22/013

ifa_diaspora

Student Initiative

Berlin

«The tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview.»

«The tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview.»

«The tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview.»

«The tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview.»

«The tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview.»

Please, introduce yourself and your project…

We are ifa_diaspora: a student initiative, platform, and safer-space of architects, planners and urban researchers at TU Berlin’s Institute of Architecture (IfA), consisting mainly of post-migrant and PoC students. Our overarching goal is to expose structural and institutional racism in the fields of architecture and the broader built environment. Starting at the IfA, we are primarily concerned with highlighting, questioning, and actively dismantling racialized hegemony in architectural teaching. We advocate for a more critical planning environment through sustainable and multi-perspective knowledge production within the industry.

Workshop-weekend, Summer 2021. © ifa_diaspora

What are your experiences founding your own Initiative? Why did you start your own initiative? What difficulties did you face?

This past year, we realized that a space at the IfA in which to safely voice critical, anti-racist, and decolonial perspectives on academic content needed to actively be claimed. Most of us took part in a seminar named “Architecture and Racism”. As PoC and Post-Migrant students, we shared common experiences, and reactions to the content and contributions of the participants amongst ourselves outside of class. Beyond the content of the class, we all realized that architectural academics and practice is severely influenced by structural racism that impacts us in the way we navigate our careers as students and practitioners of architecture.

Within architectural practice we hear stories of bosses declining applications because “Bitte, keine Araber”, and of fellow PoC and post-migrant architects being paid less or given less demanding tasks in offices. In academic contexts, we witnessed racialized comments from teaching staff and observed the reproduction of racist content without contextualization, commentary, or critical reflection at lectures in architectural history and theory, as well as in design-build courses. Across the field, we see a gradual decrease of representation of post-migrant and PoC students/architects from undergraduate students to professors or practitioners. While for some, these stories will forever be anecdotal individual cases “Einzelfälle” the observations of structural racism and inequality are an objective collective truth we experience, which we were never able to share or reflect on in academic contexts.

At the end of the seminar “Architecture and Racism” a few of our members had the opportunity to reflect on these contemporary observations of structural racism in a closing session. They chose to focus on the teaching of the architecture faculty at the TU Berlin naming the closing session “Open Forum: Racism and the Teaching of Architecture at the TU Berlin”. Through the Forum, they hoped to initiate a critical and productive discussion between teaching staff and students beyond the classroom walls at the official 2021 annual exhibition of the IfA, on the basis of a structured analysis of design-build, architectural history and theory courses. Unfortunately, the official slot was canceled from the program without any prior communication with the students. In a belated explanation, it was claimed that this decision was made to protect the staff and their work from being scrutinized as racist.

This moment of silencing – the active cancellation of the Open Forum – made it all the more clear to us that we need to start the conversation around the entanglements of racism, colonialism, and architecture. Furthermore, the cancellation highlighted the political power structures at play in universities, and how easily critical student voices are suppressed.

In response to these events, we took it upon ourselves to create the space for critical engagement with architectural teachings and the foundations of the discipline as a whole. We self-organized and led the Open Forum despite the official cancellation, and from this event on ifa_diaspora emerged.

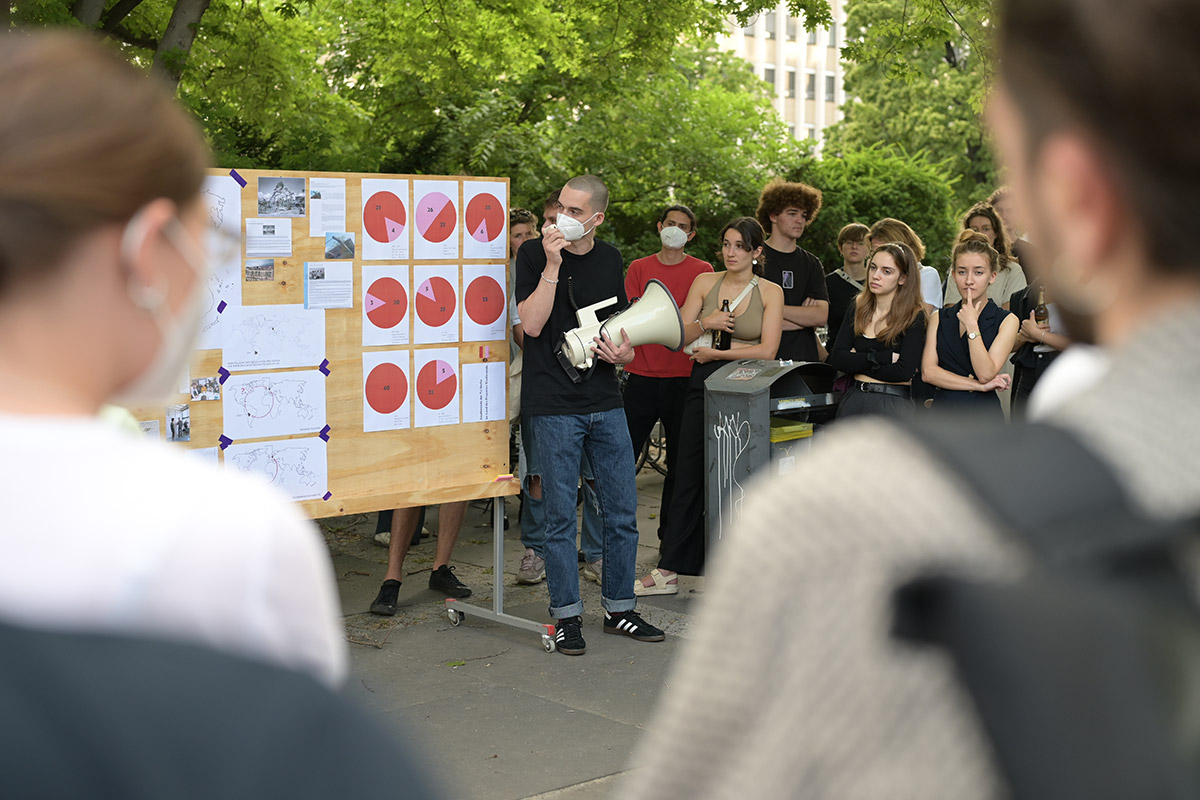

The Open Forum took place on the 14th of July, 2021 on the forecourt of the architecture building of the TU Berlin. Despite taking place parallel to the official program of the IfA annual exhibition, the invitation to come together, reflect on, and discuss teaching content drew a crowd of around 100 interested students, faculty members, and other members of the architecture community.

Poster Open Forum, © Renée Tischer

The tension that arose between students and faculty as a result of the necessarily subversive nature of the Open Forum set up a political environment that was characterized more by opposition rather than by a sense of collective interest and concern. This non-cooperative grounds for discourse were mainly evident through the defensive contributions of many professors, who tried to present their work as anti-racist by emphasizing their own international projects and teaching content – thereby evading the discussion and a critical examination of their own curricula.

Some faculty contributions nevertheless raised important points in response to student concerns, enabling political and public engagement which had been missing at the IfA for a long time.

Open Forum, © Merlin Ehlers (Image 1+3), © Leon Klaßen (Image 2)

How would you characterize architectural teaching at your university/at German universities today?

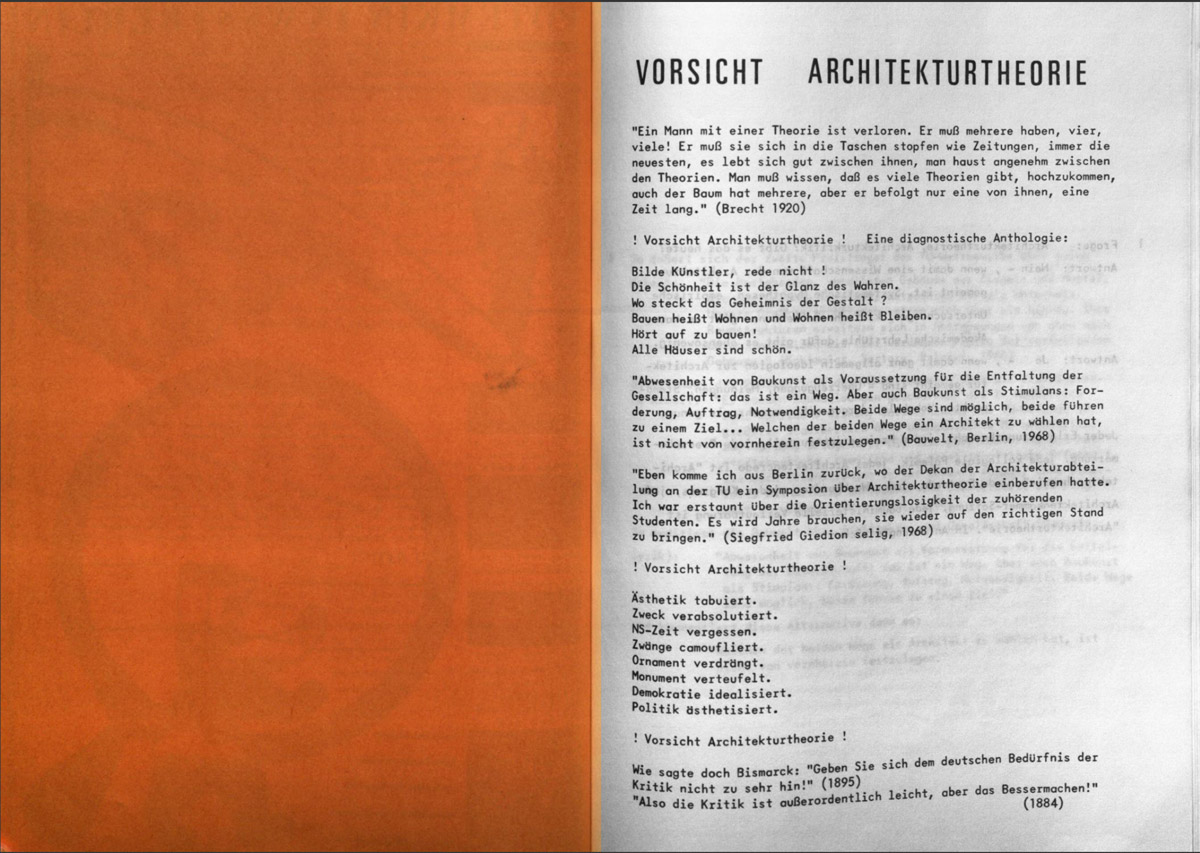

The Institute of Architecture at TU Berlin actually has a history of student activism dating back to the late 60s. In the wake of wider political unrest in what was then West-Berlin, a group of architecture students, under the name of Aktion 507, initiated a series of protests that aimed to restructure the academic values at the TU and to critique the technocentric and capitalistic tangent the field was taking. While it lacked intersectionality and a direct lens on the coloniality of knowledge and power, the activism of Aktion 507 centered around a critique of modernism, which we now see as integral to postcolonial discourse.

The group’s manifesto, published in 1968 on the occasion of the exhibition “Diagnose zum Bauen in West-Berlin”, also heavily critiqued the teachings of architectural theory at the faculty. The group famously raised banners in the architecture building of the TU that we occupy today which read: “Alle Häuser sind schön, hört auf zu bauen” (all buildings are beautiful, stop building), a call that many spatial practitioners have recently been echoing (one example is A Global Moratorium on New Construction

Aktion 507’s manifesto, published in 1968

If we look at the structure and organization of architectural studies at German universities today, it is striking that students’ political engagement and participation is not prioritized and is thus only possible with extreme difficulty or with the extension of one’s study period. This structurally conditioned hindering of students’ engagement with teaching content has led to a static and stale body of teaching in architectural theory, with the curriculum lacking critical reflection on and reference to contemporary cultural, social, and political dimensions.

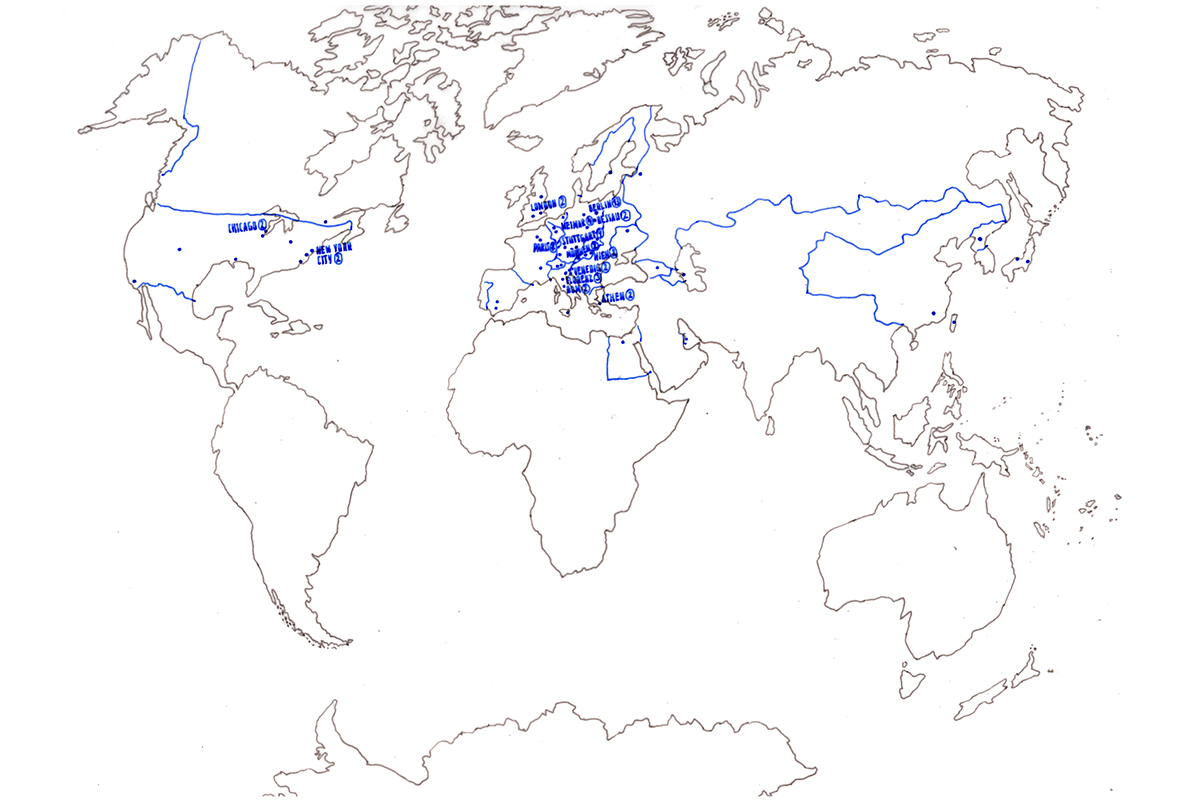

The scope of compulsory theoretical modules in the Bachelor’s and Master’s programs at TU Berlin constitutes a mainly European perspective of the modernist and postmodernist periods. Implied in the nomenclature of the department and its courses, “architectural theory” claims to be universal. However, a glance at the ideas discussed during the lectures shows an almost exclusive focus on the European context, while the overwhelming proportion of non-European architectures, histories, and epistemologies are forgotten or ignored. The correct name for the current subject is therefore European Architectural Theory.

Mapping of buildings shown at the architectural theory lessons, TU Berlin architecture masters program, summer term 2021. © ifa_diaspora

In a nutshell, this Eurocentric perspective ignores the fact that Western modernist architectural theory is informed by racist foundations. On one hand, the values of modernism and progress were the same ones that legitimized the actions of white Europeans in the form of colonization, robbery, genocides, and enslavement. On the other hand, modernist architecture was often a very powerful political vehicle in the commitment of the aforementioned crimes.

The structural erasure of non-European realities and systems of knowledge is based on the production and reproduction of racist values and is also reflected in the language of Western architectural theory and history: Banister’s Tree of Architecture divides the architectures of the world into different branches: of which only the trunk, which establishes a direct link between Greek and (US) American architecture, is future-oriented. Other branches of the tree die miserably. This thinking continues to shape architecture to the present day: Viollet Le-Duc’s writings combine ideas of social Darwinism with assumptions about the origin of architecture in the form of the “Aryan Urhütte”. Adolf Loos based his reflections on ornament as a crime in architecture on pseudo-scientific, racist assumptions.

What needs to change in the teaching of architecture according to you?

As we mentioned at the beginning of the interview, we center around a critique of the prevailing Eurocentric view of architecture taught at German universities. Eurocentrism in this sense is the reproduction of specific European ethnocentrism, where the evaluation of other cultures is based on one’s own learned cultural norms, behaviors, perception, thought patterns, and the assumption that these are superior. It is an effort to universalize European values while ignoring or destroying other forms of knowledge and of being. The dismantling of Eurocentric worldviews is especially urgent given the context of racism, ecological devastation, and global power asymmetries we live in.

Anibal Quijano’s theory on the Coloniality of Power argues that the legacies of colonialism have resulted in the corrupt social orders we face today, a main factor of which has been the dominance of Eurocentric systems of knowledge. Along the line of these arguments, we believe that justice in design and in the built environment starts with a dismantling of hegemonic systems of knowledge, making the university a primary site of intervention.

It is, for instance, no longer acceptable that the texts of Adolf Loos are reproduced without context or critique. It is equally ridiculous to address the history of architecture in 2022 as the legacy of white men from Vitruvius to Koolhaas. It should not be forgotten that gender has also fallen prey to coloniality, and as Françoise Vergès poses in Toward a Decolonial Feminism, decolonizing gender is an integral part of the effort to decolonize knowledge. However, it should also be noted that it is crucial for conversations around gender and colonialism to be truly intersectional and centered around subaltern epistemes, rather than once again around whiteness.

So, generally speaking, the tasks of academia today should include questioning the foundations of European architectural theory and education about the problematic origins of the European worldview, creating a multi-perspective environment that leverages the voices that have been suppressed by Western European and North American powers for centuries. The connection between colonialism and modernity should not only be an integral part of architectural theory teaching but should also be discussed in the supposedly practical teaching formats, such as the design-build projects which tend to be executed in formerly colonized regions.

What is your position towards Design-Build as a teaching format?

We welcome design-build as a teaching method that puts handcraft knowledge back on an equal footing with academic knowledge but ask ourselves why a) there is no theoretical discussion about the origins of this teaching method and the ideological approaches associated with it, and b) why German universities, in particular, prefer to carry out their design-build projects in former European colonies.

Image from the article “TU Studierende bauen für Indiogemeinden”, TU-Pressestelle, Juni 2000 © TU Berlin

Design Build was introduced at the IfA in the 1990s. The TU Berlin press office published a report about this in June 2000 under the title: TU Students Build for Indio Communities. A few people are shown to be working on a wooden building in a pixelated photo captioned “Wooden houses for Indios in the Mexican province”.

The structure of the sentence as well as the deliberate selection of the words used is by no means coincidental, it is rather a representation of social conventions which are based on racist ideas and are permeated by a white-saviorism mentality. White students, according to the official reporting, build for non-white people, in the spirit of a kind of development aid, in which there is a clear power imbalance between the developers and those seen to be in need of development.

For more on the “white savior” complex in general and the nuances of Western development aid, we recommend the instagram page @nowhitesaviors, and Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism.

Although the word "Indio'' has been eliminated from the reports on design-build projects in the global south, little has changed in the actual course of the projects at the IfA.

Diagram on bellavista.code.tu-berlin.de

The Bella Vista project, which took place in 2016, is one of the most widely published design-build projects of TU Berlin. These publications are mainly concerned with presenting the finished building as an aesthetic product that conforms to Western values. In regard to its design and construction, the attempt is made to present these processes as the result of an exchange between two equal partners. In reality, the transfer of knowledge was almost exclusively one-directional and took the form of a finalized design from Germany which already determined the choice of materials and construction techniques. The assumption that one could, in a kind of stroke of genius, design a building in Berlin for a village in Bolivia is profoundly “modern”, in the sense that a colonial form of knowledge is reproduced here.

The power asymmetries on which the project is built become visible in the representation of capital flows. Financing is transformed into social capital through the construction of the project and returns, in the form of cultural and symbolic capital as awards, coverage, and social recognition, to Germany, where it can be partially transformed back into economic capital. However, this cycle is only possible for the German side of the partnership; for the Bolivian participants, who are in an employment relationship with their German “partners”, the profit remains limited to the payment of wages.

The appeal of conducting design-build projects in the Global South among faculty and students is partly due to a search for something supposedly exotic. Yet, from the perspective of a white German student or teacher, these projects are always associated with living-out white privileges. This circumstance is discussed in very few cases. Also, the examination of socio-political topics, which should form the theoretical basis of every project, is largely disregarded.

In the spirit of the mentioned arguments, we as ifa_diaspora initiated a roundtable discussion in October 2021 at the DAZ (Deutsches Architekturzentrum), where we talked with Alesa Mustar, Prof. Ursula Hartig, Dr. Nina Pawlicki, Lorena Burbano, Sebastián Oviedo and many participants from the audience. 30 years after the first design-build projects, this was the first public event in Germany where students and teachers discussed design-build as a teaching format in relation to its (post)colonial entanglements. This should change in the future, a critique of new projects and a critical revisitation of already built projects is essential to effect a change in the future of design build practices.

DAZ Talk “DesignBuild in architecture - between ambition and reality”, © Leon Lenk Fotografie

What projects are you working on currently, and in which formats?

We’re excited to conduct a student-led class (Projektwerkstatt in German) that started this summer semester at TU Berlin. It functions as a seminar where we invite other students from any discipline and background to engage in an environment of co-learning and co-authorship. Our aim is to embrace the multiplicity of our different worldviews in constructing counter-narratives around spaces with colonial heritage in Berlin. We see it as a chance to theoretically and practically tackle some of the very entanglements we have been missing in the teaching content, and to progress from a critique of academia to its constructive co-creation.

Another initiative we have just started is to set up a shadow library at the IfA. The IfA library is currently missing countless highly relevant and contemporary titles on the intersections of racism, colonialism, and architecture. Attempts to have the library acquire new titles have insofar yielded no results. The shadow library would be open-access, allowing all interested students to engage with such critical and necessary knowledge. The aim is to create a space that encourages collective discussion between students and teachers.

We have also been running our instagram page (@ifa_diaspora) since our foundation and see it as a platform to directly connect with the community and to spread awareness on various issues. We are currently in the process of organizing a lecture series on racism in the fields of architecture and urbanism, for which we reached out to our follower-base on Instagram. By asking for suggestions on active voices relevant to the theme, we aim to co-curate this series with the wider community.

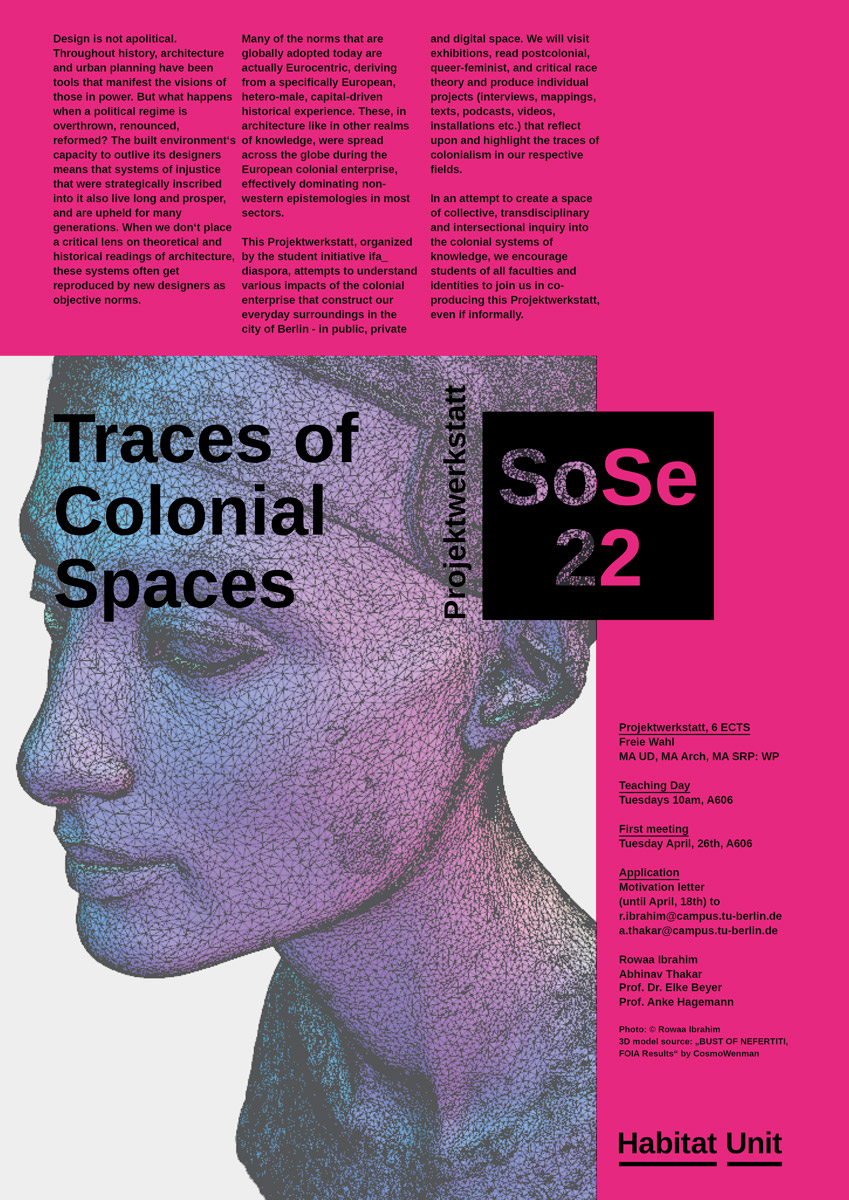

© Rowaa Ibrahim. 3D model source: "BUST OF NEFERTITI, FOIA Results" by CosmoWenman.

Name your favorite …

Book/ Paper:

- Race and Modern Architecture, Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, Mabel O. Wilson

- Weltkonstruktion, Sascha Roesler

- A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education, Wai Architecture Think Tank

- Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity, Fabiola López-Durán

- Wozu Rassismus, Aladin El-Mafaalani

- The location of Culture, Homi Bhabha

- Can the subaltern speak?, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

- Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism, Ananya Roy

- Invited and Invented Spaces of Participation; Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South, Faranak Miraftab

… that was influential for your work as a group/movement.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

Groups/initiatives/individuals:

- Dekoloniale Erinnerungskulturen in der Stadt

- AIAWD Podcast

- I.D.A UDK

- Mariam Kamara, principal of atelier masōmī

- Office Hours by Esther Choi, a knowledge exchange platform for BIPOC design students & practitioners

- DAAR - Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

The study of architecture remains largely flexible in its scope, varying significantly between different geographies and academic institutions. It’s therefore important to note that students of architecture have a great influence on the course of their own education by investing themselves in topics and worldviews that are of personal interest to them.

In light of Freire’s views on critical pedagogy, teaching should be understood much more as a collective and discursive process, rather than receiving instructions from a professor. We therefore encourage all students to stay critical during their studies, to question the power dynamics within teaching, to discuss collectively, and to take up the space to voice their concerns when it is not actively given to them.

A professor who smashes models is not cool; they are disrespecting your work. A teaching assistant who glorifies night shifts is simply in the wrong. A guest critic that criticizes your habitus, your appearance or your language, has no place in a university and is the reflection of a certain toxicity that is present in the architecture field. Architecture students should learn to question these dynamics instead of reproducing them.