19/046

precht

Creative Studio

Austria

«We should rather learn how to present our visions to non-architects.»

«We should rather learn how to present our visions to non-architects.»

«We should rather learn how to present our visions to non-architects.»

«We should rather learn how to present our visions to non-architects.»

Please, introduce yourself and your Studio…

Hi, I am Chris a young architect from Austria. But more importantly, I am the husband of my wife Fei. Together we founded our small studio Precht in the Austrian mountains.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

I found my way into architecture rather accidentally—the decision was reckless after all. According to my opinion the best decisions are the ones made quickly, following your heart, because the brain can be a real pain in the ass from time to time. Anyway, I fell in love with architecture immediately. Before I started to fall for architecture, I studied 3D-software and worked on animated movies. After becoming more proficient with the software, I looked for a field of activity combining those tools; architecture felt like the obvious way to go. Instead of human characters, I started to model buildings. Thinking through it now, I have to say the tasks are actually very similar. Because a good building needs to be a character by itself in my opinion.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project?

I was looking forward to doing my diploma project during all the years of studying. Taking a full year for a project, working on nothing but one topic sounded wonderful. But time went quicker than I anticipated, of course. During my last year at university, my wife Fei and I won our first competition and founded Penda together with our friend Dayong. The project Soundwave suddenly turned from a competition design into a construction project and things became serious: Setting up a business, paying salaries, going to a construction site and meeting clients—this process hit us basically overnight. My diploma transformed into a side-project meanwhile. But it still turned out as a decent project. I was working on a library for the future. Considering the internet, Amazon and e-book readers like Amazon’s Kindle—that enable you to access basically any information anytime at your fingertip—a library is an interesting topic to think about. A typology that connected previous generations to the 'wide world' might serve as a typology that connects you to a local community in the future. I imagined a future library as a center for information and inspiration with a large communal park on top of the building that connects the neighborhood.

What are your experiences founding Precht and working as a self-employed architect?

As mentioned before, I already had experience in establishing a business before kicking of our current studio Precht. Founding this project with my wife was different, because all circumstances were different. We are not based in Beijing anymore, but living in the Austrian mountains now. Further, there was a change in my motivation and reason for working as an architect. What I learned during the past two years living in the countryside is that success is only matter of definition. While working as Penda success meant to me being able to grow my team, to work on bigger projects and to become famous. In those terms we did fairly well. But what no one told me was that architecture is not a scalable business. The concept of growth—hustling from one project to the next, meeting clients, writing contracts—doesn’t make sense to me any longer. There are so many opportunities out there, if you try to chase all of them you feel like a hamster running in circles after a while. This is why I learned to define success in a different way for myself. I don’t need to be a famous architect, nor a big or a rich one; I want to be a happy architect. This shift of mindset initiated us to move to the mountains, downsize and create a healthy work-life balance. We work now from the middle of nowhere, working on a couple of projects per year and couldn’t be any happier. Opportunities can easily turn into distractions. If you are not constantly surrounded by distractions, it is way easier to filter and recognize the real meaningful projects.

Why do you think the business of architecture is not scalable?

As Koolhaas put it, ‘We are in the business of uniqueness.’ Considering business, this is a stupid idea. If you design a small house, you need two architects in your team to take care of it. If you are in charge of designing an airport, you hire 30 architects. But your profit margin stays the same. In case your airport-project fails, you either need to fire the 30 architects or you need to hustle harder. Other creative industries, product designers for example, have a different business model. I wouldn’t say it’s easier to be a product designer, but if you are successful, you design one chair to sell it a million times. This is a scalable business.

How would you characterize the Austrian mountains as location for practicing architecture? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

I am not sure if the mountains influence our work, but we do certainly benefit from being in this surroundings. The mountains give us a sense of reality. As an architect you spend most of your time in a fictional world working on ideas, creating visions, thinking about the future. Living in the mountains is balancing this out. While hiking, climbing or ski-touring you need to be present in the here and now. Otherwise, you put yourself in danger. You need to be entirely connected to all your senses and emotions. You need to feel if a rock might break, recognize if the weather changes or hear if an avalanche descends. Those are the rare situations that enable us to experience nothing but reality. Have you ever tasted an apple in 3000 meters altitude? It’s the taste of reality and a great balance to daydreaming.

precht office building

precht office building

What does your desk/working space look like?

My desk embodies the process of finding a compromise between my messiness and the complaining of Fei about this never-ending condition.

What is the essence of architecture?

As corny as this answer might be: for me, the essence of architecture lies in creating a better future as well as in inspiring others to do so. This definition is pretty open, but this is exactly what makes the approach of architecture so beautiful. It may include a better future for the couple who wants you to design their small home or it may be the process of thinking about the future of our cities and how to improve them. Tasks an architect needs to handle and take care of today are incredibly diverse. This very fact creates a lot of niches for a younger generation to leave their marks.

Your architectural mentors?

If I had to name a person, I would say it is Gregor Hoheisel. He was leading the Beijing branch of Graft. Gregor is not only a great architect, but also a good boss. He taught me how to lead a team with passion and empathy; attributes, that are something rare in our industry. A good office climate is very important and at the same time hard to achieve. It always starts with the heads of a company. A good boss in my opinion is not the one winning lots of awards, but the one creating a good atmosphere for everyone to thrive and be creative. This skill is not taught at university, but I fortunately had the chance to learn it from Gregor.

If I had to name a book, I would say 'Sapiens' by Yuval Harari, that impressed me deeply. Harari opens up a wider perspective on who we are and what we are doing as human beings—this kind of looking at the world is very much needed. Our times are defined by a certain short time thinking and self-centrism. Further, I believe that architecture can create a broader perspective as well. Space can be a transmitter of culture, identity and tradition.

If I had to name a building, I’d select the Bamboo Buildings by Ibuku. Their works are natural, haptic, climate-appropriate, sensible and emotional. Everything that good architecture should be.

How do you communicate / present architecture?

Not being able to communicate architecture appropriately is one of the biggest weaknesses architects have. We as architects should play an important role in solving the challenges of our time. To only name a few: urbanization, the climate crisis, equality and migration. We are trained as strategic dreamers, able to combine long term visions with practical solutions, who combine business and creativity. But we fail to communicate this fact and rather hide behind an artistic profile of ourselves. Architecture shouldn’t be defined any longer by a formal approach, artistic styles or academic theories. The issues of our times are more serious than that. We need to find a way to communicate our values and positions regarding these issues. Currently, architects are involved approximately only in about 5-8 percentof all global building- and construction projects. Maybe the majority of people stopped listening to us, while we were only talking to ourselves.

What is your approach on teaching architecture? What do you want to pass on?

Continuing my thoughts from the question before, it's about time to stop inviting other architects to final crits. Maybe we should invite the parents instead. We don’t need to learn how to present our projects to other architects. Talking to other architects only creates a communication bubble, that is hard to get out of. we should rather learn how to present our visions to non-architects. Other architects won’t ever be our clients.

What advice would you give young architects who start working independently?

I’d recommend finding a way to build upon the passion you had as a student. Idealistic students leave university and after working for two years in our field, they lose interest. Which is weird, because you study for years to reach the level to be finally able to work and create. The motivation should increase, instead of decrease. Architecture is too beautiful to lose your passion over it. For us, this prospect of losing passion was the final trigger for us to move to Austria and restart with our new studio. Of course, that might not be a viable path for everyone, but in our case it worked out.

Your thoughts on Architecture and Society?

We are living in an age of technology. The 'smart city' is propagated as inevitable path of the future. That might be true, but at the same time we need to question the influence of technology on our daily life. In a smart city there might be more knowledge, more connected data and more intelligence available. We will know more, but I fear we will feel less.

We shouldn’t strive for a world that is driven by efficiency and perfection. We are wonderfully imperfect beings, the best things emerge while perfection takes a break. In a lot of companies, in order to make higher profits, everything is streamlined to be as efficient as possible. But to focus on efficiency only kills creativity. If we give up spontaneity for efficiency, we run the risk to create a world of plans and schedules.

In China exists a tendency now to bring the quality of the city to the countryside to prevent people from leaving their villages. Living in the countryside in Austria, I believe that we need to bring some qualities from the countryside to the cities. We might need more intelligence in cities, but at the same time we need more consciousness: trees and plants for example that connect us to our senses, feelings and emotions. Objects that connect us to reality, like the apple on 3000-meter altitude.

Project

The Farmhouse

For the last 2 years, our studio developed a modular building system that investigates the connection of people with their food and creates a building that connects architecture with agriculture.

Premiss

During the last 2 centuries we became disconnected from our food. For thousands of years, people, their food and cities were intertwined. The beginning of farming gave birth to our first permanent settlements and both grew, hand in hand, with the demand for more food and more liveable areas. With the industrial revolution this changed. Advances in transportation and preservation made it possible to deliver goods faster and store them longer. The process of growing food moved out of our sights and out of our minds.

Since then, agriculture and architecture battle for territory and resources. The need for growth and the greed for profitability brought our natural habitat to the brink of existence.The building and the agriculture sector are the two largest polluting industries and each day, 90% of the world’s population breathes polluted air. Both sectors became harmful to us. Obesity, diabetes, heart disease and lung cancer are an outcome of a one-sided diet and an unhealthy environment. But food and shelter are human needs and architects can rethink their relation. There is an opportunity to reconnect architecture and agriculture and change them to the betterment of both.

We think we miss this physical and mental connection with nature and this project could be a catalyst to reconnect ourselves with the life-cycle of our environment. Our motivation for ‘the Farmhouse’ is personal. 2 years ago we relocated our office from the centre of Beijing to the mountains of Austria. We live and work now off the grid and try to be as self-sufficient as somehow possible. We grow most of the food ourselves and get the rest from neighbouring farmers. We have now a very different relation to food. A tomato from your garden tastes different then the one shipped around the globe. We are aware that this life-style is not an option for everyone, so we try to develop projects, that brings food back to cities.

The Farm

In the next 50 years more food will be consumed than in the last 10.000 years combined and 80% will be eaten in cities. It is clear that we need to find an ecological alternative to our current food system. What and where we grow and eat. Topics like organic agriculture, clean meat, social sourcing and ‘farm to table’ will be key elements of this change. That means that our urban areas need to become part of an organic loop with the countryside to feed our population and provide food security for cities. If food is grown within the region, the supply chain and the use of packaging gets shortened. Stacked gardens reduce the need to convert forests, savannahs and mangroves and allows used farmland to naturally restore itself. Vertical farms can produce a higher ratio of crop per planted area.

The indoor climate of greenhouses protect the food against varying weather conditions and offers different eco- systems for different plants. Our Farmhouse runs on an organic life-cycle of byproducts inside the building, where one processes output is another processes input: Buildings create already a large amount of heat, which can be reused for plants like potatoes, nuts or beans to grow. A water-treatment system filters rain- and greywater, enriches it with nutrients and cycles it back to the greenhouses.

The food waste can be locally collected in the buildings basement, turned into compost and reused to grow more food. ‘This process of food production becomes visible,’ says Precht. ‘It reenters the centre of our cites and the centres of our minds. Food is an important part of our daily life and I see ‘the Farmhouse’ as an educational statement that it’s no longer a mystery where our food comes from and how it lands on our table.’

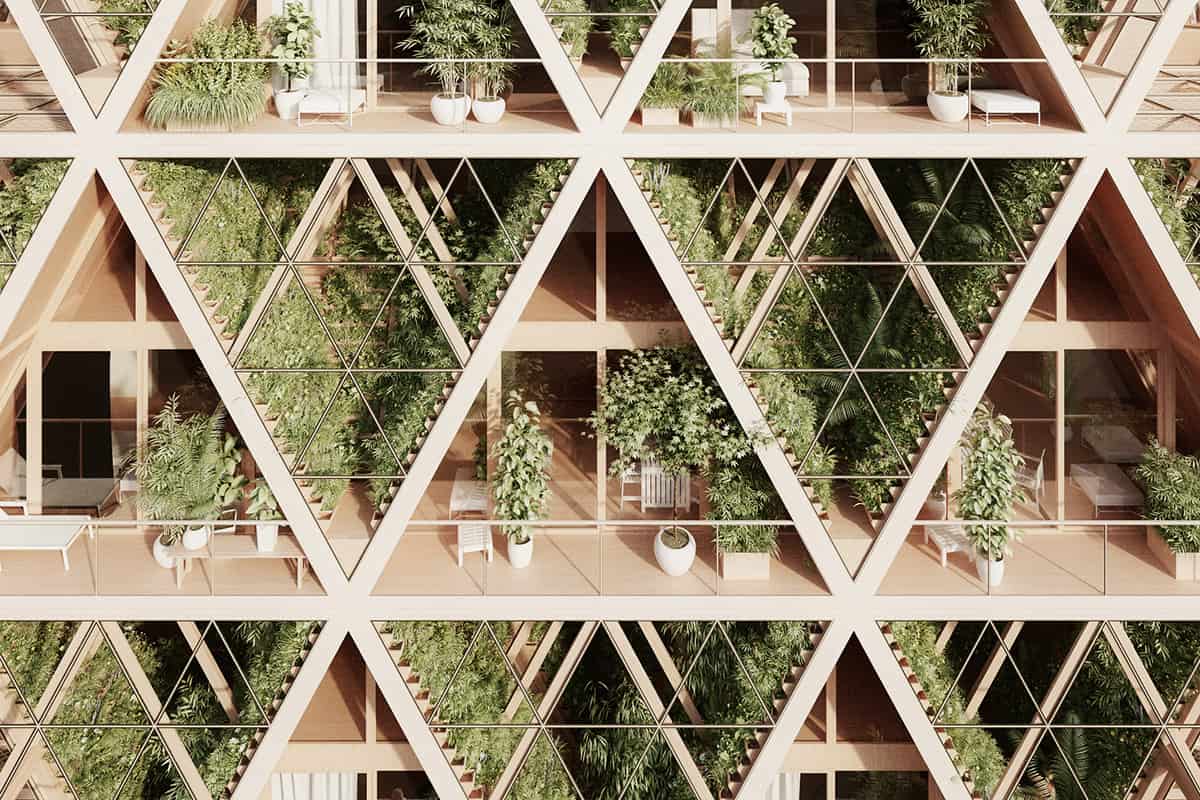

The House

The foundation of the Farmhouse is to encourage citizens to grow food locally, but it also continues this ecological aspect with its architecture. ‘In a way, we construct our farmland and we plant our building.’ Trees provide the main building material for the Farmhouse. Cross Laminated Timber panels are used to develop the modular system of structure, finishes and planters. Working with CLT has a lot of benefits. It is precise to fabricate, easy to transport and quick to install. Living with wood has also ecological benefits: Trees grow by a natural source of energy. The process that creates structural engineered wood products takes far less energy than steel, cement or concrete and produces fewer greenhouse gases during manufacturing.

Further, wood stores carbon in itself (approximately one tone per cubic meter) thus it has, compared to other building materials, a lighter overall environmental footprint. The Farmhouse consists of a fully modular building system, which is prefabricated offsite and flat- packed delivered by trucks. Prefabrication of a modular building kit shortens the time for construction and its affect on the surrounding.

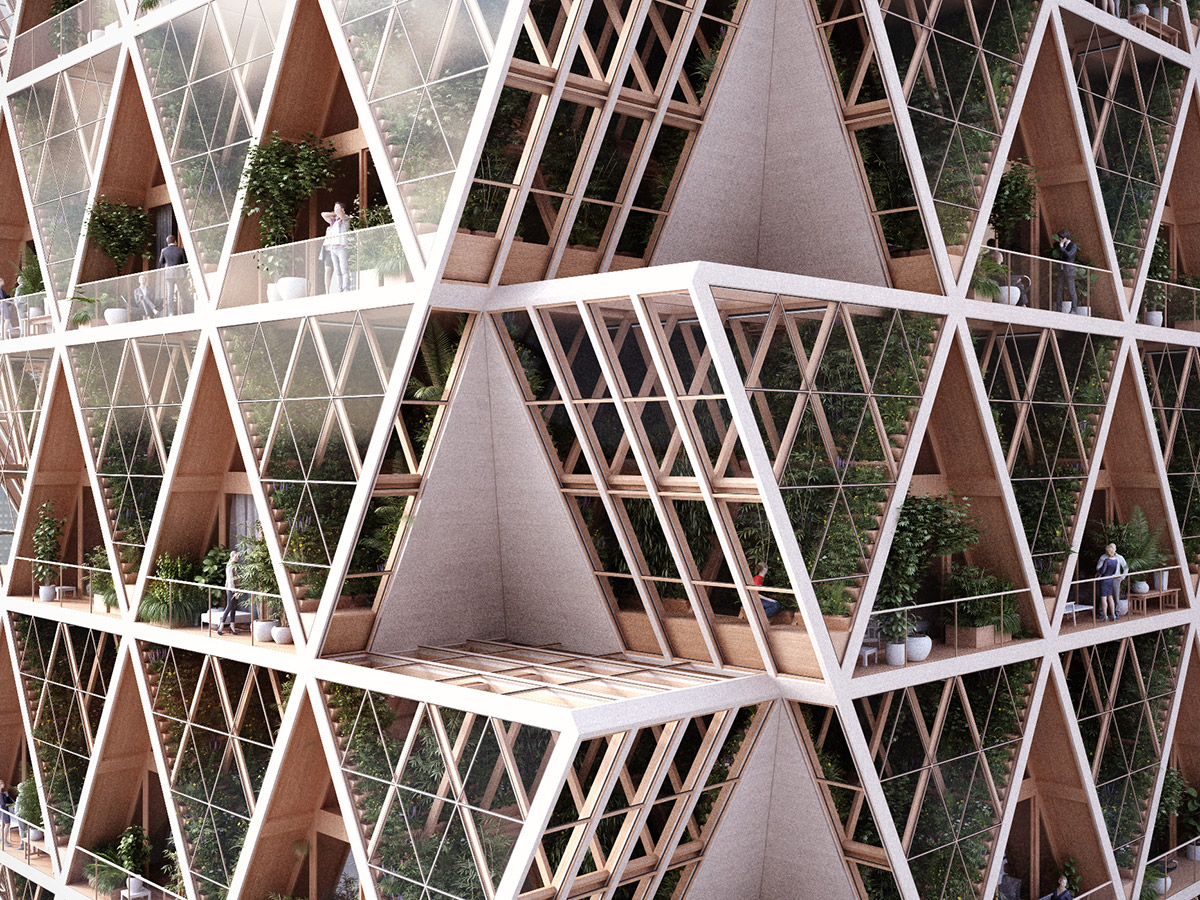

The building system is based on structural clarity of traditional A-Frame houses and connects to a diagrid that runs the loads through the building. Each wall of the frame exists of 3 layers. An inside layer with finishes, electricity and pipes, a middle layer with structure and insulation and an outside layer with gardening elements and water supply. For single-family structures, this systems gives a tool to home-owners to design their own place, based on the needs and the demands to living and farming. Structural and gardening elements, waste management units, water treatment, hydroponics and solar systems can be selected from a catalog of modules and offers a certain flexibility for various layouts.

The hands-on approach of the DIY movement played a big role in the design. Not only for the gardening part of the building, but also for its construction. This method allows owners to self- construct their tiny houses based on their chosen layout. Architecture that is home-built with food that is home-grown. Taller structures are assembled as duplex-sized A-frames, which provide a large open space on the first floor for a living-room and kitchen and a tent-like space on the second floor for bedrooms and bathrooms. The angled walls give space for gardening on their outside and create a V-shaped buffer zone between the apartments. This also lets natural ventilation and natural light into the building. The building invokes a direct connection with a natural surrounding, that stands apart from the concrete landscape of our cities. A tent that is surrounded by nature. A Yin&Yang of colourful gardens and healthy interiors.

The gardens can be used privately for residents to grow their own food, or as a collaborative effort to plant vegetables and herbs for a wider community. After the harvest, the food can be shared or sold at an indoor farmers market on the lower floors of the building. Educational classes, a root cellar and compost units round up the idea of an ecological loop within one building.

Creator: Studio Precht

Name: The Farmhouse

Type: Resedential, Farming

Location: –

Year: 2017 – ongoing

Project partners: Chris Precht, Fei Tang Precht

Credits: Renderings and GIFs by Precht / Animations by Virgin Lemon