most students chose to accept the corner site of the old school which is situated next to the church but which is also part of the pattern generated by the farmhouses. This raised the question, whether the school could assume a form, which could be totally independent of its immediate neighbours – the farmhouses – or whether it would strengthen the general pattern thereby losing some of its own identity.

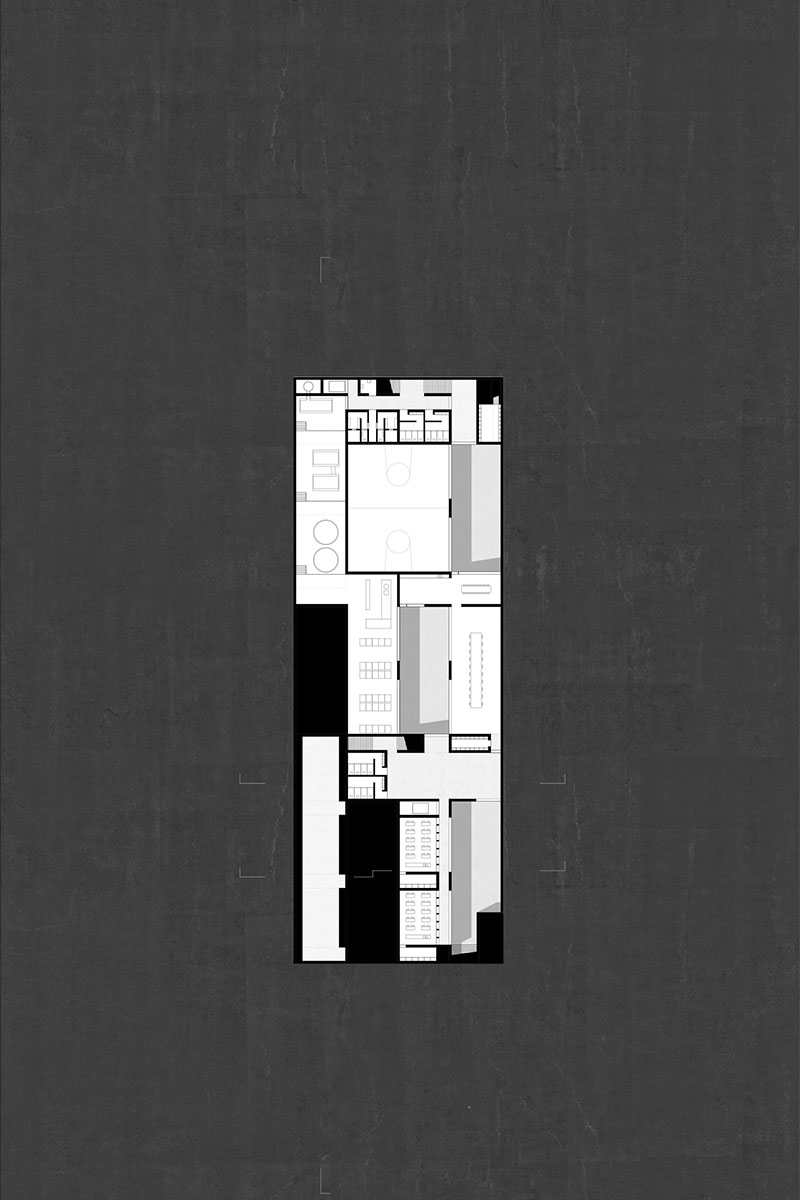

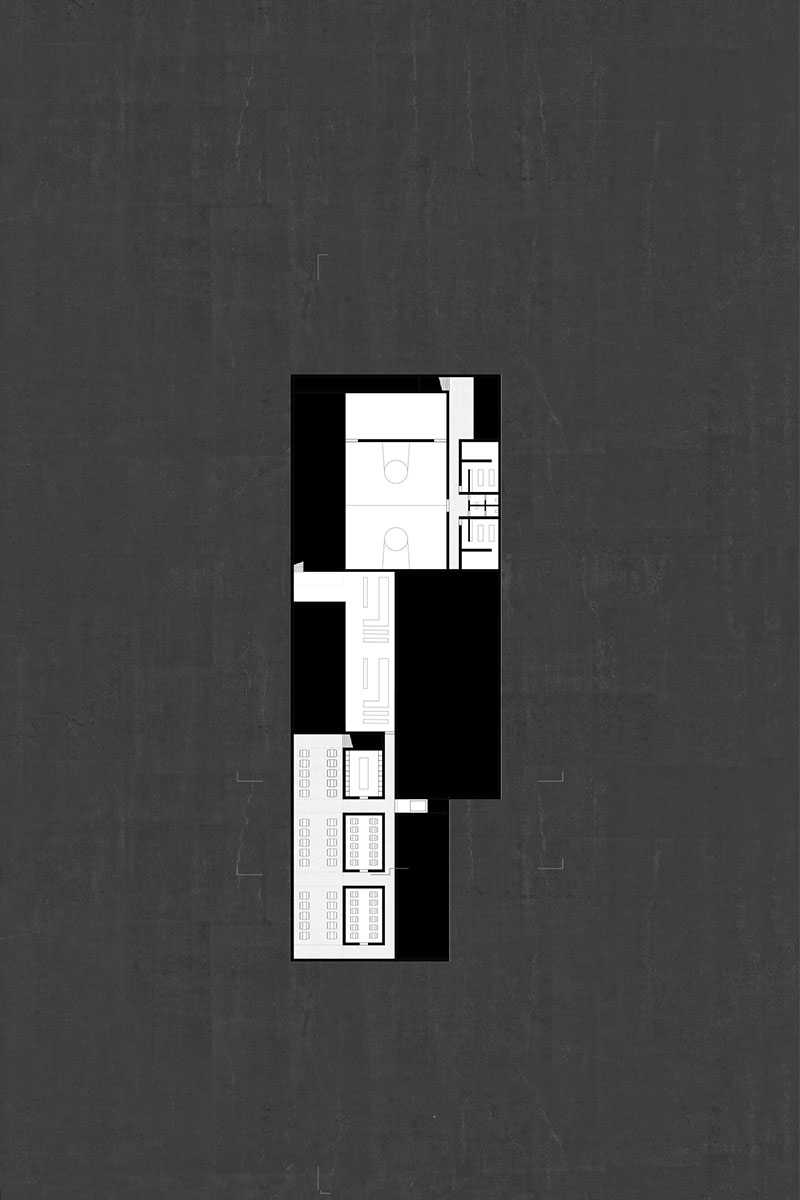

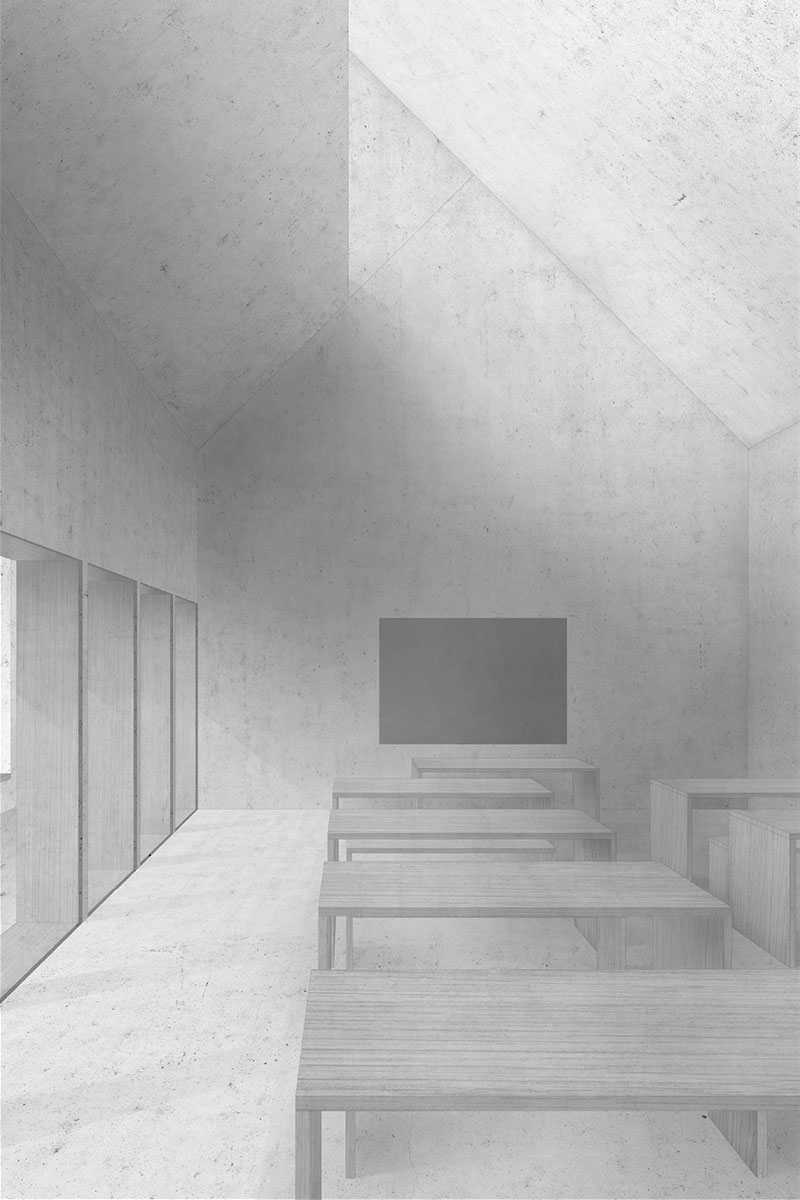

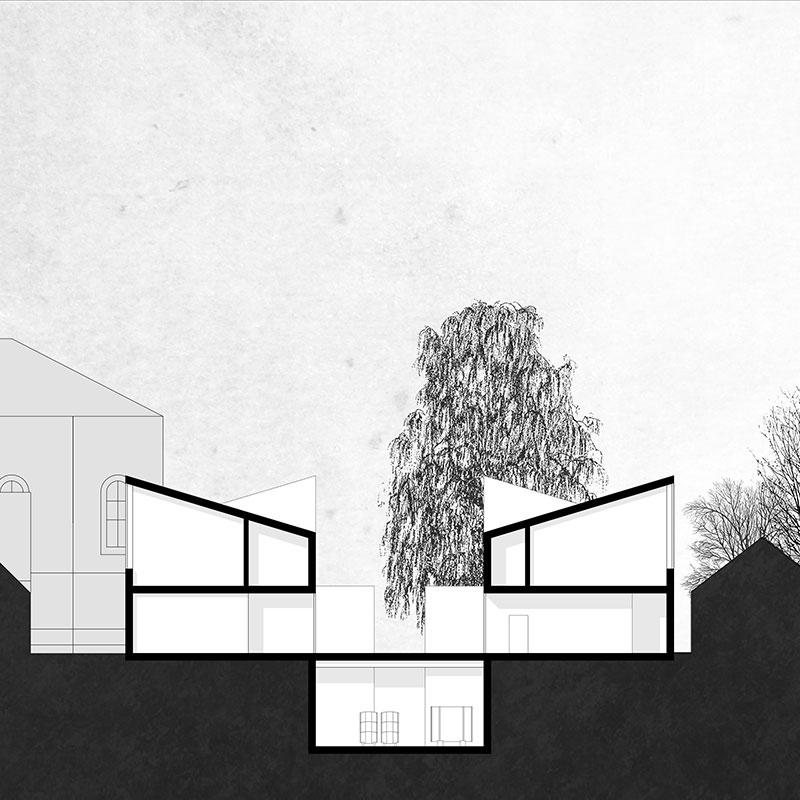

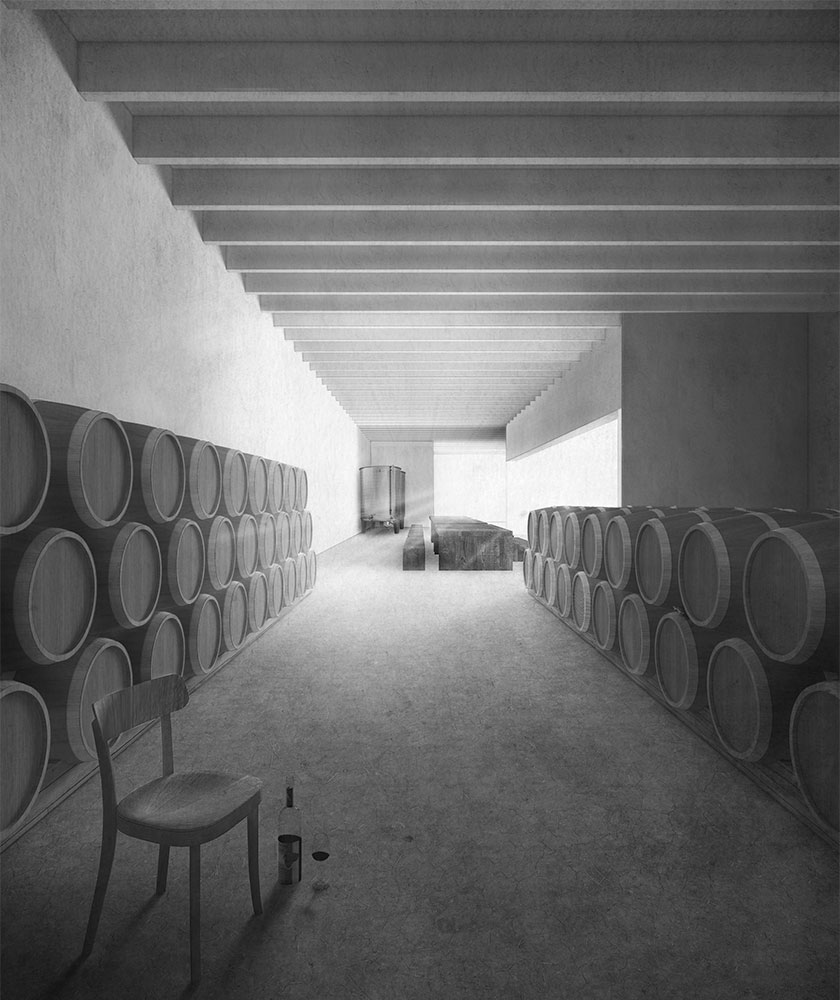

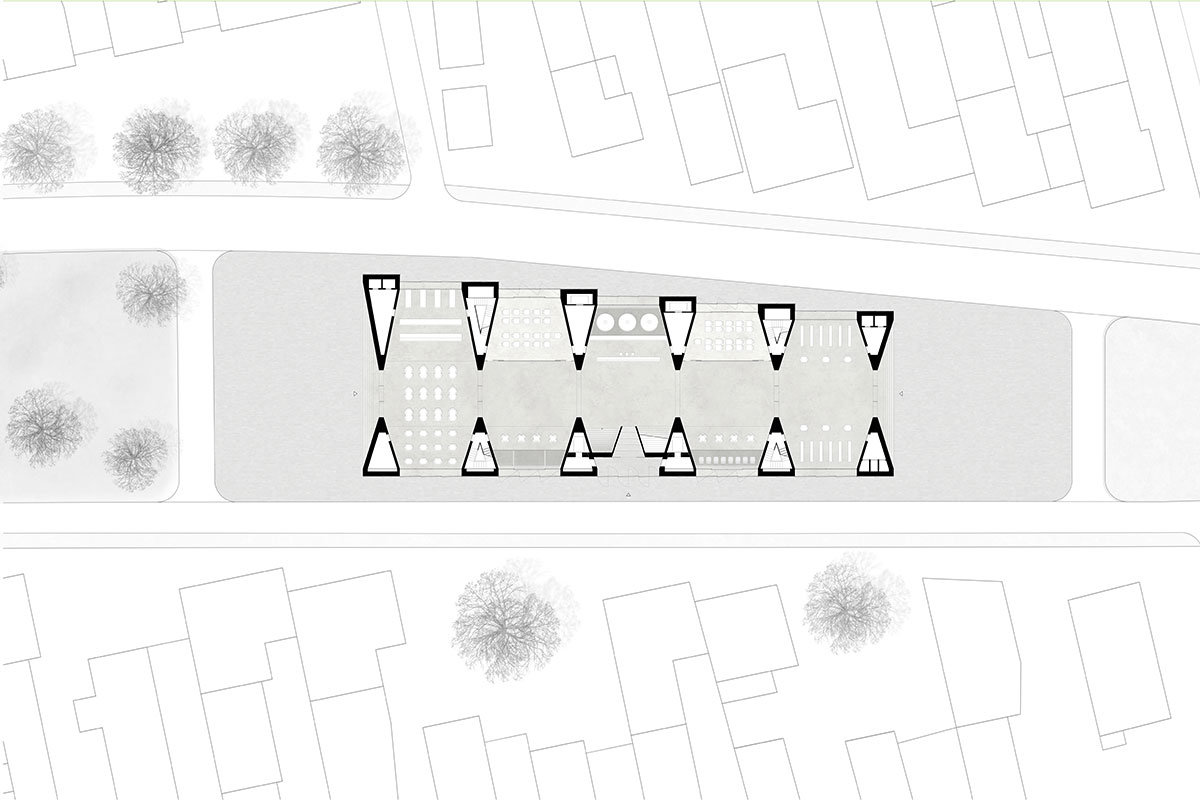

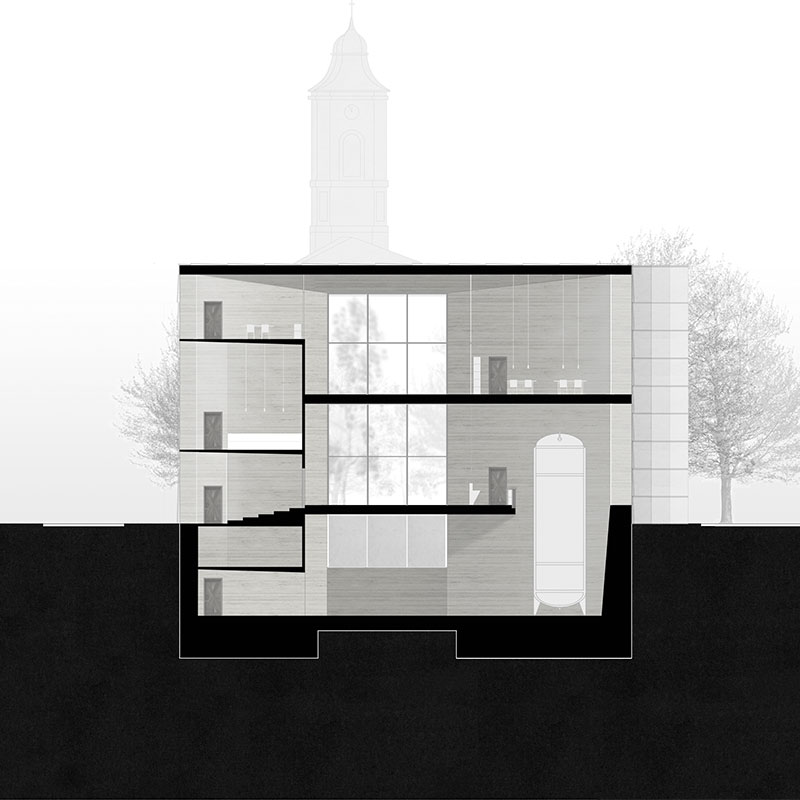

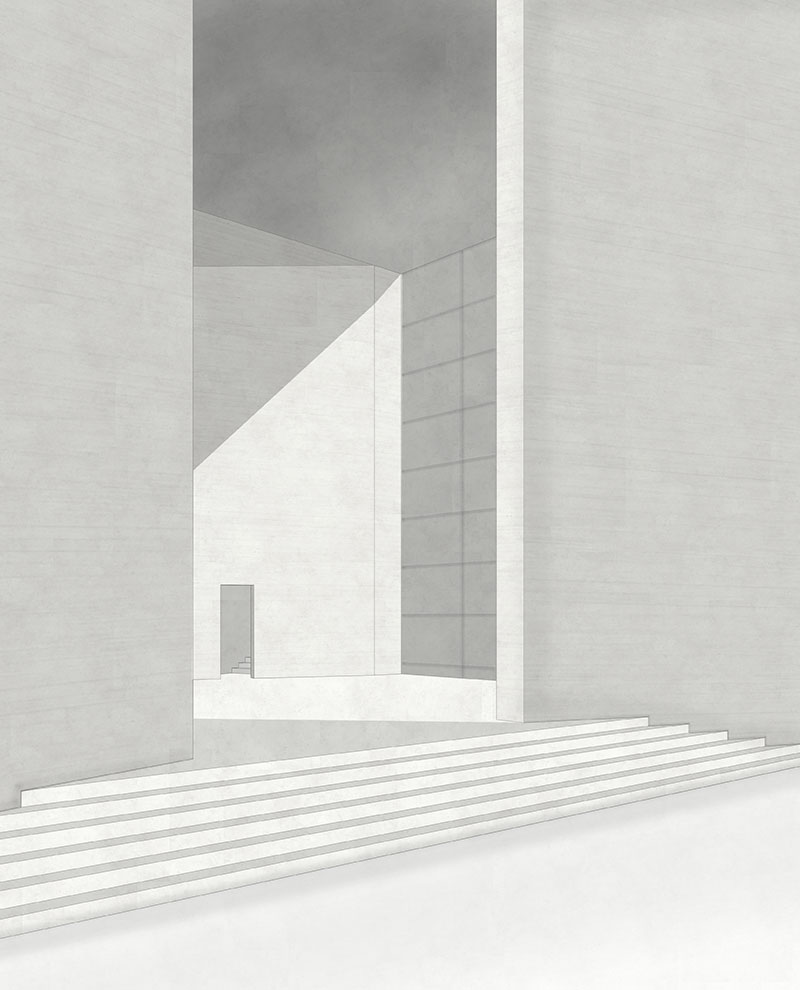

Janos Fuchs and Till Weissinger decided to accept the general pattern generated by the elongated farmhouses as the formal and spatial theme for the design of their school. The idea was to transform a limited number of spatial types through a series of manipulations – such as repetition, superimposition, subdivision, permutation, doubling, and reflection. The aim was to accommodate a programme, which would be far more complex than that of the farmhouses. The heterogeneous programme promoted the idea of generating many houses, whilst retaining the concept of a single building when seen from the village green or alley.

Design Project by

Ken Polster and

Maria Seidel

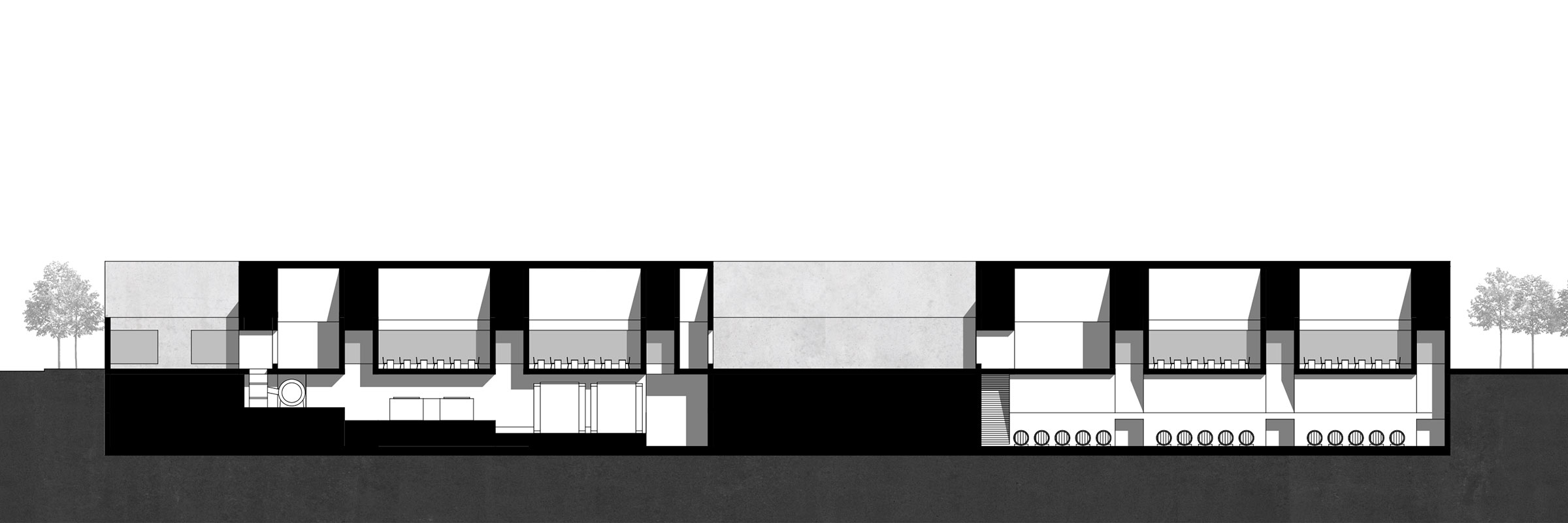

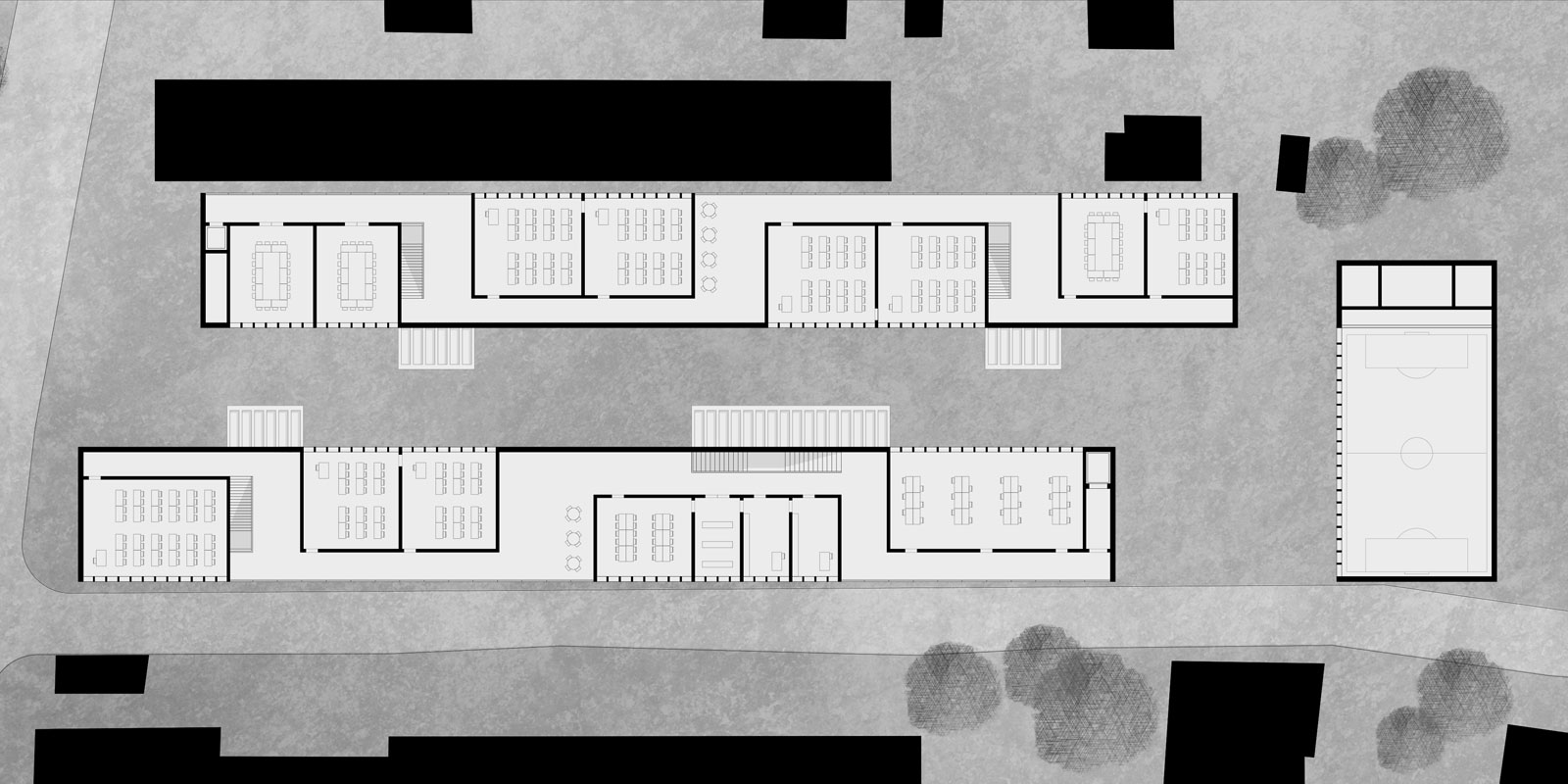

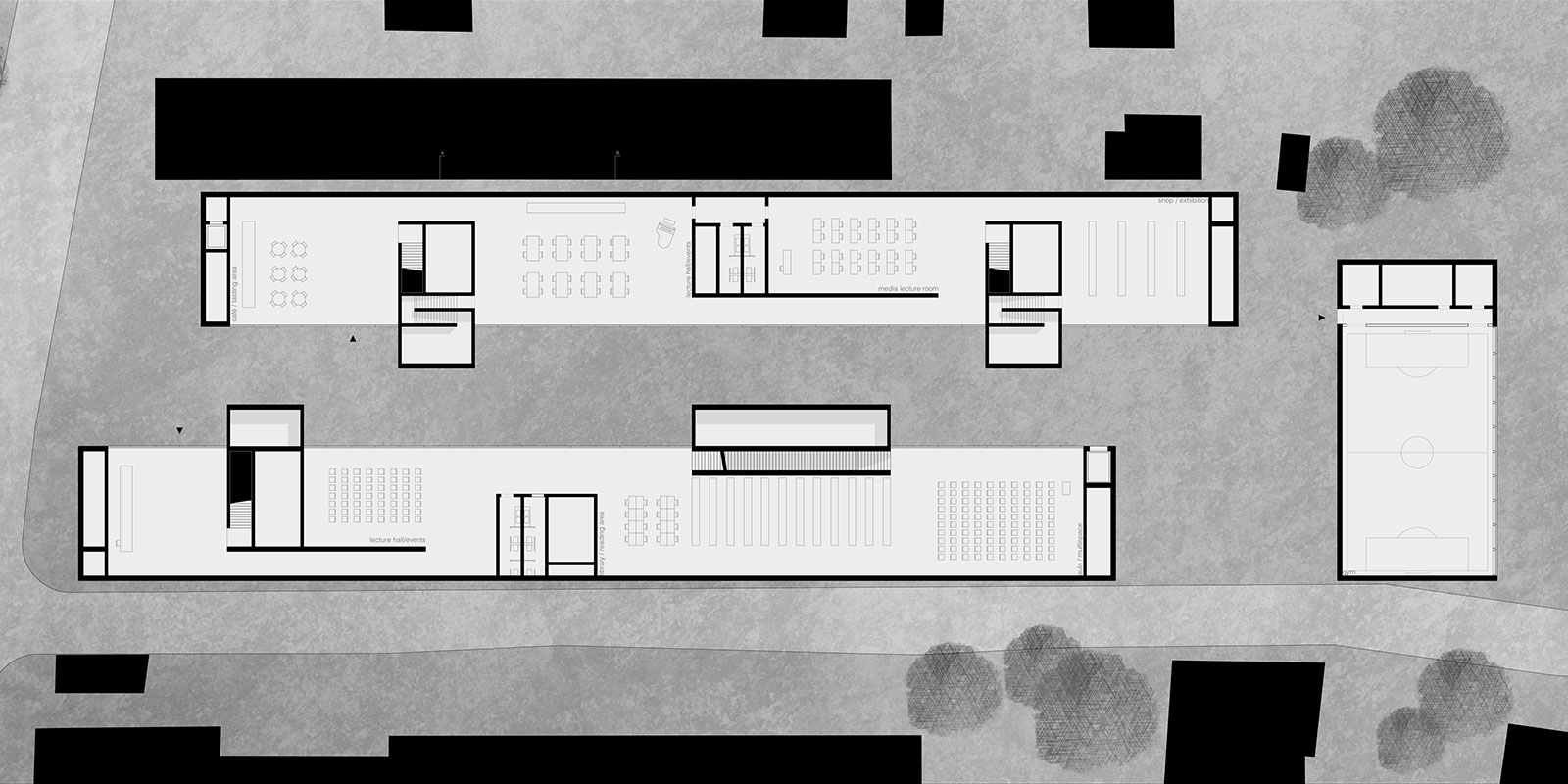

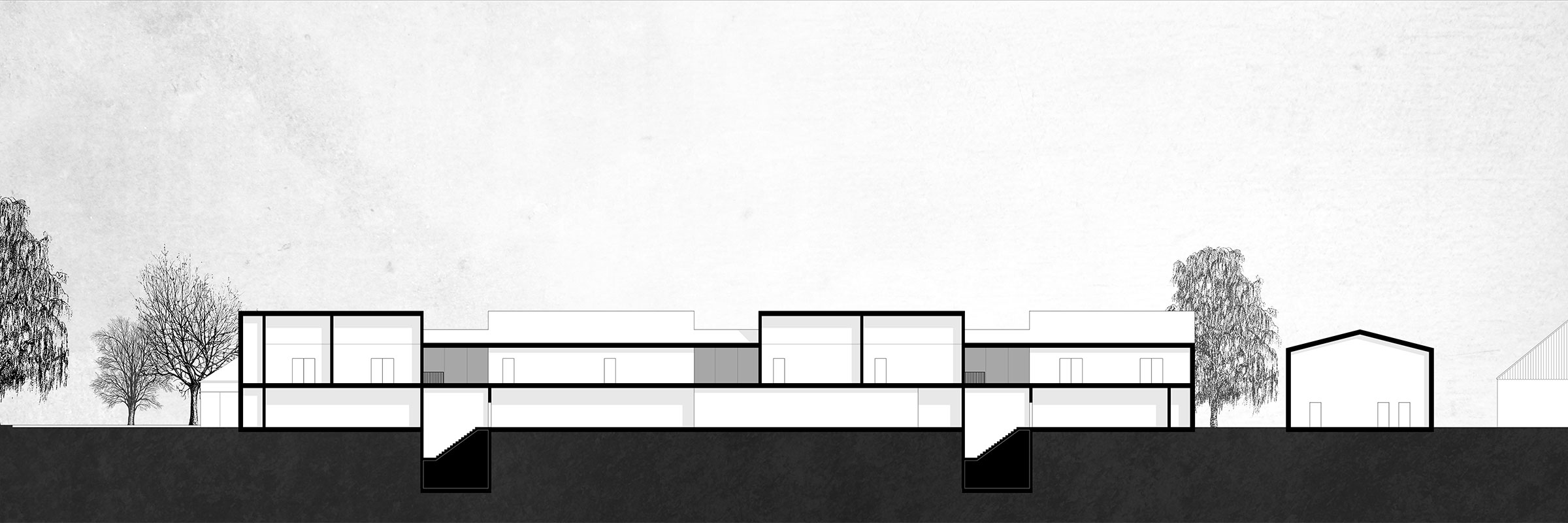

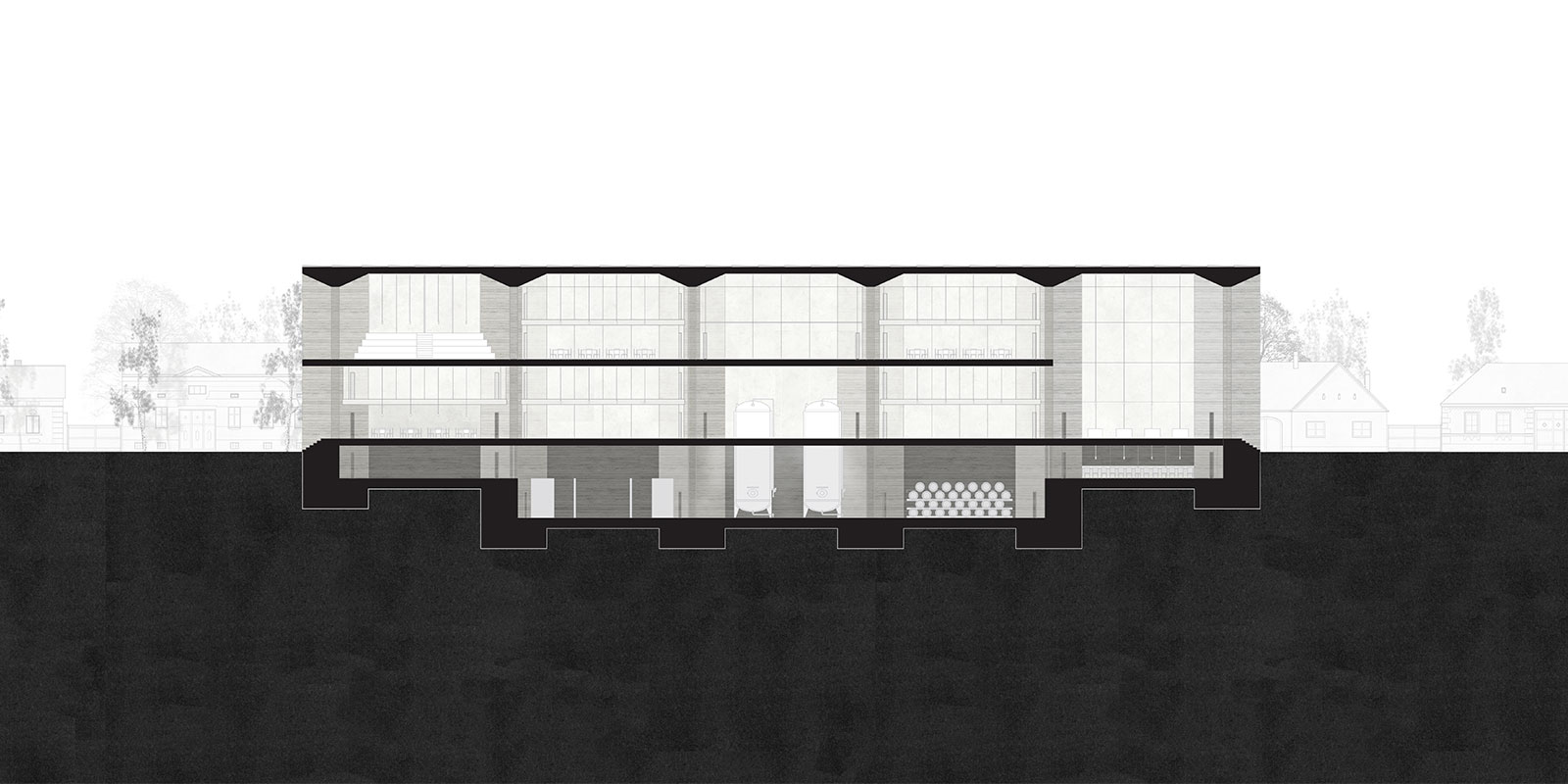

In this design the extensive and complex programme is skilfully organized within two long buildings, which, together with a court of similar proportions, have become part of the traditional morphology of the village. Here however, the court is common to both buildings. Its presence is no longer private or semi-private as with the farmhouses but interlocks with the public realm of the village green.

The floor plans are based on the concept of fusing the open plan with boxedin spaces, thereby giving the impression of a simple programme, in which enclosed spaces are used to organize what appears to be one big space. The students placed the gym at the outer end of the school where, reminiscent of the barn, it limits further unchecked expansion and gives form to the outer edge of the village.

Design Project by