21/028

Theresa Reisenhofer

super tomorrow architecture

Styria

«There is so much to do on the countryside, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.»

«There is so much to do on the countryside, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.»

«There is so much to do on the countryside, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.»

«There is so much to do on the countryside, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.»

«There is so much to do on the countryside, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

My name is Theresa Reisenhofer and I work independently as an architect mostly from our small farm in the east of Styria in Austria. I work alone and in cooperation with other architects and architecture offices in various project sizes and project typeswhose I know mostly from my studies at the Graz University of Technology. Additionally, my boyfriend and I run a small farm (about 3 ha) with sheeps, soon our own chickens and a self-supply garden for us and – in case there is anything left – also for others. Further friends and I have a stoner rock band, there I play electric guitar. We jam a lot and did some gigs before Corona started. This and the work in the nature are the perfect compensation to working in architecture in front of the computer for mostly the whole time.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

I grew up in Styria (Austria) in the countryside on a farm with four generations living together and four siblings. My parents ran an organic farm with its own cheese dairy and direct marketing as pioneers in the 90s. In this environment, there are no touching points with architecture as you might imagine. It was not really architecturally appealing at home either. Neither inside, nor outside; it was just a normal farm. I had a beautiful childhood though as our parents raised us very as open human beings and in close connection with nature. Not in a hippie way, but more down to earth.

I’ve always been good at drawing and I got interested in computer programs very early. I tried my first 3D program – like Paint, only three-dimensional – when I was 10 years, it was in the 90s, and from then on, I realized my fascination for designing space in combination with the tools I was able to use on the computer. After high school, which focused on art, design and interior design in Graz, I didn’t really want to become an architect. Most of the architects I knew – only men at that time – I found very conceited and condescending and I definitely didn’t want to become like that.

But after an internship at Coop Himmelb(l)au in Vienna, my opinion changed. There I met many interesting – as well female – architects and was able to understand the extensive possibilities of architecture for the first time. Designing and creating concepts, vision and ideas, planning and the process and showing how it could be and what possibilities there are for so many topics. That still fascinates me today and drives me and my work. However, I don’t necessarily agree with the attitude and language of Coop Himmelblau anymore. I’m more of a gabled houses fan now.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your time at university?

First of all, I think about all the time I was not present at the school, as I worked in architectural offices throughout my studies to earn my living, just like many other students at TU Graz as well. The experience gained through the work was an enormous advantage for me in terms of practice. Anyways, I often had to decide whether to attend this lecture or to go to work. I have to admit that from the end of my bachelor’s degree I was no longer present in any lectures. I don’t want to glorify that, but I was really conflicted and then preferred working in the office, but I still regret that to this day because you can’t make up for the time lost.

Since I worked a lot and knew the “real life” in architecture offices, so to speak, I deliberately chose design tasks in my Master’s that were very much in the theoretical realm, as was my Master’s thesis, which was a purely scientific study. I used my studies for focusing on what I couldn’t necessarily focus on later in an office.

Due to working the entire time during my studies in an office I also realized the extreme difference between university and the world outside. Everything that happens at the university takes place in a protected bubble without other people not used to the world of architecture. There is no contact to users, clients, politicians or just normal people. It feels like an untouchable ivory tower. Most students are taught by architects, present to architects and get feedback and ultimately an assessment from architects. All events as well as discourse related to architecture are made by and for architects – a robust bubble. When architecture students graduate, they are often shocked by lack of understanding in the general public. This is a big problem as the architectural work is hardly valued on a more general public level.

What are your experiences founding your own studio and working as self-employed architect?

I like to work as an architect very much, but I am also interested in so many other things, the farm, music, family. It was obvious for me that I’d work independently as an architect one day. Architecture as a profession is perfect for this, as you can work flexibly from anywhere and also in any terms of time.

So I just decided to go for it at a time. To set up an architecture office, you need to do an extra exam after your studies in Austria. One needs three years practical time, one year at the construction sites. Unfortunately, even after 10 years of professional experience, I did not have enough practical experience as I lacked time on construction sites. I was always put into design and competition phases of projects which was a big disadvantage.

But as I was pregnant, I didn’t want to start all over again in another practice. I decided to find my own way to get licensed and founded a technical office for interior design in May 2021. Thanks to the very good economic situation in the construction industry at the moment, I received orders from the very beginning and have been able to make ends meet really well. I also do competitions in cooperation with various offices and prepare for our soon-to-be small family, which should then be complete in November.

How would you characterize the city you are currently based at as location for practicing architecture? How is the context (of this specific place) influencing your work?

In spring we rented a small farm with 3 hectares of pasture and forest in Hinterwald, Feistritztal in eastern Styria. I am not sure how many inhabitants the village has, there are around 10 houses. Our house is situated a little bit outside surrounded by forest with one neighbor only. I usually go to Graz once or twice a week for meetings.

I have spent about half of my life on the countryside and the other half in cities (Graz and Vienna). Therefore, I know both sides very well, but we have deliberately chosen the countryside because it is cheaper and we can simply do more. We have more freedom and space; we can just build something when we feel like it. It’s somehow more possible without consuming anything or spending money directly. If the infrastructure would be developed better (public transport, internet, etc.) the countryside could be really attractive for families with jobs in the service sector: They could simply work independently in home office.

From an architect’s point of view, I see many aspects to be addressed on the countryside. The profession itself is seen as something that doesn’t belong to the countryside. Architecture is perceived as something that comes from outside, from the city. As if architecture weren’t for ordinary buildings or for ordinary people. For me personally, it is not so easy take off my architectural glasses. There are unfortunately many things in the countryside that make me angry, sad or faint. How, where and what is built for example. Grown village structures and identities are destroyed. Landscapes are disfigured.

There are so many villages with only one function: housing. There is no market, no bank, no trade, no craft, often no church anymore. People only live there and commute alone in a car to work. Villages are extinct during the day. Current urban planning already learned from the mistakes of separating functionalities of modern planning. But on the countryside, there is no change in sight, although there are role models, for example, the Bregenzer Wald in Vorarlberg. There one can experience the qualities of a life in the village, with a good mix of crafts and agriculture, tourism, etc. and perfect public transport.

In addition, people are committed to their own region and are willing to support it. People shop locally, hire local craftsmen, eat in the village restaurant. The money stays in the region, which is one of the most important factors for regions to flourish. There is so much to do, but architects are not positioned to tackle these problems or are simply ignoring them.

Roland Gnaiger, a very well-known architect in Austria and former professor at the Faculty of Architecture at the University of the Arts in Linz, who is very committed to the countryside, co-founded the association Landluft and has described this feeling and situation in his essay Die Region ist ein Fluss very aptly:

„Die Beziehung zwischen der Architektur und dem Land ist die Geschichte einer verletzten und zurückgewiesenen Liebe! Das Land verweigert sich der Architektur, die Architektur verweigert sich dem Land. Und um weiter im Jargon der Psychologie zu bleiben: Das Land verweigert Geistigkeit und die Architektur die Bodenhaftung. Etwas alchimistisch formuliert könnte man sagen, Land und Luft sind auseinander geraten.

Etwas konkreter ausgedrückt verlief diese Beziehungsgeschichte folgendermaßen: Architekten/Architektinnen und andere Personen mit einer etwas verfeinerten optischen und ästhetischen Wahrnehmung haben nach Jahren der Abwesenheit die Orte ihrer Kindheit und/oder Jugend „nicht mehr erkannt“.

Jene Orte also in denen sie genau diese Wahrnehmung entwickelt haben, haben sich mehr oder weniger radikal in wesentlichen, meist substanziellen Teilen verändert. Diese Veränderung war fast immer eine Zerstörung oder zumindest ein Verlust an Geistigkeit, eine Auflösung von Raum, Struktur und Form. Die Folge davon war bei den Sensiblen ein subtiles Leiden. Die Reaktion auf diese „Kränkung“ ist Rückzug.“

“The relationship between architecture and the countryside is the story of a hurt and rejected love! The land refuses architecture, architecture refuses the land. And to continue in the jargon of psychology: The land refuses intellectuality and architecture refuses groundedness. Somewhat alchemistically formulated, one could say that land and air have come apart.

To put it a bit more specific, the story of this relationship went as follows: Architects and other persons with a somewhat refined optical and aesthetic perception have, after years of absence, “no longer recognized” the places of their childhood and/or youth.

Those places in which they have developed exactly this perception, have changed more or less radically in their essential, mostly substantial parts. This change was almost always a destruction or at least a loss of spirituality, a dissolution of space, structure and form. The consequence of this, in the sensitive, was a subtle suffering. The reaction to this “mortification” is withdrawal.”

This topic is a very special one to me as it was as well the topic I dealt with in my Master’s Thesis under the title „ArchitektInnen und das Land – eine Kapitulation?“ (Architects and the countryside – a surrender?). I approached the relationship between architects and the countryside in the form of a scientific study, to develop a more profound understanding of the dynamics. Living in the city, I have always felt like a country bumpkin. I think growing up at and living in the countryside shapes you a lot. To this day, this is a part of me and I also want the countryside to become part of my work as an architect, no matter how difficult it is. This is my motivation and drives every new project and task I take on. No matter how insoluble it might seem, you just have to find the right way to solve it.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Working Spaces – Green House and Desk, in Styria, Austria

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

I love architecture, but it is my job not my life. In my life there is more than architecture.

Name your favorite …

Material: I love “honest” material: Wood that you can experience as wood, steel and brick that are visible and not only fake but shown as functional parts of a building. No fake, no plastic, no decor. I also love materials that are already there to be easily recycled. What does your desk/working space look like

Building & Spatial Memory: Our old „Vierkanthof,“ from around 1851 with brick porch and a round arch. This is my favorite building and also my greatest spatial memory. To plan through it was quasi my first design for myself, which I imagined in my mind. Unfortunately, it no longer exists. It was torn down a few years ago.

How do you communicate/present Architecture?

I communicate architecture mainly through social media platforms, like Facebook and Instagram. Although I hate being dependent on data there, it offers great advantages for architecture mediation and the platforms are helpful to set up a business. I don’t see the future in a classic homepage anymore, which is too rigid and not interactive enough.

Further I talk a lot about architecture with everyone I meet. For very many people who have nothing to do with architecture, THE ARCHITECT is really something elitist, especially in the countryside. People are disappointed oftentimes when they see me as an architect, and I do not meet their expectations. Haha. But this is also my goal: I want to counteract these persistent clichés. I am neither the typical architect, nor the typical farmer, nor the typical woman and this is amazing!

I want to make people realize that architecture affects them too. That architecture is a profession like any other, neither better nor worse, and that like other professions architects have skills that are important and should be used. I wouldn’t install my own electrical cables, but would rather get professional help to do it for me, and that’s how it should be done with the design of space and landscape.

My Boyfriend grew up in Vorarlberg. There the work of architects and the approach to architecture in general is very different. There it is quite normal for anyone to call in an architect to plan his*her house. The expertise of architects is recognized and utilized. That is missing here in Styria and almost all over Austria. But the positive aspect is, that there are examples like Vorarlberg. So we know that it can be done differently and we can learn from it.

What essential actions do we need to take as architects now to be able to design a better future for everyone? From your perspective: What are the (political, legislative, etc.) influencing factors that matter (restrict/enable actors) most?

In my opinion one of the worst things architects can do is being unpolitical. I think every action is somehow political, no matter what kind, what branch, or what profession one is working in. Actions that touch the interests of the general public are always political! Therefore, any architecture – whether it is a simple family house, a public building, a commercial building, each part of our built environment – is political! All architects should really start to reflect on this. Political awareness should be part of architectural studies as during the time at the university there is still space to explore and express political messages. In professional life and in the private sector, it becomes more and more difficult to do so.

Another aspect is the general understanding of architecture. In my opinion, Hans Hollein drew the wrong conclusions: Not everything is architecture. Everything is landscape. Whether built or non-built, whether urban, rural or suburban, whether with architects or without. Architecture is a subcategory of landscape. Everything is landscape that belongs in the best case to all of us – which is unfortunately not the case. Landscape is collective and landscape must be considered collectively. From that perspective I consider the thinking in islands and objects without integrating context and surroundings as very problematic. Only when we understand and act collectively, we can create a common process that leads to transformation.

With regard to architecture as a profession, I call for a fundamental change of professional attitude and working conditions. Working in our industry has so many advantages in terms of flexibility and in terms of time and place, and we should take advantage of that instead of fostering exploitation. I am strongly arguing for a 30-hour work week in general, especially as I may have employees myself one day. This is not just about more free time. It’s about dedicating time to other important things outside of architecture: to engage politically, in the community, for the climate, as a volunteer or otherwise to work on a personal project or vision. This could also help to establish a functioning balance of work and family with shared care work.

Architects always preach forward-looking, world-changing visions, but we don’t even manage to create gender equality or family compatibility in our own bubble.

I have worked on more than 50 architectural competitions and therefore worked many night shifts. The biggest success was winning a design competition for a neighborhood with several thousand people with a building volume of around 300 million Euros. We were the youngest team participating and no one expected us to win. The entire team was under 30 and we managed to complete this competition with almost no over hours due to good time management and structure. Competitions can be done this way if you want to and plan accordingly. The working-through-nights-and-drafting-one-night-before-submission tradition is a complete misunderstanding of the whole industry.

A few very specific things that can be implemented immediately:

- Stop leaving building stock empty and unused

- Stop to collect designated building land with no intention to build

- Stop to dedicate more building plots: each new dedication must be carefully examined to determine whether it is reasonable and sustainable for the future.

- Every flat roof must have a humus layer of min. 30 cm to store water and for a better microclimate and as a compensation for the soil sealing through the new construction.

- Sustainable development concepts – especially for rural areas – must be elaborated through a participatory process, pursuing specific sustainability goals and objectives for the strengthening of the specific region and local character, and accordingly promoted and penalized in case of non-compliance.

There is a lot to do! Let’s go for it...

How do you perceive yourself as female architect working in a male dominated field?

What I always found very contradictory in the architecture field was on the one hand the visionary appearance of the mainly male architectural icons only, from whom we learned in our studies. And at the same time the ultimate old structures considering women only in their role as caretakers for the family, and the superelevated ideal of the male architect work days and nights in the office. This disastrous image of an architectural office was burned into our brains. It should finally be forgotten, unlearned and completely rethought.

This is not only true for architecture, but also for other industries. The standard to which everything is aligned to is a male standard of living and working. Woman are always the exception of the male standard: having children is the exception, parental leave is the exception, nursing is the exception… It should be the other way around, because we need children for the continuity of our society. Women are still punished when they raise children, whether financially or professionally. Additionally, as a woman in this profession you have to fight much harder for your career than many male colleagues, because you are still not given any credit. I recently heard an interview with the singer of the Australian rock group “Amyl and the Sniffers“ – a very cool band. She pointed out that as a woman you always have it at least twice as hard. You are expected to be good and perfect, and you can’t just make trash music like many male musicians do.

The situation in architecture is similar. According to my experience, you have to make double and triple the effort to achieve something. As a woman you can’t afford to be mediocre, although many colleagues are mediocre or often even bad and still successful. I often ask myself what would happen if I were a man. Would the same thing happen to me, would I have the same opportunities and possibilities as a man? In a male dominated environment, it’s sometimes even more difficult if you are talented, ambitious or very honest and straight forward woman. Most of the time this behavior is perceived as annoying – when it is enacted by a woman. You are talked down to and discredited. How often I’ve heard that I’m cheeky just because I don’t always say yes and amen. The word cheeky alone, which is mostly used by men for women or by adults for children. But dear colleagues, I can tell you one thing, even if it is often very exhausting, tiring and grueling for me, I will continue to be “cheeky” and point out my opinion.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into?

- LAMA – a solution-oriented architecture magazine from Graz

- banalebanale.at: An exhibition format from architects for architects organized by the Zeichensäle of the Graz University of Technology

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

I would like to recommend everyone to be political and fight for a better future, everywhere and especially while studying architecture. No matter what the professors and teachers say. Explore architecture beyond the boundaries of the field. And overall: Don’t do architecture only. At the end of the day, doing architecture is just a job and there are many interesting things to discover outside of it. Therefore, enjoy life and don’t take everything too seriously. Do what you enjoy, because that’s what you can do best. And last but not least: do not fall for the trap of meritocracy (Leistungsgesellschaft) – show solidarity.

Project 1

ArchitektInnen und das Land – eine Kapitulation?

Masterthesis

Architects and the countryside – a surrender?

The relationship between architects and the countryside is ambivalent in many aspects. The discipline of architecture is not recognized and accepted as a needed professional in rural areas. Architecture in the countryside remains the exception. The subject of this master's thesis is the presentation of a general but subjective structure of perception by architectural practitioners, which is intended to further substantiate this relationship.

“The countryside is now the frontline of transformation.” Rem Koolhaas uses these words to describe the current transformation of rural structures. Since industrialization more than a hundred years ago, the traditionally shaped image of rural areas has changed. Digitization and globalization have seriously changed the structures of agriculture and ways of life. We focus here on the other almost 50% who do not live in urban areas. They are directly on the front line, as Koolhaas said, and are the ones directly affected and shaping this process of change.

The study deals with various stations. One of them is a big parallel between development of rural building culture and agriculture. The current building culture and the cultural landscape are directly related to each other. The traditional building culture from agriculture has developed independently without architects and through a culture of hardship and the associated landscape. However, what was previously locally sourced in the cultural landscape, what a local building tradition, a local building style entailed, can now be consumed from anywhere.

In the displacement of the traditional cultural landscape to an industrial and capitalistic one is the big challenge for architects to create a building culture that can persist despite the transformation and link to history to become and remain identity-forming. It is about understanding contemporary culture. To ask oneself what building culture can mean today, when it comes from a culture of survival and became a culture of abundance.

Bad Blumau

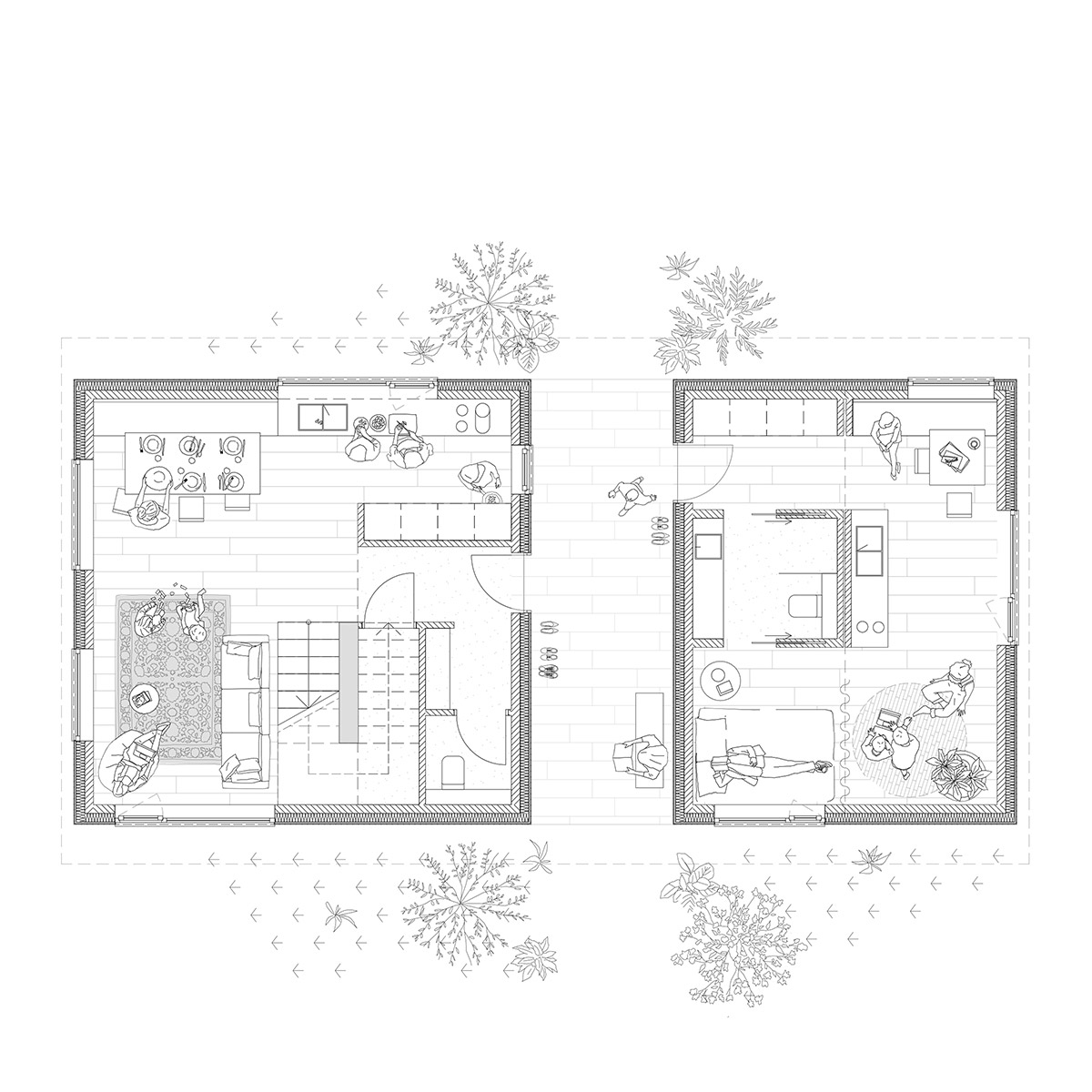

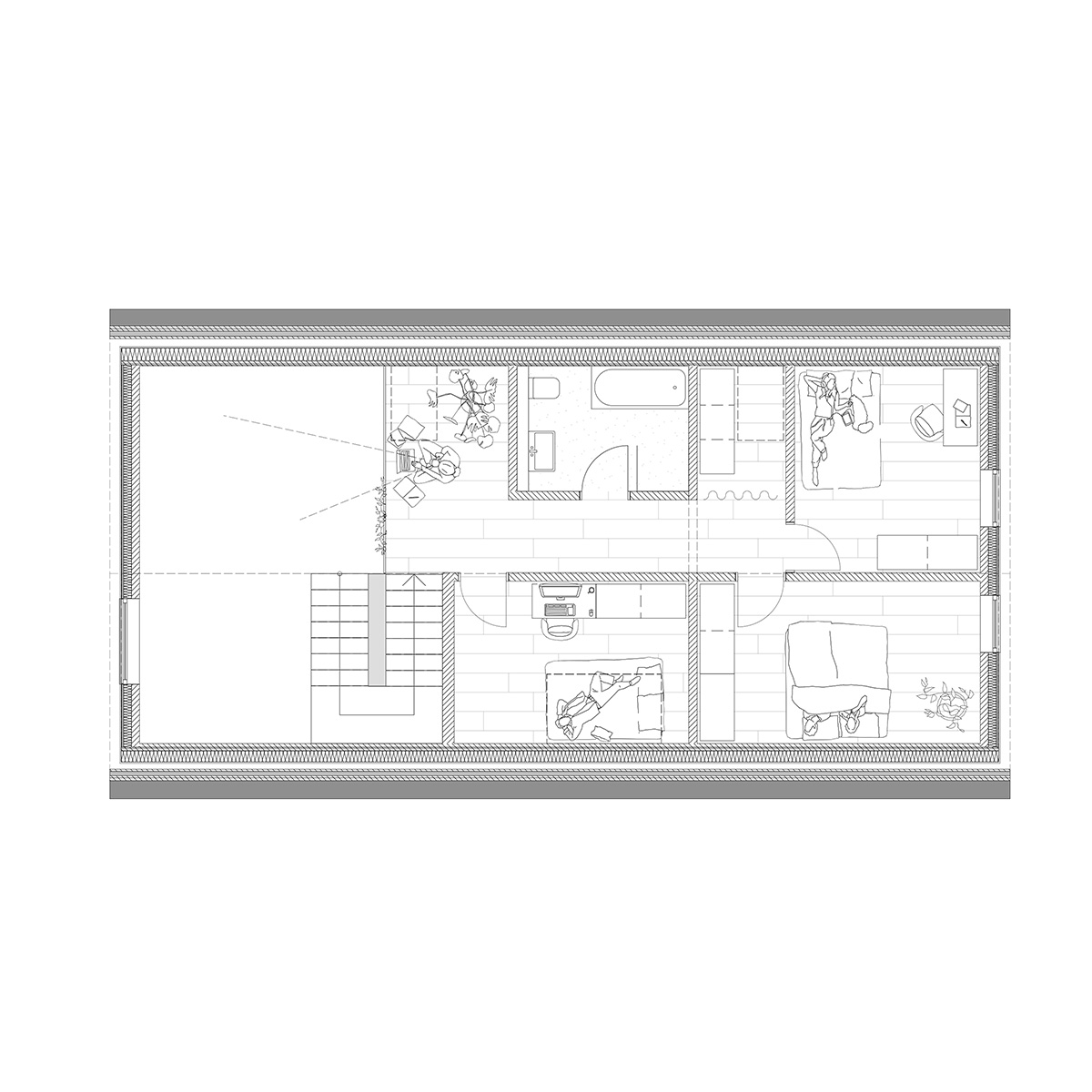

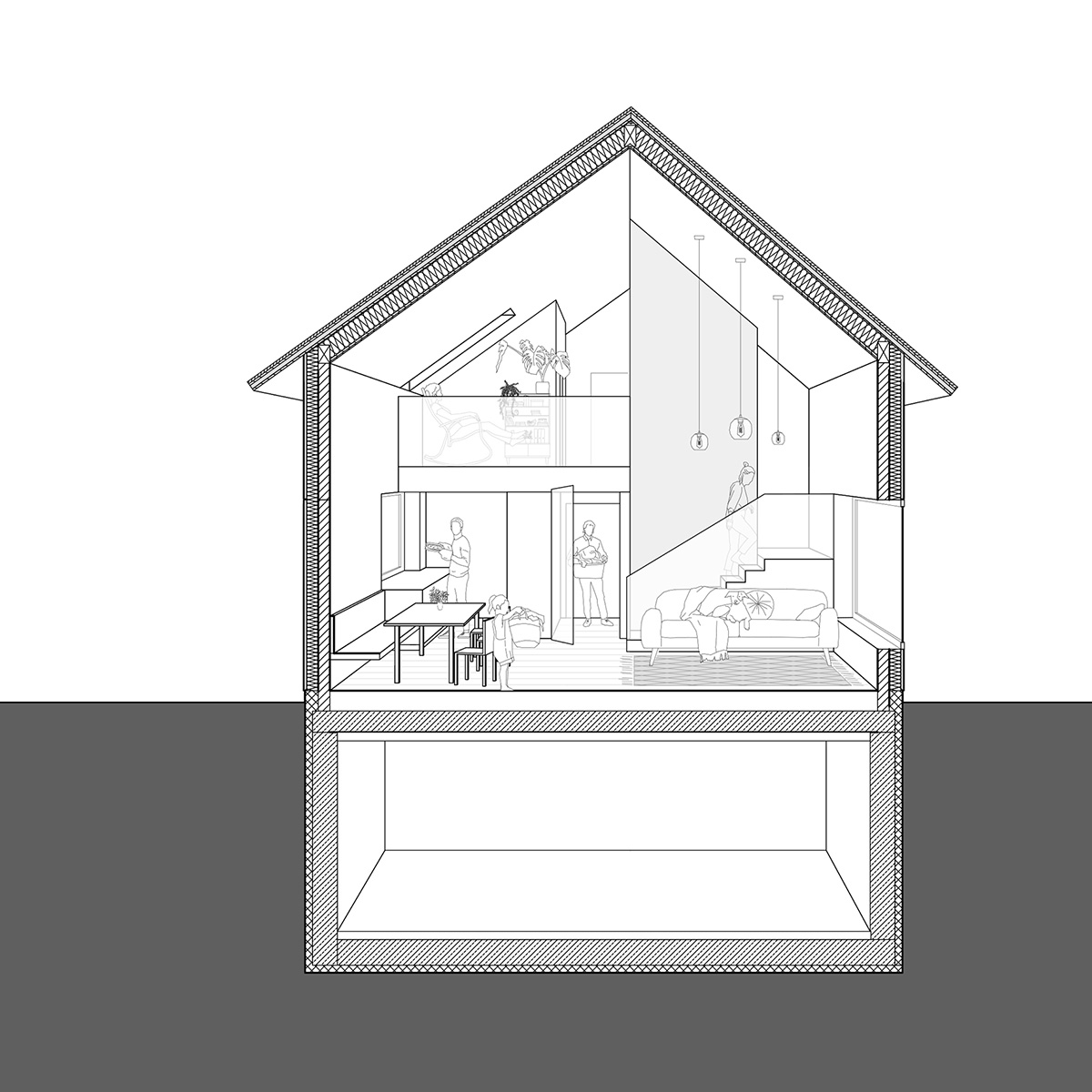

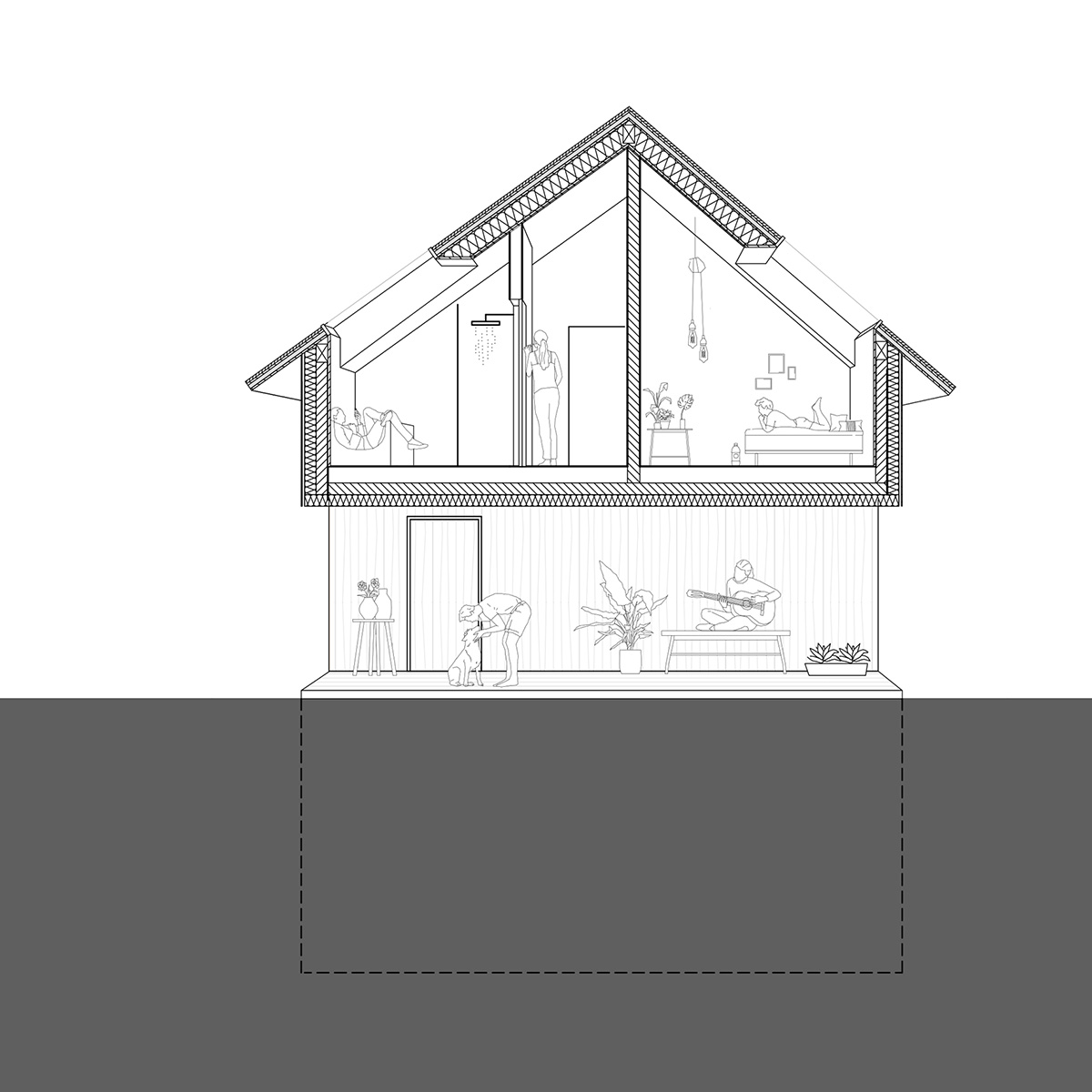

Project 2

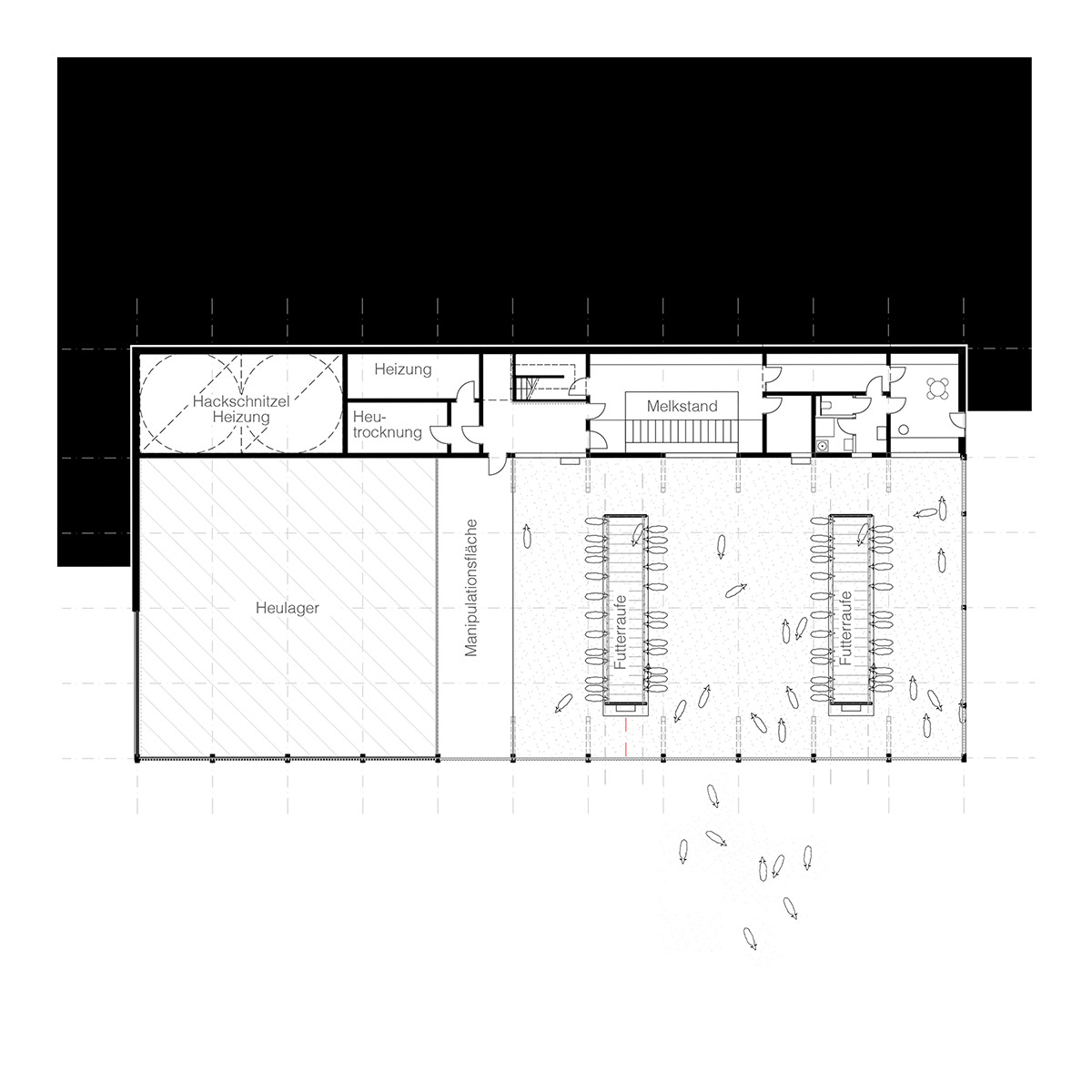

Entwurf einer Hofneugründung für eine faire, transparente und nachhaltige Milchschafwirtschaft mit Hofkäserei

Design of a farm start-up for a fair, transparent and sustainable dairy farming with a cheese dairy.

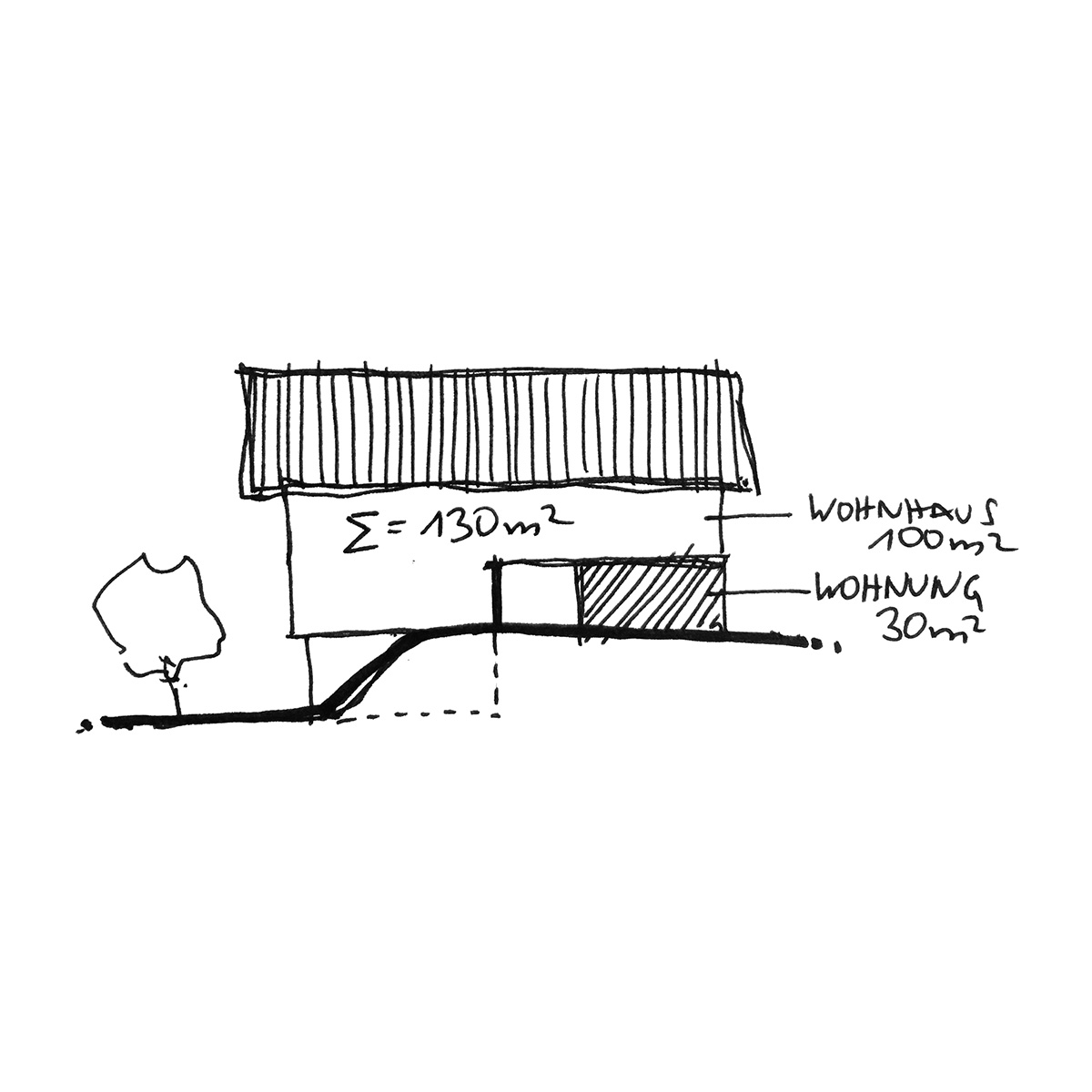

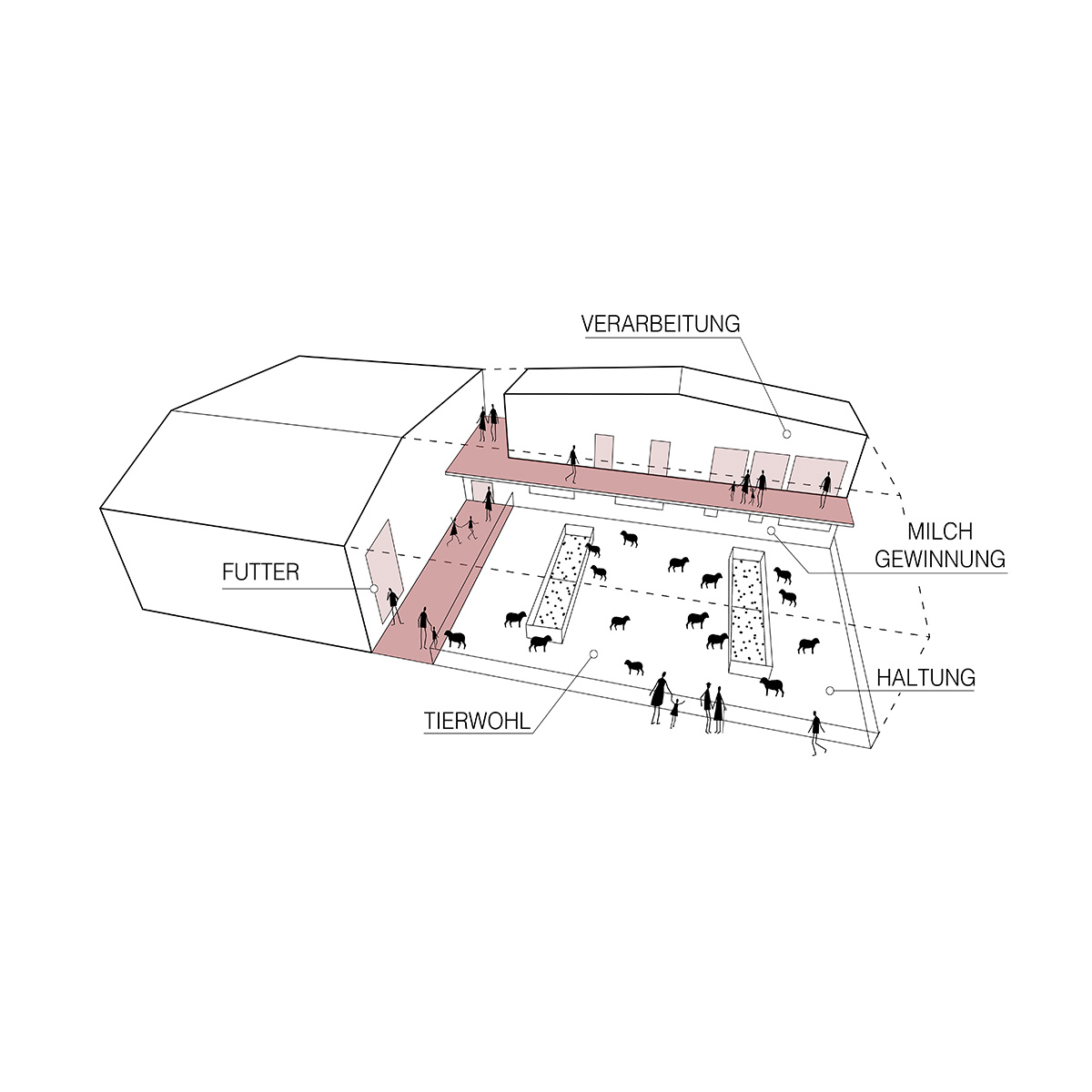

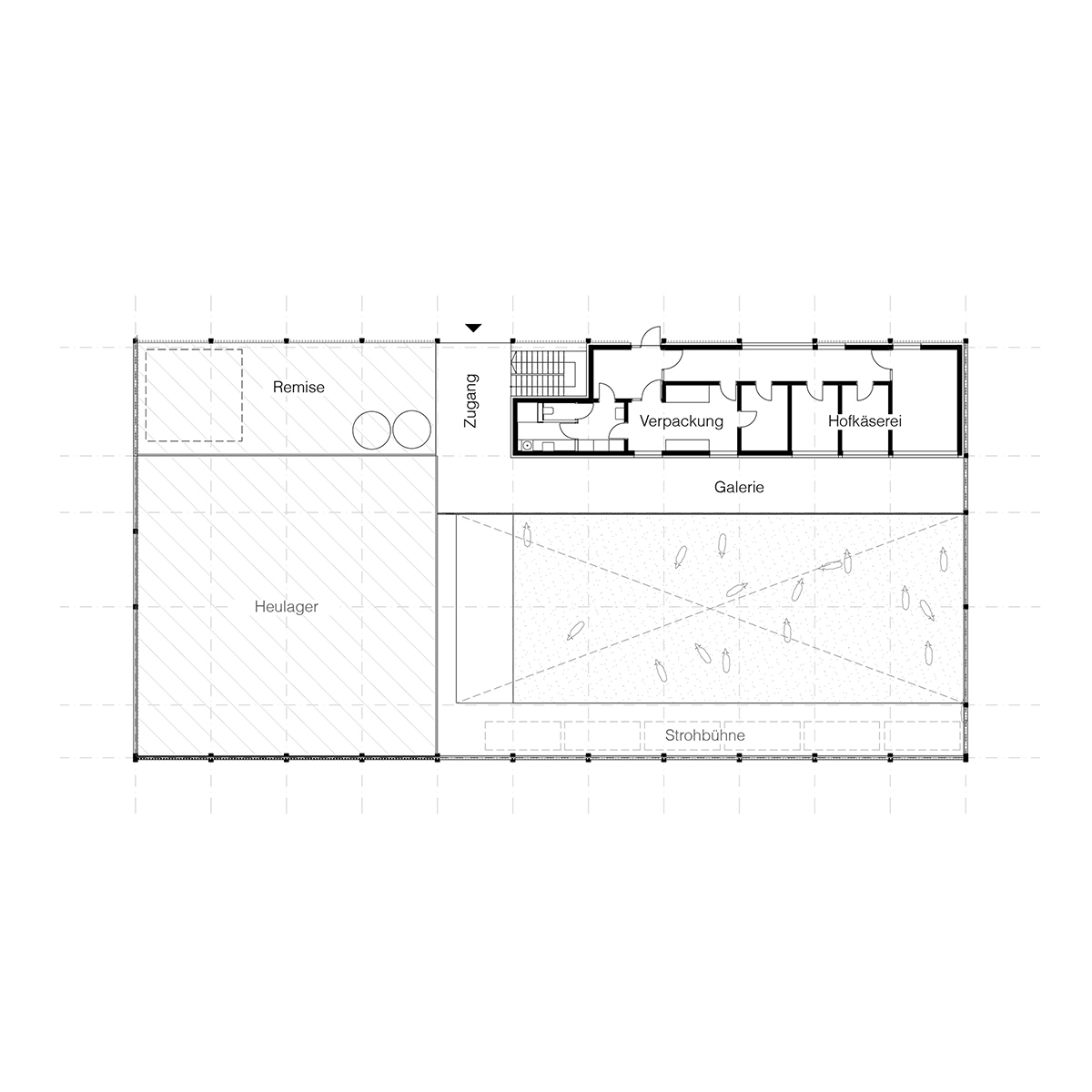

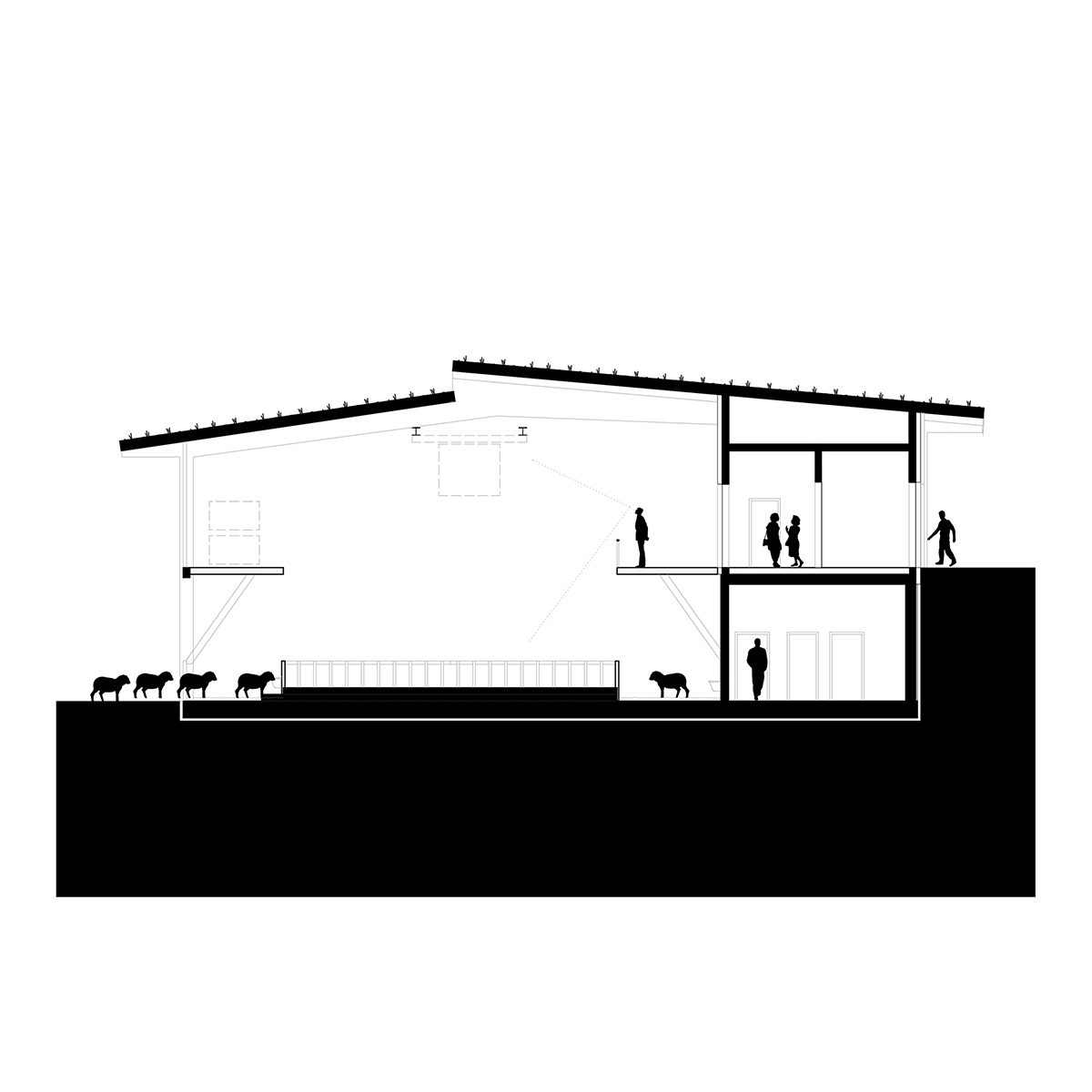

Continuing the topic of my master thesis, I would like to present here as a second project the design of a farm start-up. As mentioned, challenges also bring new opportunities in various fields of activity that have remained rather undiscovered until now. This also includes agricultural buildings. My claim to architecture is always an ideological one. Architecture never stands for itself alone, but can also promote and clarify a movement, a motivation, a point of view. This design shows a farm re-foundation with a stable building in which a farm cheese dairy and energy source is integrated.

Thus, the building functions self-sufficiently and the entire agricultural process, from the production of fodder, the keeping of animals, the extraction of raw milk to processing and tasting are transparently depicted. All processes are always related to each other, also visually. The consumer can follow every step of the process, see it, smell it, feel it and finally taste it. The architecture promotes this attitude of a newly conceived agriculture that strives for a fair, sustainable and climate-friendly treatment of animals and soil in order to produce high-quality food. Away from commercial, industrial food production. This point of idealism can be made visible here through the tool of architecture in the built environment.

House

Barn

Website: https://troublemaker-architecture.blogspot.com

Instagram: @supertomorrowarchitecture | @tre_a_f

Photo Credits: © Theresa Reisenhofer

Interview: kntxtr, ah+kb, 10/2021

Further Reading:

http://gat.st/news/stadt-land-und

http://gat.st/news/was-man-lernt-das-bleibt

http://gat.st/news/learning-vorarlberg

http://gat.st/news/kommunikation-mit-dem-land

http://gat.st/news/heute-morgen-und-ubermorgen

Website: https://troublemaker-architecture.blogspot.com

Instagram: @supertomorrowarchitecture | @tre_a_f

Photo Credits: © Theresa Reisenhofer

Interview: kntxtr, ah+kb, 10/2021

Further Reading:

http://gat.st/news/stadt-land-und

http://gat.st/news/was-man-lernt-das-bleibt

http://gat.st/news/learning-vorarlberg

http://gat.st/news/kommunikation-mit-dem-land

http://gat.st/news/heute-morgen-und-ubermorgen