22/016

pihlmann architects

Architecture Office

Copenhagen

«Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces.»

«Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces.»

«Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces.»

«Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces.»

«Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

Thank you very much for letting me tell a little about me, the office and what we have been up to lately. I’m Søren Pihlmann, founder of pihlmann architects. We are a quite young (if I do say so myself) Copenhagen-based office. Today, we are around ten trained architects of different nationalities. We’re situated on Refshaleøen – meaning something like Fox Tail Island due to its shape seen from above – an artificial island heavily impacted by its industrial heritage, but also a place which is undergoing quite a massive urban transformation recently. It’s close to the city center, but you still have that special feeling of leaving the city behind, when you bike out here. Until recently, it was a hidden gem. Now it’s just a gem – at least when the sun is shining.

Our office space is the former casting workshop of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, where I began my studies in 2009 and spent endless hours until graduating in 2014. So physically I haven’t moved very far since then, but I like to believe that I’ve come far mentally. That being said, we try to maintain the best which architecture school has to offer (which is an incredible lot) and bring it into the way we think and create architecture in our office. Although the circumstances aren’t quite the same as they are at school – we are very aware of that – we’re shaping ideas and experiment a lot like we did back then. It’s essential to the way we like to work, and how we like to bring our projects to life. Perhaps it’s due to the fact that, aside from a semester as an intern at Danish office Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects almost ten years ago, I haven’t been working at the big offices unlike many of my colleagues. We might never know.

Portrait Søren Pihlmann – © Monica Skovgaard

After practicing architecture together with Kim Lenschow (lenschow & pihlmann) for some years, you recently founded pihlmann. What are your experiences founding your own office?

Of course, the circumstances are not quite the same as when Kim and I started lenschow & pihlmann right after we graduated, but my approach to architecture hasn’t changed radically since then. So, it’s not a breakaway from our former practice and way of doing things, it has rather been a natural extension of the solid foundation we built and which pihlmann architects still relies on.

So, my experience with founding pihlmann architects has been overwhelmingly good, but I’m well aware that is hasn’t been like starting all over, not at all. Furthermore, we have been so lucky (and hardworking) to start out by winning some interesting projects of great importance for us and our further development. These projects are greater in scale than what we have been working with before and I believe this has given us a unique chance to prove and express our architectural ideas even clearer – and hopefully also to reach an even greater audience, giving people the possibility to experience our architecture by themselves. I like to believe that many people with an architectural interest in Denmark may know who we are and have seen images of our projects, but I’m quite sure that only a few of them have actually been inside one of our projects. This is about to change which is a great privilege. And responsibility.

These new bigger projects have led to our office growing significantly in only a short time, so we have been busy from day one. It’s different than when Kim and I started lenschow & pihlmann at the age of 27. Today, I’m responsible not only for a group of employees but also for several collaborators and partners who rely on us and believe in us. The combination of bigger projects and standing on my own two feet has caused glimpses of nervousness, but I use this as motivation: I try to be even more clear and precise about what we want to achieve, why we want it and how we get there. Both internally in our everyday discussions, but also how we communicate our architectural ambitions to our surroundings. So even though this new beginning hasn’t been a turnaround of my architectural visions, it has been the perfect occasion for looking at them from a bird’s-eye perspective and figuring out how to make them become reality. I believe this has strengthened us and hopefully our future projects will reflect this.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your projects? What meaning does location have to you overall?

Copenhagen has been a great source of inspiration (and concern) in terms of how we see European cities develop, but we are just starting to deal with it in our own work. Our projects have been spread over the country, but they’ve been mainly outside the bigger cities. This has changed dramatically lately, currently we have three construction sites in Copenhagen.

On a practical level, this has changed a couple of things; we are experiencing very much how our office has grown out of its own walls and we’re spending a lot of our working hours around town, both on-site and at various cafés or the like. For this exact matter Copenhagen is amazing (and the bureaucracy a little less amazing…), and the many talented and visionary people working here are inspiring and helpful. I think the architecture scene is growing, but mostly when it comes to talking about architecture. The scene for creating architecture has unfortunately been narrowing in for quite long. It is very difficult for even very talented offices to have something built, and there are very few open competitions left where you can break the barriers. Not so long ago, I read Dorte Mandrup stating that she is glad that she didn’t have to establish her office today. If it continues like this, I’m afraid we might lose a lot of talent. But there’s still hope; just recently, The Danish Association of Architects and The Dreyer Foundation launched an initiative called Projekt START to boost the possibilities for new offices to establish themselves. I cross my finger that this will be the beginning of new horizons for young offices.

Coming back to our projects in Copenhagen: It don’t think they made me change my overall impression of the city. But I’ve learned a lot about the neighbourhoods and communities where our projects are. I get very connected to them. I like the idea that our architecture is just as connected to their context as I get to it, but these contextual connections reveal themselves in various ways. Location is just one of them. Context is much more than location; climate change is also context. Having said that, we always take the location into account – both demographically, programmatically, historically, aesthetically and so on – and while location might be the Alpha and Omega in one project, the reuse of a suspended acoustic ceiling tile can be of greater importance in another. We have some approaches which we try to unfold within every project; then the circumstances decide how they materialize.

Process, Art Hub Copenhagen

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

The unedited truth on a sunny day in April…

What is the essence of architecture for you personally/for you as a group?

Architecture should give more than it takes. And to do so, you must really try. When I look around, I see way too many buildings where it is obvious that no one has put a real effort in the creation of it. It’s such a waste of space, resources, time and creativity... Today, it is way too easy to build something without anyone using any effort and then wrap it in generic surfaces. I am quite sure this wasn’t possible back in the day.

So, let’s at least demystify these architectural deceptions a bit, scratch their surfaces and reveal what they consist of. I don’t think any layperson has a clue about what modern houses are built and what they consist of behind the gypsum boards – even though people spend most of their lives inside of them. Let’s endeavor to consciously change this.

We contributed to the anthology ‘con-nect-ed-ness – An Incomplete Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene’ (2020) published in connection with the exhibition in the Danish Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021. Our contribution Home Minus 12.5 mm sheds a (self)critical light on contemporary architecture. Three 1:6 scale models depict spaces from some of our built projects. The models are decorated with furniture, plants, and everyday objects, but finished with the standard 12.5 mm layer of the plasterboard removed to expose the underlying components. The models expose the disjoint between the perceived architecture and the actual built conditions. We want our architecture to tell stories instead of hiding them, and this is a theoretical example of looking at our own projects with a contemplative view.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

Quite a lot needs to change! But that’s not only in the field of architecture. Architecture is so closely related to everything that’s happening around us in terms of climate change, resource scarcity, migration flows, nationalist movements, biodiversity loss, earth ethics, imperialism, power structures just to name a few related matters, which threaten – or have already massively impacted – societies all over the world. It’s all connected, and architecture will have to change according to the bigger picture.

So, what can we as architects do about it? Rebel? Perhaps. The least we can do, is to make a conscious decision to reflect on why we are doing the things we are doing and what we want to achieve. If the answer is fortune and fame, we’re on the wrong track. But I do understand that people tend to think this way. The competition amongst architectural offices is tough, which too often have led to undesirable consequences. That’s why I think it’s important that we become better at collaborating with other professions and communicating our visions to the everyday person on the street. Too often the lowest common denominator has decided architectural outcomes, because we haven’t been good enough at conveying the importance of architectural quality.

If we look at how rapidly things have changed over the last 30 years, I find it hard to believe that one can make realistic assumptions on the world anno 2050. I hope that we have built sustainable societies, but I have a feeling that our idea of the word sustainability will be quite different in 2050 than it is today. Or at least that the idea about acting and living sustainable will be different.

Regarding actions, we try to challenge the general impression of architectural significance; to pursue value within the seemingly valueless. We believe that this is one of the most important steps towards an architecture which does not repeat the mistakes of modernism, which has laid the foundation for contemporary western architecture. We try to go against the supposed simplicity of the modernist house, which relies on ideas of unlimited possibilities and freedom from all ties that bind. At best this simplicity is an illusion. At worst, it is a fraud.

We aim to expose (connections) rather than conceal. If we, as humankind, in 2050 have acknowledged that we are intimately connected to earth and are dependent on it, I think it’s close to my utopia. I would very much like to see how this acknowledgement will reflect our view on (not only) architectural value. I think it will change radically.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

I believe it would be a mistake to recommend one specific skill. Except if persistence is a skill? Everyone should find their own way, and it wouldn’t make any sense to educate an army of BIM-experts, just to give an example. Young architects should search for something which drives them and try to explore the essence of it. It will be an endless pursuit, as you will meet all sorts of obstacles along the way. But due to this endlessness, it will also become an unlimited source of inspiration which can lead your way.

Ever since architecture school, I’ve always been very interested in exploring all sorts of materials, their varying materiality and qualities, the assemblage of them. I still am, and I believe that has paved my architectural way. But I’m well aware that it’s not the only way to make a living within the field of architecture. Luckily there are so many others.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now?

There are many architects having very interesting things going on. Just take a look at your recent interviews, there are so many talented people and I celebrate everyone taking their time to share their work and thoughts.

Aside from architectural inspiration, I often tend to seek inspiration in the fields of art and literature, especially by artists and authors who have an interest in science. We need to establish new languages to become aware of the circumstances we find ourselves in. A language of intimacy which can make abstract as well as ignore matters that are emotionally tangible and visible to us. Here, we as architects can learn a lot from other artistic professions (as well as other fields in general).

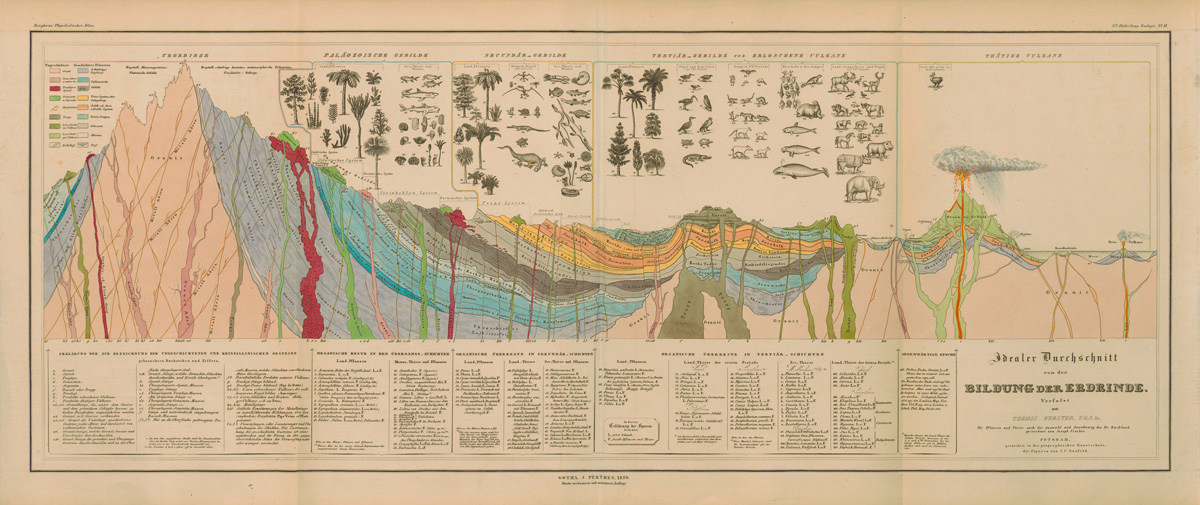

I come to think of collectives as ARIEL Feminisms and Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, artists as Studio ThinkingHand, Eliyah Mesayer and Rune Bosse, writers such as Andri Snær Magnason, Astrida Neimanis as well as geologist Minik Rosing and the always relevant polymath Alexander von Humboldt just to mention some of those whose work have inspired me in different ways.

Project 1

House on Fanø

2020

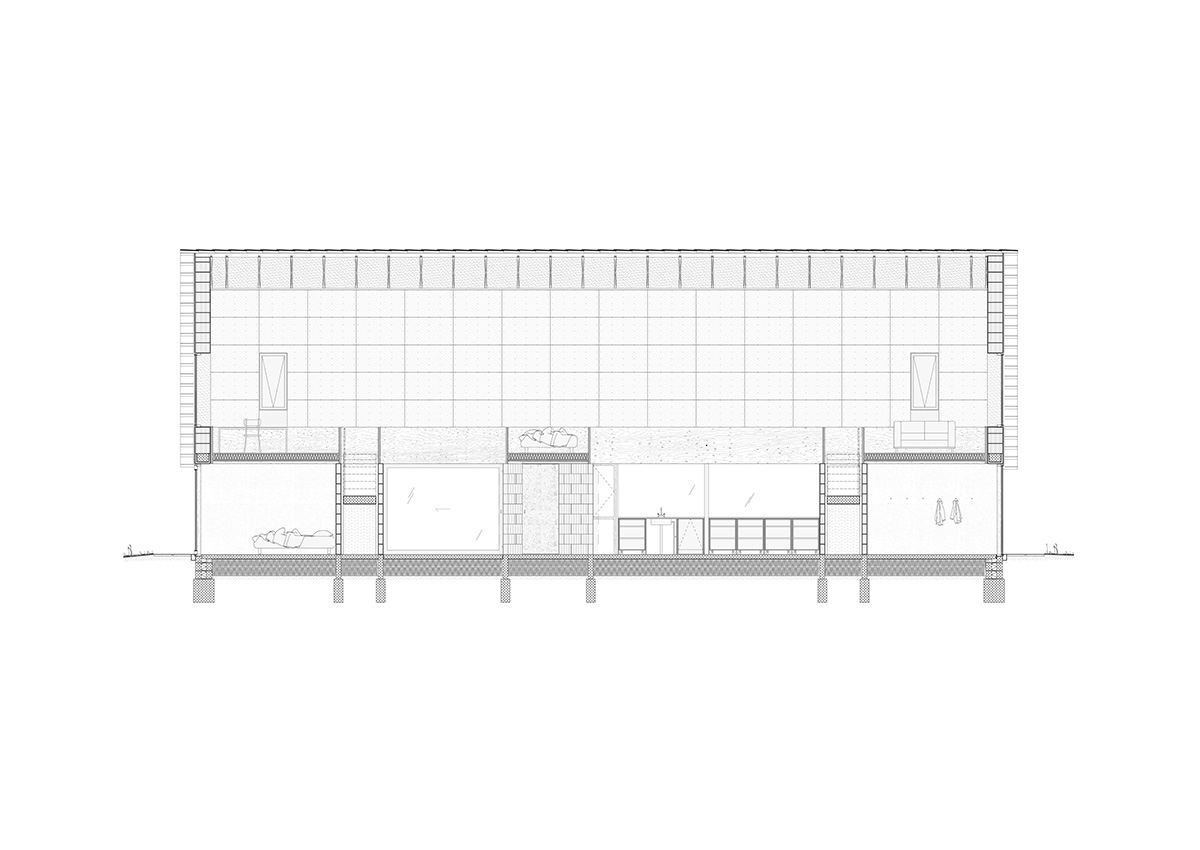

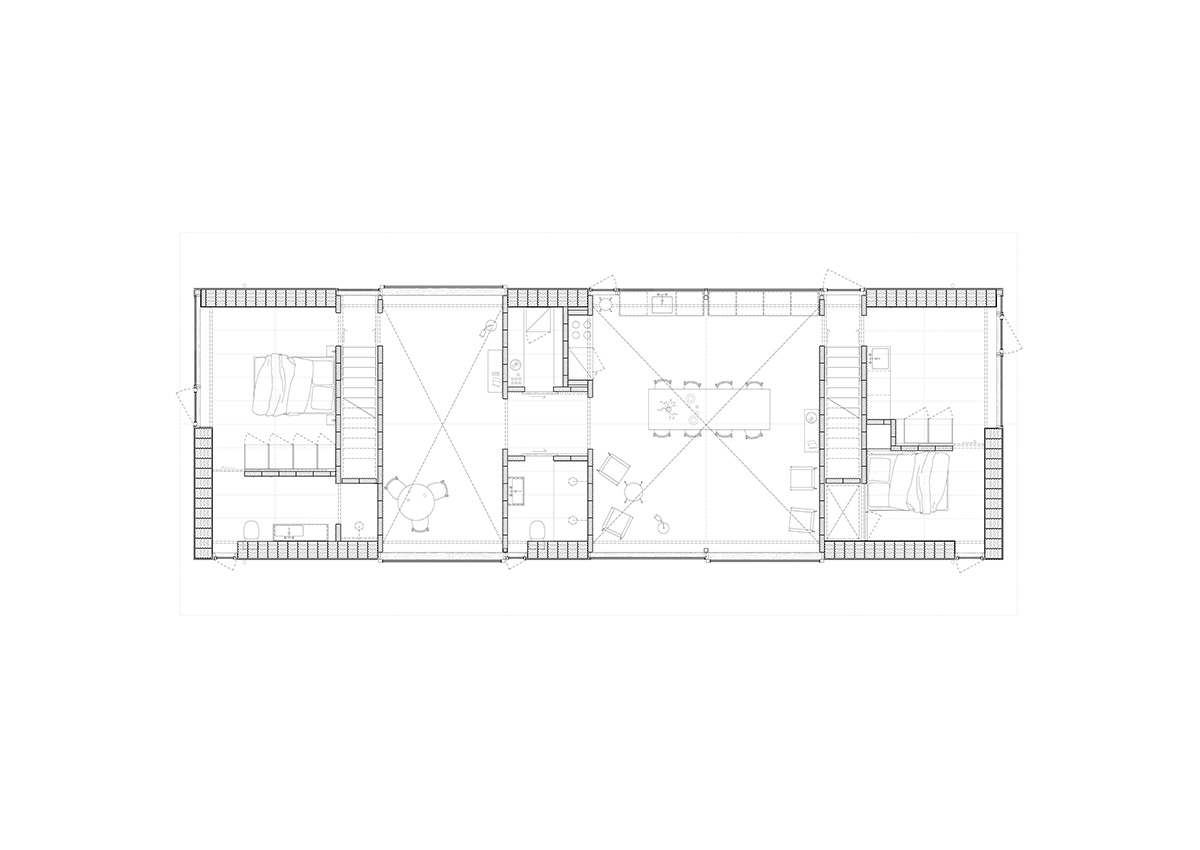

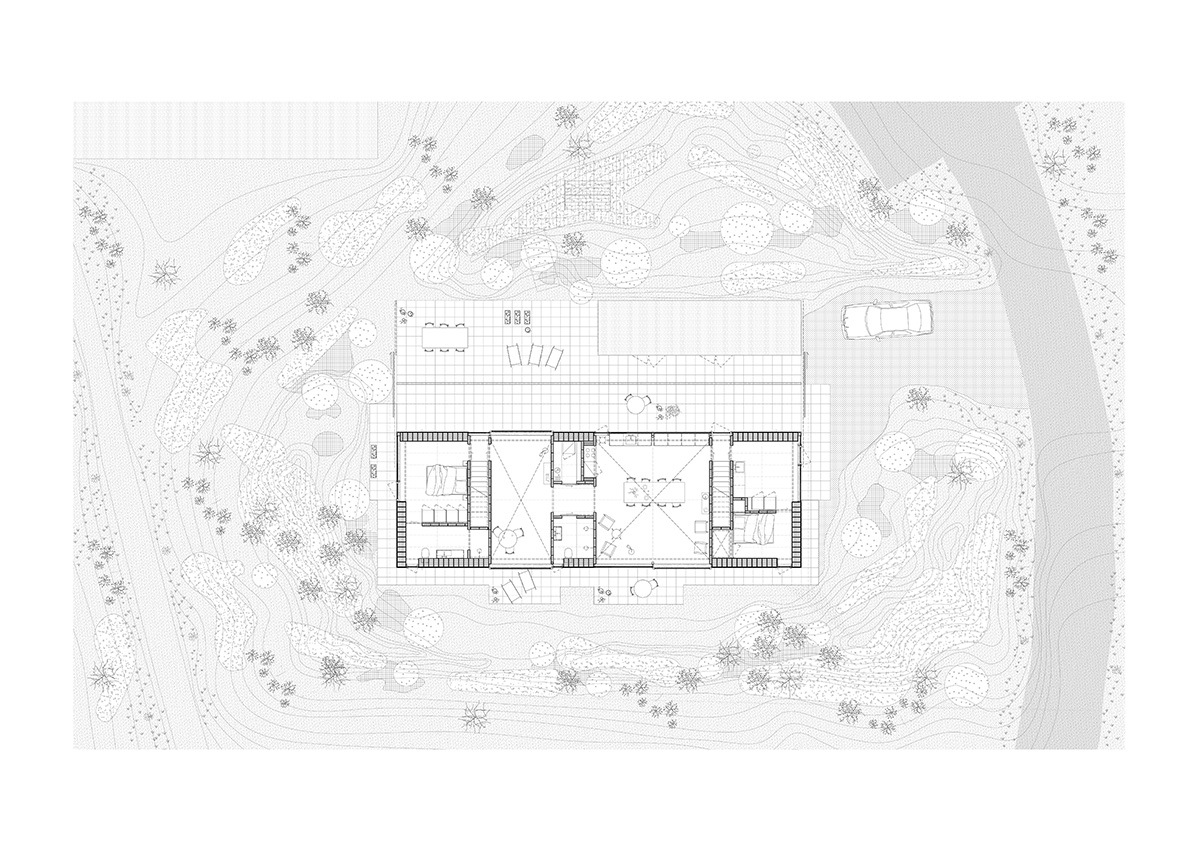

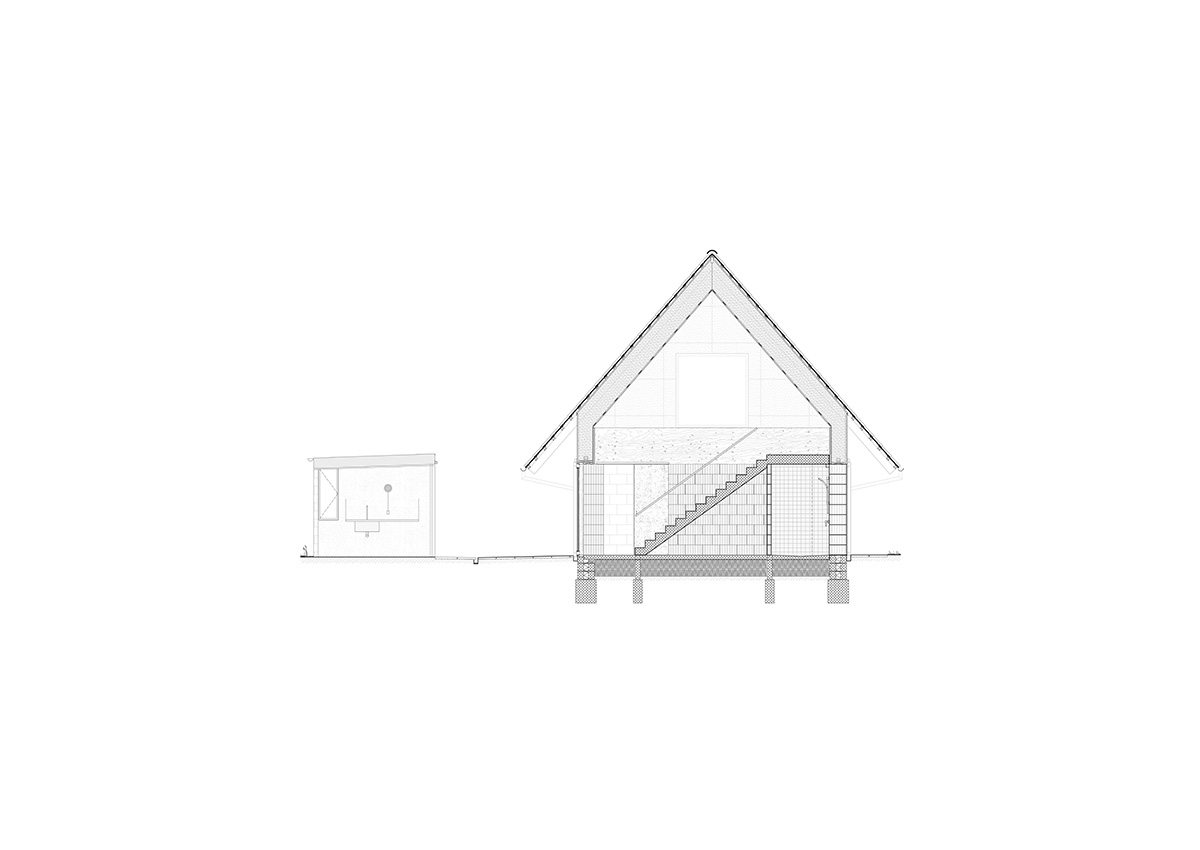

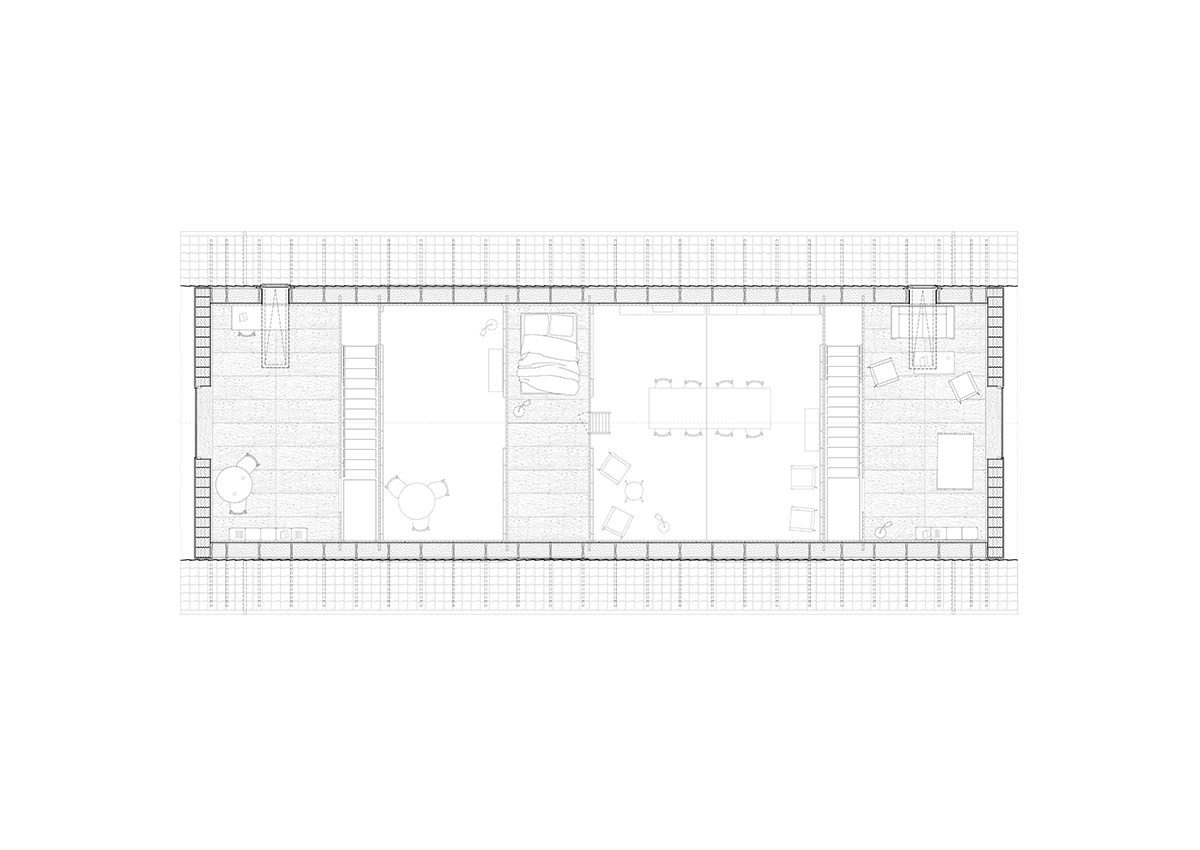

With the Wadden Sea coastline in the front, landscapes of heather and pine in the back and the Port of Esbjerg on the horizon, lies House on Fanø. It follows a local time-honoured tradition for solid longhouses as the island’s notoriously harsh wind has called for buildings based on robustness and simplicity.

Traditionally, barn and habitation were placed under one continuous roof, due to Fanø’s rough weather. The houses were built by sailors and farmers in robust, local materials, and they were oriented from east to west to protect from the west wind. Today, you still see the characteristic longhouses all over the island. House on Fanø interprets basic elements from the traditional longhouse and rewrites it within a contemporary construction practice focusing on the local identity, a simple structure and materials characterized by sensory qualities.

The structural clarity and simple composition spotlight the inherent qualities of the building components; the varying hue of clay blocks, the natural patterns of plywood, and the coarse structure of terracotta tone render. Each element bears its own logic, materiality and function, and the montage is rational. It backs the ambition of creating a simple architecture that exposes the principal elements, letting them be sensed through modest but textural materials. When components are separated and their embedded rationality is utilized, excess layers can be peeled away.

This contributes to a building that remains stable over time and supports a resilient construction practice. Thus, House on Fanø incorporates itself within a local tradition and reinterprets it in a contemporary, sustainable manner based on the embedded potentials of the materials.

Project: House on Fanø

Collaboration: Office Kim Lenschow

Location: Fanø | Year: 2020 | Size: 198 sqm

Photography: Hampus Berndtson

Project 2

Art Hub

Copenhagen

2021

Since 2019, Art Hub Copenhagen has been based in Kødbyen, the Copenhagen Meatpacking District. Within a couple of years, it will move to a new location. This temporary perspective is a premise which is turned into the general dogma: Every element must be reused. Nothing is discarded but rather revitalized through the alteration of function and appearance.

The dogma is rooted in the indisputable fact that today’s construction industry emits excessive amounts of greenhouse gases. If we are to achieve the climate targets – which we are fundamentally dependent on – it requires a radical transformation of the way we think and create architecture. Therefore, this project is developed as both materialized architecture and as a case study. It explores how to enhance architectural value through temporality and reduction of resource consumption.

By rethinking and reusing the elements added over time, the space is redefined based on an interpretation of the genuine atmosphere and spatial composition. No layers are added, instead the existing ones are peeled away, leaving the distinctive spirit of the space exposed.

Suspended ceiling tiles, known from various generic office spaces, have been dismantled and redefined. The slender aluminum profiles are left as a coarse-mesh filter, while the white tiles are reorganized into flexible, suspended folding walls. They hang as staged elements emphasizing the varying hue and intensity of the light, drawing references to both Kødbyen’s history and the surrounding facades.

The transformation of Art Hub Copenhagen points towards a general path for how recycling can be rethought in architecture. When resources are not consumed but regenerated into value-creating elements, recycling is not a necessary evil but the very catalyst of form and intention. Thus, this project operates sustainably on two intertwining levels: conservation of both resources and Kødbyen’s distinctive character.

Project: Art Hub Copenhagen

Collaboration: Archival Studies

Location: Copenhagen | Year: 2021 | Size: 200 sqm

Photographer: Hampus Berndtson

Website: pihlmann.dk

Instagram: @pihlmann

Photo Credits: © pihlmann architects (unless stated otherwise)

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 06/2022