21/005

Max Otto Zitzelsberger

Architect

Munich / Kneiting

«The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.»

«The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.»

«The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.»

«The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.»

«The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

My name is Max Otto Zitzelsberger and I am an architect working in Bavaria. The studio has no real founding year. In 2010 I started an assistantship with Florian Nagler. In 2011 I worked on my first project all on my own—a 4 sqm chicken coop. Over time the number of projects grew slowly and with it as well the size of the projects. The step into self-employment was more of a slow process than deliberately planned. Today the office consists of two employees and three interns. In parallel to the practical work, I am also actively teaching. Since 2019 I am holding a junior professorship at the Technical University of Kaiserslautern.

Max Otto Zitzelsberger © Jens Schnabel

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

I discovered architecture by chance. It seemed as if I had no talent at school. Only my achievements in drawing were alright but I didn’t have the confidence to study design. Architecture, as I imagined it at the time, corresponded best to my petit-bourgeois and conservative world view. During my studies, however, I was constantly insecure. I only realized that architecture was really something for me after I graduated. As a freelance architect, you can determine your own work. It doesn’t matter whether you build, write, plan, research, teach or design. To know that all of these areas are part of the profession is what excites me about the profession. You need many skills and you learn something new every day.

What are your experiences founding your own practice?

Admittedly, I am not a good collaborator. Implementing and realizing other architects’ ideas doesn’t make me particularly happy. Therefore, I had no other choice but to become self-employed, what comes with a lot of difficulties, not only financial ones. The main challenge is to position yourself: You first have to be clear about your relationship to the world, which means—put simply—finding your own path in life just like in Paulo Coelho’s novel “The Alchemist”. Designing is the struggle for an idea. The most difficult part of the process is to convince yourself.

What does your desk/working space look like?

How would you characterize the place you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture?

I live both in Munich and in Kneiting, a small village near Regensburg. There is no immediate influence of these places on my projects. However, I cherish the countryside and the everyday architectures of the Bavarian periphery have a clear influence on my work.

I grew up in the outskirts of Landshut, a small town in Lower Bavaria. My parents, both civil servants, settled there and bought a semi-detached house in accordance with social expectations. In the context of this uninspired environment the annual vacation trips to the Berchtesgadener Land, stood in strong contrast to my everyday life at that time, I have developed a deep longing for rural idylls. Especially in my first projects a part of this romanticism is inscribed.

The longing for tranquility, however, became rather suspect to me over time. The “everyday” (whatever is to be understood by the expression) continues to function as my source of inspiration. But it is no longer the romantically charged “everyday” that intrigues me today, but rather the banal, which at first glance does not seem to be worthy of closer examination. But upon closer inspection presents itself as an almost inexhaustible treasure trove of architectural moments: strange houses, peculiar situations, unusual circumstances, surprising materials, bizarre cubatures, etc. All this is rarely found in buildings designed by architects, but in conventional houses!

Beyond that, I draw a lot of strength from literature. It is not the source for specific designs, but rather a source of context for the process of creation. Every form also needs a justification, a rationale, a reason. Literature sketches precisely this context and shows diverse alternative worlds. Just recently, I had a very inspiring encounter with a fictional person named Daniel, the main character in Michel Houellebecq’s novel The Possibility of an Island. When I read stories, I’m particularly receptive to ideas; pieces of thoughts often come together as if by themselves.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

The essence is for sure not tangible. It is always new, always different. Can be redefined again and again. Is everything and nothing. Thank God architecture cannot be defined in general terms otherwise it would be a horribly boring subject. For me personally, the thought is the foundation of architecture. The thought is more relevant than the house itself. Building is important, but thinking is even more.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you?

This is an important question and it is not easy to answer. At first glance, there are countless points that could be listed here: the German competition system, the VGV procedure, the distribution of opportunities between small and large offices, and so on. But the basic problem lies deeper. The architecture market in Germany is essentially limited to a very specific type of architecture. I’d describe it as “generally well tolerated”—a kind of “lowest common denominator”—architecture.

New design approaches, unconventional ideas, innovative thoughts and, above all, uncomfortable truths are difficult to mediate between all parties involved. In rural areas, for example, there is a strong tendency—especially among people with an affinity for architecture—favoring traditional forms (e.g. clear bodies, sloping roofs), traditional materials (e.g. bricks, wood, clay) and traditional facades (e.g. plaster, wood). Arguments are readily made about the historic sense of place and also about sustainability.

In the same context the term “sustainability” is broadly associated with wood for justified reasons. Anyone, who builds a wooden house normally wants to show this. But to be sustainable a wooden house could also be clad with metal. This construction lasts a long time and does not require much maintenance. However, this “other type” of sustainability is difficult to communicate in the aforementioned tradition-loving circles, as it is uncommon.

Further, the townscape of many rural communities is now dominated by a wide variety of typologies: Warehouses, gas stations, commercial halls, factory buildings and prefabricated houses consisting of all kinds of forms and materials. Villages and communities are dominated by a superposition of heterogeneous appearances. The historic townscape is only intact in very few places. Especially for experts in the field of rural construction, it is therefore all the more important to protect the original townscape and to defend it by all means. This attitude has a long tradition and is still partly justified.

Nevertheless, I am no longer convinced that it is the only sensible strategy for building in rural areas that can be justified in every case and under all circumstances.

Particularly in conservative milieus, new ways of looking at things first have to assert themselves. This has never been different. Looking at recent architecture from Belgium or France leaves me with a positive perspective though: there is a growing interest in new architecture and other points of view.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

As already mentioned, I have been teaching at various architecture faculties since 2010. In my experience, many students have a peculiar concern: they always want to get everything right. I consider this problematic: This is how you forget to think. This is how the expected is created. This is how any will to change dies. That which presents itself to us as “normal” often seems to be unchangeable and therefore leads to supposed powerlessness. Only an alert mind and a critical eye can counter this. The norm must always be questioned. It must always be checked anew whether it still does justice to the current circumstances. This desire to reflect and to doubt is vital.

Hermann Czech, whom I highly admire, was once asked what he tries to pass on to his students. He answered succinctly: “A maximum of confusion”

Our world is paradox, incommensurable, non-pure, heterogeneous, manifold, multilayered. We are best equipped for the future if we learn to deal with complexity and contradiction.

How do you imagine the future? What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

The growth-oriented development of the (Western) world is highly problematic. And it is well known why this is the case (cf. climate crisis). Neo-liberal economics and politics preach since the 60ies that societies only have a future if they grow economically. Many people still assume that growth is the default state. But human history has produced many societies that were not interested in economic growth and still achieved great innovation and progress over centuries.

There are well-written books that make intelligent suggestions on how to get out of this kind of mess. But these ideas do not bear fruit. This realization is shocking. But we forget that it is precisely in the visual arts, in literature, in film or in philosophy that alternative models of our world are constantly being sketched out. Specifically, the question is formulated whether everything could not be completely different. This is how islands of new perception are created. The above-mentioned industries do not change the world, but they can help to change people, who then translate their new convictions into action.

Built architecture—real estate—bears the problem of being part of the growth-oriented economic system we live in. In my opinion, “architecture” which is capable of changing something must adopt the above-mentioned strategy of art and philosophy, not to give answers, but to pose questions. Instead of claiming a truth about what is right or wrong. Architecture should stimulate reflection. It should be less the key to sustainability or an expression of social responsibility, than a medium for making social processes understandable. For me, an “architecture” of the future is not one that spreads ideological slogans, but one that manages to unite the contradictions of our world.

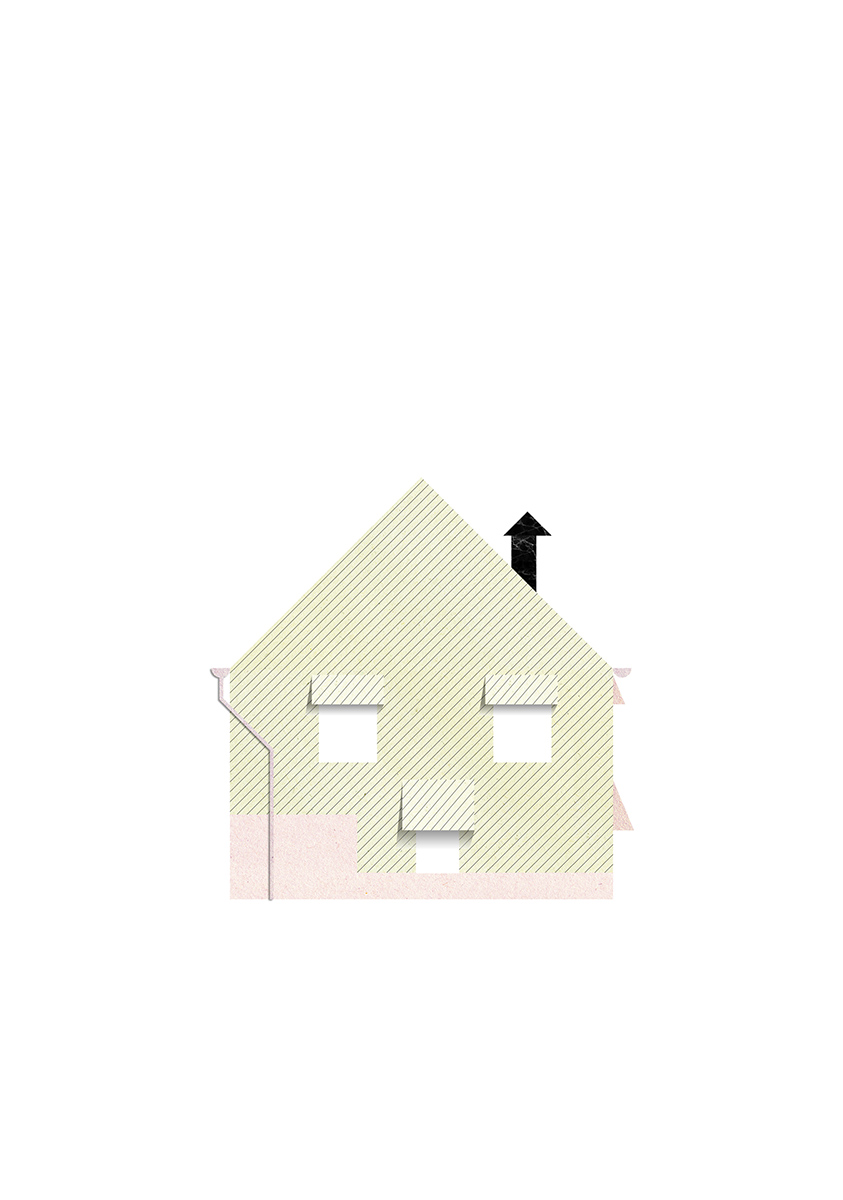

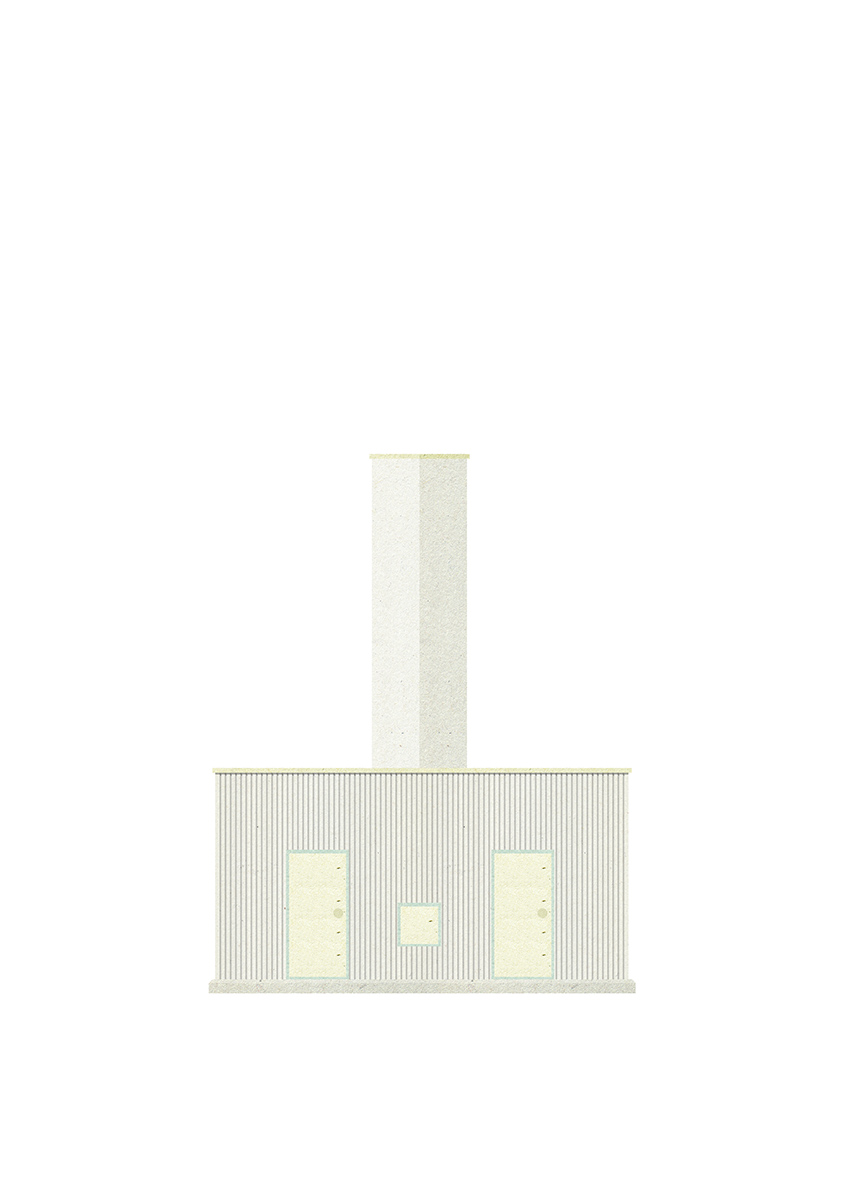

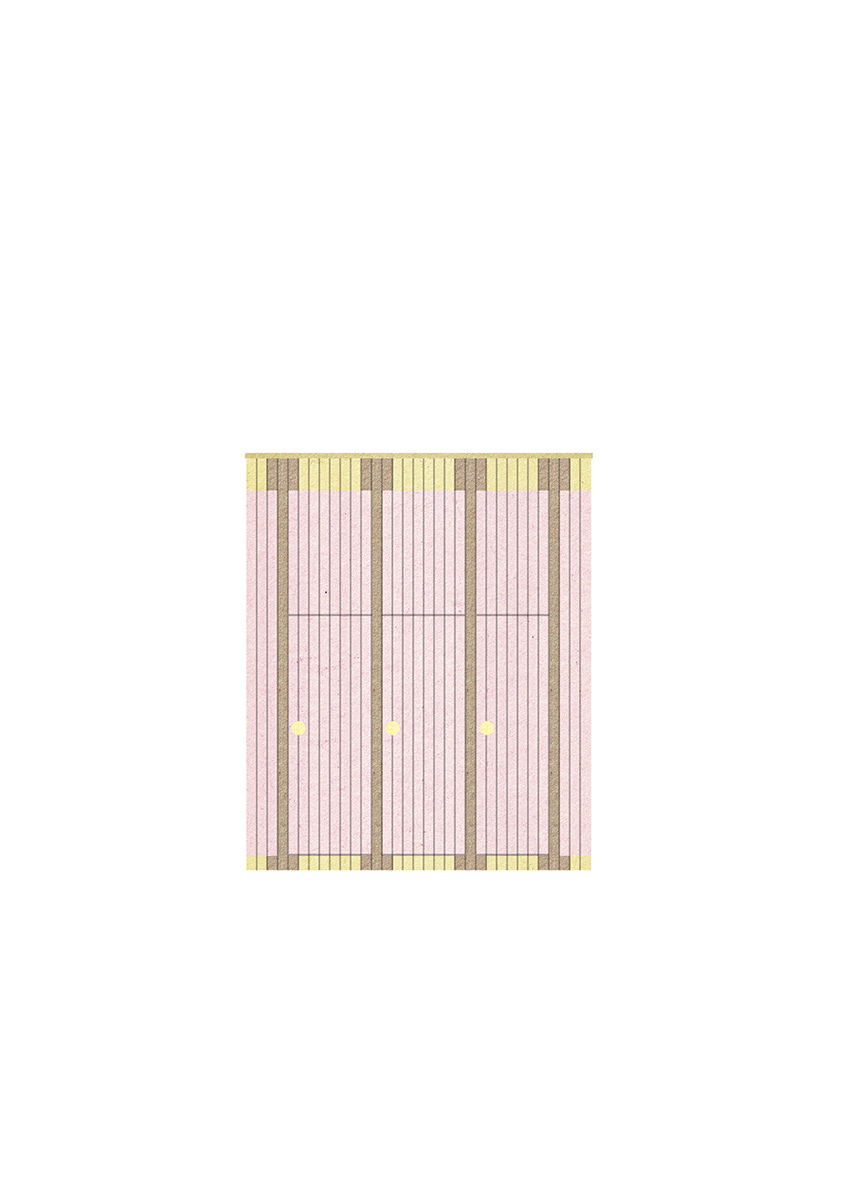

Project 1

Erkläranlage

Berngau

Berngau is a village in eastern Bavaria (Oberpfalz). The site of the old municipal sewage treatment plant is no longer in use and should be converted. There is still a trickling filter that was used to purify waste water until the 1990s. Berngau is known for its civic commitment to intergenerational justice and the active integration of marginalized groups. People with learning difficulties and also with intellectual disabilities are part of the community there. At the Berngau school, these young people are a natural part of the classes. The idea now was to build a green classroom in the form of a pavilion for the local schools and a local facility for mentally disabled people.

The fallow areas of the old sewage treatment plant are ideally suited for this purpose. The old trickling filter was not demolished, but integrated into the concept as a walk-in sculpture. Next to the pavilion there is a new fence. It provides noise from the main street and protects the children from the new clarifier. A bridge connects the way to school with the site of the old sewage treatment plant and is used for access. A wooden crown was placed on the trickling filter, which can be seen from afar. This underlines the importance of the green classroom and the social idea behind it.

Overall, an ensemble of pavilion, trickling filter, fence and bridge was created. The individual building blocks interact spatially. They are all at an angle to each other, as if they had arisen accidentally. Materials from the municipal building yard, containers and intermediate building materials can be found on the site. This should stay that way. An old tar area in front of the pavilion is also not to be renewed for the time being. The central idea is to celebrate the state of incompleteness. Imperfect spaces are always interesting for children—in sociology one speaks of possible spaces. The so-called wastewater treatment plant (in German “Kläranlage”) becomes an explanatory plant (in German “Erkläranlage”). The new site will become an enabling space.

The pavilion is somewhat reminiscent of a Greek temple. It stands on a massive base protruding from the earth. The main reason for this is the flooding in spring. The trickling filter, with its ideal construction and fine ribs, is reminiscent of a round temple. The whole ensemble of pavilion, trickling filter, fence and bridge looks a bit like an acropolis. Here, too, the individual architectures appear to be fortuitously side by side.

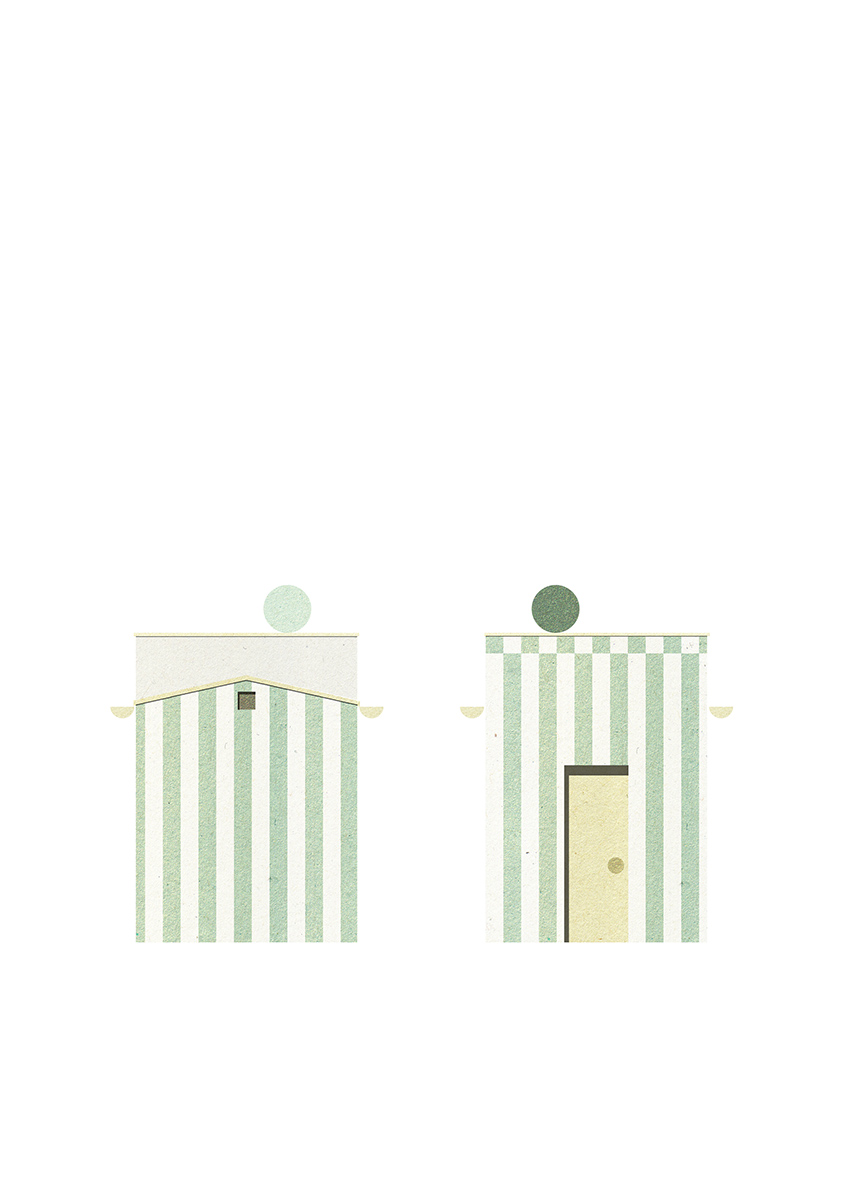

Project 2

Wartehaus

Landshut

The tram stop at Bismarckplatz in Landshut is a reminiscence of all the metallic objects of our 19th century cities, which functionalism has exorcised the shape of. I’m referring to all the wonderful railings and balustrades, the little toilet houses, advertising pillars, streetcar stations, flower kiosks and street lamps. It is not my goal to re-establish these objects as reconstructions. But I look with great sadness at the furniture of our cities. It is the boring billboards, the meaningless trash cans or urinals, or even the petty bus or streetcar shelters. They are all united by a great emptiness of design.

Yet we could learn so much from the 19th century. It celebrated craftsmanship with great vigor, yet was shaped by industrialization like no century before. This mixture has produced fabulous buildings. The construction of the small stop with the clock tower standing freely next to it is of course made of metal. The corner supports are prefabricated sections with welded-on components. The intermediate supports are laser cut from metal plates. Contemporary manufacturing methods are important and of great significance for the construction industry. The components are bolted together. The details of the chosen design are reminiscent of the classic “bundles” in blacksmithing or the rivets on the bridges of the 19th century. The paint is a micaceous iron varnish applied with a brush. Thus, traces of the hand appear, which in your uneven ductus breathe life into the cool construction. Highly industrialized methods and those of classic craftsmanship are to merge into one here and restore a bit of urban nobility to the prominent site of the medieval city of Landshut.

Website: www.maxottozitzelsberger.de

Instagram: @maxottozitzelsberger

Text + Drawings: © Max Otto Zitzelsberger

Photo Credits: © Sebastian Schels, © Jens Schnabel, © Mirjam Elsner

Interview: kntxtr, ah+kb, 03/2021