18/032

Stefan Wülser

Architect

Zurich

«How could we bring back the fascination for real physical experiences in a world designed around the desire for comfort and safety?»

«How could we bring back the fascination for real physical experiences in a world designed around the desire for comfort and safety?»

«How could we bring back the fascination for real physical experiences in a world designed around the desire for comfort and safety?»

«How could we bring back the fascination for real physical experiences in a world designed around the desire for comfort and safety?»

Please introduce yourself and your office.

I’m Stefan Wülser an architect born and educated in Switzerland. As a counterpart to my reliable studies at the swiss “University of applied arts and science” I went to London to attend lectures and workshops at the AA after my diploma. I started to deepen my interests for mathematics, music and philosophy at that time and had no career plan or precise idea of how it’s going to take off from there. I very much enjoyed those enriching and contradictory perspectives but I came back to Switzerland for my first job as architect and I live in Zurich ever since. In 2013 I had the possibility to start teaching at ETH (at the guest-professorship of Winy Maas / T?F) which gave me another new point of view but also the freedom to start being self-employed. Together with Nicolaj Bechtel I founded “Wülser Bechtel Architekten”. After about one year of working together we’ve won a large competition for a social housing project (together with a partner office) which will take at least until 2022 to be built but we also realized 5 smaller projects in the meantime. Right now I am about to adapt my daily routine so I can focus more on theoretical work and non-profit studies because I believe it’s important to contribute to an interesting and active discourse.

How would you describe the relation between theory and practice?

It’s this inherent tension between the built environment, it’s reception and it’s actual function on one side and the theoretical and political positions on the other side that keep me motivated. There’s a huge amount of fog and mystification around common practices and there is an even bigger discrepancy between how rational architecture as a business is and how complex, influential and full of possibilities architecture as “Baukultur” could be. There are very professional management decisions and there are artistic and intellectual argumentations – two approaches that are rarely compatible but never strictly separated. In practice there are so many people involved and so many responsibilities distributed that it’s hard to find a common language let alone common goals. The notion of “Baukultur” seems very important to me here and it’s a pity that there’s no translation for it but there’s whole books (the culture of building, 2006 by Howard Davis f.e.) written about what it’s conception could contribute to the understanding of both theory and practice.

Baukultur for me means (before all other aspects) that we have to develop an understanding of “building things” as a contribution to our culture again. Architecture in itself is an interesting in-between-world neither art nor service. It’s in that sense a very holistic and very strong and contemporary form of cultural expression. As Pier Vittorio Aureli said: “There’s no way back from urbanization”. So we need to see and understand the specific condition we live and work in today and I think it’s very important for our generation to focus on the bigger picture and to reflect about the meaning of what we’re actually doing. Architecture theory is one way to do so.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

By coincidence to be honest! As a child I was always fascinated by patterns. I was thinking about going to some kind of mathematic or computer science studies for a long time before I figured out that I might miss the human aspect. I still have a very pattern- or system-based view on architecture and the world and I always strive to understand the mechanics behind a phenomena – but today it’s the social and the political layers of design that are most important to me.

What does your desk/working space look like?

It’s a former bar that was transformed to a shop that was transformed to a gallery that was transformed to our studio. I love working on ground floor in the city center because of the constant connection to urban space and to people. The constant change of light and weather, traffic jams, people doing loud phone calls, strangers asking for directions and even the shady guys outside when working late at night make this space a great environment to work on questions of (public) space.

How would you describe the relation between theory and practice?

It’s this inherent tension between the built environment, it’s reception and it’s actual function on one side and the theoretical and political positions on the other side that keep me motivated. There’s a huge amount of fog and mystification around common practices and there is an even bigger discrepancy between how rational architecture as a business is and how complex, influential and full of possibilities architecture as “Baukultur” could be. There are very professional management decisions and there are artistic and intellectual argumentations – two approaches that are rarely compatible but never strictly separated. In practice there are so many people involved and so many responsibilities distributed that it’s hard to find a common language let alone common goals. The notion of “Baukultur” seems very important to me here and it’s a pity that there’s no translation for it but there’s whole books (the culture of building, 2006 by Howard Davis f.e.) written about what it’s conception could contribute to the understanding of both theory and practice.

Baukultur for me means (before all other aspects) that we have to develop an understanding of “building things” as a contribution to our culture again. Architecture in itself is an interesting in-between-world neither art nor service. It’s in that sense a very holistic and very strong and contemporary form of cultural expression. As Pier Vittorio Aureli said: “There’s no way back from urbanization”. So we need to see and understand the specific condition we live and work in today and I think it’s very important for our generation to focus on the bigger picture and to reflect about the meaning of what we’re actually doing. Architecture theory is one way to do so.

How did you find your way into the field of Architecture?

By coincidence to be honest! As a child I was always fascinated by patterns. I was thinking about going to some kind of mathematic or computer science studies for a long time before I figured out that I might miss the human aspect. I still have a very pattern- or system-based view on architecture and the world and I always strive to understand the mechanics behind a phenomena – but today it’s the social and the political layers of design that are most important to me.

What does your desk/working space look like?

It’s a former bar that was transformed to a shop that was transformed to a gallery that was transformed to our studio. I love working on ground floor in the city center because of the constant connection to urban space and to people. The constant change of light and weather, traffic jams, people doing loud phone calls, strangers asking for directions and even the shady guys outside when working late at night make this space a great environment to work on questions of (public) space.

Studio Seebahnstrasse, Zürich

Studio Seebahnstrasse, Zürich

How would you characterize Zürich as a location for architects? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

It’s not easy to compare the city where I spend most of my time and which I know best to any other place. Zurich is a real love-hate-relationship for me. It’s a great place to live (which I think is very important to make it a great place to work) and for it’s relative smallness it offers a lot in terms of culture and a varied discourse about art and society. There is an insane amount of building projects at the same time and there is money being spent wherever you look. But if you look at what is being built and how money is being spent the enthusiasm quickly disappears. I would dare to claim that there’s no other place with such a mastery in building details and construction quality. In the city where Zwingli was crafting the protestant reformation there is this ascetic tradition of self-controlled and well thought decisions. There’s almost no big aesthetic flaws being made, no super-ugly and no intrusive designs as in other rich european cities - but at the same time it seems that architecture is so busy being neat that it is losing any subversive strenght and it’s potential nonconformist momentum. In general built architecture seem to prefer avoiding mistakes before trying to do anything outstanding. One could almost argue that being boring is a way of being very radical when there is loads of money being spent. But I think it’s far more pragmatic then that: It’s about compromises and caution and about not showing exuberant joy nor immodest desire.

So what influences me in my work is that the city makes me wonder how we could possibly bring back the fascination for real physical experiences, for friction, for strong emotions and for the unexpected in this world designed around the desire for comfort and safety. I really believe in cause and effect here. We will be able to shift paradigms in how cities develop if we can first shift our expectations on what qualities we want from cities. That believe and the fact that there are a lot of other young architects who are debating similar or relative topics makes me quite optimistic about how our profession can contribute in the near future. There is an interesting ongoing discourse about gentrification and densification for example. For the public it is mainly political but it is also starting to affect how architects debate their work. If we go on doing so – and if we start to relate our argumentation to actual problems of all the diverse people who live in the built environment – we might actually be relevant.

What are your experiences working as a self-employed architect?

I’m very thankful about the situation I’m in. As explained in the beginning I kind of had a quick start with winning a rather large competition. That was very nice but also very challenging since we had to come up with office structures and hire a couple of employees right away. The good thing about the direction everything is going right now is that I can really work in different fields. The housing projects quickly made me understand processes and specific routines inherent to project development. At the same time the smaller projects gave a lot of freedom to explore certain strategies how to translate my ideas and positions in design meant to be built within economic boundaries. As stated earlier I really think theory is important. At the same time I think it’s crucial to use the very own instrument of our profession to communicate: architectural projects. We need to reflect the world we live in but we also need to have visions and dare to propose alternatives! From the very beginning of being self employed I tried to build a network that enables me to get direct commissions and not mainly rely on competitions. Those commissions are small scale projects but they help in two ways. First they allow me the freedom to question program and to actually design the program. Second they allow me the economic freedom to develop idealistic competition entries without compromises. Being self-employed means constant stress and a constant insecurity in my personal experience but it was the best decision I can think of. As Rem Koolhaas once said “it allows you to be irresponsible and invest in your work”.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

A spatial contribution to culture.

What and who are your masters of architecture?

Books…

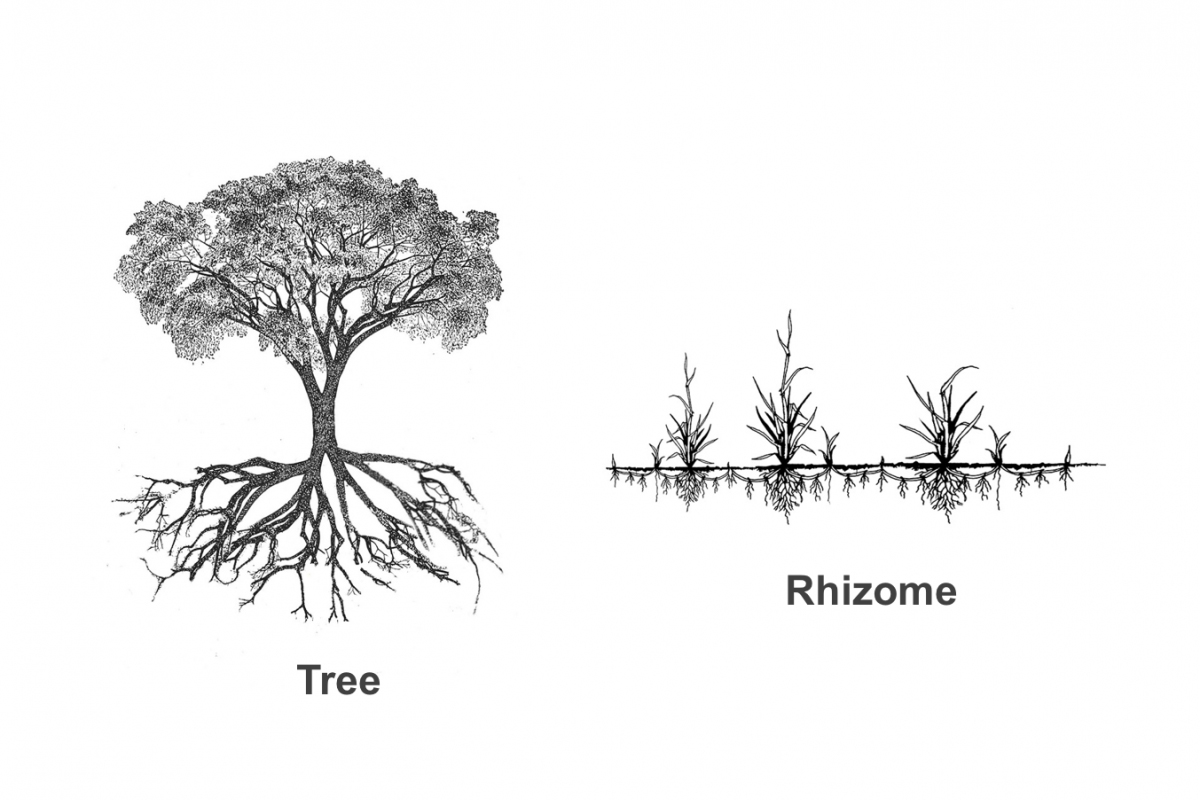

Deleuze and Guattari’s “Rhizom”. A real eye opener about the limitations inherent in the logical structures of our thinking and a huge motivation to question hierarchies and how much of an illusion freedom is as long as there’s hierarchies – in any kind of system, or structure.

Sigmund Freud’s Das “Unbehagen in der Kultur”. The way Freud writes about our ability to experience real pleasure or real emotions is very relevant to my idea of perception of space. How can we expect people to value architecture when we are unable to create spatial situations that affect people beyond simple aesthetic pleasure or comfort.

Robert Venturi’s “Complexity and Contradiction” to also include a classic architecture book. Venturi’s criticism of oversimplification and schematic architectural projects is more relevant then ever today. We live in a world with to many images and not enough strong realities.

Buildings…

Peter Märkli’s early houses. A fascinating body of work! The single family homes in Trübbach but even more the rather brutal house in Sargans. It creates a certain kind of friction between house and public space that is quite unusual in todays architecture.

Aldo Rossi’s San Cataldo sanctuary. A design flawless beyond explanation. It works strictly with Rossi’s limited vocabulary of architectural elements typical for his 70s projects. It’s built melancholia – a physical experience that is so strong it can change how you feel every time you visit it.

Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa Del Fascio. A mathematical antipode to Rossi’s metaphysics! Geometry as representation of idealogy – built political program but with a strange sensibility that is hard to believe. The way Terragni uses light and reflections within his manifold geometrical design is unique.

Buildings…

Peter Märkli’s early houses. A fascinating body of work! The single family homes in Trübbach but even more the rather brutal house in Sargans. It creates a certain kind of friction between house and public space that is quite unusual in todays architecture.

Aldo Rossi’s San Cataldo sanctuary. A design flawless beyond explanation. It works strictly with Rossi’s limited vocabulary of architectural elements typical for his 70s projects. It’s built melancholia – a physical experience that is so strong it can change how you feel every time you visit it.

Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa Del Fascio. A mathematical antipode to Rossi’s metaphysics! Geometry as representation of idealogy – built political program but with a strange sensibility that is hard to believe. The way Terragni uses light and reflections within his manifold geometrical design is unique.

Person…

Frank Zappa for the way he always understood his artistic work in the context of society and politics – for his fearless and almost heroic perspective on his very own generation.

Roman Signer for the joy he expresses and creates with art.

And if I have to name an architect and only one – there is no way around Rem Koolhaas. All the others that come to my mind are either early allies of Koolhaas or part of a later generation that based their thoughts on his work.

Roman Signer – House with rockets, Gonten, 1981

Roman Signer – House with rockets, Gonten, 1981

What has to change in the Architecture Industry?

That’s kind of an invitation: The first thing is to get rid of this very limiting idea of architecture as an industry! There is the building industry which is part of architecture but it’s not an equivalent to architecture. Architecture is a service and it’s also part of our cultural identity. Both the design and the realization process are based on those two. We have ‘building industry’ (service) and ‘Baukunst’ (culture) that together form the realization part and we have ‘typologies’ (service) and ‘inherent values or identity’ (culture) that make a design. All four are equally important to make a successful project but I’d say it’s the notion of ‘values’ that should become the focus of our current discussion. Architecture has a big responsibility to be critical. Cities are built environments – dynamic systems that act as mirrors of social values. It not only confronts us but also shapes our values as a constant reciprocal influence. If we as designers focus mainly on aesthetics and comfort we will contribute in creating a rather shallow world. When I said we need to develop visions and alternatives I actually meant alternatives that go beyond architectural form. How do we want to live? What kind of society do we want to be? And what kind of spatial reality do we need to become this society?

Stefan Wülser – What If?, reflection about Globus Provisorium Zürich, 2018

Stefan Wülser – What If?, reflection about Globus Provisorium Zürich, 2018

Project

Umbau

Wohnhaus Windisch

2017

In one of the small transformations I mentioned, we (it’s one of the works with Nicolaj Bechtel) were asked to transform a house built in the 30s with two small flats to a home for one young family with two kids. There was very little money and the humble idea to only change what’s necessary. The conversation with the clients made us realize that the floor plan layout their ideal home would have is completely different from what we have to deal with here. The house was quite generic but had a lot of charm and it was made of humble but long lasting materials. Neither contrasting the normality of this house nor to blur our transformations with it seemed promising approaches to for a strong result that might add to their daily life beyond the point of fulfilling functions.

Instead of designing small but effective interventions to connect the two flats we started to overlay what we think might be their ideal home with the existing plans. We didn’t want to accept the limitations of the transformations extense but instead tried to find strategies to limit the actual amount of work/ money per square meter. Despite being asked to not change a lot we only respected the outer walls and started to appreciate the discrepancy of ideal and reality in the inside. We adjusted privacy and openness by subtracting from what was there. We only added very little elements and never used heavy or mineralic materials for the new. Existing elements where cut in halves where necessary and the scars of this subtractive approach became very welcome additions to the character of the house. The old, the new and the traces of our transformation coexist and are valued equally. To emphasize on the different rough textures we gave the house a proper whitewash. It gives the house a peculiar but poetic grace full of varied surfaces and hard-to-decode little sidestories. There is windows enlarged, windows completely closed, walls taken away completely and wooden paneling cutted. The spaces are constantely challenging our habits and reflexes for equalization with it’s consequent rejection of make up. It’s raw and it’s radical but it creates a lot of real qualities when used.

Project

Umbau

Wohnhaus Windisch

2017

In one of the small transformations I mentioned, we (it’s one of the works with Nicolaj Bechtel) were asked to transform a house built in the 30s with two small flats to a home for one young family with two kids. There was very little money and the humble idea to only change what’s necessary. The conversation with the clients made us realize that the floor plan layout their ideal home would have is completely different from what we have to deal with here. The house was quite generic but had a lot of charm and it was made of humble but long lasting materials. Neither contrasting the normality of this house nor to blur our transformations with it seemed promising approaches to for a strong result that might add to their daily life beyond the point of fulfilling functions.

Instead of designing small but effective interventions to connect the two flats we started to overlay what we think might be their ideal home with the existing plans. We didn’t want to accept the limitations of the transformations extense but instead tried to find strategies to limit the actual amount of work/ money per square meter. Despite being asked to not change a lot we only respected the outer walls and started to appreciate the discrepancy of ideal and reality in the inside. We adjusted privacy and openness by subtracting from what was there. We only added very little elements and never used heavy or mineralic materials for the new. Existing elements where cut in halves where necessary and the scars of this subtractive approach became very welcome additions to the character of the house. The old, the new and the traces of our transformation coexist and are valued equally. To emphasize on the different rough textures we gave the house a proper whitewash. It gives the house a peculiar but poetic grace full of varied surfaces and hard-to-decode little sidestories. There is windows enlarged, windows completely closed, walls taken away completely and wooden paneling cutted. The spaces are constantely challenging our habits and reflexes for equalization with it’s consequent rejection of make up. It’s raw and it’s radical but it creates a lot of real qualities when used.

Wülser Bechtel Architekten – Umbau EFH Windisch, Fotos: Nicolaj Bechtel, 2017

Wülser Bechtel Architekten – Umbau EFH Windisch, Fotos: Nicolaj Bechtel, 2017