23/015

Marija Marić

Architect + Researcher

Luxembourg

«I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor.»

«I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor.»

«I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor.»

«I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor.»

«I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor.»

Please, introduce yourself…

Hi, my name is Marija Marić. I am an architect and researcher, currently based in Luxembourg, where I work as a postdoctoral researcher at the Master in Architecture Programme at Uni Luxemburg. My practice is organised around the questions of property, real estate, media, and the production of the (built) environment in the context of global circulation of capital and information.

Portrait – Marija Marić – © Teodora Ivkov

How did you find your way into the (extended) field of architecture you are working in now?

That is a great question—I guess I need to go back 15 years to the time when I was still studying architecture in Novi Sad, Serbia. Our programme back then involved many interdisciplinary studios and courses which were bordering with questions of performance, theatre, ephemeral architecture, to name just a few. While still a bachelor student, I had a chance to work with different local NGOs and art collectives on projects that looked into the production of urban space through social, economic, political lenses. After my Bachelor studies, I enrolled into a new Masters Programme in Theory of Architecture and Urban Planning that just opened up at the University of Novi Sad, and after that to a second Masters of New Art Media at the Academy of Arts, also in Novi Sad—both giving me a framework to leave traditional architectural design as a given format to critically work with and unpack the politics of production of (built) environment. During this time, I shortly worked as a research intern in a small Viennese office called Expanded Design, on projects dealing with the histories (and futures) of social housing in Vienna. After Vienna, I moved to Zurich for my doctoral studies at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), at ETH Zurich, where grounds for what I am currently doing has largely been set-up, not just in terms of content but also method.

I started my PhD with a research on socialist Yugoslavia, but spent the first two and a half years questioning what my research practice could be. This period, characterised mainly by reading, conversations, and searching for my interests, and less by “production” expected in the PhD context (writing, giving lectures, etc.)—which back then I did not experience as exciting as I do now, but which was possible only due to very generous time and autonomy we as PhD students had—was really formative for my practice today. During this (and the following) period, my research on societal ownership started to serve more as a base for understanding the post-socialist condition that came to shape cities across former Yugoslavia. Planning and construction of one large-scale real estate development, later to be known as Belgrade Waterfront, embodying this condition in quite a radical form, was taking place at that moment. The clash of visions—whether of global real estate developers in finding another site for profit-making, political opportunism and the myths of nation-making through the construction of square meters, or those who resisted the project claiming the right to the city—opened up an understanding that built environment today is largely produced in what one might describe as a “real-estate-media complex.”

With this expression I refer to the collaborations between practices of real estate speculation and media expertise and technologies that help legitimise these practices. In this process, language plays a key role. The ways-of-talking help construct our ways-of-seeing, thus shaping the ways-of-doing. Reading real estate advertisements for Belgrade Waterfront set the ground for Real Estate Poetry—the project of claiming real estate language as a new literary genre that could help us deconstruct the developers’ visions of profit and growth, paving the way for my PhD research and setting the ground for many of the projects I am engaged in right now.

What comes to your mind when you think about your thesis project?

My doctoral dissertation, titled Real Estate Fiction. Branding Industries and the Construction of Global Urban Imaginaries looked into the role of communication strategists in the mediation, design, and globalisation of the built environment. It was developed under the supervision of Philip Ursprung at the gta Institute, ETH Zurich. I looked into how the role of a real estate media expert has emerged and grown in relevance over the last three decades, into a position in which it often competes with the role of architects and urban planners.

With communication preceding rather than succeeding architectural and urban design in the era of global circulation of capital, goods, information and people—storytelling and language have become design domains running in parallel with that of planning, while branding strategists themselves took over the development of architectural aspects of real estate projects, thus blurring the boundaries between the scopes of work of the two professions. Organised around the case of Belgrade Waterfront, a large-scale urban development conceived in the real-estate-nationalism nexus of the post-socialist Serbia—the thesis framed the two projects as designs of their branding strategists, and not their architects and urban planners.

My work was based on archival research, media analysis and many interviews conducted both with the stakeholders involved in the Belgrade Waterfront project’s development, as well as representatives of global agencies specialising in real estate branding and storytelling. To answer the second part of your question—I think this research has set the ground for most of my current projects, even when the relationship does not seem too obvious.

How do you understand the relation of theory/reflection, practice and teaching in architecture?

To me, this is all one project. I think that, in the end, it is about the questions we are asking and the positions we are taking as researchers, practitioners, activists, regardless of the form these questions take. I remember an incredibly inspiring lecture by Mierle Laderman Ukeles I attended in 2018 at the Migros Museum in Zurich, when this fascinating artist, whose work I was discovering at the moment, talked about almost six decades of so many different works she did—ranging from short manifestos to large landscape-art installations—all guided by a single question: the possibility of maintenance as a form of artistic practice. This was an example of how one’s work can keep research consistency and political relevance, but still operate across different media, audiences and scales.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your work?

This is an interesting question. Angelika, you were recently visiting us in Belval, I would love to hear your impressions! Luxembourg is a country that is developing very quickly, with a lot of new construction taking place on the greenfield and formerly agricultural land, with still not enough strategic consideration on its impacts—from resource extraction, to housing affordability, pollution, to name just some. This can leave a traumatizing effect both environmentally and socially. At the same time, there is a lot of willingness to challenge these, often real-estate driven, ways of working with the built environment, and I think this leaves space for hope and opens great opportunities to do things differently.

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

There are many, but one that I wish to emphasise here is: architects as workers. The conditions of our labor and the possibility of solidarity and care, which I think are just so intimately tied and inseparable from the way we operate in the world. I strongly believe that there is no moving forward if we ourselves do not challenge the conditions and practices of exploitation of our own labor, which are also so characteristic to the production of (and access to) space around us. In other words, instead of working with objects—working with subject(ivitie)s.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

I would recommend to dig into critical thinking, as a tool to always try to challenge what is given. Consciously reflect on your own historical specificity of what does it mean to study, to be a student, both individually and as a member of a community of those who share your conditions (read bell hooks and Paulo Freire).Care, for yourself and for others. Don’t be scared of friction and disagreement. Learn how to work with words and across different media—a lot of “architecture” happens beyond the visual.

Project 1

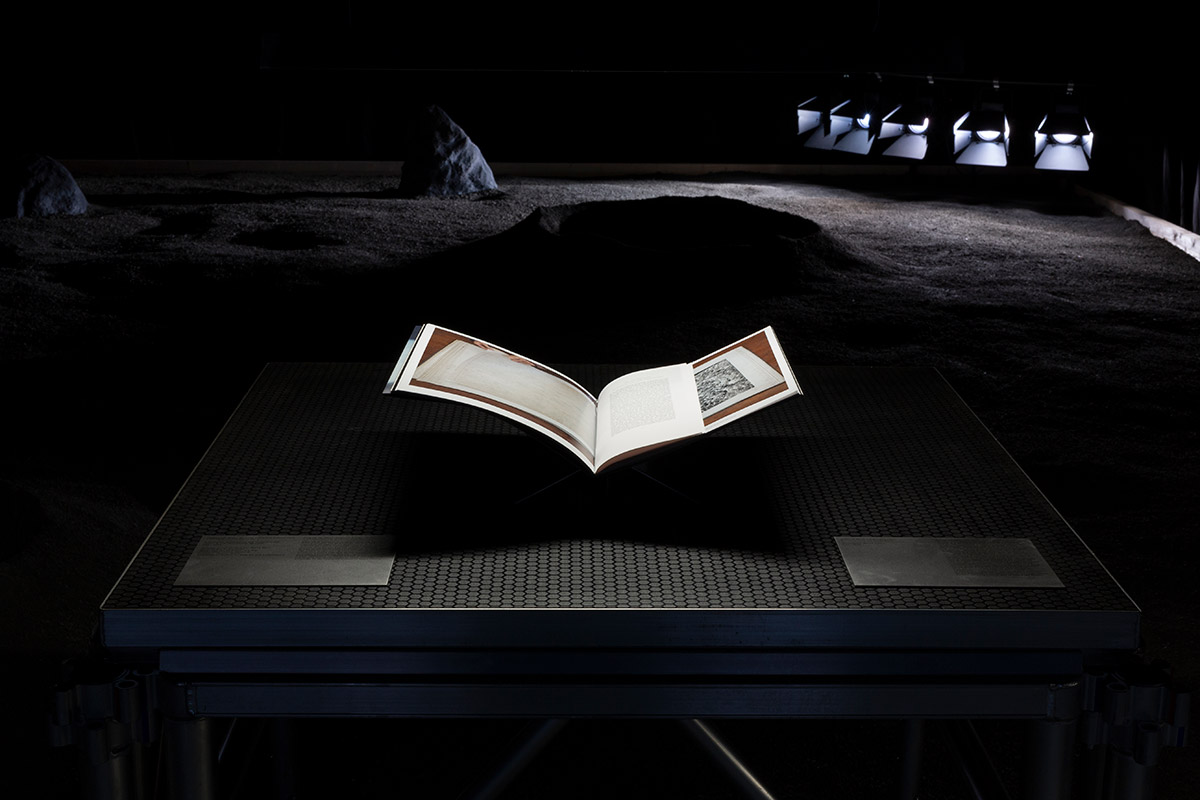

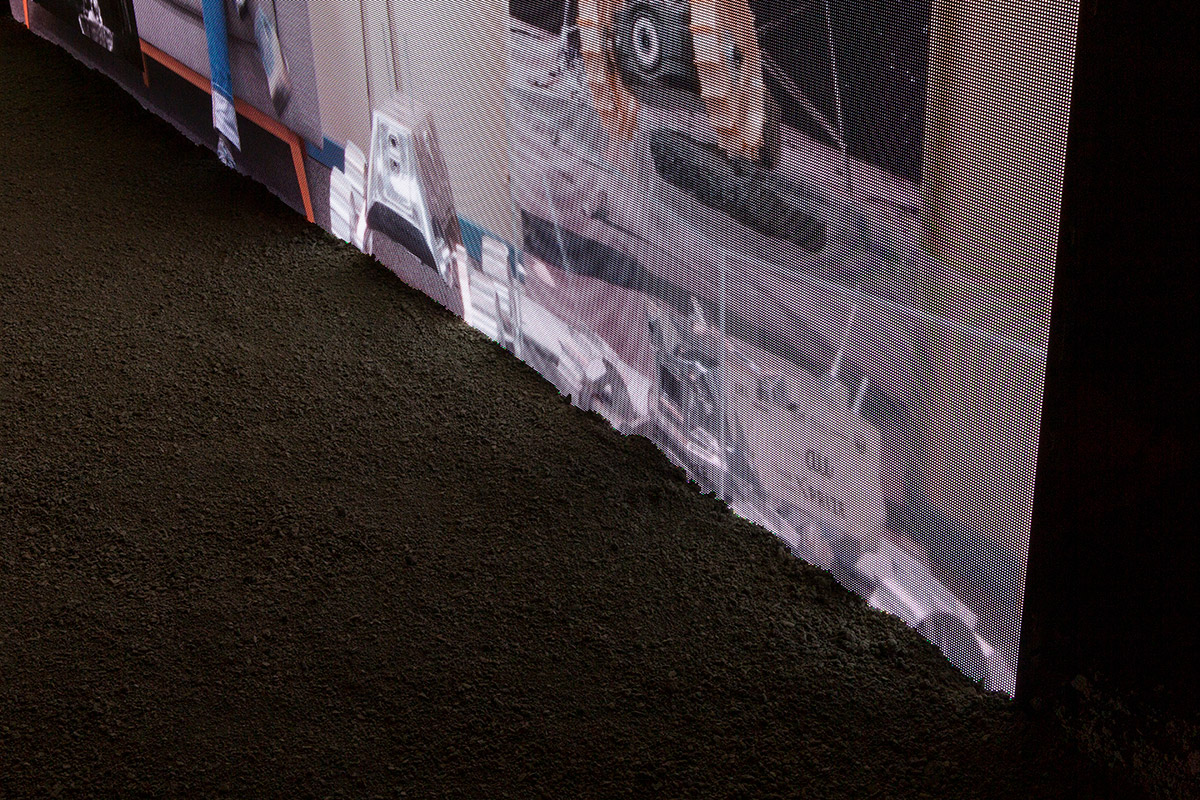

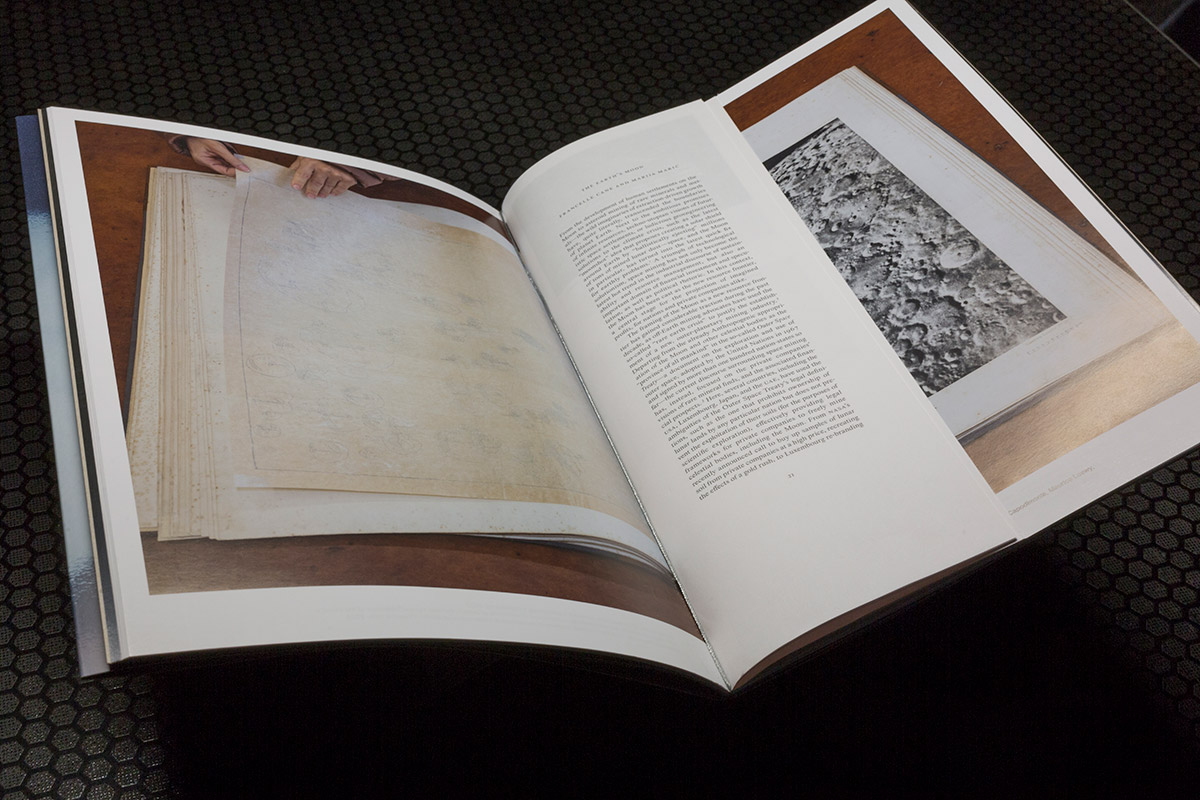

Down to Earth—Exhibition of the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, co-curated by Francelle Cane and Marija Marić

From the development of human settlements on the Moon to the mining of asteroid for rare minerals and metals—the wild imaginaries of extraction-driven growth have, quite literally, transcended the boundaries of Earth. This shifting of resource exploitation from the exhausted Earth to its 'invisible' hinterland—the Moon, celestial bodies, and ultimately, other planets—calls for an urgent debate on the impact this shift will have on our understanding of land, resources, and commons. Down to Earth critically unpacks the question of space mining through the perspective of resources, asking: how does this new iteration of the space race, wrapped in the false promises of endlessly available resources, depart from the existing extractivist logic of capitalism and its destructive environmental and social effects on the ground? How will the ongoing privatisation of space, characterised by a sharp turn towards private companies as main actors in the exploitation of space resources, affect the current status of extra-terrestrial bodies as a form of commons?

Designed as mock-ups of the Moon's landscapes, during the last couple of years, 'lunar laboratories' have emerged as a default feature of many of the institutions and private companies around the world, an infrastructure for the testing of different mining technologies. With the speculative economies of the space mining industry heavily relying on the staging of techno-fix narratives and resource fictions—it becomes clear that lunar laboratories go far beyond being facilities meant solely for testing space mining technologies, instead taking the role of media studios for the production of imagery of human technologies on the Moon. The exhibition of Luxembourg Pavilion takes 'lunar laboratory'—usually operating as a stage for performance of extraction—turning it into a backstage for the critical unpacking of the tech industry's dreams of financial growth, thus also offering another way of seeing the Moon: that which goes beyond the current optics of the Anthropocene.

The exhibition features three different projects developed throughout the course of the research—a film, a workshop, and a publication. Titled Cosmic Market, the film, developed in collaboration with Armin Linke, exposes connections between scientific research and differing interpretations of space legislation, as well as between technological development and the establishment of a new market, both on Earth and beyond. A collaboration between the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) and the Luxembourg Pavilion, the workshop how to: mind the moon started from the research on five lunar materials, outlining another kind of material library, that which goes beyond the perceived scientific neutrality of materials science. The workshop, co-curated with Lev Bratishenko, features contributions by: Jane Mah Hutton, Anastasia Kubrak, Amelyn Ng, Bethany Rigby, and Fred Scharmen. And finally, published by Spector Books and designed by OK-RM, the publication Staging the Moon: Resource Extraction Beyond Earth collects essays and fragments of research on questions of resources, legal framing of lunar soil and commons, as well as the infrastructural power of the New Space Age media in legitimizing mineral extraction.

Project 2

Real Estate Poetry

Real Estate Poetry—currently being developed as a book. Here is a short excerpt of texts introducing into the project: Could texts on architecture, written to sell, be considered as a new and unexpected sources of fiction and poetry?

Real Estate Poetry is an outline for a new literary genre, one that is solely based on real estate advertisements. Ads, seen as ephemeral texts soon to be obsolete after the product is sold, are collected and transcribed, displaced as ready-mades and reread as literary works of poetry.

Instead of adding images for this project, I will add two real estate poems: (1) Live, Work and Play, published in 2019 as part of Avery Shorts Season 3 series, which collects text excerpts from 34 different 'live, work, and play' real estate developments around the world, and (2) Housing for a Lonely Generation, originally prepared for 2020 AHRA Housing and the City Conference and forthcoming for publication in Footprint 32, based on the advertising language of differen corporate co-living platforms (WeLive, Collective, Quarters). Both poems (like all other pieces of real estate poetry) are made solely by reassembling advertising language and do not involve new writing.

Live, Work and Play

Live, Work and Play

Marija Marić

to live, work and play in

to live, work and play

to live, work, and play

to live, work and play in

we work, live and play

they live, work and play

for you to live, sleep, work, and play

your work-live-play life

can live, work and play

can work, live, play—and relax

will live, work and play

vibrant live-work-play environment

ultimate live-work-play experience

the live-work-play-learn township

Live. Work. Play. Narrative

Live. Work. Play.

Live-Work-Play

Live, Shop, Work, Play

Live, Learn, Work, Play

Live, Play & Chill

to live, work and play

Work, play and stay

eat, meet and play

Come in, stay, play, enjoy

integrated live-work-play business

the ultimate live, work, play lifestyle

the live, work, play taken care of

place to love, work and socialize with

to live, work, play, relax and stay

to live and work, dream and play

to love, work and play

to Live, Work and Play

contemporary life, work and play

urban live-work-play lifestyle

Lock and leave with peace of mind,

Or stay and work and play.

Housing for a Lonely Generation

Housing for a Lonely Generation

Marija Marić

The new way of living is inhabiting time, space and place that stirs inspiration inside of us.

Join the global living movement.

Find your people.

Join us.

Imagine a place where you enter as an ‘I’ but leave as a ‘we’.

Connect in spaces designed to bring incredible people together.

Meet neighbours and make new friends.

Be more together.

We are:

Allergic to the unoriginal.

Unbound by convention.

Opposed to the 9 to 5.

Inspired by independence.

Open to adventure.

And firm believers that we’re only as good as the people with whom we surround ourselves.

Network with freelancers.

Brainstorm with entrepeneurs.

Share skills and find solutions.

Our community might just contain your next friend, lover or menthor.

#wecommunity.

Grab a coffee fix to kickstart your day.

Perfect your presentation in the co-working space.

Now book the boardroom and nail that pitch.

Live it up.

Stress less.

Gather. Stretch. Steam.

Caffeinate. Co-work. Present.

Meet. Mingle. Collaborate.

Watch. Learn. Create.

Chop. Chat. Unwind.

It feels like home. Maybe even better.

This is home. It’s your home, your workplace and your playground.

A home to share with friends, teachers, chefs, engineers, artists and yourself.

Stay or live.

Take a break and connect with those around you over lunch.

Join the wine society in the restaurant for a tasting, then prepare a feast with friends in one of the shared kitchens.

Living with passionate, inspiring, positive people who are excited and open to discovering the world.

Game-changing convenience in one all-inclusive bill.

Hello. We are co-living.

We’re the world’s largest co-living provider.

Yes, that’s big.

Building real-estate of the future.

Property and software under one roof.

The Good Life.

Website: marijamaric.xyz

Instagram: @zdravo.marija

Photo Credits: ©Antoine Espinasseau, Portrait Image: ©Teodora Ivkov

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 10/2023