21/003

Nidus Studio

Architecture + Real Estate

Düsseldorf

«Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.»

«Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.»

«Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.»

«Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.»

«Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

We are Ana and Annelen and founded Nidus in 2016 shortly after meeting each other during our real estate studies in Frankfurt. Before, Ana worked as a lawyer in an international law practice, Annelen worked as an architect in a large architecture studio in Cologne. Coming from different backgrounds, our aim with Nidus was to create an interdisciplinary studio to develop existing properties in particular, to play an active role in urban development by designing new concepts, spatial programs, etc. and to take part in communicating architecture and in communicating what we call “Baukultur” in Germany.

We understand ourselves as preservationists, both concerning redevelopments and new developments, weaving our projects into the urban or rural context. In our studio we overtake all parts of the real estate value chain: acquisition, financing, development strategy, architectural design of all phases, realization and marketing. We believe that, unlike the preconceived notion, none of these stages are opposed but instead stimulate each other and can be carried out very creatively. At the moment we are a team of eight people consisting of architects, lawyers, economists, accountants and assistants.

Ana Vollenbroich and Annelen Schmidt-Vollenbroich founders of Nidus Studio / © Marie Kreibich

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

Annelen wanted to become an architect since she was a child. During her childhood, she moved a lot with her family, getting to know different countries, cities and housing typologies. From “planning” houses for her friends in school and kindergarten, drawing floor plans during class and building doll houses instead of playing with them, she moved on to study architecture first at KIT Karlsruhe then at ETH Zurich.

As a lawyer, Ana has experienced the “behind-the scenes” of a building process being responsible for all law related aspects. Being fascinated by the building industry and architecture in particular she ultimately wanted to switch sides and play a more active role.

Having studied philosophy before engaging in law, Ana’s interest in architecture is also fueled by a desire to learn about the motivations and backgrounds of human cohabitation and other socio-philosophical aspects of architecture.

What are your experiences founding your own studio?

We started the practice with our project Stadthaus Kaiserswerth. The project consisted of two city houses built around 1880. When we purchased the houses, they were in a very bad condition. A lot of people declared us crazy to buy them, especially bearing in mind that though we both had our work experiences in other fields of expertise we had never before undertaken a redevelopment—let alone one of that kind of scale. But our determination to make it work and also to work together as a team was so strong, we blew all doubts aside.

Apart from that, we strongly believed in the neighbourhood of the project. Both houses are located in Kaiserswerth—a part of Düsseldorf we identify and feel at home with. Looking back, we now know why people called us crazy—we started out so very naïvely and just went with the flow. Getting in touch with financial institutions, setting up a working business plan, building a team of architects and engineers, developing strategies how to use and transform the existing structure and finding users—we just tried to take one task at a time.

The developing, architecture and building industries are extremely male dominated and as women we experienced that our gender often gave rise to condescension and difficulties to be taken seriously. Also, we got the impression, that our preparation had to be flawless whereas a male colleague might have gotten away with a more nonchalant approach—especially with regards to so-called hard facts such as business plans and finances. However, now, almost five years later we see that along the way there were also quite a few people (often men) who believed in us and supported us, and we are very grateful for such luck.

How would you characterize Düsseldorf as location for practicing architecture? How is the context this place influencing your work?

Düsseldorf is a city that has to face a lot of prejudices. We both originally are not from Düsseldorf, so when we started working and living here, we tried to develop our own reading of the city. In our understanding, Düsseldorf represents two poles that are perfectly shown in two buildings: the Dreischeibenhaus designed by a group of architects around Helmut Hentrich in 1957 and the Schauspielhaus by Bernhard Pfau in 1965. The first stands for the economic strength Düsseldorf is known for, the second represents the cultural richness you can find in the city. The two buildings are located right next to each other. For us, they represent the heart of the city. We feel inspired by both sides and see ourselves and our work located in between this tension field. While designing our projects, we always have both the economic stability of a project as well as cultural aspects such as the history of architecture, living typologies, urban development processes, socio-cultural aspects of living together, construction technologies and sustainability in mind.

What does your desk/working space look like?

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

We understand architecture as a mirror of society. Our responsibility as architects is to develop a reading of our society and the different forms of coexistence in order to find answers in forms of buildings, interventions, etc.

Architecture is our language to communicate our reading. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe once said, you have to have a grammar to speak a language. And if you are really good, you could be a poet. This quote shows that architecture has a huge emotional component which—in our opinion—in times of standardization, normalization and efficiency is often pushed to the limits. We feel the aspect of emotion, flair and instinct has to be given more space in designing our built environment.

Whom would you call your mentor?

We wouldn’t say that we have a mentor. But there certainly are some people who influenced our way of thinking, some of who we would shortly like to name:

Werner Sewing, former professor for architectural theory in Karlsruhe, arouse our interest in history and theory and showed us to always take a deeper look into the socio-cultural background.

Georg Vrachliotis, professor for architectural theory in Karlsruhe, now Delft, showed us how to tell a great story starting with a small detail. This form of storytelling not only taught us how to set our work into a greater context but also introduced us to the pleasure of researching.

Antje Freiesleben, architect and professor from Berlin, invited us to question the topic of rule, exception and coincidence.

Christian Klugewitz, entrepreneur, showed us how to persevere, bounce back, and not lose our trust in ourselves or others and to believe in a bit of luck if you just keep your eyes open.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

In our daily work, be it in the beginning, in the middle or shortly before completion of a project, we are confronted with the question of appropriateness and durability. It seems that a large number of real estate developments focus either merely on the rate of return and/or are being built with materials that tend to serve certain industries with strong lobbyism more than other more sustainable causes like using local materials for instance.

We very much wish for a facilitation of building laws and norms to be able to build in an easier manner and to encourage traditional construction techniques which turn out to be very lasting and flexible. Also, we must not make the mistake and lose a strong sense of craftsmanship and build incentives for more individual solutions rather than prefabricated industrial quick fixes.

We feel that there is a rising community of developers, architects and users who want to change the deficits named above and work on more holistic concepts which motivates us to do the same. In our opinion, concerning the real estate market, the idea of return has to be expanded to be understood not only as an economic return, but also a social, architectural and environmental return.

What are your thoughts on architecture and society?

We feel that architecture or “Baukultur” should play a greater role in society. After all, amongst other important factors, our built environment significantly shapes the way we interact with one another, how we conceive our environment, how we move about in the public space and also how we define our own private space.

Therefore, we would appreciate it, if architecture and the history of architecture would become a part of the compulsory education schedules at schools. There should be a greater appreciation and understanding of the significance of architecture throughout society. Continuity and the appreciation of the existing built environment requires a holistic understanding, which at the moment is missing.

What is your approach on teaching architecture? What do you want to pass on to the next generation of young architects?

In our teaching there are two leading aspects: context and typology. Our work always evolves out of the precise analysis of these two parameters. What we try to pass on, is the understanding of context and typology as “reference”, a vehicle to understand the evolution and also a design tool. This not only includes a deep analysis of outstanding typology examples but also the analysis of typology interpretations on a broader more common scale, so-called “Alltagsarchitektur” or “everyday architecture”.

As we are mostly working with existing buildings, the question of durability of a typology, a structure or materials is omnipresent. In recent times, we were often confronted with the interpretation of our work as minimalist. We do not understand our aesthetics as a way of life, neither as an “austerity chic” as Pier Vittorio Aureli calls it in his small publication Less is enough. The aesthetics of our work, and this is an aspect that certainly plays another great role in our teaching, arises from the concept of simplicity of construction and from a choice of materials that are lasting and flexible.

We call our teaching/design approach “Denken im Rohbau” (“thinking in terms of building shell”) to develop resilient building structures.

How is your practice connected to (architecture) theory? How is the non-architectural background influencing your work?

Our studio being one for both, real estate development and architecture, is deeply connected to architecture theory, because we feel a profound responsibility to not only practice architecture as a service but are also held responsible for our concepts in so far that we can only be successful if there really is a need for those.

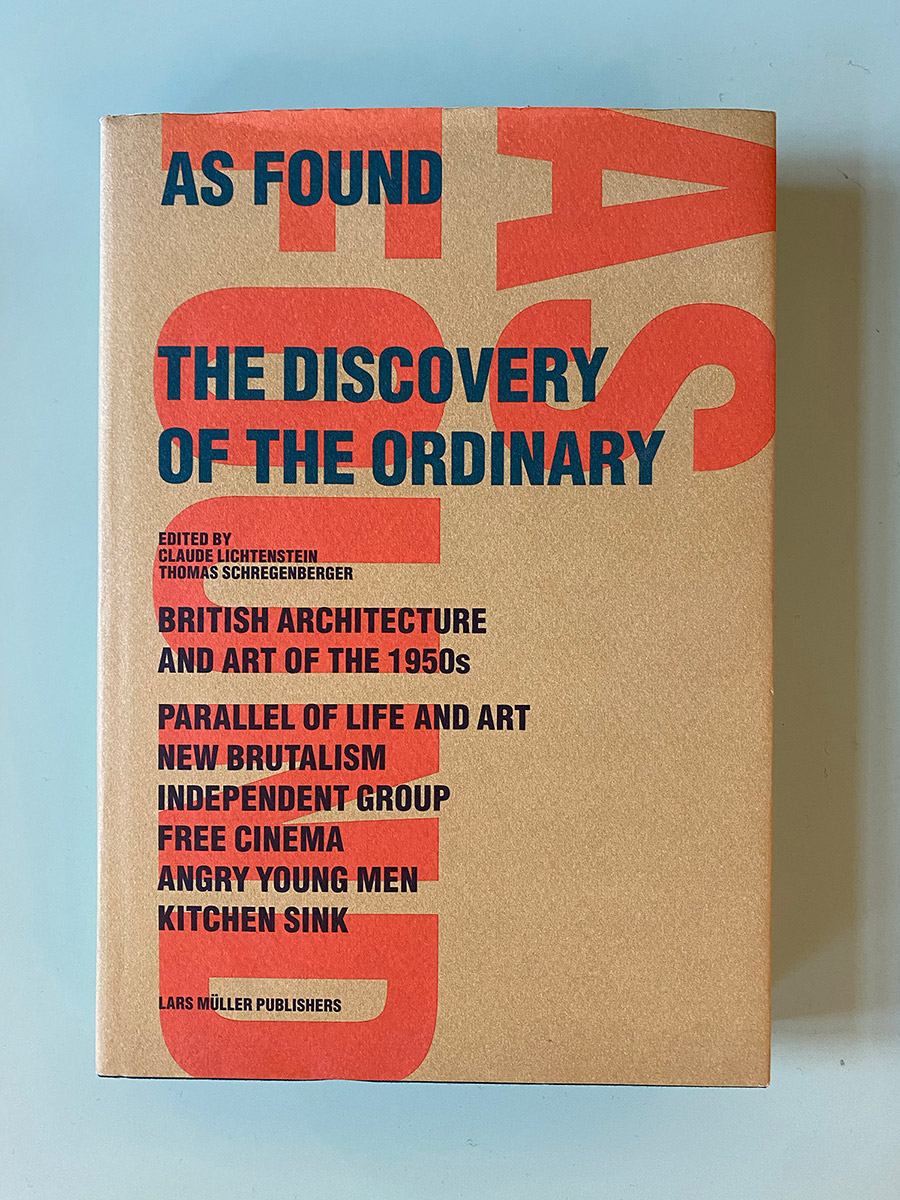

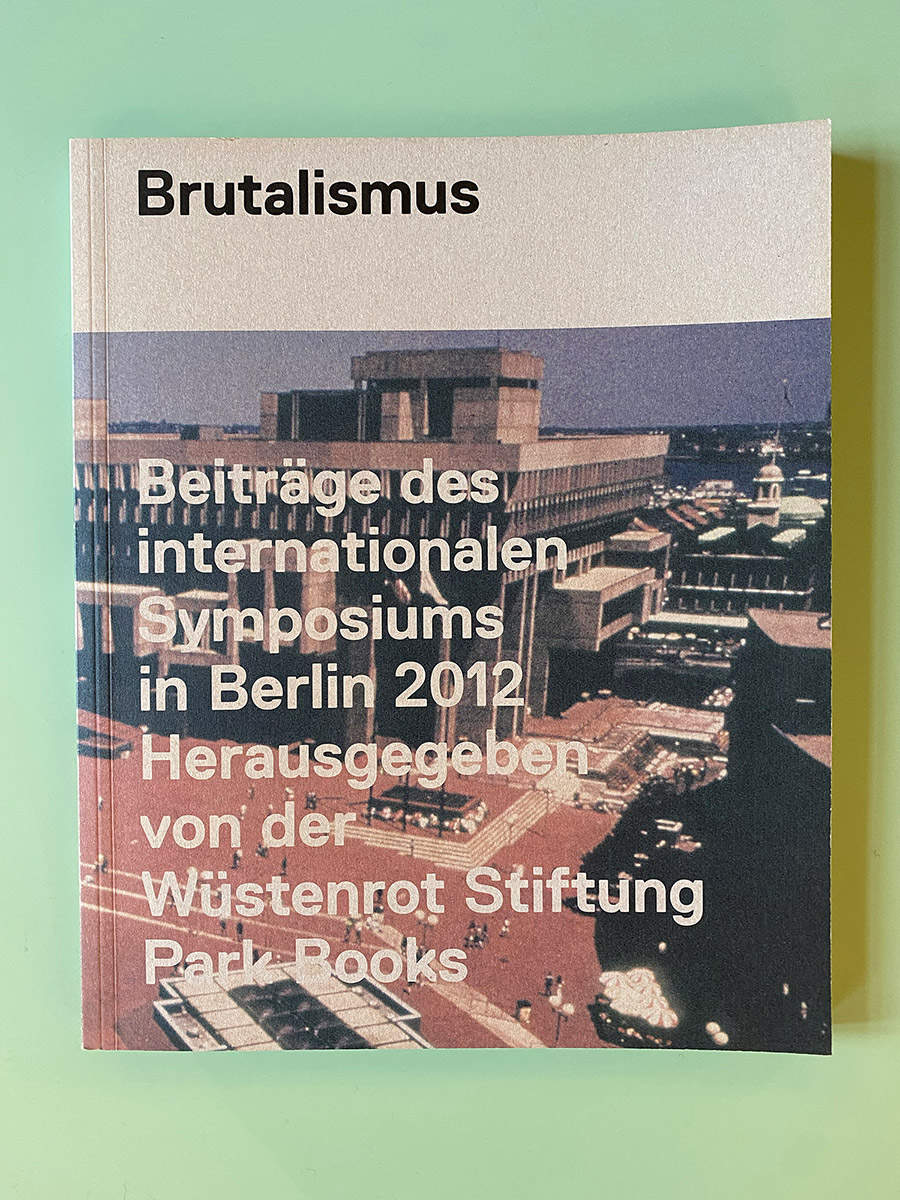

Annelens first project to work on after she graduated was a research project on Brutalism. During this time, the ideas of New Brutalism—the beauty of the normal, of the everyday, use of raw materials, a focus on construction, towards a low-tech architecture—have deeply shaped her way of perceiving architecture. Similar to the work of Alison and Peter Smithson and their “as found”-approach, we also design both trusting our gut with regards to material and proportion, and let our feelings guide us through the design process.

Anas non-architectural background is also not so far away from these ideas as one might think at first sight. As a lawyer, she was trained to separate the essential from the non-essential. This in a way has shaped her perspective on architecture and aesthetics in general. Therefore, her view on architecture might have evolved differently, however conclusively lead to the same architectural values.

Both law and architecture can be perceived as socio-cultural studies whose mere purpose is to serve people and give structure to the organization of human interaction, just from different angles. This take on architecture has helped us as we sometimes are under the impression, that architects are in a way brainwashed and dogmatic in their approaches. In these situations, especially Ana acts like a corrective, reminding us to stay focused and to not forget for whom our buildings are: we want our projects to be understood, used and loved not only by specialists but by a wider range of society.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

Be more open-minded towards the paths an architect can take. Interpret the creativity of shaping our built environment on different and wider scales than is often taught by architecture schools.

Project 1

Townhouses Sankt Göres

Düsseldorf Kaiserswerth

ongoing

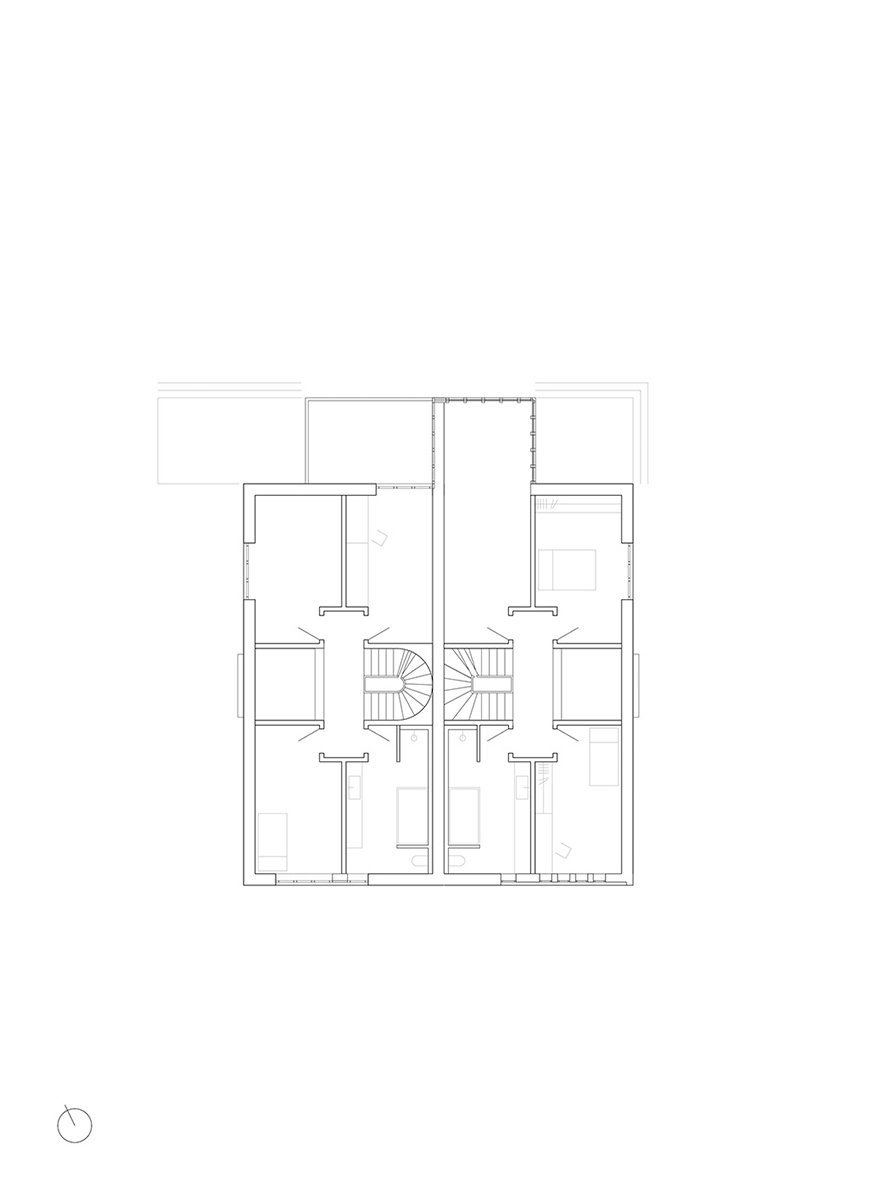

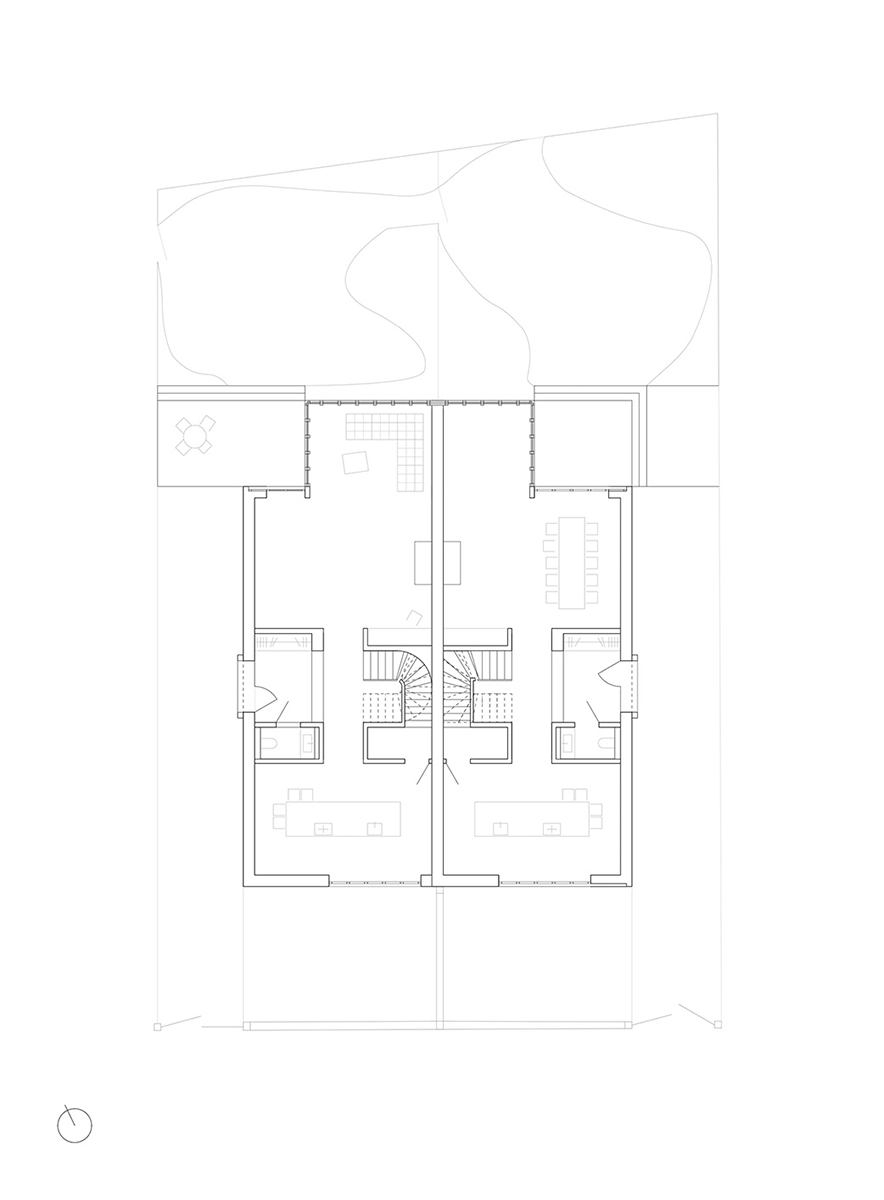

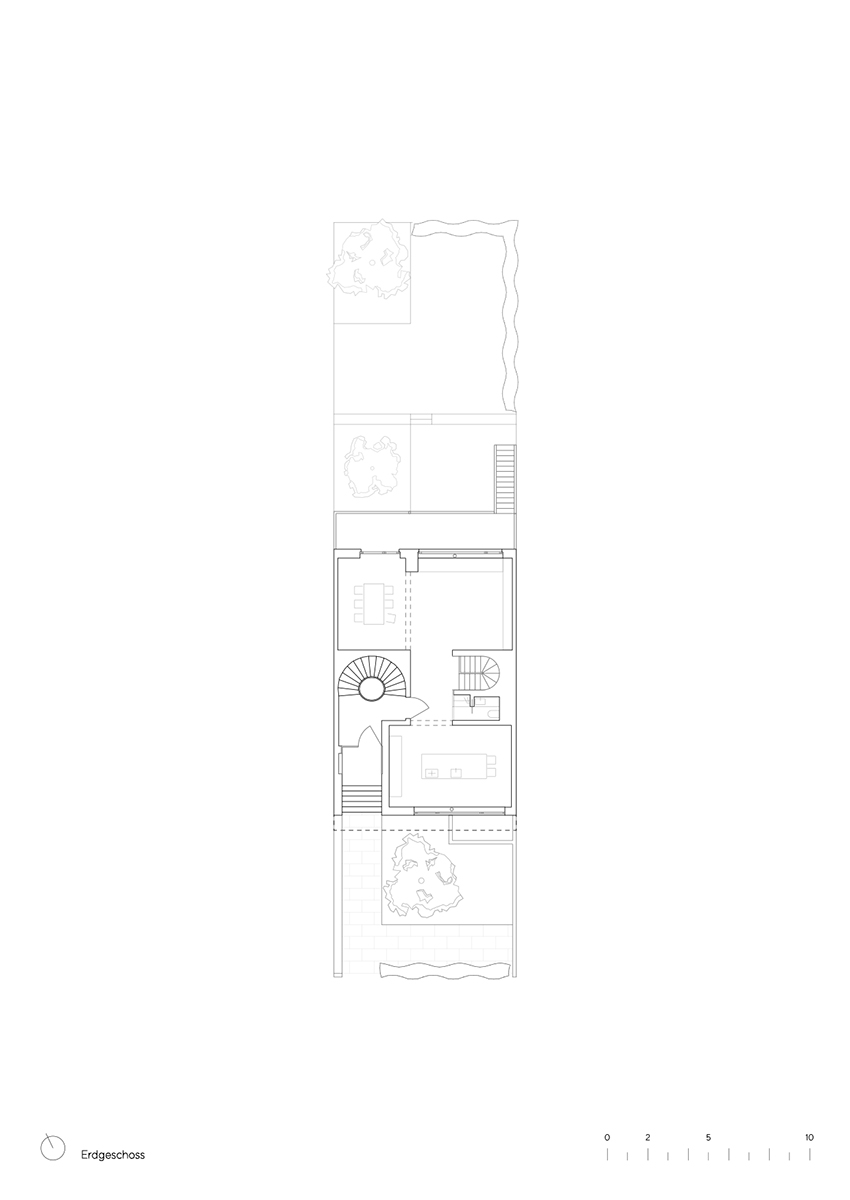

Developing the concept for our project “Townhouses Sankt Göres” we were especially taken by the implicitness and the longevity of the unagitated coy architecture that is so typical for Düsseldorf-Kaiserswerth. On the one hand, there is the “Kaiserswerther House” as a housing typology which is characterized by clear shapes, regional materials and a somewhat unconstrained reduction to the essential. On the other hand, the Diakonie buildings of the immediate context with their roman and gothic architecture are very formative for Kaiserswerth.

Bearing that in mind, our design is very much a contextual one. The surrounding architecture in direct proximity as well as the general architectural style in Kaiserswerth was key to the design in terms of the shape of the building, the façade and the choice of materials. The result is a new interpretation of the semi-detached house which plays with proportions and historic references while imbedding the building into a modern context. In reference to Kaiserwerth’s typical brick architecture the façade will be built of whitewashed brick. While being identical in structure, both houses find their individuality in the details. Both buildings are accessed through the side entrances leading to the heart of the building—the staircase. It forms the starting point of the internal development of the building which is symmetrical on every floor. Despite the shared identity of the building, each town house preserves its singularity and does not perish in uniformity.

Project 2

Bruno Lambart House

Düsseldorf

1955 | 2020

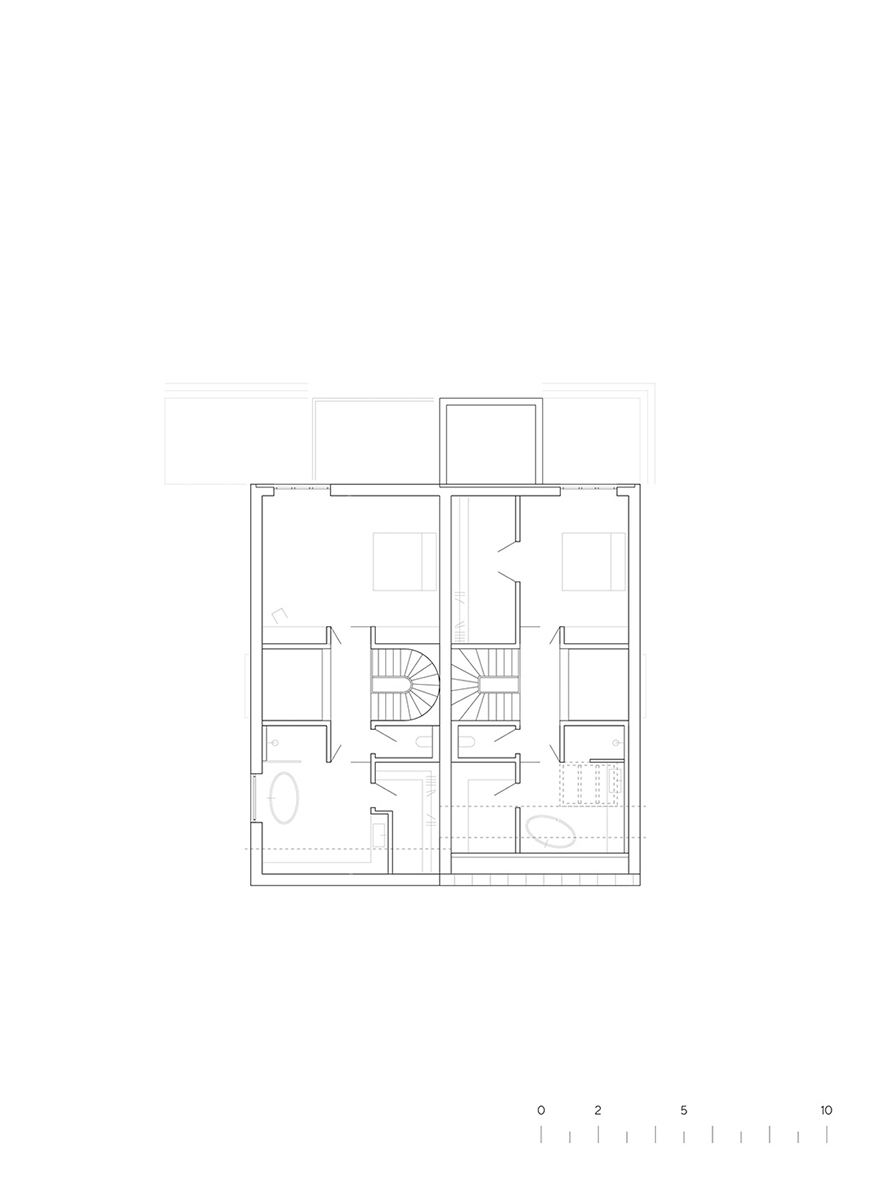

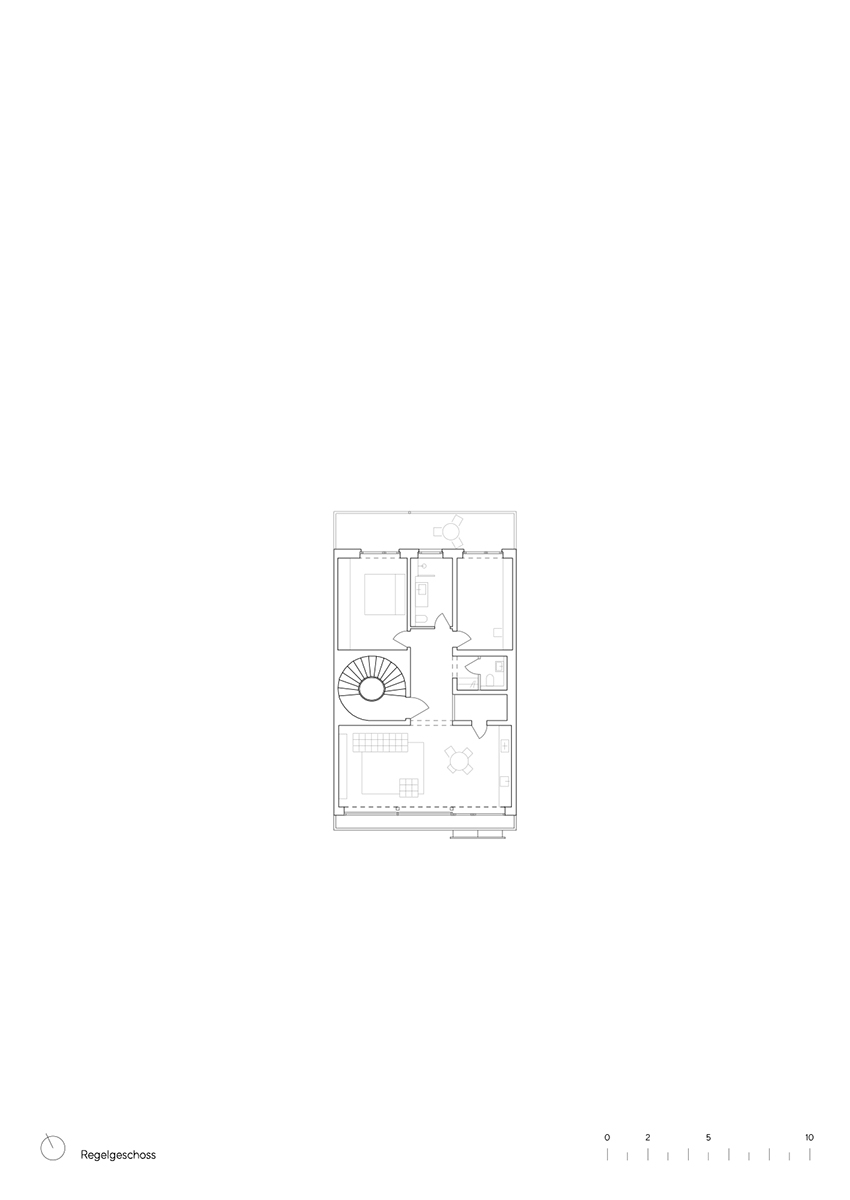

The multi-party house by architect Bruno Lambart was built in 1955. The house initially accommodated his first office together with Günther Behnisch while also serving as Lambart’s home residence. Lambart once described the house as the fundament to his professional existence and it was to remain the only residence building within his oeuvre.

As part of the design process of the renovation we consciously examined the architecture of post-war modernism. It was not long before we learned that this was an exceptional example of this architectural movement. Especially the floor plans and the structure of the house were way ahead of its time. With little intervention we were able to transform the structure and make it fit for modern demands. In addition to these smaller modifications, we wanted to combine a special emphasis on the defining features of the time, such as the spiraled staircase and the concise largely glazed street façade, alongside a contemporary reinterpretation. Haus Bruno Lambart, now accommodating five apartments, proudly retracts its history without losing touch with the presence.

Website: www.nidus-studio.com

Instagram: @nidus_studio

Facebook: @nidusstudio

Images: © Annika Feuss, © Robin Hartschen, © Marie Kreibich, © Annelen Schmidt-Vollenbroich

Interview: kntxtr, ah+kb, 02/2021