23/004

Matthew Crabbe

Researcher and Teacher

Natural Building Lab, TU Berlin

«It is important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.»

«It is important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.»

«It is important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.»

«It is important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.»

«It is important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.»

Please, introduce yourself…

I am Matt, and I am part of Natural Building Lab at the TU Berlin, where I am teaching, researching and practicing as well as working on my PhD “Change Now, Architecture Later!”. That is probably the official job description – in reality, this also includes a large portion of organising, enabling, improvising and daily logistical problem solving – transporting heavy objects with cargo bikes, securing things with tension belts and trying to keep the batteries charged and the keys in the right place.

Portrait Matthew Crabbe

How did you find your way into the field of architecture and later the extended field of architecture you are working in now?

Honestly, I am not sure – it is not something that runs in the family. I think somebody suggested it to me growing up, and it stuck. I was always interested in graphics and photography at school and ended up studying for my bachelor’s in architecture at Newcastle University in the UK. By the end of my bachelor, I still only had the barest understanding of what the job was or could be. I certainly had not formulated a personal position in relation to any of it.

In 2011, I moved to Berlin for an internship with ZRS Architekten and started working with Eike Roswag-Klinge. I didn’t speak German at this point, so I went to language school every evening for the best part of nine months. One of my first memories with Eike is taking some measurements on a site, he gave me a Zollstock, and I remember thinking: what am I supposed to do with this weird stick? I initially planned to stay for six months and then apply for a master’s program in London. In the end, I worked for three years at ZRS between bachelor/master and spent some time working on conservation projects abroad, which gave me some hands-on experience and the chance to do some travelling. In 2013 I spent a month with the Tibert Heritage Fund in Leh (India) restoring earthen houses. I eventually had a place for the master’s in London but chose not to accept it because, by that time, Berlin was starting to feel like home, and my German was good enough to apply for the master at the TU Berlin.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project?

The master’s was a significant phase for me. I was still working on a student basis with ZRS during my studies. I didn’t know the TU Berlin context, so it was a lot of new things for me. The first studio I did was a Hochbau Studio; I remember everybody meticulously casting stuff out of gypsum and cement; I had never seen that before – I didn’t realise until later that this was a bit of an architecture student convention. In that studio, it was more about space than programme, construction or user. I think by having one foot in practice, it was tough for me to adjust to that kind of abstract approach, and it was not something that I could initially identify with. After that, I did two urbanistic studios and found that approach interesting, one with the Habitat Unit, where I first got some idea of what being a “researcher” in architecture could mean.

My thesis also came by way of ZRS, where a German NGO approached us with a project partner in Karnataka in India, who had raised funds to build a school for disabled children and were interested in using local materials like earth and bamboo. I spent a month on my own in Karnataka with the local partner doing research and workshops. I spent a lot of that time using some approaches I had learned in different studios, such as mapping, photography, interviews and workshop formats to gather information. I also was really questioning myself, my motivations and the basic premise of the whole project.

Once I had presented my thesis, the conversations turned to the realisation of the project. I was then working full-time; I couldn’t imagine doing the whole project in my free time, so we calculated the absolute minimum fee we would need for the rest of the planning and construction with ZRS. I remember speaking to the NGO on the phone and just having to say: you know what, I would recommend that you hire a local architect and do the project that way because it makes no sense to give so much of your donation funds to a German office to plan a school in rural India.

The discourse surrounding DesignBuild has moved on a long way since 2016, and the PhD dissertation from my colleague Nina Pawlicki “Agency in DesignBuild” (2020), does a lot to unpack some of the complexity of the debate surrounding DesignBuild projects, which is by no means black and white. That whole experience was a real turning point; in the end, I am not sure if the school ever ended up being built – if so, it was probably a concrete box. Would it have been better the other way? Moreover, for whom would it have been better the other way? I am not sure, but I learned a lot during that time.

Today you are part of Natural Building Lab. What is it and how did you get there?

After two years of working full-time, I became quite frustrated with the office and needed a change. I had thought a bit about applying for a university job regardless of whether Eike would be moving to the university. I spent another four quite stressful months doing site supervision for a conservation project in Abu Dhabi for a change of scenery and approach; in the meantime, Eike and Nina started Natural Building Lab (NBL) in Autumn 2017. When I got back to Berlin at the start of 2018, there was a teaching position open; it felt like the right time for me, so I applied and was really happy to get the job.

Natural Building Lab is the Chair for Constructive Design & Climate Adaptive Architecture at the School of Architecture at TU Berlin. We started small but have grown with research projects over the last 18 months. Currently, our team is about 15 people.

Our key expertise is natural building materials and life-cycle construction. These are the themes and materials of the future. Since we started, we have seen students making much clearer demands from the institute to put these themes at the centre of their studies. We don’t need a reinforced concrete ban for our studios because the students don’t want to design concrete buildings. It is not about us setting rules or telling people what to do, just opening up a space for people to put the themes that are important to them in the centre of their projects. We have been doing a popular open lecture format called NBL Grundlagen (check the homepage for new dates) since 2018, where we cover themes such as timber & earth construction or life-cycle building for anybody interested and it is fantastic to see how many students from other disciplines or other universities are tuning in to hear them.

Besides materials, we have developed a particular approach and identity in our teaching over the last nearly five years. Our design studios nearly always have a real project context and involve working with real actors on real problems. We also try to bring the studio’s outcomes into reality, either in the form of DesignBuild projects with a construction phase or through exhibitions or performative presentations with project partners and non-experts.

The studio should be a place to learn collaboration, not a competition and the outcomes of the semester should belong to the entire collective rather than the individual. This means our studios often produce some extremely tight-knit collectives who carry on working together after the semester, and the projects often spill over into spin-off projects that span multiple semesters and formats. We usually start the semester with a critical-mass bike tour of the places we will be working in the different studios – in winter, this is usually about 75 people, so we usually have some more or less productive discussions with the Berliner Polizei.

Selection of Projects, Natural Building Lab

What does your desk/working space look like?

My working space varies enormously depending on what is going on. Last winter semester, I was spending at least two days a week in the Wilma Mall in Charlottenburg (more on that later), one in Potsdam and the rest spread across home-office, the Fachgebiet and the workshop. I don’t even come to the office with the idea of having a concentrated and productive day anymore; there is always too much else going on, the socialising is also very important! If I want to be concentrated, I will stay at home or in Thüringen as part of Haus Döschnitz e.V.

I did attach a few candid photos from our TU Institute for Architecture office – it is a concrete monster with a special place in our hearts! We softened it by putting earth plaster on the walls and hoped that the late Bernhard Hermkes could understand the positive side of this (reversible) intervention.

Working Space – Natural Building Lab, TU Berlin

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

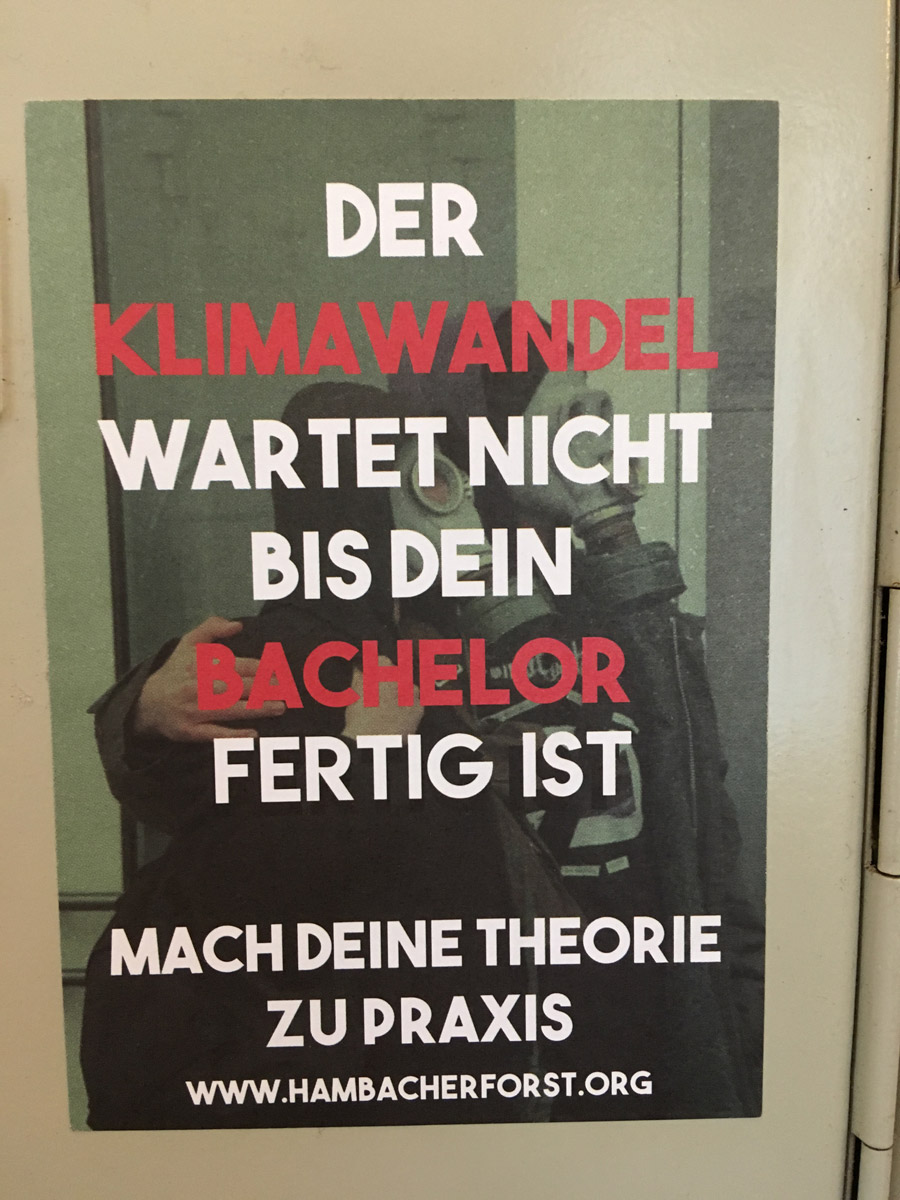

For me, the essence of architecture is getting things done as a collective – I have a photo of a sticker that I saw in a climbing gym in Leipzig that reads: “the climate emergency will not wait until your bachelor is finished”. I love that photo! From the outside, I always thought a university job is all about design tutorials and reading ARCH+.

Sticker – Climbing Gym – Leipzig

In reality, especially with the kind of projects and collaborations we are involved with, it is more like 20% content and 80% organisation – every semester, we have a new team, new partners and new contexts – we are constantly trying to enable things, to keep things moving forwards and this requires good collective organisation and decision making. I think this mirrors a lot of what is necessary in practice – yes, good design is hugely important. We need good designers, but if you want to enjoy the trust and belief required to push through a radical environmental agenda on a serious building project, you need to be exceptionally well-organised, collaboratively minded, and an excellent communicator. This starts in the design studio. We aim always to make ourselves as teaching staff surplus to requirements and to focus on what we can learn from the people we work with, not what they can learn from us. I think it is really important to practice communicating what we do with people from different disciplines and backgrounds.

Name your favourite …

Book/Magazine: Awan, N., T. Schneider, and J. Till. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Taylor & Francis, 2013.

Tool: Japanese Saw – also handy for bread

Studio Format: Speed Dating – great for learning to get to the point quickly

Short Note on Speed Dating: We have done a few different versions of this. It works best with a second studio or group, who are the potential collaboration partner for the semester. We did this last winter with a group from the Uni Kassel, who were also working on the same studio project. Credit for the excellent NBL speed dating assessment form goes to my colleague Selina Schlez! Basically, you have a series of five-minute speed dates to really quickly find out if you have the same expectations/vision for the semester. We had little paper slips to fill out with categories (things in common, expectations, content and match potential) and you got the feedback slips from your dates back at the end. You could say: at least everybody had a good laugh and got talking to each other. You could not really say: fruitful long-term collaborations emerged from the process.

Best way to make groups: Emoji Blind Dates

Short note on Emoji Blind Dates: This was a pandemic invention. Finding groups for the first task, when everybody doesn’t know each other, is always a bit tricky. Everybody has to write a little “about me” in advance and chooses an emoji that they feel a strong connection with. We then make blind dates based on the compatibility of the emojis. Instant talking point and great group work guaranteed.

Animal: Donkey – uncomplaining logistic partner with pretty eyes

Machine: MiScreen – an absolute game-changer for our screen printing side projects

Building material: Earth – a pleasure to work with and full of potential for the future

Snack: Peanuts – I don’t know what I would do without peanuts

Emoji: :whale: – Pure happiness

How do you understand the relation of research, practice and teaching in architecture?

This is something that I am thinking about a lot in connection with my PhD. The three aspects or roles – researcher, learner, and practitioner – are intertwined. We are fortunate at the TU Berlin to have highly motivated and engaged students from all over Germany and beyond, and these are the people who will be pushing the discourse very soon. I think we all need to work on themes simultaneously from different perspectives to respond to the sheer urgency of the challenges facing us.

As teachers/learners, we have to think about what the job will be like in ten years rather than ten years ago. For instance, I wonder how many of the next generation will even have the privilege to build new buildings with new resources – so why so much focus on new construction in architecture school? Who will be able to afford to build with reinforced concrete in 10 years – so why spend so much time in Bachelor talking about concrete and gypsum drywalls? We are also practitioners, and we want to be out there with our projects on the ground with real people making a real contribution by bringing new knowledge, innovation and approaches into reality through pilot projects, prototypes and processes. Being a researcher is, for me, about reflection and looking at ways to understand, document and improve our practice.

I am interested in practice-based research approaches, which allow me to make my creative practice as a teacher a valid form of research for my thesis, that can be interrogated and challenged. I hear a lot from students who don’t think they can work “academically or scientifically”. The research landscape in our field is, like so many other things, in transformation, and the change is towards approaches that can bring practice and research much closer together. It took me a long time to find a position in a hugely complex and somewhat intimidating field, but it is a really exciting time to be a researcher.

That said, there are some serious structural and administrative problems in the German university system that make it extremely difficult to achieve any long-term job security – only the fewest people will make it to a professorship, and the majority of these people remain to come from practice, rather than an academic background. I would like to see more requirements for people with a professorship to be held to account to feedback from their colleagues and students rather than being offered a life-long position with no incentive to innovate. At the TU, we are somewhat in the middle of a long overdue generation change, and the institute is slowly moving in a positive and more diverse direction. Fingers Crossed…

What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

I found this question difficult. It conjures images of architects making the world a better place by designing pretty buildings or being an “amateur generalist”. I think this illusion is pretty much put to bed. I find it hard to generalise what architecture and architects have to contribute to society. We are living through a dilution and divergence of traditional job descriptions across all sectors and architecture is also part of this transformation.

Last week we had master thesis presentations. Afterwards I was talking to the mother of one of our graduates who said something like: “you need an extra description to explain what they are going to do – architect comma something”. I think that kind of sums it up, architecture is such a broad description, and I think it will only become more diverse. There is space for different approaches and specialisations, all of which will have something different to contribute to society. There is no longer a clear job description, and I think we have a responsibility to push these diverse approaches and ensure that graduates can apply situated knowledge, skills and values to different settings and problems during their careers.

What important actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

We cannot underestimate the size of the challenges we face in reaching that sustainable future; the problems are complex and often involve factors outside our control. Staying determined and motivated in the face of these challenges is hugely important. This makes it all the more important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.

As far as the political factors go – the Bauwende is not going to happen by itself; it is going to require legislation. On the one hand, I support many of the things being pushed by architect groups at the moment, such as the Abriss Moratorium, the Muster(UM)bauordnung and the work being done by Bauhaus Earth – on the other hand, I worry about the amount of time we loose with our internal discussions. Last week I was at the BDA Hochschultag in Berlin; the topic of discussion was how we can find space for “new themes” in university curriculums and whether there is a “sustainable aesthetic”. What could we have talked about with 150 highly influential professors if we did not waste our time discussing things that should have been clear five or even ten years ago?

I often wonder whether much of our discourse inside the architecture bubble can cut through to other spheres, such as politics. We need to concentrate on learning to communicate well with other disciplines and non-experts to think about what an expanded notion of design can mean in times of crisis and transformation – one book that inspired me on this is Ezio Manzini’s “Design When Everybody Designs” (2015 MIT Press). More than anything, we need to let go of our egos and make space for the next generation.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

Keep your ego in check, listen to people carefully, get outside of your bubble, manage your work/life balance, learn from your failures, reflect on your motivation (this was a perfect opportunity to do that), produce sweet screen-printed collective clothing and lastly, stay hydrated.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

Team Dis+Ko, Berlin

public works, London

morgen., Hamburg

Guerilla Architects, Berlin

Urbane Praxis, Berlin

In reality, especially with the kind of projects and collaborations we are involved with, it is more like 20% content and 80% organisation – every semester, we have a new team, new partners and new contexts – we are constantly trying to enable things, to keep things moving forwards and this requires good collective organisation and decision making. I think this mirrors a lot of what is necessary in practice – yes, good design is hugely important. We need good designers, but if you want to enjoy the trust and belief required to push through a radical environmental agenda on a serious building project, you need to be exceptionally well-organised, collaboratively minded, and an excellent communicator. This starts in the design studio. We aim always to make ourselves as teaching staff surplus to requirements and to focus on what we can learn from the people we work with, not what they can learn from us. I think it is really important to practice communicating what we do with people from different disciplines and backgrounds.

Name your favourite …

Book/Magazine: Awan, N., T. Schneider, and J. Till. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Taylor & Francis, 2013.

Tool: Japanese Saw – also handy for bread

Studio Format: Speed Dating – great for learning to get to the point quickly

Short Note on Speed Dating: We have done a few different versions of this. It works best with a second studio or group, who are the potential collaboration partner for the semester. We did this last winter with a group from the Uni Kassel, who were also working on the same studio project. Credit for the excellent NBL speed dating assessment form goes to my colleague Selina Schlez! Basically, you have a series of five-minute speed dates to really quickly find out if you have the same expectations/vision for the semester. We had little paper slips to fill out with categories (things in common, expectations, content and match potential) and you got the feedback slips from your dates back at the end. You could say: at least everybody had a good laugh and got talking to each other. You could not really say: fruitful long-term collaborations emerged from the process.

Best way to make groups: Emoji Blind Dates

Short note on Emoji Blind Dates: This was a pandemic invention. Finding groups for the first task, when everybody doesn’t know each other, is always a bit tricky. Everybody has to write a little “about me” in advance and chooses an emoji that they feel a strong connection with. We then make blind dates based on the compatibility of the emojis. Instant talking point and great group work guaranteed.

Animal: Donkey – uncomplaining logistic partner with pretty eyes

Machine: MiScreen – an absolute game-changer for our screen printing side projects

Building material: Earth – a pleasure to work with and full of potential for the future

Snack: Peanuts – I don’t know what I would do without peanuts

Emoji: :whale: – Pure happiness

How do you understand the relation of research, practice and teaching in architecture?

This is something that I am thinking about a lot in connection with my PhD. The three aspects or roles – researcher, learner, and practitioner – are intertwined. We are fortunate at the TU Berlin to have highly motivated and engaged students from all over Germany and beyond, and these are the people who will be pushing the discourse very soon. I think we all need to work on themes simultaneously from different perspectives to respond to the sheer urgency of the challenges facing us.

As teachers/learners, we have to think about what the job will be like in ten years rather than ten years ago. For instance, I wonder how many of the next generation will even have the privilege to build new buildings with new resources – so why so much focus on new construction in architecture school? Who will be able to afford to build with reinforced concrete in 10 years – so why spend so much time in Bachelor talking about concrete and gypsum drywalls? We are also practitioners, and we want to be out there with our projects on the ground with real people making a real contribution by bringing new knowledge, innovation and approaches into reality through pilot projects, prototypes and processes. Being a researcher is, for me, about reflection and looking at ways to understand, document and improve our practice.

I am interested in practice-based research approaches, which allow me to make my creative practice as a teacher a valid form of research for my thesis, that can be interrogated and challenged. I hear a lot from students who don’t think they can work “academically or scientifically”. The research landscape in our field is, like so many other things, in transformation, and the change is towards approaches that can bring practice and research much closer together. It took me a long time to find a position in a hugely complex and somewhat intimidating field, but it is a really exciting time to be a researcher.

That said, there are some serious structural and administrative problems in the German university system that make it extremely difficult to achieve any long-term job security – only the fewest people will make it to a professorship, and the majority of these people remain to come from practice, rather than an academic background. I would like to see more requirements for people with a professorship to be held to account to feedback from their colleagues and students rather than being offered a life-long position with no incentive to innovate. At the TU, we are somewhat in the middle of a long overdue generation change, and the institute is slowly moving in a positive and more diverse direction. Fingers Crossed…

What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

I found this question difficult. It conjures images of architects making the world a better place by designing pretty buildings or being an “amateur generalist”. I think this illusion is pretty much put to bed. I find it hard to generalise what architecture and architects have to contribute to society. We are living through a dilution and divergence of traditional job descriptions across all sectors and architecture is also part of this transformation.

Last week we had master thesis presentations. Afterwards I was talking to the mother of one of our graduates who said something like: “you need an extra description to explain what they are going to do – architect comma something”. I think that kind of sums it up, architecture is such a broad description, and I think it will only become more diverse. There is space for different approaches and specialisations, all of which will have something different to contribute to society. There is no longer a clear job description, and I think we have a responsibility to push these diverse approaches and ensure that graduates can apply situated knowledge, skills and values to different settings and problems during their careers.

What important actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

We cannot underestimate the size of the challenges we face in reaching that sustainable future; the problems are complex and often involve factors outside our control. Staying determined and motivated in the face of these challenges is hugely important. This makes it all the more important to bring things into reality – it is not enough to just have good ideas; they need to be actionable.

As far as the political factors go – the Bauwende is not going to happen by itself; it is going to require legislation. On the one hand, I support many of the things being pushed by architect groups at the moment, such as the Abriss Moratorium, the Muster(UM)bauordnung and the work being done by Bauhaus Earth – on the other hand, I worry about the amount of time we loose with our internal discussions. Last week I was at the BDA Hochschultag in Berlin; the topic of discussion was how we can find space for “new themes” in university curriculums and whether there is a “sustainable aesthetic”. What could we have talked about with 150 highly influential professors if we did not waste our time discussing things that should have been clear five or even ten years ago?

I often wonder whether much of our discourse inside the architecture bubble can cut through to other spheres, such as politics. We need to concentrate on learning to communicate well with other disciplines and non-experts to think about what an expanded notion of design can mean in times of crisis and transformation – one book that inspired me on this is Ezio Manzini’s “Design When Everybody Designs” (2015 MIT Press). More than anything, we need to let go of our egos and make space for the next generation.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

Keep your ego in check, listen to people carefully, get outside of your bubble, manage your work/life balance, learn from your failures, reflect on your motivation (this was a perfect opportunity to do that), produce sweet screen-printed collective clothing and lastly, stay hydrated.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

Team Dis+Ko, Berlin

public works, London

morgen., Hamburg

Guerilla Architects, Berlin

Urbane Praxis, Berlin

Project 1

Mall Anders

Mall Anders was a project we initiated with transdisciplinarity researcher Thorsten Philipp and the Berlin University Alliance. As I said above, we are always interested in getting outside of the uni/architecture bubble; in that respect, Mall Anders was a perfect opportunity for us to do just that.

Wilma Shoppen is a prominent shopping centre in Charlottenburg. Due to changes in the way we consume and the lasting effects of the pandemic, many of the malls in Berlin have big problems with vacant units – this is not helped by the massive excess of malls in Berlin. For six months last winter semester, we were able to transform an empty unit into an open learning laboratory, where different groups and initiatives from the Berlin Universities and civil society could experiment with new learning and communication formats in the form of events, talks, exhibitions, performances and workshops. The aim was to contact people who would not usually come onto the university campus and see what new forms of exchange and knowledge production this would enable.

We transformed the space in six weeks with 15 participants from different disciplines, starting with just the idea that we needed a flexible spatial infrastructure that would be able to accommodate the maximum variety of different formats and arrangements. We used the shop infrastructure left-over by the last tenant to create different elements like a mobile kitchen, exhibition walls and a multimedia tower. We aimed to return as much of the infrastructure as possible to the original shop configuration at the end of the project – I think the unit is now Zara Home...

We were lucky enough to cooperate with Silvia Gioberti, Nike Kraft and Leon Klaßen from Guerilla Architects in the seminar, bringing some great new impulses. We talked a lot about what our role was doing a project in a shopping centre and what we were or were not supporting even by being there. Some of the things we did with the seminar after the opening in December: we got to know our neighbours through speed dating, hosted a fashion show, played table tennis on the shopping street and planned a performative programme for a week in January – Sleep No Mall. We had a 24-hour presence in the shop for three days and a different performance every day.

One day, we wore our matching red Mall Anders uniforms and walked circuits around the mall for one hour. On another day, we placed pairs of chairs all through the mall and then sat down for one hour and read a book out loud. One thing you learn from spending a lot of time in a shopping mall is that it is very, very loud and very, very bright. After three months, I began to see what the hype for the noise-cancelling headphones is about.

If you would like to hear some more about the project, there is a really fun podcast from THF Radio, which was recorded with us during Sleep No Mall. It was not only a great semester for improvisation and self-organisation but also a practice in communicating your intentions and motivations to passers-by and visitors.

Project 2

Re:chenzentrum

The future of Rechenzentrum (RZ) in Potsdam city-centre has been the subject of controversial debate for a number of years. An example of DDR post-war modernism, the building was constructed in 1961 and used as a data-processing centre. By 2015 only one floor was in permanent use and an agreement was reached with the city administration for temporary usage of RZ as an art and creative centre. Since then, it has become one of the most important centres for socio-cultural and civil-society creative practice in Potsdam. However, this agreement has always been under threat by the planned demolition of RZ to accommodate the reconstruction of the highly controversial Garnisonskirche.

Last summer we were invited by the RZ for a talk as part of their „FÜR …. Bauen im Bestand“ and got talking about the project, they are a super engaged and activist team and we obviously couldn’t resist getting involved. The idea of the studio Re:chenzentrum was to develop together with 20 masters students and the users from RZ, visions for the transformation of Rechenzentrum that could contribute to the political and public debate. We were really lucky to be able to use a studio space in RZ, so we were in Potsdam “on-location” every Friday using the building and getting feedback on ideas. We started out with a free format mapping task as a way into the complex urban-political debates and history of the project as well as trying to understand better the way the existing building functions and the social and material resources it contains. After that we worked in four groups of about five people, the aim was always to produce projects that complimented each other and showed the different directions that a transformation could go in. We also had one group that followed a more activist performative direction through public-space interventions and events.

Every step of the way we had very productive discussions and feedback from the team in RZ so that the projects remained grounded in the needs of the building’s users. I think rather than stifling the creativity of the students, this gave the projects a relationship to a real context that means they cannot be dismissed going forward. They present a radical vision of how much is possible within the constraints of an existing building. At the beginning of the studio, we decided as a group that we would not investigate anything except a complete 100% preservation of the building – this in itself was a radical statement considering the state of the debate at that time. Throughout the winter, more scandals relating to the finances of the Stiftung Garnisonskirche came out in the press. This meant that the second building phase, which would theoretically mean at least a partial demolition, is on ice – for the time being.

At the end of the semester, we exhibited the projects in Rechenzentrum and gained quite a lot of publicity in the local press. The RZ team are well connected so we also had a number of representatives from the city administration and politicians including the mayor come to the exhibition as well as hosting workshops for the RZers themselves. The semester was a real success, yet it brought home the reality to us that groups like the Rechenzentrum have to fight tooth and nail for every millimetre of ground from the city administration, while the now officially fraudulent Stiftung Garnisonskirche are supported with millions of taxpayer euros. This is totally unrelated to the debate surrounding what it means to be demolishing occupied buildings in times of resource scarcity and climate crisis.

In any case, our collaboration with Rechenzentrum is ongoing and while one group continued to work together with RZ over the summer semester on a

website and documentation, we are going to use this semester to look in more detail at the costs of the different strategies and to try to reduce the three projects into one strategy document that the RZ Team can use in the upcoming discussions with the city administration. I hope that we can keep the cooperation going and that we will be talking about a real-world laboratory for the transformation of RZ very soon!

Website: matt-crabbe.de / nbl.berlin

Instagram: @natural_building_lab

Photo Credits: 211217_REZ_zwpres_Krisitina 6 (Kristina Tschesch) All other photos - © Matthew Crabbe, Natural Building Lab

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 03/2023