20/028

Oda Pälmke

Architecture Studio

Berlin

«Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.»

«Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.»

«Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.»

«Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.»

«Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

The Studio Oda Pälmke is located at the director’s villa of a former pumping station in Berlin, which today serves as atelier complex for the artist Jonathan Meese. Such productive neighboring is delightful and inspiring.

What does your desk/working space look like?

The studio is a peaceful and efficient precision workshop.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

I studied architecture at the Technische Universität and at the Hochschule der Künste in West Berlin, formative years in the city of fragments. As a project manager in the young firm Kollhoff and Timmermann I planned and built a social housing-residential building.

At the same time, I taught Housing Design as a research associate at the Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen, today Bauhaus Universität Weimar. This intensive time was like a postgraduate degree and the beginning of my work as a visiting professor for Architectural Design at EPFL Lausanne, HfBK Hamburg, TU Dortmund, BTU Cottbus, and full professor at TU Kaiserslautern (fatuk).

What are your experiences founding your studio in Berlin?

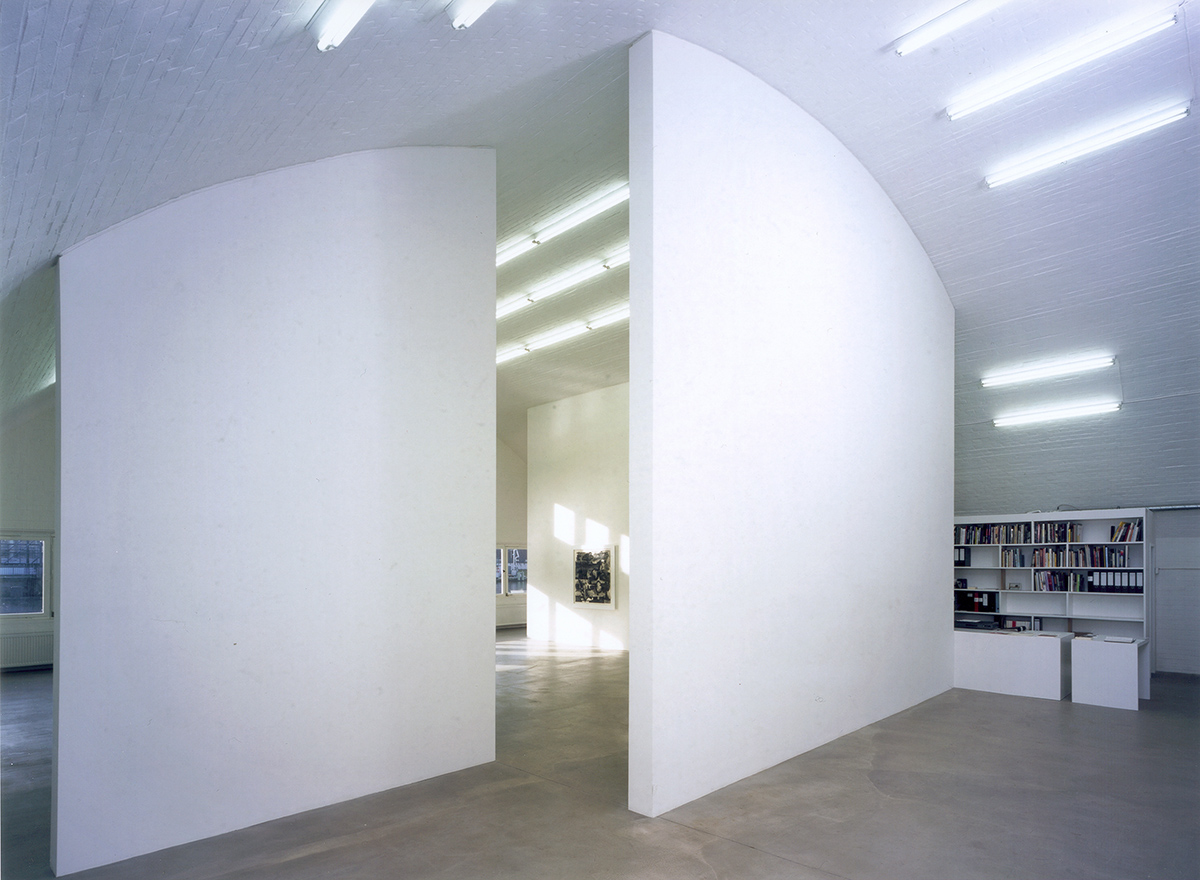

I treated my visiting professorships like architectonic projects. As an architect, I understand teaching as constructing, and I design a task or a publication like a building. In addition, teaching always co-financed my own „non-profit” studio, so I could design and realize artistic, uncompromising architectural projects, for a while in cooperation with my friends Tobias Engelschall and Etienne Descloux. The first decisive construction was the Gallery Atle Gerhardsen, a small project with great resonance. Since then, a continuous series of mostly private assignments has resulted of its own accord.

Gallery Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin © Jens Ziehe,

Tobias Engelschall und Oda Pälmke Architekten in Projektgemeinschaft

How is the context of Berlin influencing your work?

Here in Berlin live my ideal clients: often creative art and culture workers themselves, interested in an architectural discourse and in an artistic design with a high conceptual approach, which is independent from budget and volume. Most projects are modifications of existing buildings, and the concept develops in process, often on site. Sometimes I propose to keep places as they are and to just look at them anew. I do not produce renderings but manifold readable, abstract architectural drawings, which, as paintings, transmit idea and ambition but leave the real result open. A narrative, formally free concept is tolerant and understands disruptions as enrichments. This only works with really open-minded clients, the longer the better of course. Ulrich Brinkmann described in “Bauwelt” this working style as “design principle of total trust / Entwurfsprinzip Totalvertrauen”.

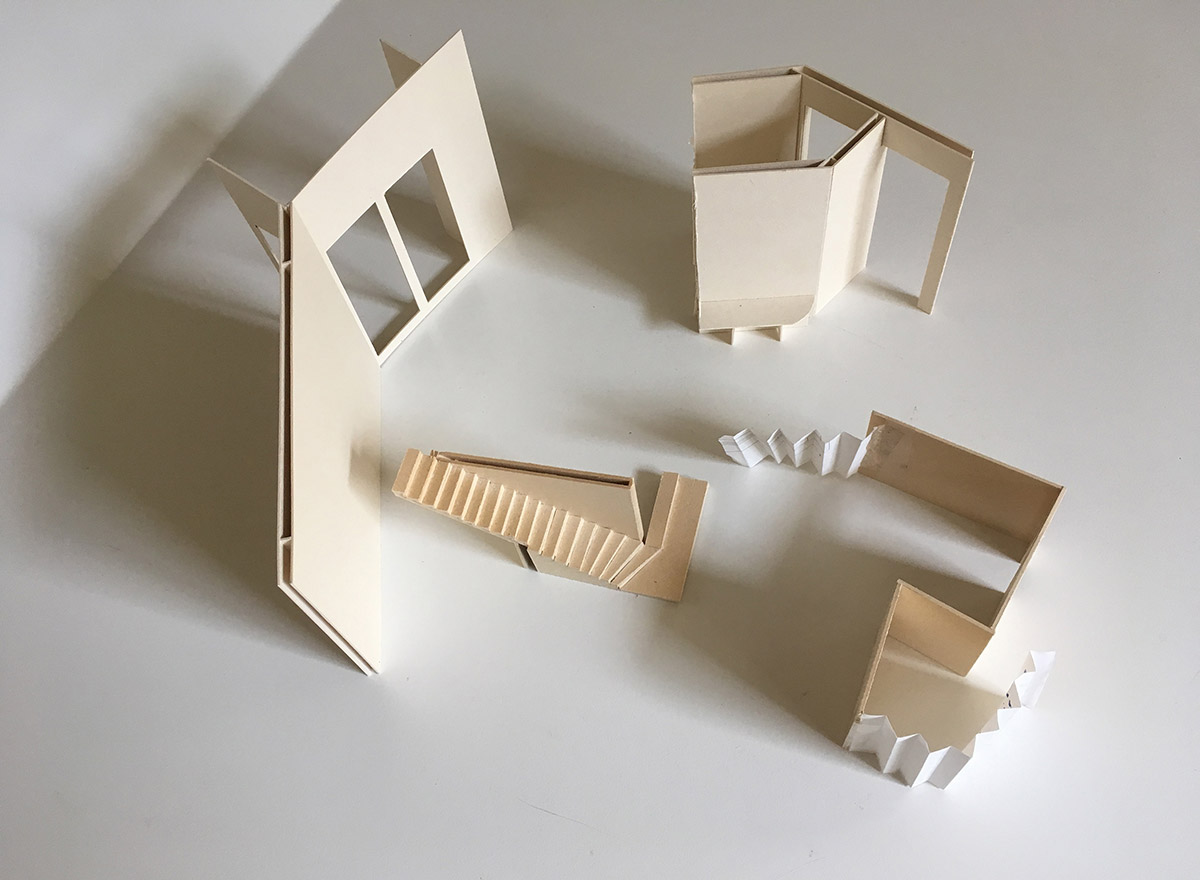

The Post Republic, Berlin © Stefan Maria Rother

The projects differ in formal aspects but share the similarity and history of one family. While they individually adapt to and thus elevate their particular environment – what named Florian Heilmeyer in „uncubemagazine“ as „invisible architecture“– in my eyes they complement each other by repeating moments (object symbols) to a work constantly expanding and changing. I honor this quality as the coherence of the fragmentary. As one can see from the chosen projects – I am not interested in proportionality with regard to size, only with regard to the conception, the narrative of a project.

Fragments of Models - Object symbols © Oda Pälmke

Your thoughts on Architecture and Society?

In my own work, in society and in architecture I seek a balanced relation between concept and texture, ideal and reality, individual and collective, object and context. That’s why I plead for a tolerant and undogmatic production of architecture and reception of society by us experts.

Residence Beuthstrasse, Berlin © Maximilian Meisse

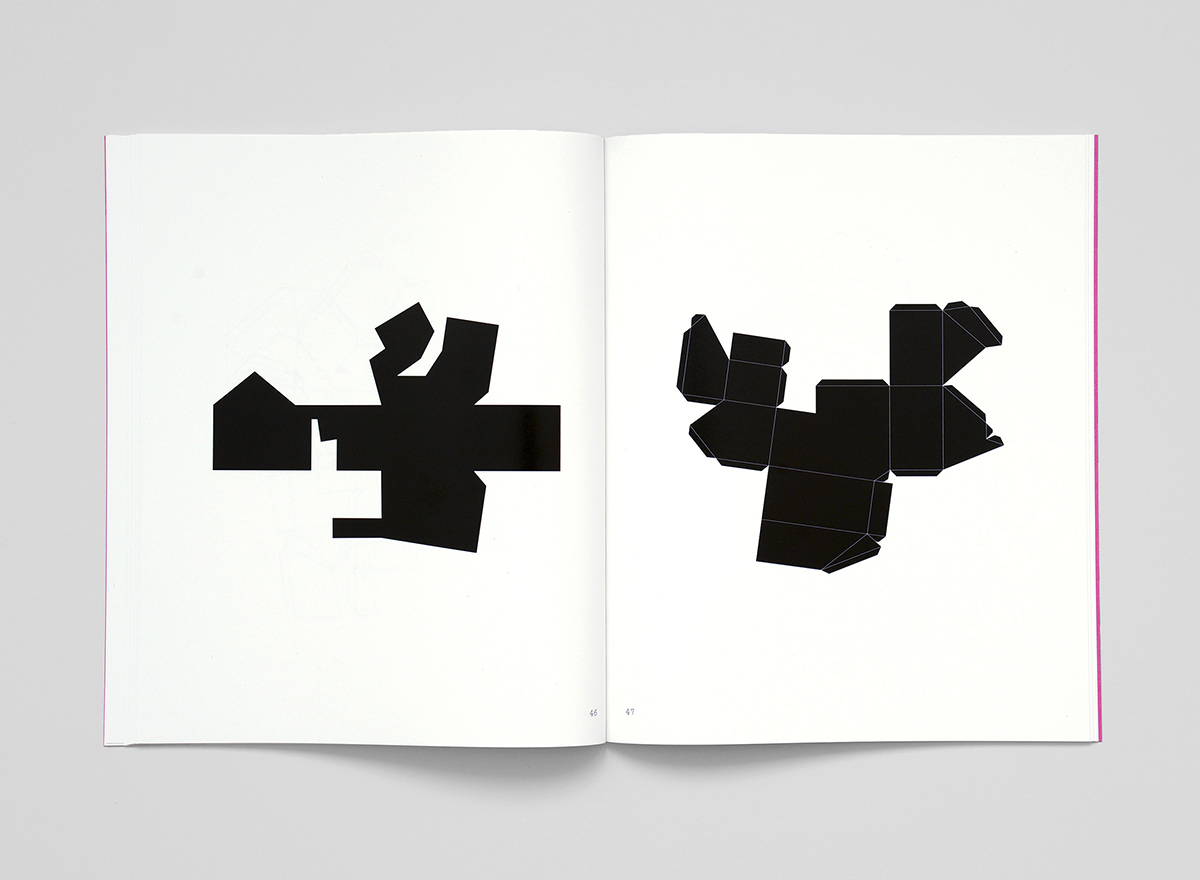

In my books I sorted buildings that are usually not called architecture by typological-morphological criteria in order to make them visible “like that”. It intrigued me to declare plain buildings to be (architectonic) objects by taking them out of their context. Anh-Linh Ngo called that the “fictionalization of the existing / Fiktionalisierung des Bestehenden” (in Arch+). If one observes “beauty” (venustas) formally free and “loving idea” and “theme” of something built seriously, the classic sense of architecture might be enhanced. This would also be, with regard to societal acceptance and, therefore, relevance, “quite good”.

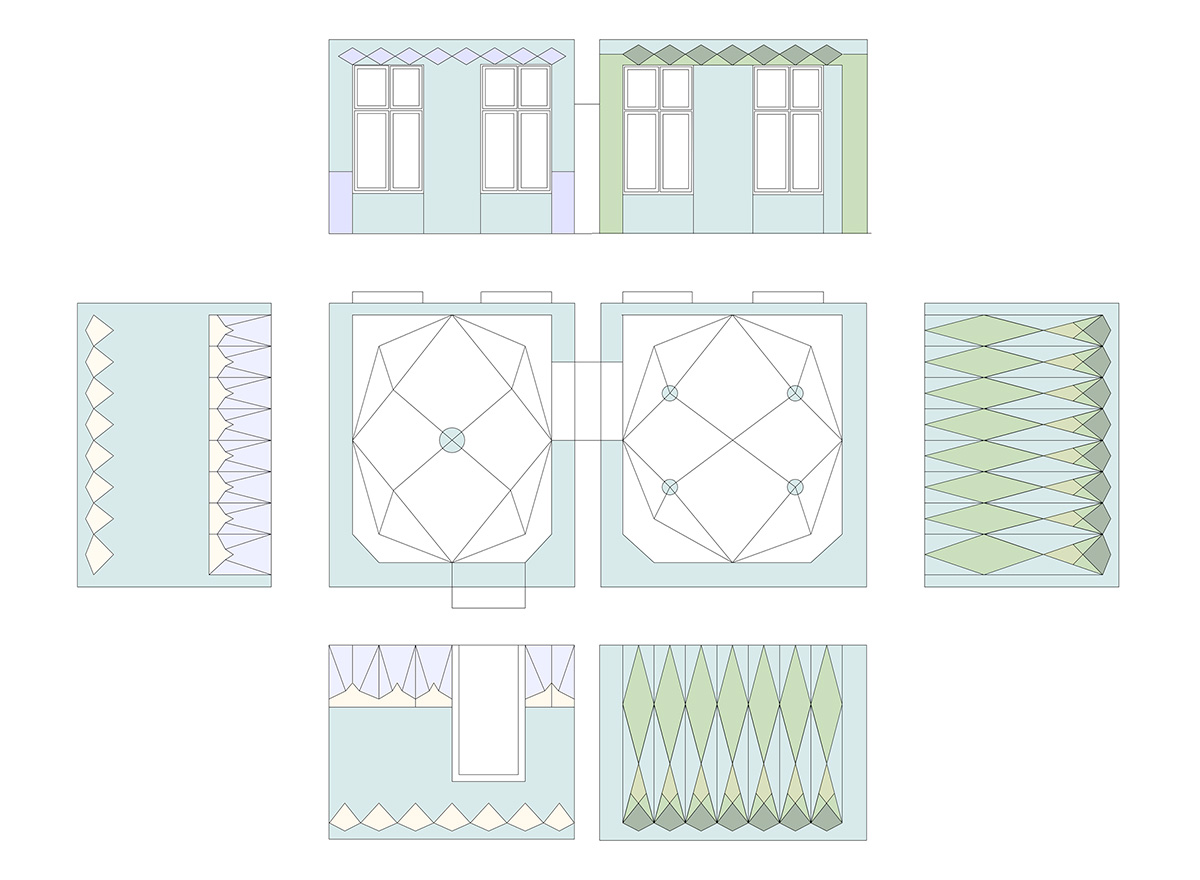

Oda Pälmke, GANZ GUT / Quite good houses and FACADES, jovis Verlag, Berlin © Oda Pälmke

What is your approach on teaching architecture?

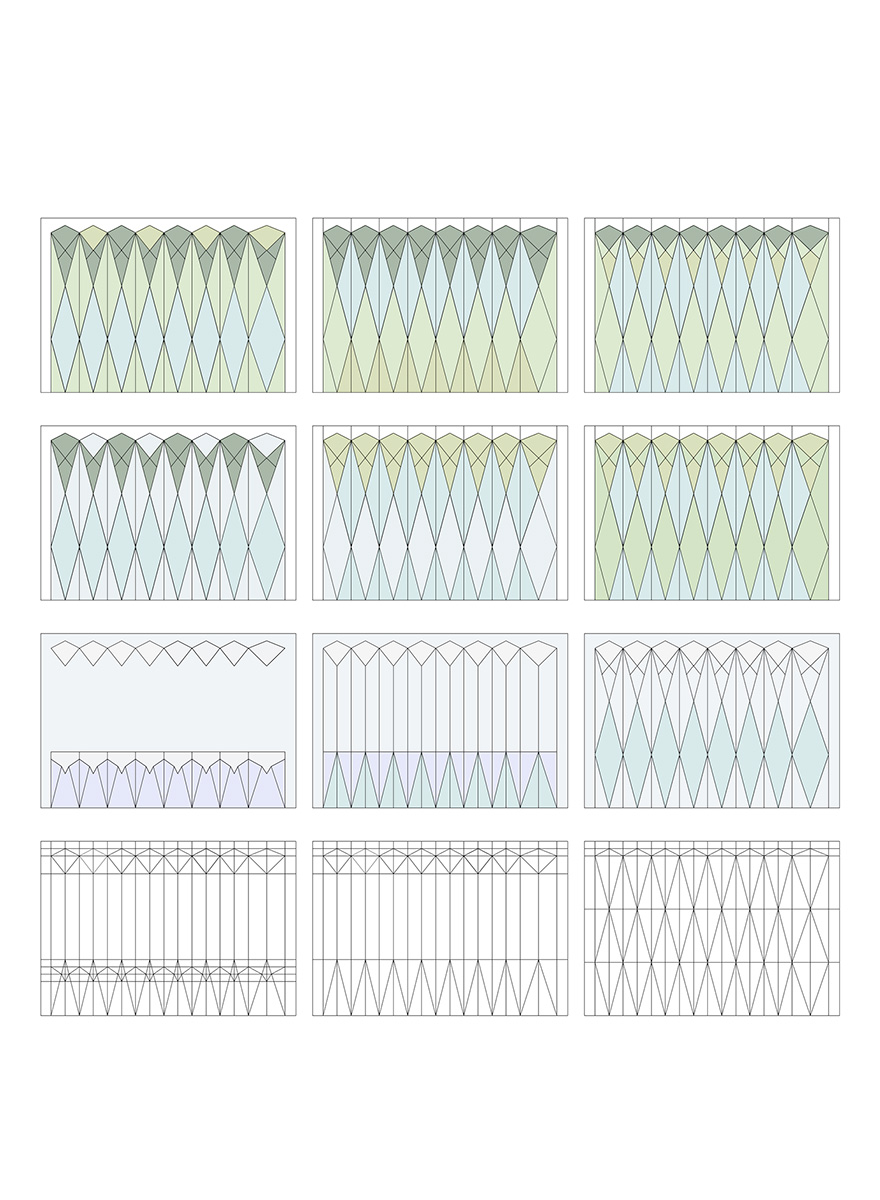

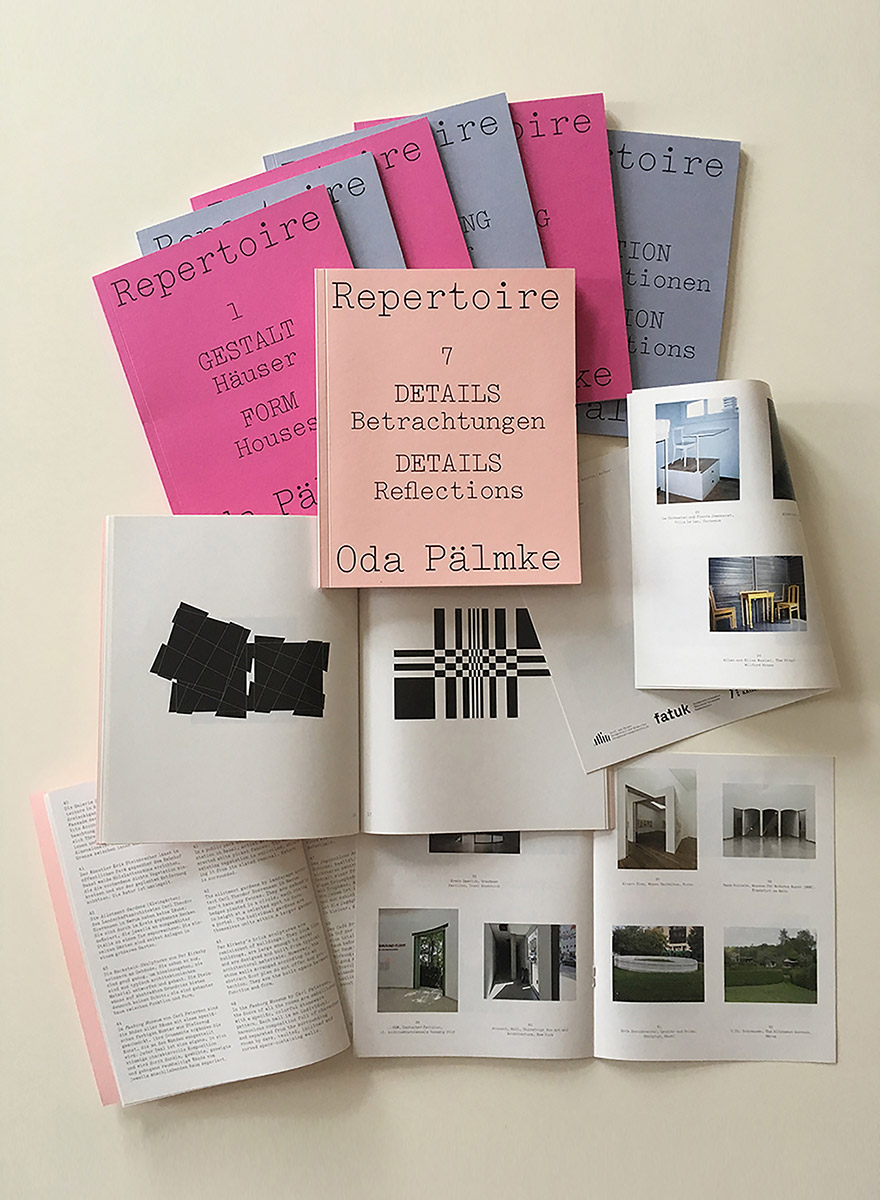

In his foreword to my book “Haus Ideal, the Making Of”, a publication accompanying my guest professorship in Cottbus, Christopher Dell named it a “Teaching as an Architectural Work / Lehre die zum Werk wird”. In “Haus Ideal” I understood my students’ drafts in each state as relevant productions, the process of composing is as worthy as the result. As an architect, of course, I try to give teaching a shape. My recent publication “Repertoire, nos 1-7” (aboutbooks.ch) is a research on the sustainability of form. In books 1–6, my students and I precisely drew phenomenological findings in the architectonic environment. “We drew the undrawn” in order to become aware of the multitude of shapes surrounding us and to practice designing (find the shape) by knowledge and transformation of the existing.Book 7 is a reflection on details; it deals with the proportionateness of an idea.

Book launch at the ARCH+ salon, 2020, Repertoire 7, Oda Pälmke, fatuk, TU Kaiserslautern, aboutbooks.ch © Oda Pälmke

At my chair for “Spatial and Architectural Design” I try to convey the importance of the idea–from the first thought to the pure concept. In terms of content I transmit (so I hope and try) formal freedom and precision of thought. Practically, I teach the art of reducing, reworking, simplifying and refining–the essence of architecture.

Repertoire 1 Gestalt-Form, Oda Pälmke, fatuk,

TU Kaiserslautern, aboutbooks.ch © Bruno Margreth

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

Architecture frames our lives, makes us feel good, look good, behave good.

Mirrors of Repertoire, book-launch at ARCHITEKTUR GALERIE BERLIN SATELLIT © Maximilian Meisse

Which material fascinates you (always)?

I use non-refined materials, wood, stone, color, glass, and try to refine them into something new. Mirrors expand a space. Looking into them one sees the world as it likes to be seen.

Project

The Secret Library

Berlin

2020

The Secret Library has just been finished. The installation turns the room into an object, that’s what I’m after here, but the library is of course absolutely functional and most efficient, too. All dimensions are derived from the proportions of the rooms and books found, they emerged in principle from drawn calculations (logic). The tailored low-budget haute-couture sheathing made of wood and fabric appears in colors by artist Gudny Gudmundsdottir (magic). The artistic harmonies and dissonances transform the rooms into a wintry, clear ice lagoon or a summery, cheerful dacha, depending on your mood. The table has the shape of an ellipse, as the skylight in Aby Warburg’s library, and thus refers through various intellectual levels to the freedom of thought.

Websites: www.odapaelmke.de, www.raumgestaltundentwerfen.de, www.odapaelmke.com

Instagram: @odapaelmke

Facebook: @odapaelmke

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 07/2020