23/014

salazar

sequero

medina

Architecture Studio

Peru / Spain / USA

«We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found.»

«We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found.»

«We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found.»

«We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found.»

«We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

We are Laura Salazar, Pablo Sequero and Juan Medina. Together, we founded salazarsequeromedina in 2020, a young collaborative practice with ongoing projects in Peru, Spain, and the US. Our work has been recognized with awards in design and building competitions, and exhibited internationally. We’ve held teaching appointments at Cornell AAP, Syracuse University, Tulane University, Montana State University and the ETSA Madrid. We are dedicated to the practice of building, thinking and teaching.

Portrait – salazarsequeromedina

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

Imagine every single thing in your life as a vector in a cloud diagram pointing toward a center. As students, that center was architecture. It felt inevitable that we should end up here. Architecture gives us so much pleasure.

It was a completely different world when we started studying architecture 15 years ago. The three of us are teaching and find that the discourse in architecture schools is much more inclusive, interconnected, and diverse today – students have more space to share their opinions and explore their interests.

What are your experiences founding your own office and being self-employed? Why did you decide working as a group? Why did you start your own practice? What difficulties did you face?

Working independently is an incredible delight and yet the greatest professional challenge we’ve encountered. We started working together on competitions and small projects while we were employees at other architecture offices, spending weekends and weeknights on our own projects. The three of us viewed each other as independent collaborators, learning from each other, rather than attempting to form an entity.

At the beginning, we did not have the infrastructure and network of contacts that other more established firms have. This lack of capital or a rolodex of clients, everyone should know, makes a big difference. We try to make our way on the longer path of small successes emerging amongst a multiplicity of lost competitions, discarded proposals and limited budgets. Actually, scarcity is something we have learned to thrive on. It has determined a way of thinking about materiality, tectonics, the use of buildings and their lifespan.

Scarcity has clarified our position within the field, and it is borne out of a personal reality. We found that those of our generation who share this path, we have become more inventive, supportive and collegial. And while we keep going, academia is a wonderful bridge that sustains us and which is incredibly rewarding in its own way.

What does “practice” mean to you?

The term practice is quite appropriate to describe the condition of trying. What we represent as a practice is a way of working, in anticipation of a body of work. “Ongoing,” “in progress,” “forthcoming” are the footnotes of our generation.We feel uncomfortable with the very idea of packaging our work as a completed, well-rounded project when the truth is we all maneuver within economies of the unfinished but dressed up.

Our work is cyclical and operates in loops because there is no final product in sight. We cannibalize fragments of our models, especially from those rejected and discarded, into new speculations and proposals. A floor plan from one lost competition is recycled into one we win. The building materials used for our small projects are off-cuts collected from the larger jobs our contractor pursues. Most things will eventually be disassembled and adapted. We’re not complaining. Scarcity is what drives us forward.

We work with the opportunities directly around us. Our clients are middle class and we compete for social projects funded by public institutions. The language of our work relies on the production of generosity over luxury. Air is cheap so we exploit light, atmosphere and thresholds. We’re interested in what can be reclaimed, and what can be found at the hardware store. We collaborate with our peers to share resources. Most of it doesn’t get built, but we keep practicing.

How do you remember your time as an architectural employee/worker?

We are indebted to the experiences we had early on in our careers. Like a lot of young practitioners, we learned discipline, team dynamics and about the type of work that we would like to pursue while working for another practice. It is in many ways an extension of school.

What are your thoughts on the topic of working conditions in the field of architecture?

Working conditions for architects across the board pale in comparison to other industries. Salaries and honoraria for projects are low. Hours are long. Boundaries are blurred. This needs to be spoken about more. It is difficult to make a living as an architect despite the incredible amount of things that we are liable for. We are expected to take on all the roles proficiently: from a skilled draftsperson to a creative fundraiser. There should be stronger unions which defend our interests and greater transparency within our professional community. We need to value each other if we expect society to value our work too.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as a location for practicing architecture? What meaning does location have to you overall?

Currently, we are living in the US and Spain. We have work in Peru, Spain, the US and South Korea. All of them small scale projects, but on four different continents. We are completely delocalised and also try to profit from this situation, working in different time frames and applying learnings from one project into the next one. Almost as if we were operating locally, at a global scale. It is difficult for us to understand and at the same time inherent to our generation.

What does your desk/working space/office look like at the moment?

Zoom and Whatsapp are our studio. In the last year and a half, our team has only met in person five times, two of them purely for fun. We normally meet on Zoom, two or three times per week. Our meetings are fun and productive, we set tasks and goals and catch up two days later. Online meeting has also allowed us to have a much more extensive network of collaborators, which is core to our practice.

Name your favorite …

Book/Magazine: We can mention books that we have had in our hands recently: Tabula Plena by Byrony Roberts, Architecture without Architects by Bernard Rudofsky, The Transparency Society by Byung Chul-Han.

Building: Palais de Tokyo by Lacaton & Vassal. Upper Lawn by Alison and Peter Smithson.

Architect: we’ve learnt the most from our colleagues and collaborators. Again, it would be difficult to pick one architect that we respect the most.

Building material: We are more interested in learning to work with what we can find (locally sourced offcuts and repurposed materials) than becoming experts in any one material in particular.

Spatial Memory: Outdoor rooms that invite interaction: from a patio to a plaza, from a garden to a swimming pool. Also, climbing a tree.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

We hope the notion of tabula rasa disappears from architectural discourse and becomes replaced with the discipline of working with what is found. We need to think of time as a parameter of value which regulates how things are assembled and disassembled. Design should anticipate the transmutability of use and users. We would like to see more open interiors and more inclusive public spaces.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now regarding a more sustainable future for everyone?

The construction industry needs to build less, build only what is enough and use what is there. Speculative real estate is toxic for environmental resilience. It would be great if we could take sustainability more seriously and not just as a trigger word. Rather than relying on alternate means of consumption only, we should think more broadly about minimizing material consumption and design in a way which is adaptive so that any new structures can be translated into future uses.

It is essential to improve the environmental performance of buildings and to reduce the emissions of their construction and operation, but a “platinum” green-certified high rise tower will never be sustainable. Architects have an important role in communicating that these commonly accepted ideas associated with sustainability are misleading.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be?

Become obsessed with things and dive deep but don’t become dogmatic. Also, more sense of humor, less ego.

At the same time, keep it simple.

Do you think social media is changing the field of architecture?

Absolutely. Social media is a great tool to share our work and learn from the work of our colleagues. It is also a great counterpoint to some publications that promote primarily the work of well known established firms. In this sense, we think social media has a positive impact in the field.

On the other hand, social media promotes an image based culture, where immediacy and instagramability of things create an unbalanced environment that it is sometimes tough to keep up with. It can be tricky as it is volatile and ever changing. We will see what happens 5 years down the line.

How do you understand the relation of theory/reflection, practice and teaching in architecture?

It is more urgent than ever to reconcile architectural thinking with building. we run a seminar and lecture series during the spring 2023 semester called Young Prototypes to address the reciprocity between theory and production through the voice of emerging practitioners.

The seminar has become a platform which interrogates the role of design research and criticality in a contemporary practice invested in building. It is a generational x-ray of the methodologies of emerging architects formulating discourse and research around built work.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

The practices which we were lucky enough to have as guests in our seminar, Young Prototypes (watch all lectures online), are inspiring and empowering. Their work foregrounds new narratives and ways of making and thinking about the possibilities for architecture.

They are: Operadora, Soft-Firm, Alfredo Thiermann, Kyle Miller and Molly Hunker, Ofmake, Stefan Sauter, Giona Bierens de Haan, Common Accounts, Ayesha Ghosh, Schneider Luescher, Talleresque, KAL A, Studio Becker Xu, Twenty Three Calvin, Ana Nuno de Buen, AFLPMW, La Cuarta Piel, Associates and.

Project 1

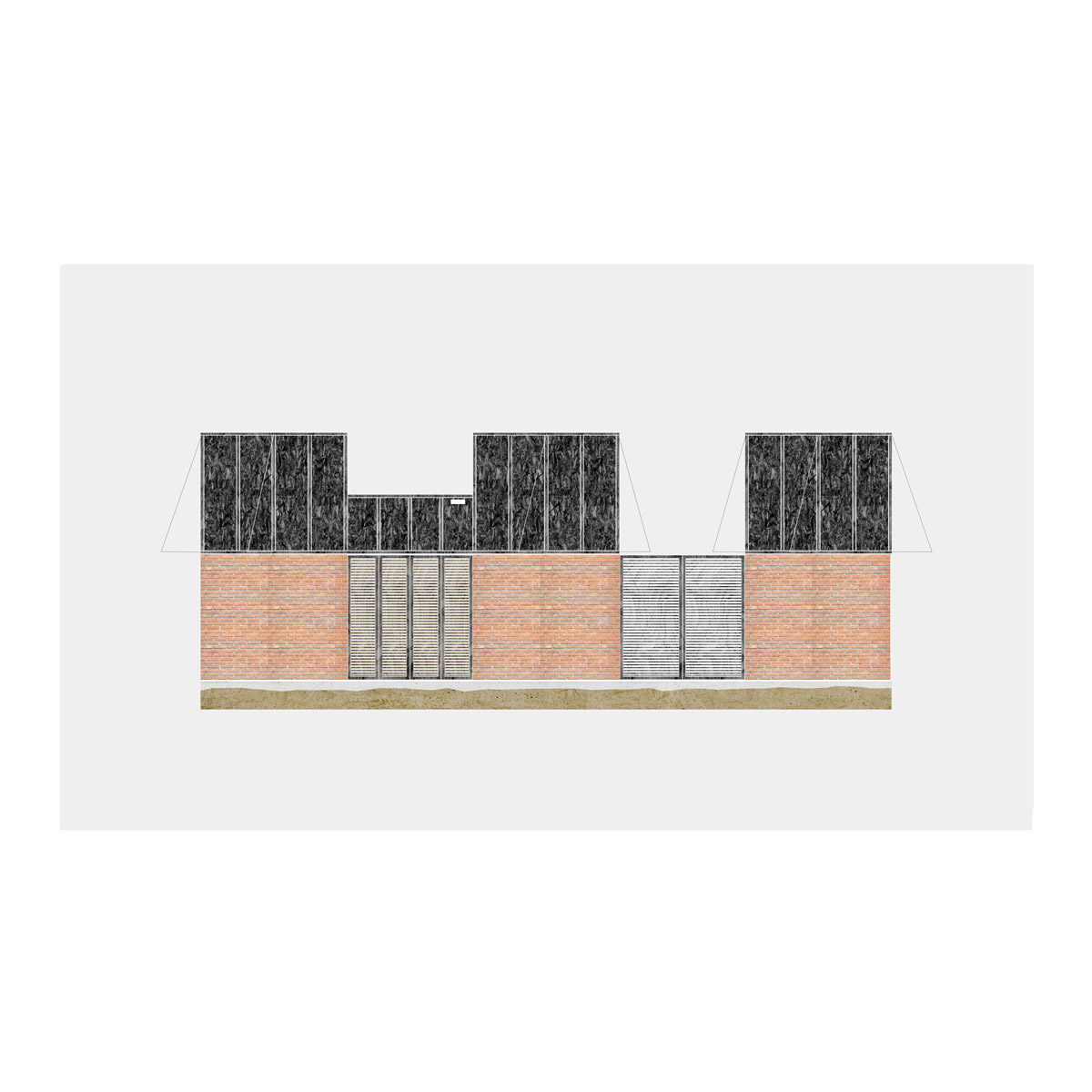

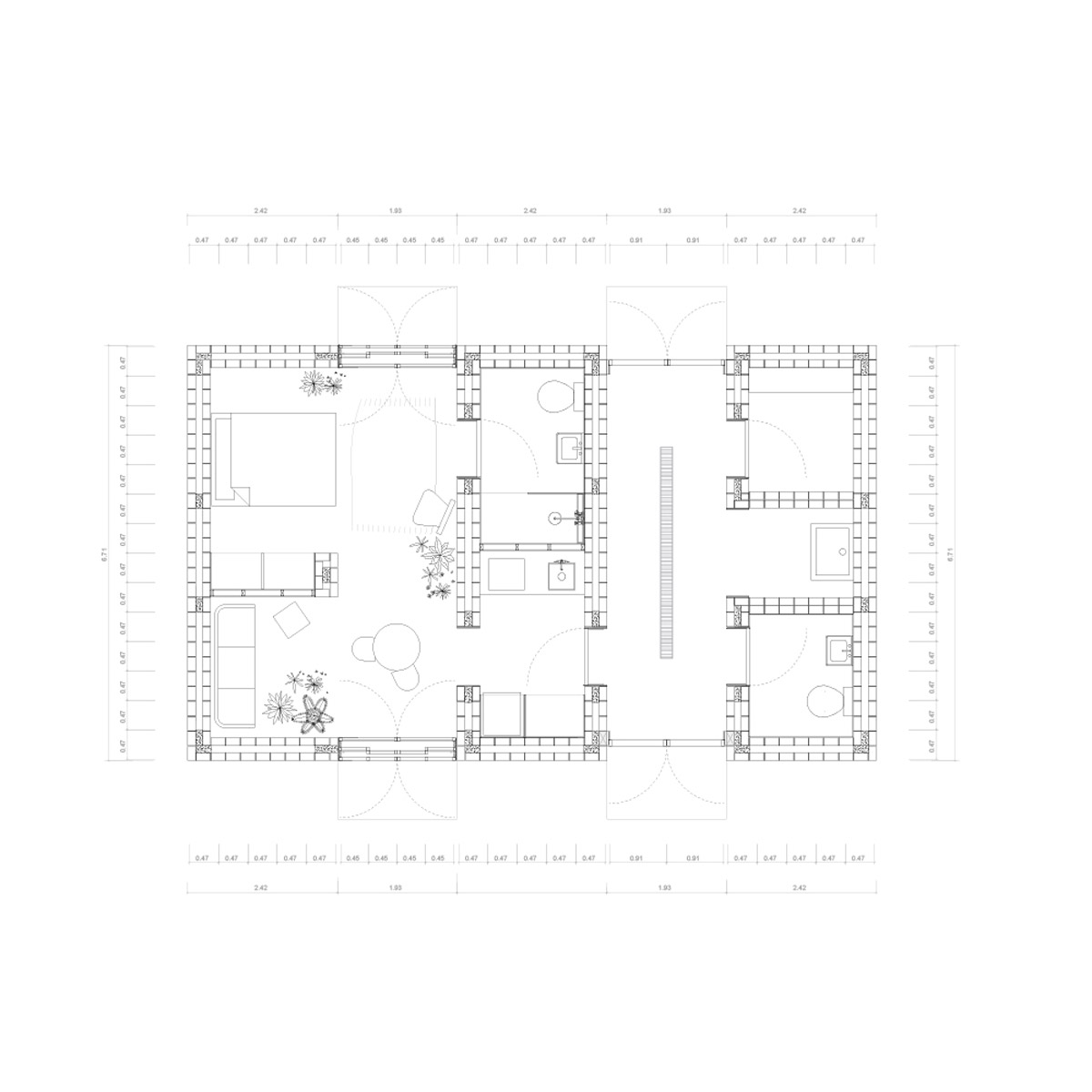

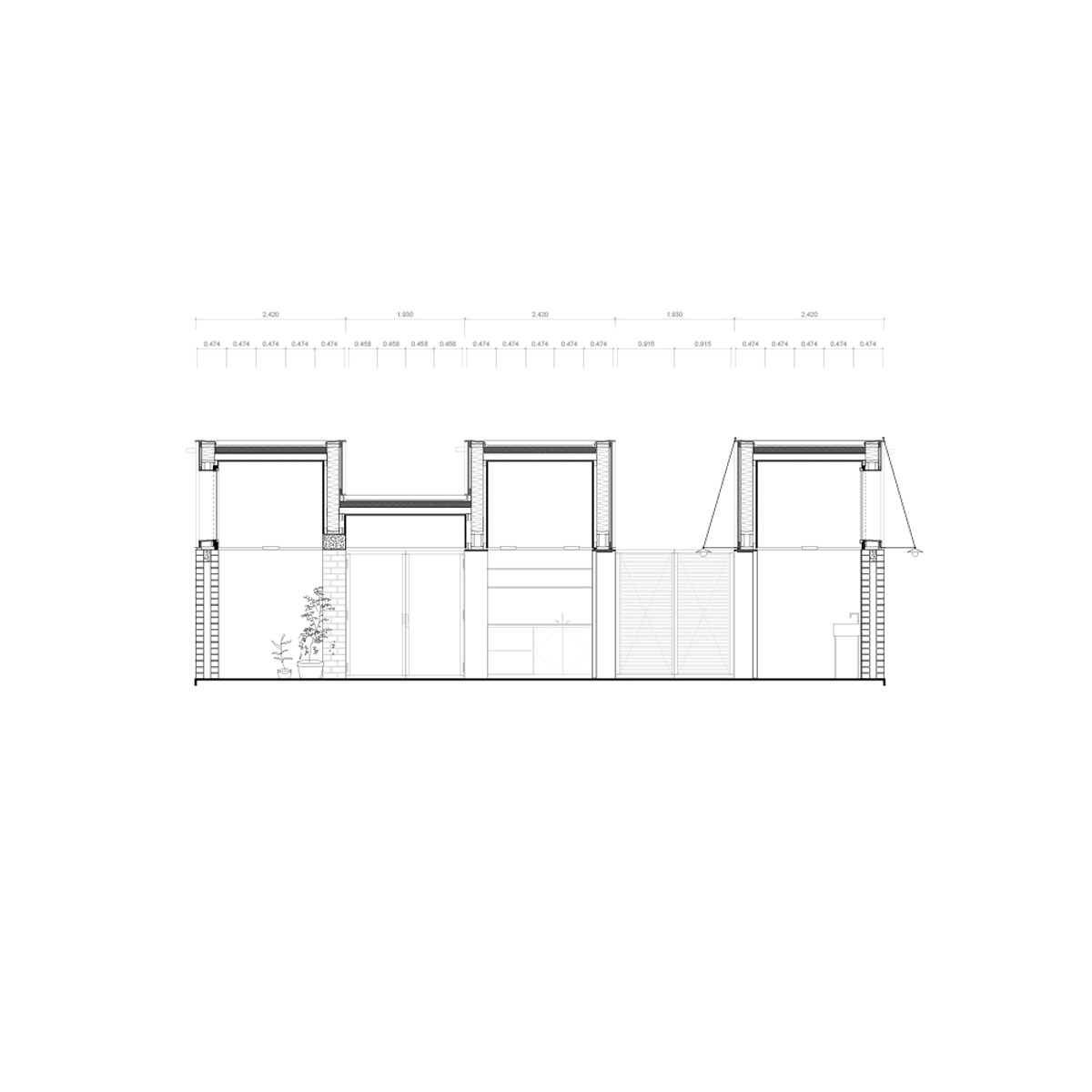

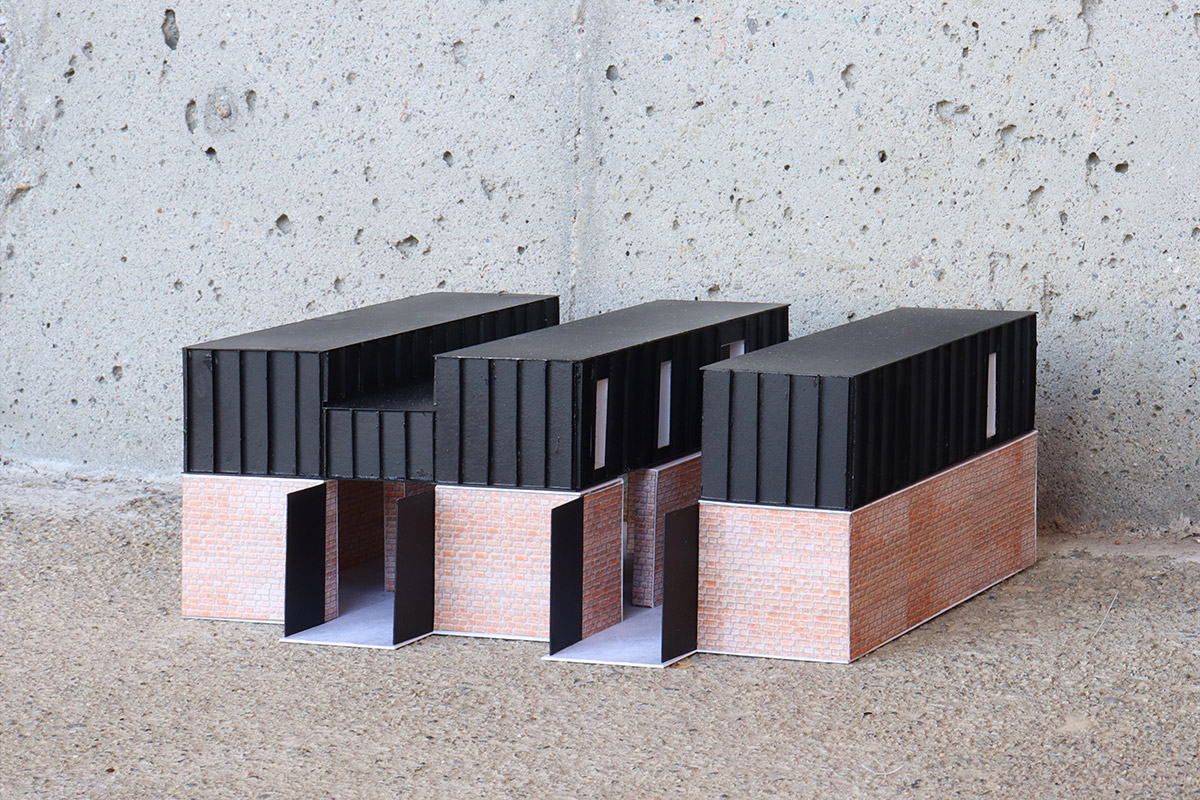

Casa B

El Carmen, Peru

2022-ongoing

Casa B is the secondary house which was built first. It operates as a kind of repository for all the subsidiary activities of the main house which is yet to come. It is a guest house, a space for storage, laundry, and a piece of support infrastructure for an orchard. It is the introverted twin to a greenhouse.

The brick socle rises to 2 meters, comprising a datum line for functional elements: doors, shelving, furniture and fixtures. It is constructed of “ladrillo recocho,” meaning overcooked, which is a repurposed clinker brick, salvaged over months from discarded stock at local brick kilns. Over it, sits a simple wood-framed structure as a sequence of forms abstracting the skylight typology of regional construction into three programmatic bands. It is a project that becomes generous in section as its minimal footprint gives way to a bright and soaring interior. In between each rising volume, wide doors melt the interstice with the exterior.

Project 2

Greenhouse for Plants and Humans

El Carmen, Peru

2023

Two adjacent bodies are perfectly asymmetrical twins: half a greenhouse and half an outdoor living room. Their adjacency encourages a certain symbiosis between two dissimilar functions which is an interior for plants and an exterior for people. The fruit goes to the table; the hands clean the leaves.

The architecture looks toward the roadside vernacular of its surroundings, as a dictionary of shapes and attitudes about temporary structures. The typological character of the add-on emerges as the veranda, awning, forecourt, or overbuild – a bit unsteady but necessary – as strategies of shading, ventilation, daylighting, and modulation.

The base of floors, walls, and chimney are constructed as steady, monolithic objects, which are impermeable to time. A brick socle rises to 2 meters, comprising a datum line for functional elements. This greenhouse for plants and humans is constructed of “ladrillo recocho,” meaning overcooked, which is a repurposed clinker brick, salvaged over months from discarded stock at local brick kilns.

The assembly of the elemental, diaphanous metal structure above suggests a transmutability in its lightness. Its humble scale allows for sourcing from the offcuts of agricultural infrastructure nearby. It is a greenhouse now, but it might be disassembled and take on a different life in the future. Any number of configurations or permutations could take place in which these adjacent spaces take on other functions or merge with each other as one.

The goal of the project is to reduce the carbon footprint of its construction through life-cycle strategies including the salvaging of discarded or overstock materials, which are locally sourced. Plants grown in the greenhouse such as berries, peppers, herbs, tomatoes and other fruits are protected from pests by a mesh covering.

Photography: Ivan Salinero

Website: salazarsequeromedina.com

Instagram: @salazarsequeromedina

Photo Credits: © salazarsequeromedina, © Ivan Salinero (Greenhouse)

Interview: kntxtr, kb, 10/2023