26/001

Mork-Ulnes

Architecture Studio

San Francisco/Oslo

«For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings.»

«For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings.»

«For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings.»

«For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings.»

«For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

We are a somewhat unusual studio: an international office of just 12 people spread across nearly opposite parts of the world. Founded in San Francisco in 2005 and Oslo in 2011, we are this month opening an office in Honolulu, spanning over 10,000 km and a 12-hour time difference. While our choice of office locations has been driven by pragmatic and personal reasons, the dialogue between these places has shaped our thinking. The contrast—California’s optimistic can-do spirit and Norway’s grounded pragmatism—remains central to our methodology, even as our work reaches well beyond these locations.

Our working approach is rooted in curiosity due to this background of working in different cultural landscapes. I’m Norwegian-born and have had the privilege of living in several countries and traveling extensively. This exposure has made me naturally inquisitive, and I hope that curiosity has become part of our studio’s DNA. We strive to understand the places we work in—environmental, economic, social, and cultural conditions—so our buildings emerge from their context, shaped by the specific qualities of each place.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? What comes to your mind, when you think back at your time learning about architecture?

I wasn’t the kind of architect who knew from age four—while playing with Legos—that this was my career path. I didn’t fully decide to become an architect until I was into my art studies at the California College of the Arts and Crafts.

My mother was a painter, inspiring me through her studio work, while my father, a diplomat from rural Norway, instilled a deep curiosity about culture and the world. Before college, at the age of 17, I spent a year traveling around the world, noticing how buildings and cities reflected their social, cultural, geographic, and economic contexts. Even before the digital age, these differences fascinated me, and I believe that diversity in architecture persists despite globalization.

It took decades to fully realize that my upbringing and travels shaped my desire to explore how architecture can reflect and define a place and its culture. But I am very cognizant of this now, even as I just travel from one neighborhood to the next.

What were your experiences founding your own office and being self-employed? Why did you start your own projects? What difficulties did you face?

I had considered starting my own practice for some time, but the real turning point came thanks to a close friend who believed I could do it and made the introductions that made it possible. David connected me with a large project that provided financial stability and gave me the confidence to take the leap. Being self-employed has always been, and still is, sometimes scary.

I feel a strong responsibility toward the team, not just financially, but also in maintaining the quality of our work. I feel a constant pressure to improve, to raise our standards, and that challenge is part of what keeps me engaged. Looking back, I realize I may have been a bit naive about the full weight of those responsibilities—like making sure everyone is paid and supporting my family.

The biggest benefit is the freedom it offers. I’ve never done well with authority — maybe shaped by a strict Italian kindergarten run by nuns — and I try to give the same sense of freedom to everyone on the team.

How do you remember your time as architectural employee/worker?

I have only fond memories of being an employee. I was fortunate to work for a kind and thoughtful mentor, Peter Pfau, who cared about creating a supportive environment for all of us. When I became an employer, I wanted to ensure the same—that everyone on the team feels valued, comfortable, and that we’re all in it together.

This attitude is maybe more Nordic than American. I strongly believe that architecture is a team sport, and I don’t care if it’s my idea or the interns that forms a project. The best idea should always win.

I hear a lot about negative working conditions in our field, and I’ve been lucky not to experience that. I see it as part of my responsibility to contribute to a positive, supportive environment in our office. I hope the team agrees.

Even though architects’ salaries are often low compared to the education and effort required, I have always believed our work as architects makes an important contribution to society. I still feel energized going to work every day as an architect, and I doubt I’d feel the same way in most other professions. I’ve never regretted being either an employee or an employer in the field of architecture.

Given your professional experience in both Norway and the U.S., how would you compare these locations for practicing architecture? How is the context of these specific places influencing your projects?

The way we work day to day differs between our offices, but the end result is the same—we produce buildings. Regulations, budgets, and norms vary since we’re at opposite ends of the world, but they don’t really define the projects. For examples, regulations are less strict in Norway than in California, so we might make stairway guardrails a bit more open. Budgets in the US are usually higher, which lets us explore more complex details. To me, these are just practical opportunities or constraints rather than what shapes the work.

In the end, we try to make all our projects feel consistent, following the same methodology and linear logic, so it’s really about what makes a project a “Mork Ulnes” project—whether it’s in Hawaii or the Norwegian Arctic.

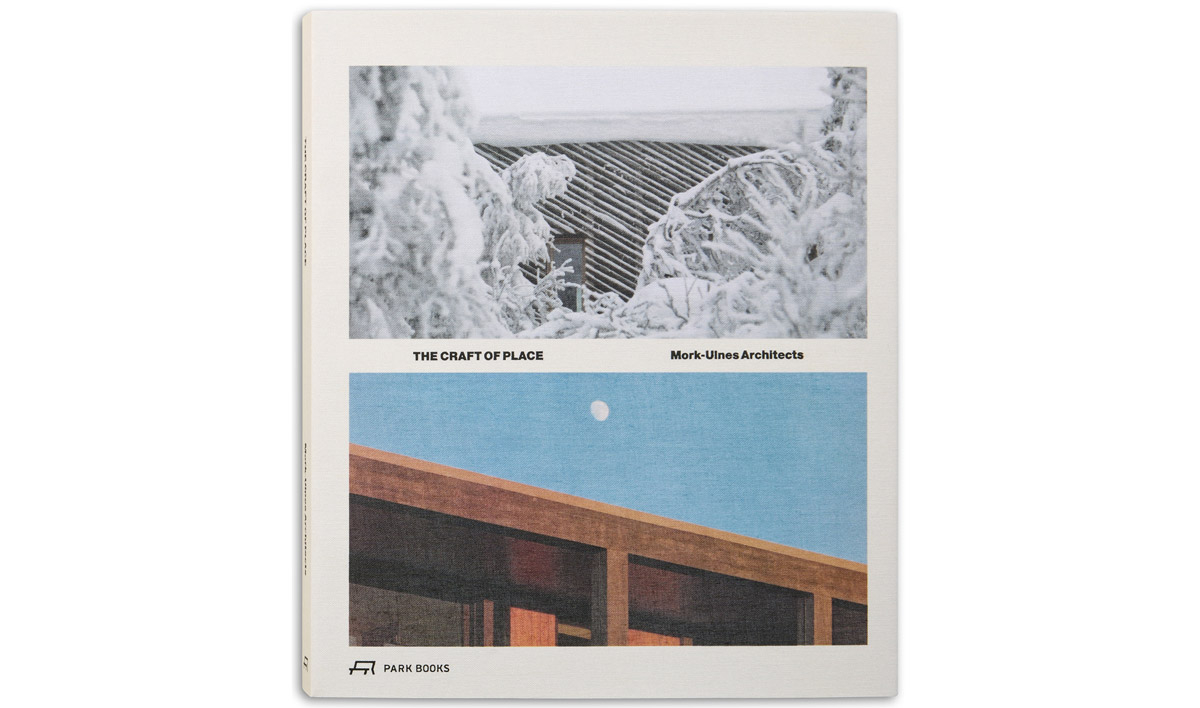

So location is everything in our work. We even spent two years writing a book on how Place shapes our projects. Over time, and with the opportunity to see more of the world, I have realized this is truer than ever. For us, location drives the project—it teaches us what a building wants to be, how it should function, and how it can respond to its surroundings. In our best projects, it informs everything from site strategy to minute details. While we are influenced by modernism and other -isms, place is always the foremost influence.

We go into much more detail in the book, so I’ll stop here.

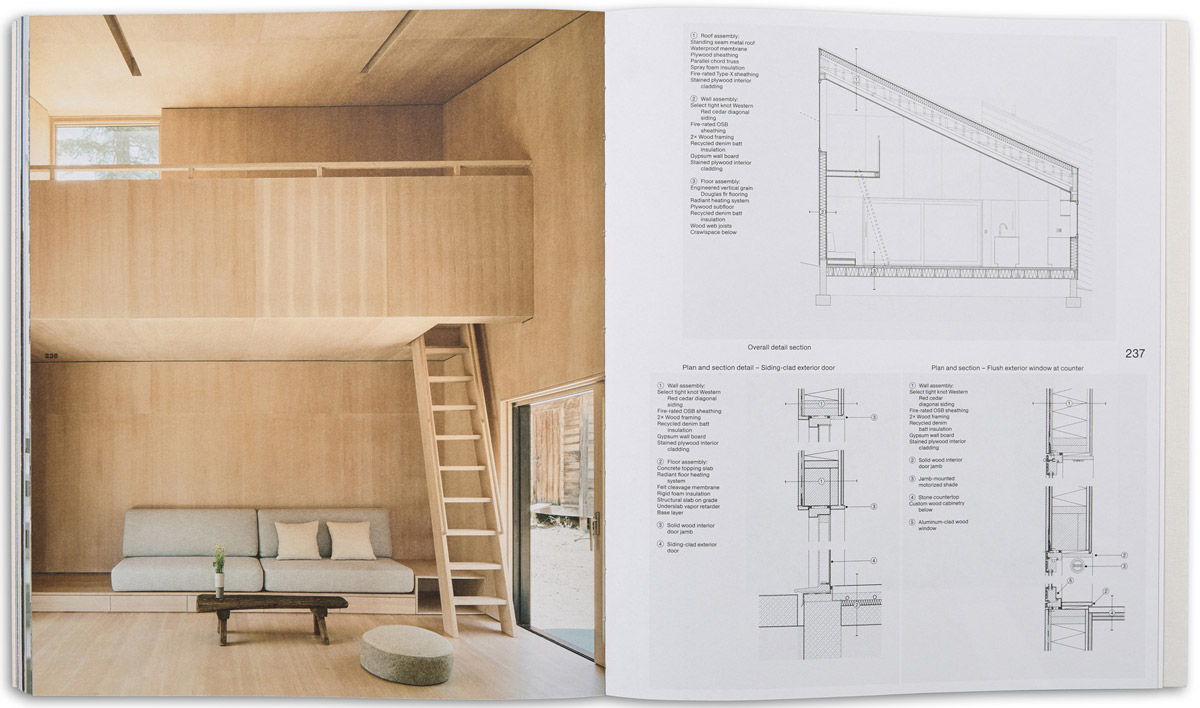

The Craft of Place – Mork-Ulnes Architects – Park Books

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

Even though I like things tidy, my desk is usually a bit messy. My desk probably looks like most other architects and is full of books, papers, sketches - and notes as reminders of what I have to do and remember.

Working Space – Casper Mork-Ulnes

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

Creating shelter that responds to its use, and most importantly its place on earth.

Name your favorite …

Book: Studies of Tectonic Culture by Kenneth Frampton, who taught the course I took at Columbia, introduced me to critical regionalism. Another is a relatively obscure book called Schirmer and His Students, documenting the work of architecture students in the late 1800’s. Gudbrandsdalen, where our family cabin is located, has an incredible building heritage, and the student drawings in that book are a lasting inspiration. We explore this in our own book.

Magazine: I read too many, but my subscription to Architectural Review is always at my bedside.

Building: I’ve been fascinated for decades by granaries. Wherever they are in the world. They are simple in function yet reflect a region’s specific craftsmanship, materials, and tectonic approach.

Mentor/Architect: Perhaps the farmers and fishermen who built durable, modest structures that still stand today in Norway—they embody practical knowledge and care in the landscape.

Material: Wood. No other material has the same sensory and structural qualities—tactile, olfactory, aesthetic, functional etc. And wood can be used almost everywhere in a buildings parts.

Spatial Memory: Not original, but the Pantheon. Its simplicity and the way it combines space and light with clarity.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

I hope there will be a time again when people care about quality and craft the way they used to, even just a hundred years ago—to build something that lasts. I don’t think it will happen, but it’s a utopian idea that one can strive for.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

First and foremost, I believe we should build for a lifespan of 100–200 years, not 20–30. This was once the standard mindset, but today, most construction is short-sighted—poorly built, with materials that don’t age well or retain beauty over time. Too often, quality architecture is reserved for the wealthy, while the majority of buildings are designed for quick use and disposal.

In the Nordic countries, there’s been a strong debate about working with the existing building stock. I don’t think that’s the only answer, but it could have the biggest short-term impact on sustainability. It wouldn’t surprise me if soon, demolishing buildings becomes illegal in Norway. Europe may lead in this regard, and I think it could have a transformative effect, as seen in projects like the Danish pavilion at this year’s Biennale.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Be analytical. Research and learn from the past, not just what’s considered cool at school today. This has become increasingly important to me as an architect. Don’t skip history classes or avoid the library just to focus on your studio design projects—there’s so much to learn from what’s been built before. What worked, what didn’t, and why.

Understanding the past can help you better grasp the context—how place, culture, and history shape a building. Perhaps most importantly, this encourages designing for the long term, something enduring, rather than creating a style of architecture that will quickly go out of fashion.

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

I’m perhaps a bit old-fashioned, but nothing beats as parti hand sketch to distill down a concept. Rhino models are great for iterating ideas quickly—but if I had to choose, I’d always start with the hand sketch to develop a concept.

Do you think AI is changing the field of architecture?

Too early to tell really. As mentioned, our design process is iterative, so maybe AI can help us make this process more efficient. But, I also think AI is daunting and I think I share the same concerns, other architects have.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

I tend to look both backwards and forwards. We probably reference older projects or architects more than new ones — not necessarily famous architects, but people who really understood their place and materials. For example, older farm or fishermen’s structures show how form, structure, and materials can respond to their particular locale and last for centuries. In combination, we also use modernist techniques in our work, so I, of course, look at earlier regionalist projects — from mid-century Californian architects to the 1970s San Francisco Bay Regionalists, and Nordic architects from the same era.

There are, of course, many smaller contemporary offices doing inspiring and thoughtful work that I reference. But for me, it’s less about a particular architect or style and more about work that demonstrates humility, longevity, and responsiveness. Often, I am again surprised that the most inspiring lessons can come from simple, even overlooked, buildings that we stumble upon in our research.

Project 1

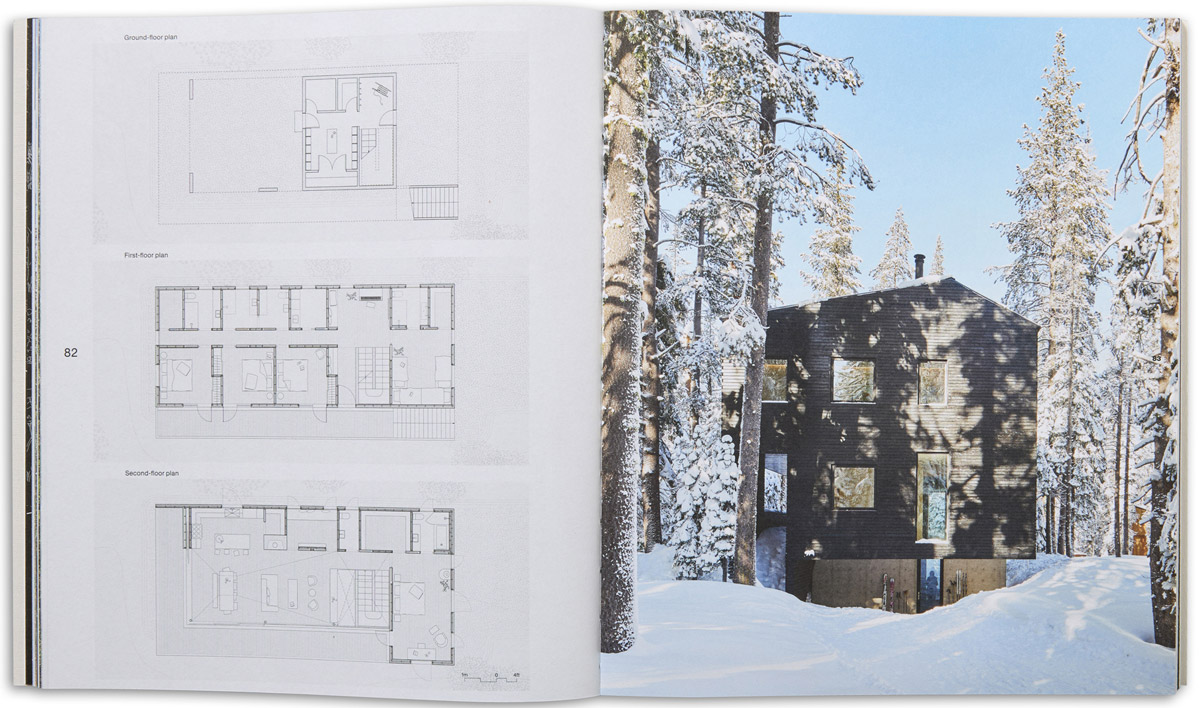

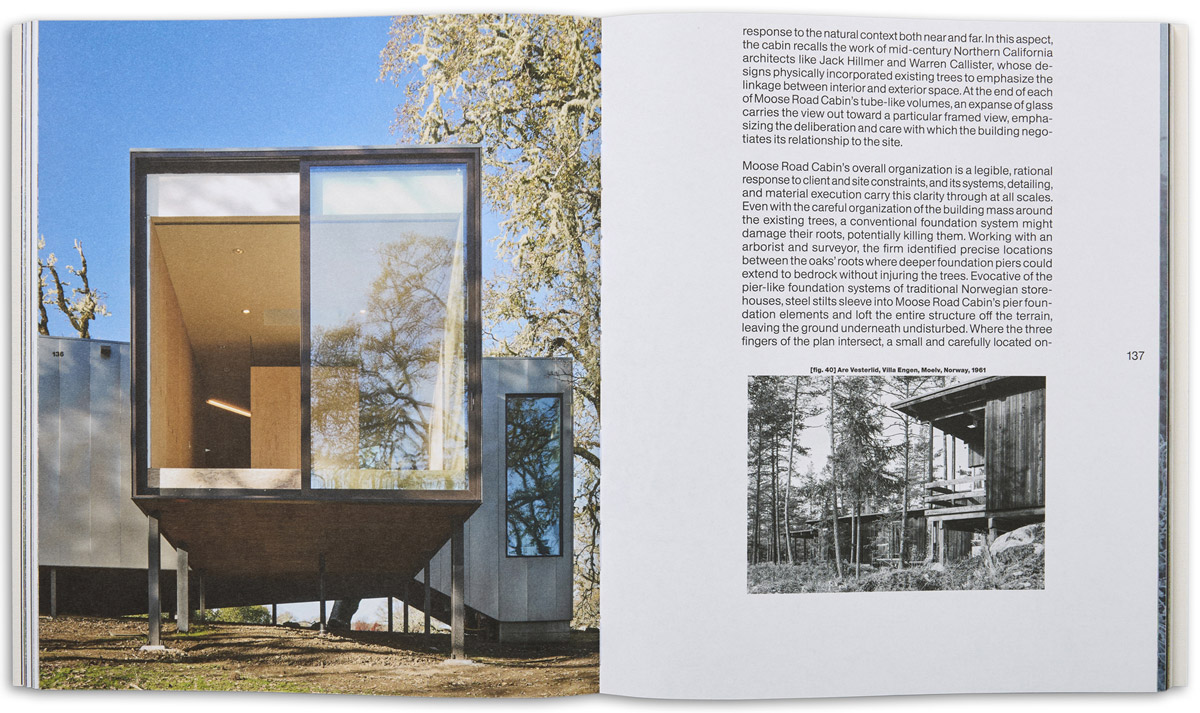

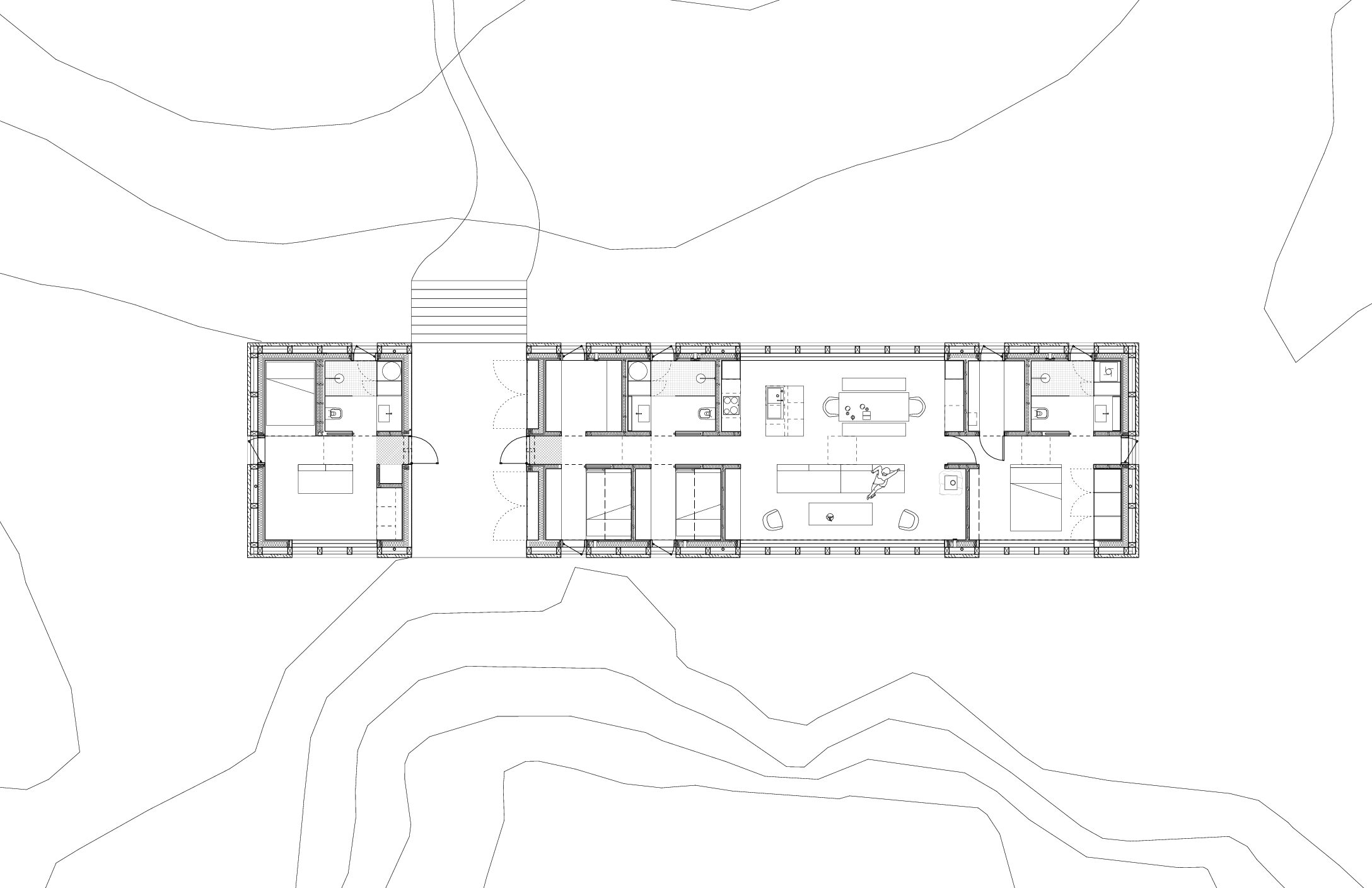

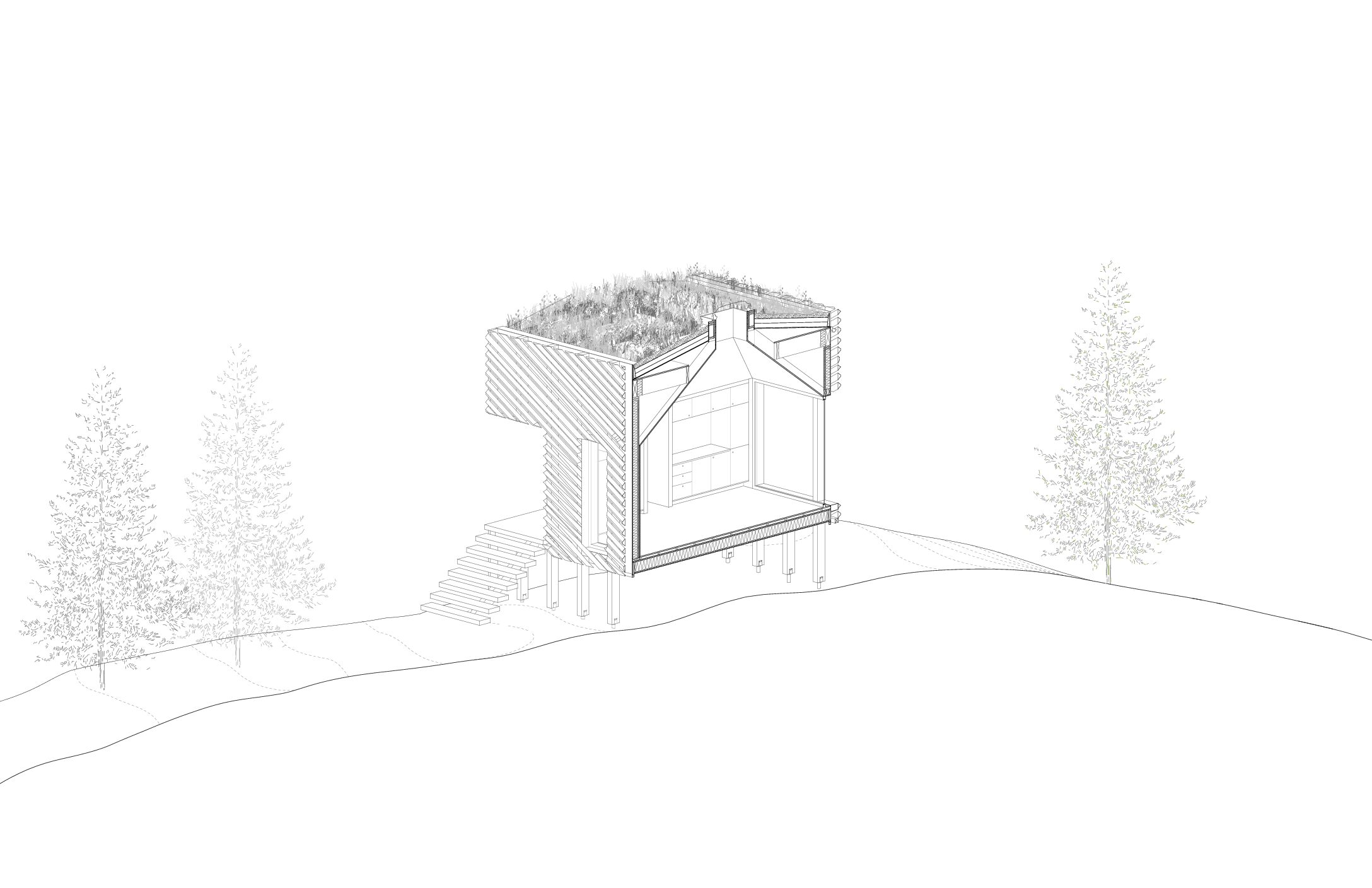

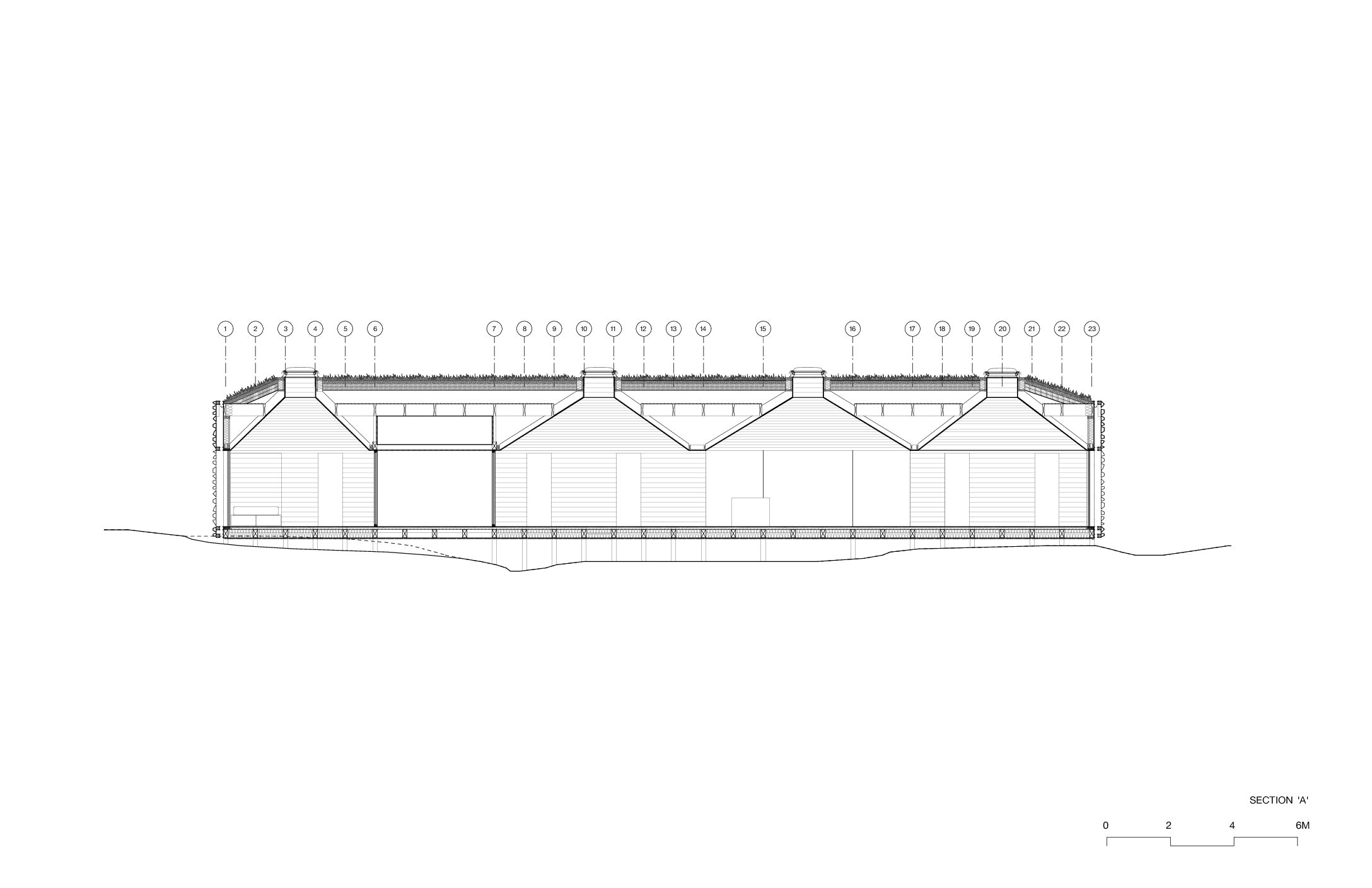

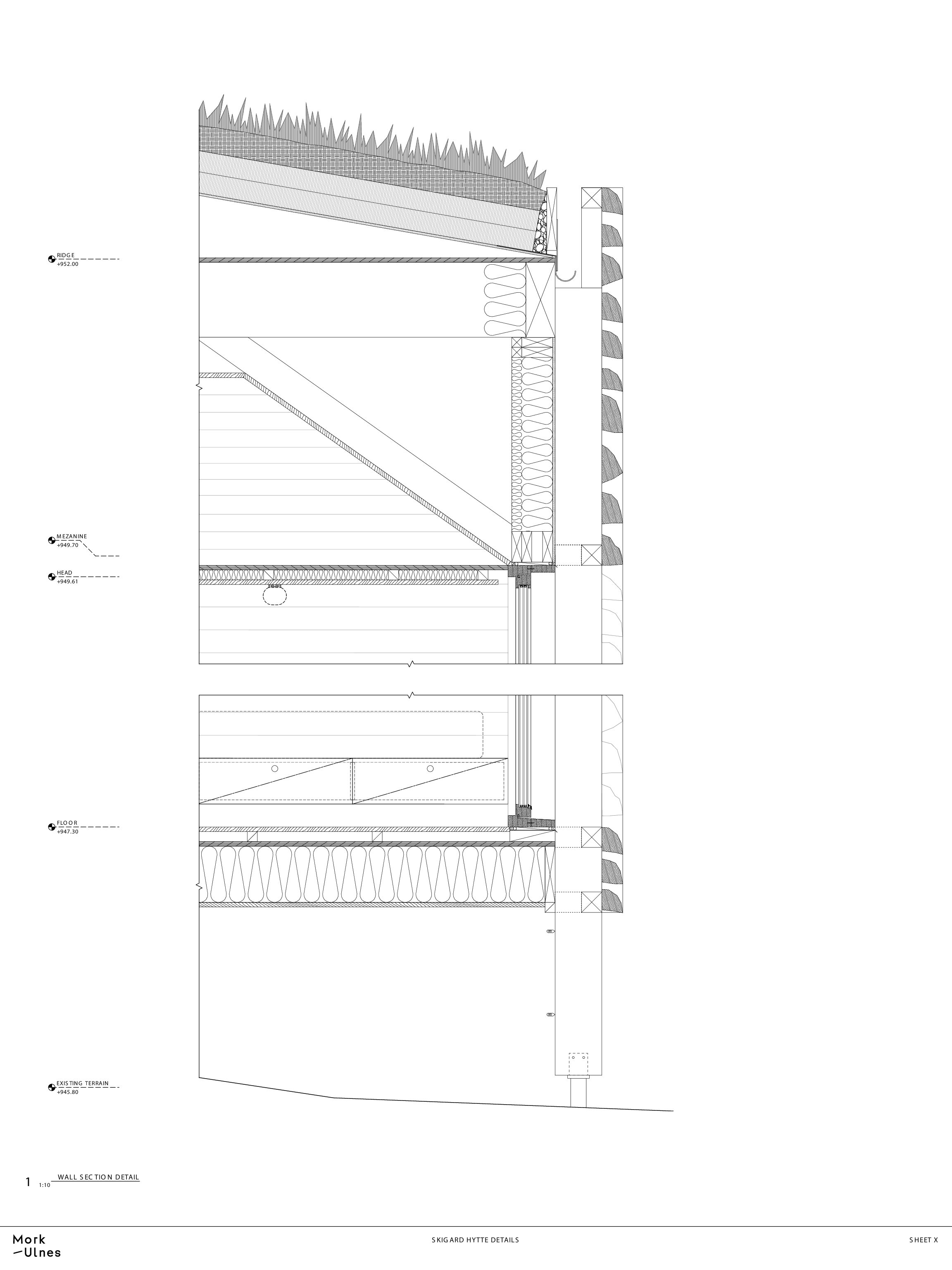

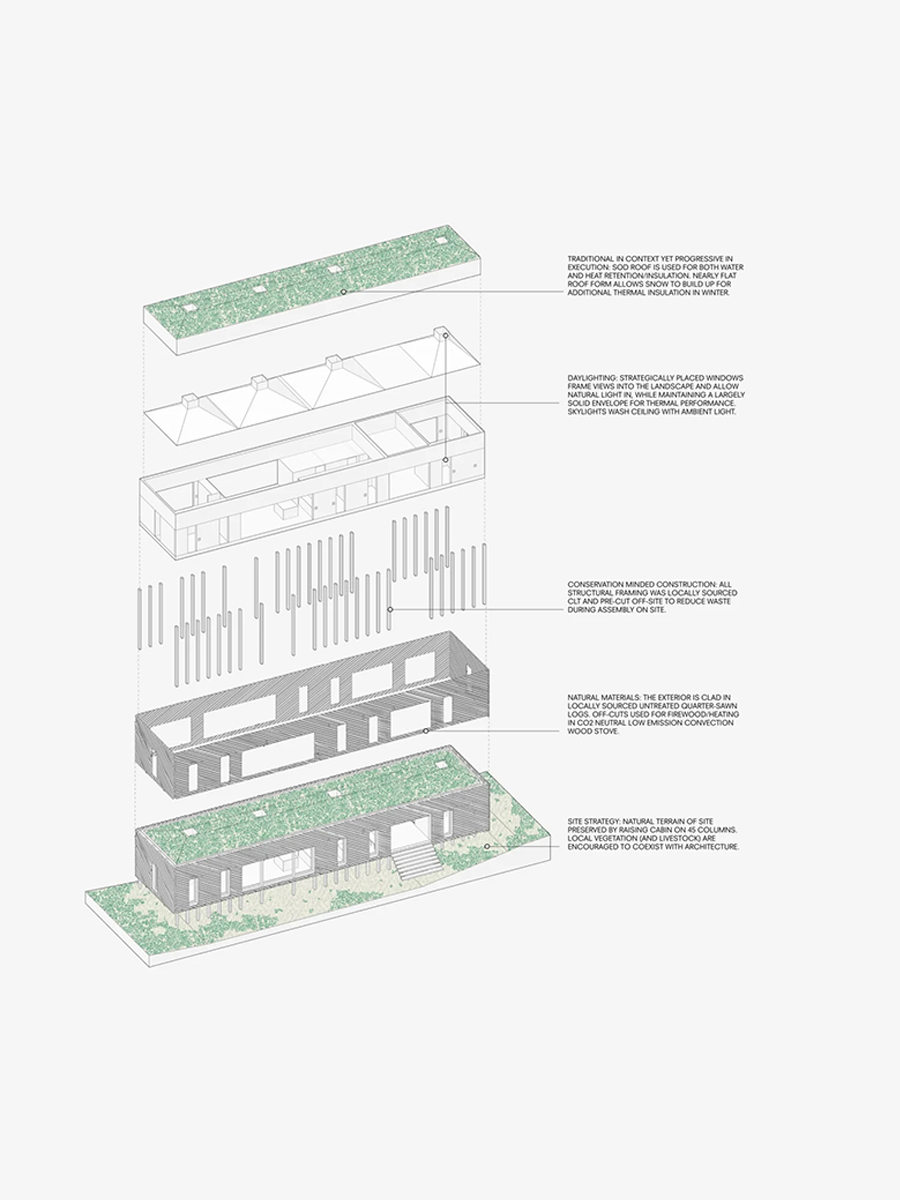

Skigard Hytte

I’ll share a bit about the Skigard project, which is personal as it’s our own family cabin that I share with my wife and kids. Designing for ourselves allowed us to explore ideas in ways that can be difficult with clients.

The concept is closely tied to the culture of the valley where it’s located, so the surrounding landscape and heritage shaped the project in many ways. We aimed to create a cabin entirely of wood, one that would age naturally over time, and that would feel like a true part of its surroundings—in both appearance and function.

Because it’s our own project, we could experiment with materials and construction methods that might be considered risky, such as using traditional fencing materials as cladding or building the bathrooms from wood. The result is a cabin that is both rooted in the cultural landscape while also allowing for exploration —a space we think feels genuinely of its place.

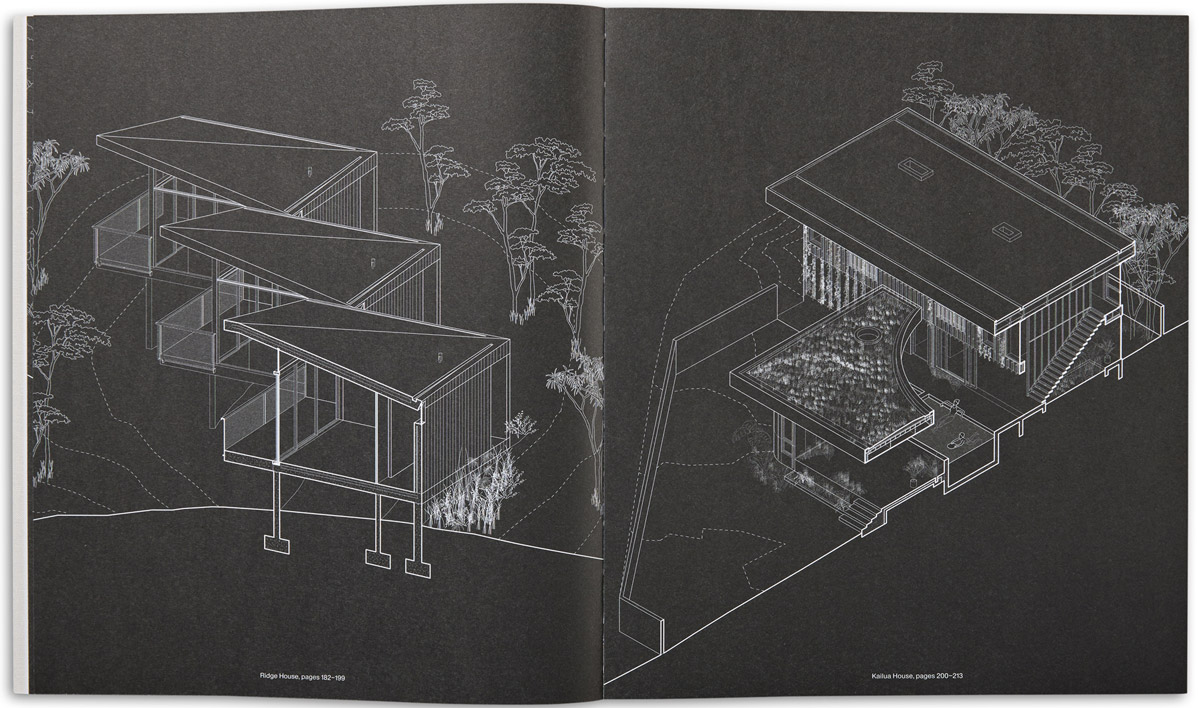

Project 2

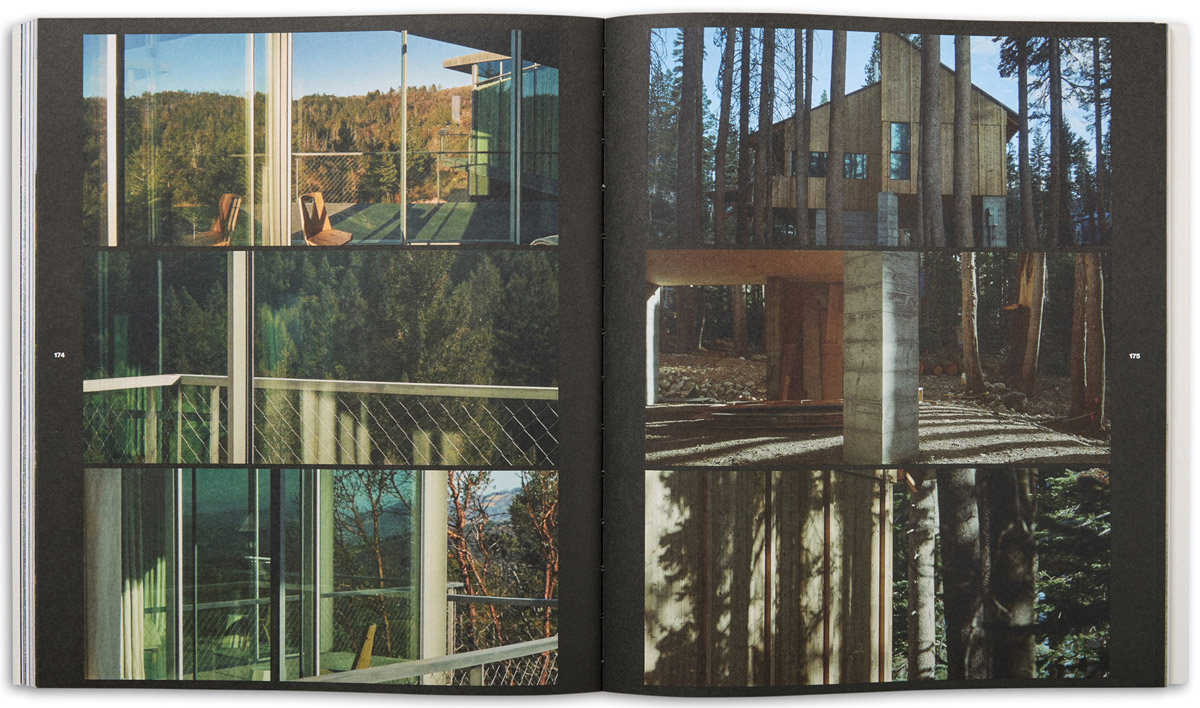

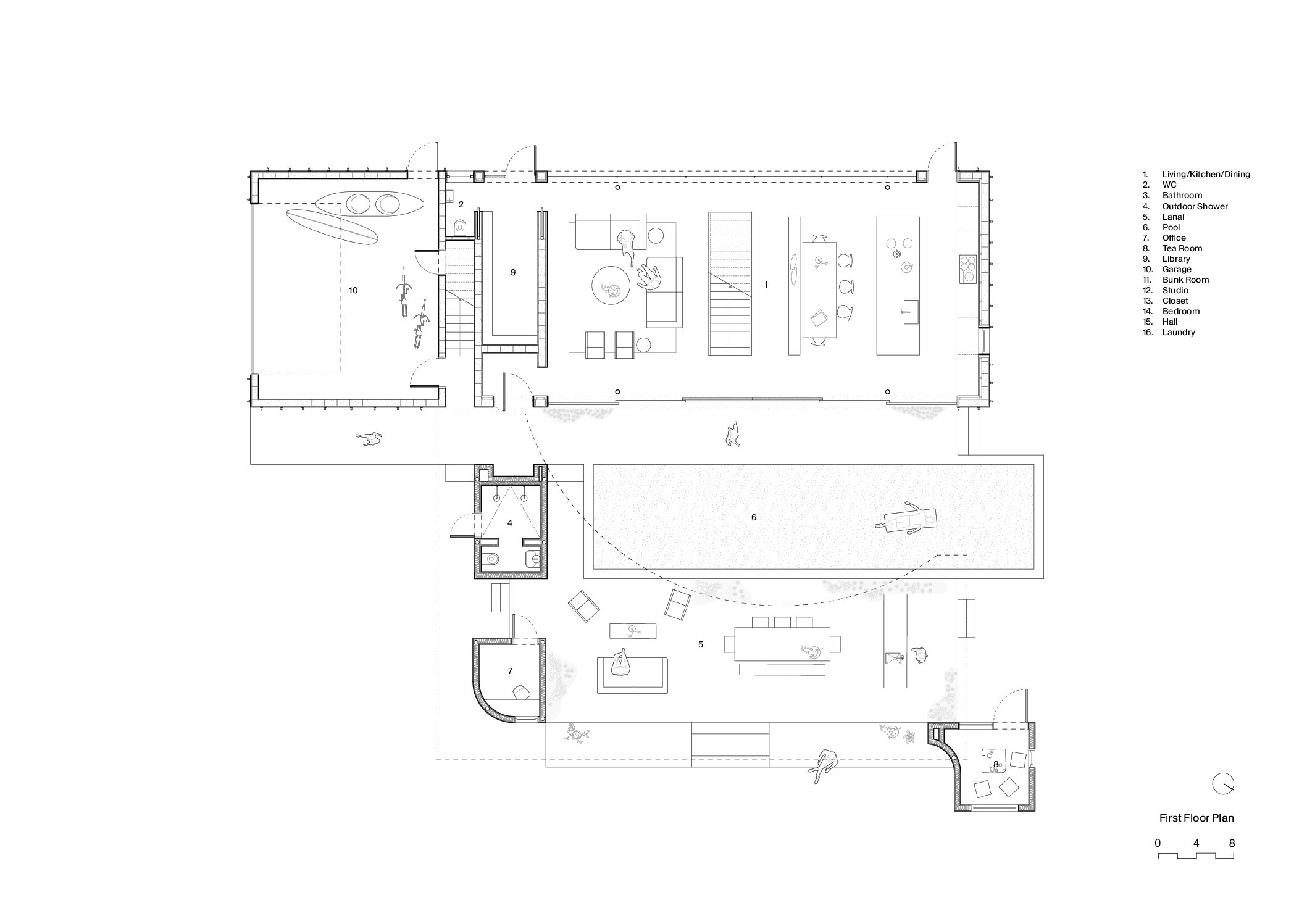

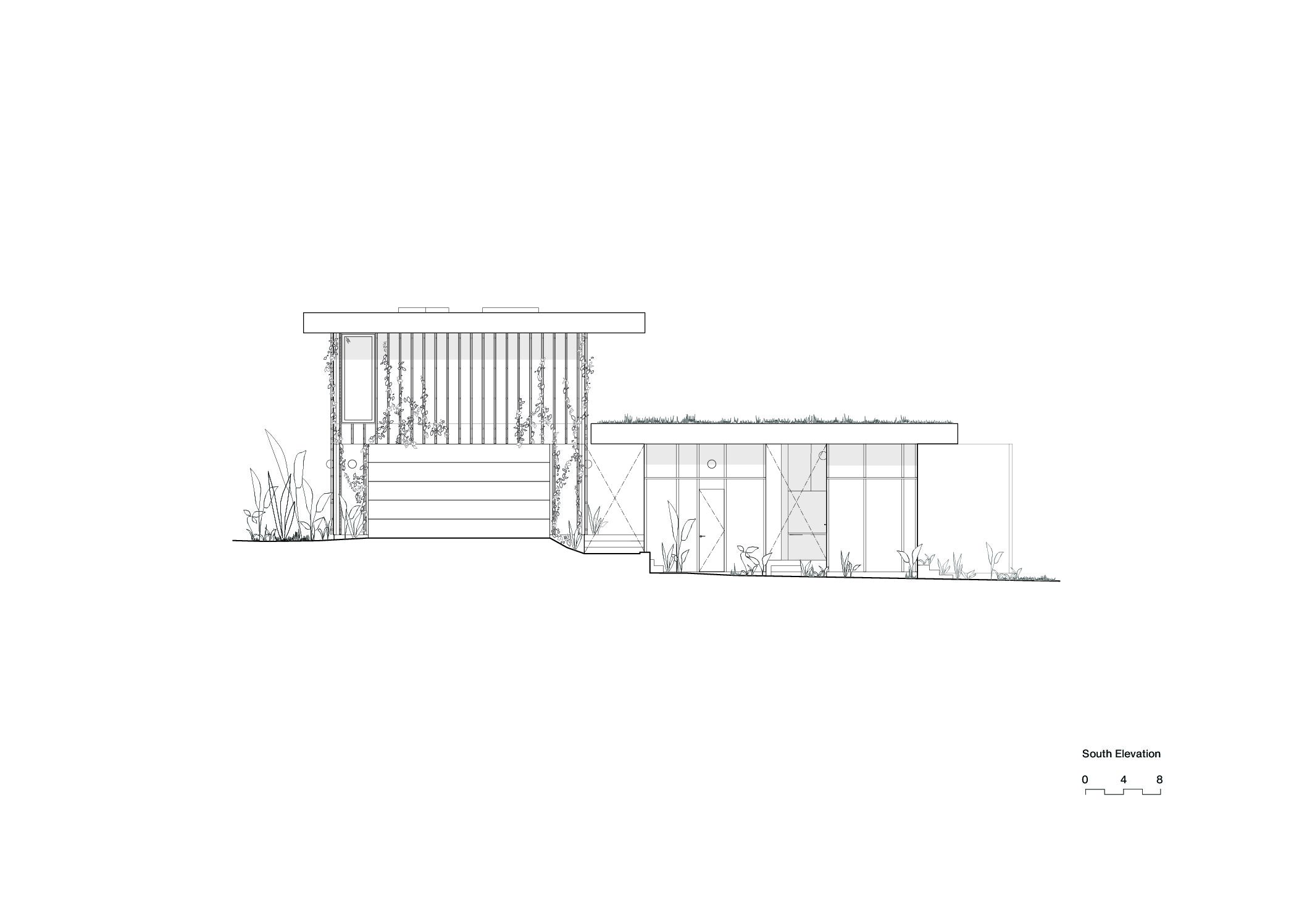

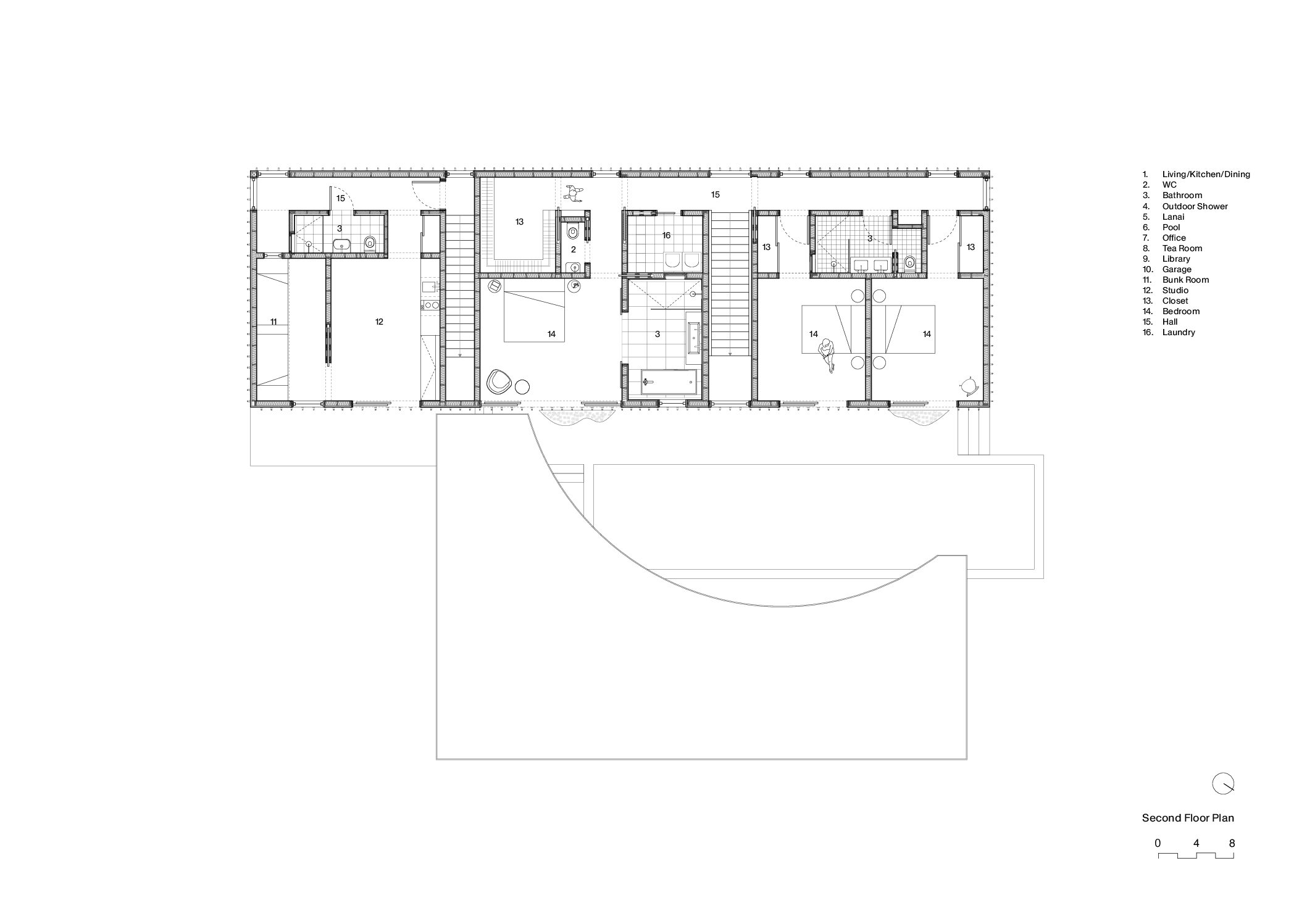

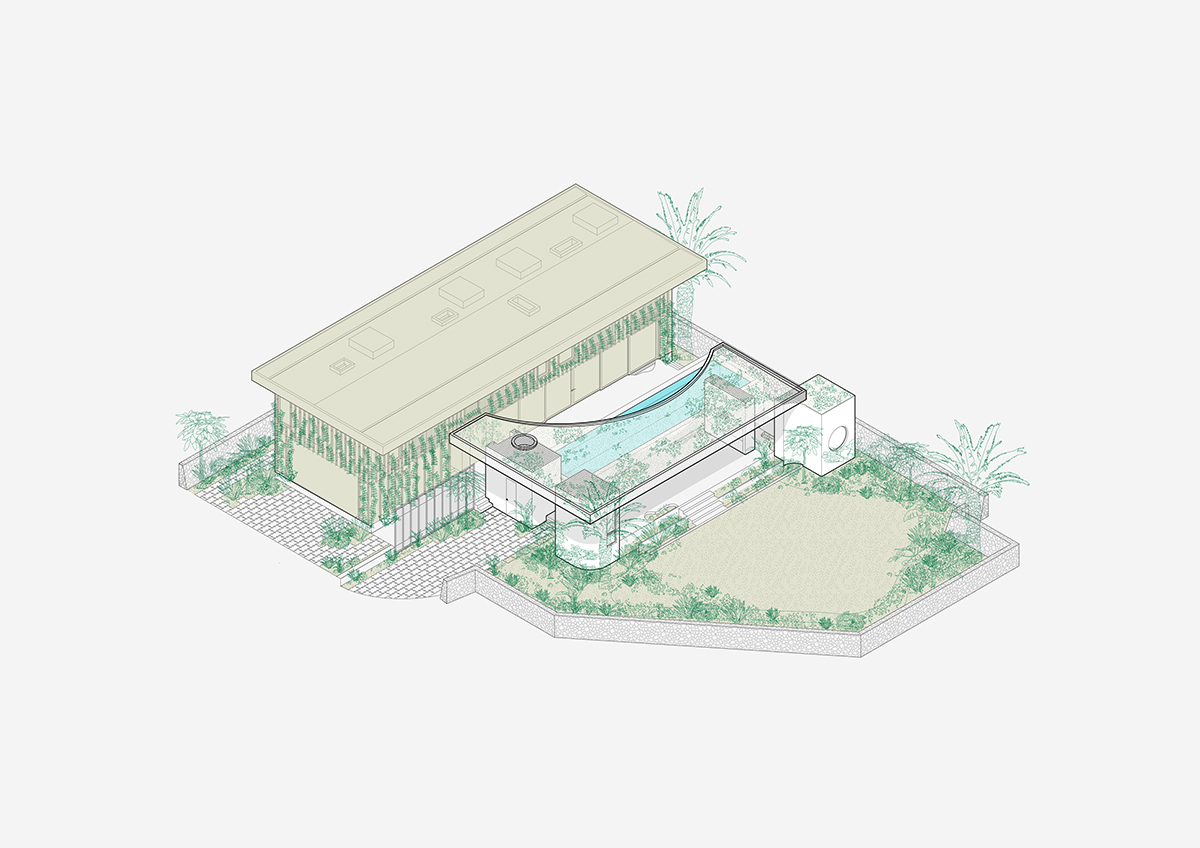

Kailua House in Hawaii

On the other side of the world, Kailua House in Hawaii stands in stark contrast to our Skigard project — culturally, climatically, and geographically. I wanted to share this project because it raises questions as we expand beyond the two regions we have focused on for the past 20 years.

The projects are similar in that both Skigard and Kailua houses use familiar modernist techniques to connect visually and experientially with their surroundings, like creating a strong indoor–outdoor relationship. However, in Hawaii, the house turns inward around a central pool with the help of a lanai. A lanai is a covered, open-sided porch or veranda that extends the living space outdoors, common in Hawaiian architecture. Here, we reinterpret the lanai to focus the house inward toward the pool and the family’s living area, activating the heart of the home both inside and out.

Similarly to Skigard, the building’s skin reinterprets a traditional local construction method. Board-and-batten cladding is used, but vertical wooden dowels cover and protect the joints while also encouraging vegetation to grow over time, allowing the house to gradually merge with the landscape. In many ways, this parallels how the Skigard Cabin skin adapts local methods of construction in the skin. Hopefully, this is an example that demonstrates that our approach can carry across very different geographical settings, and we are excited to continue this working this methodology as we work in different locations beyond our bases.

Kailua House

Drawings

Website: morkulnes.com

Instagram: @morkulnesarchitects

Photo Credits: © Bruce Damonte (Skigard), © Joe Fletcher (Kailua House; Creston House), © Hanna Kjellberg-Line (Portrait)

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 01/2026