22/009

Bernd Schmutz

Architect

Berlin

«I enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short.»

«I enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short.»

«I enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short.»

«I enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short.»

«I enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

I have founded our studio Bernd Schmutz Architekten in 2016, after having relocated from London where I previously worked for eleven years with Caruso St John Architects as one of the partners in the London office. Here in Berlin, we are working on a range of projects and welcome everything that comes on our table: projects in the city, on the countryside, transformations and new-build. Public and private, from furniture and exhibitions to landscape-scale, heritage or suburban context, the more different the better it is.

Parallel to the work in the office I am teaching. After Kingston University and LU Hannover I am currently teaching as a as guest professor at TU Dresden. I am also researching housing, with Jaretti & Luzi’s work from the 50–70s in Turin, which we will be publishing soon as a book, co-edited with Dominik Fiederling from Zurich.

How did you find your way into the field of architecture?

Having grown up on a farm I was surrounded by building and building sites which was exciting. There was always something that got built – sheds, silos but also little hideaways in the woods. The farm was a loose gathering of large and small structures, very diverse. As a whole it felt like a miniature village changing over time, a rich and complex world on its own and fantastic to grow up with. Eventually the farm also got taken over by regional artists and became the background for an art exhibition in the stables and barn. This triggered a few things and I got into drawing and art, so I guess this mix brought me to study architecture at Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg. My first internship at Otto Steidle’s office in Genter Straße made me aware of the connections between farming and architecture and kept this interest in landscape growing.

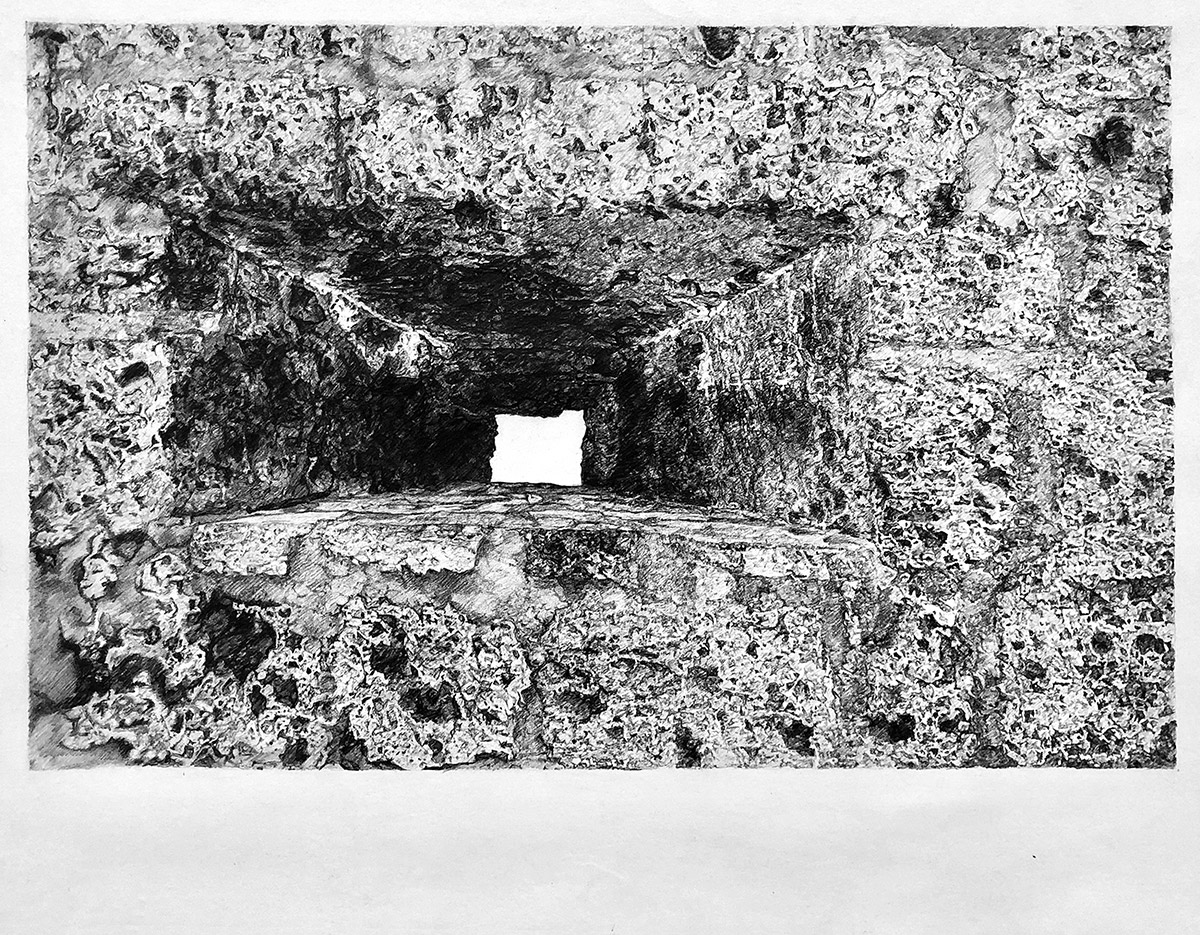

Drawing of a farm-house wall, Bernd Schmutz, 1996

Luckily with our project in Garkau we now find a situation where it’s possible to expand these early interests in different scales and to investigate new ways of living on the countryside. Hugo Häring’s architecture, that we are rethinking there is very diverse, full of life and therefore in the best sense sustainable, even though the rural environment around it changed a lot.

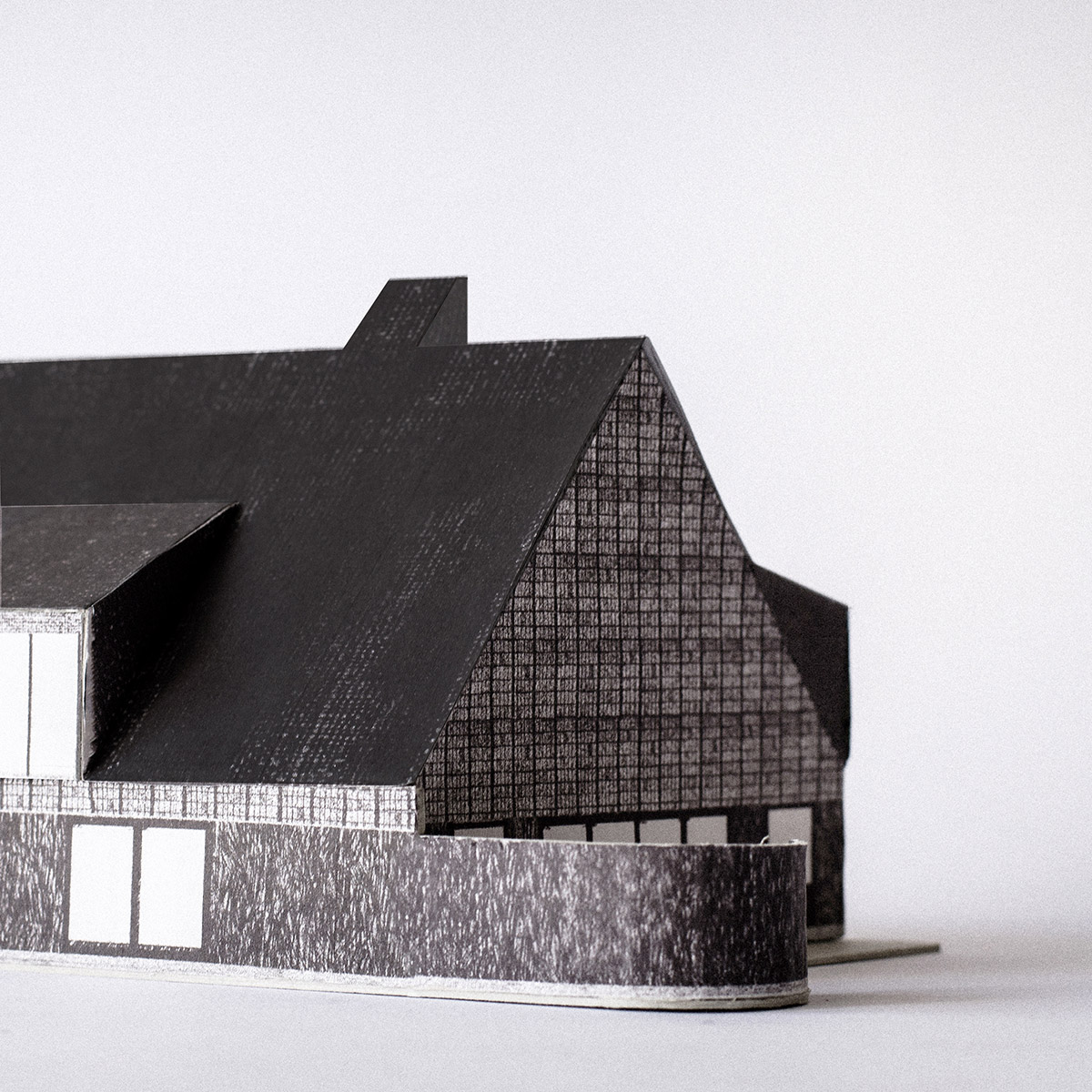

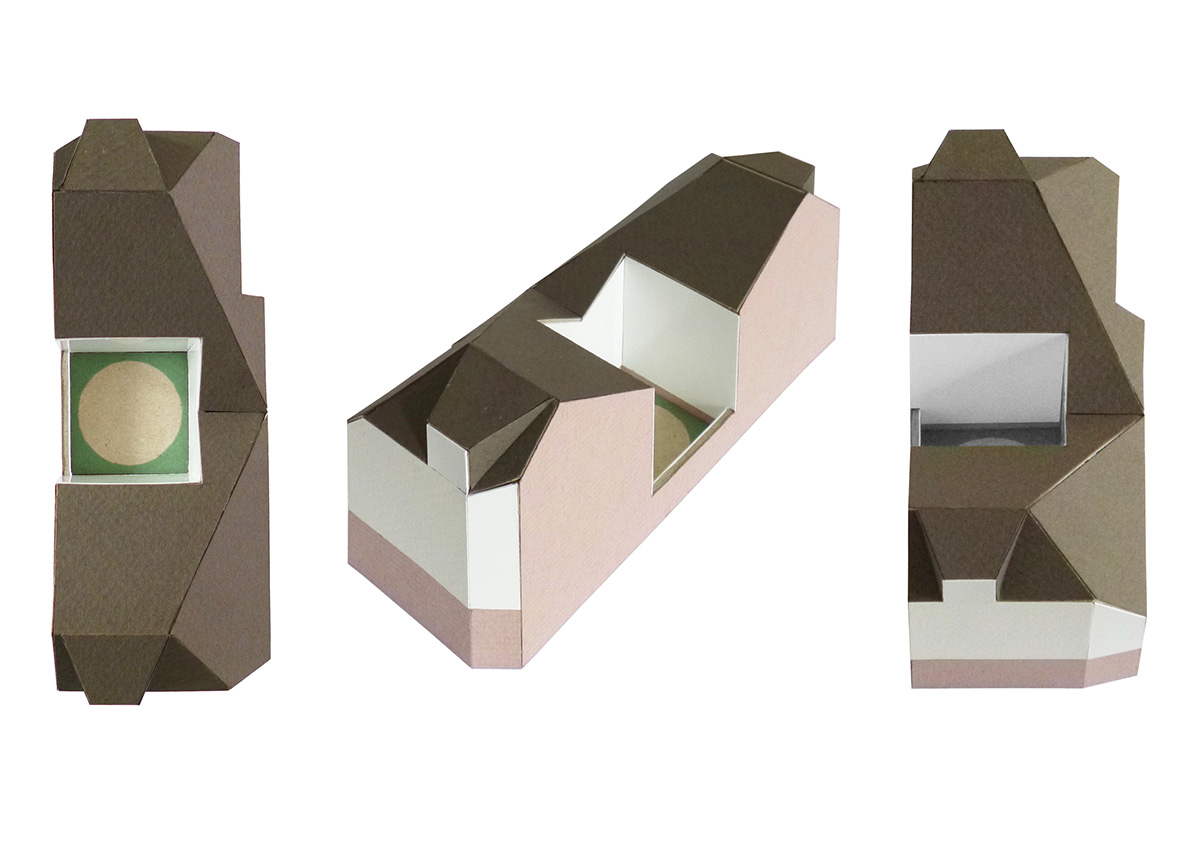

Model for a country-house with co-living, 2021 © Bernd Schmutz Architekten

What are your experiences founding your own practice and what does it mean for you?

I started my own office rather late, but I am grateful for the experiences I gained with Adam Caruso and Peter St John, a time that really stimulated and challenged my own way of thinking but also gave me the chance to take over a large range of responsibilities and to get an insight of how an office is run. During that time I also had the opportunity to start teaching which is something I continued since then and generally helps to keep the discourse lively, to reflect one’s own position with more distance and to see beyond the routines of daily practice. Surely this also nourished an appetite to unfold these thoughts with my own office.

Running an office has many aspects since the design of buildings evolves in different manifestations, as drawings, models or cost calculations and especially in a smaller structure these topics are spread across the team to nourish the process. Ultimately it is of course exciting to see the actual output as a building. But most intriguing is how it interacts with the world around us, when inhabitation starts. Since I studied in Vienna, I was fascinated by Hermann Czech’s work. Back as a student in Hamburg I did my first project with Dominik Fiederling, a suite of offices at HfbK which we then got photographed by a fellow photography student after people moved in to document these initial traces.

What does your working space look like?

We are working in a generous former flat which brings flexibility for how the office is organised but also in terms of sociable environment with a big kitchen for healthy lunches and a sunny balcony. The large shelf behind us serves us a reservoir and background, it is full with books, some art pieces of artists I admire, drawings by us and by friends, models from recent projects. It changes over time but is always a cross section of what’s going on.

What is your favorite tool to design architecture and why?

We try to keep our tool-box open, use pencil, models or 3D-CAD but apply them consciously depending on what we want to explore or say at a specific moment of the process. The tools allow different ways of thinking, they complement each other but do not substitute one or the other. A pencil supports design as an iterative process as there is never the one genius drawing. Both the process and tools need to have enough slack, to let the design find the balance between conceptual rigour and looseness, to enable different scenarios as part of the same framework of ideas. Whenever we can we use models, they are part of our physical world and allow us to be very close to our ideas.

Is there an essence of architecture for you personally?

I like things that are varied and complex, tolerant to take on other aspects, buildings that overlay contradictions. So, an essence is hard to grasp, I prefer findings that are at the same time both specific and generic. This requires seeing things in differentiation and giving space to any constraints as a chance to move on or to turn corners. I therefore enjoy seeing each project anew, aiming for diversity rather than cutting things short. As an attitude this is much healthier and more satisfactory for me, it enables critique but also being constantly curious and reflective towards the world around us. I am not interested in developing a signature handwriting and the architects I admire mostly did not do this either. An essence that may seem relevant today is likely to be out of date tomorrow or in a different context.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you?

Here in Germany I generally miss open-mindedness and curiosity to allow for new positions in architecture. Younger like-minded offices struggle to engage with open competitions and are limited to special constellations with particular clients and luck to be able to become part of a system which is rather passive, inert and conservative. However, a new generation of offices is very engaged to question this and slowly takes over more ground to make the debate political, lively, and dynamic – just like in most other countries. Challenging conventions is interesting but does not mean conventional. We do not want compromised “Mittelmaß” to become a virtue for architecture. The discourse therefore needs new and more varied voices to advocate an architecture that is both ambitious and close to its users.

More specifically I think that besides obvious deficits in rural areas, currently a careful focus is needed for inner city centres, showing strategies of transformation in different time-scales. With our students at TU Dresden we are looking at the city’s core to transform a very large existing building, a “beige elephant” at the heart of the city. With big and small interventions instead of the usual tabula rasa, by adding back programme with architecture that makes use of what is there, which is malleable, beyond the hermetic discussion of either historic reconstruction or modernism – a more nuanced attitude to embed existing and new structures in a world between climate change and online shopping.

Who was inspiring and influential for your own work?

This would be a rather long list of people from past and pesent, who I met but also whose work I experienced by travelling or books. And there are always new ones, e.g. some years ago I came across Jaretti and Luzi’s work in Turin and got to meet Sergio Jaretti. These architects were humble, yet constantly curious and found many ways to respond to the needs of their time in the form of housing schemes, all formally different and built between the mid 50s and mid 70s in Turin. This was a time of mass construction, but they were operating beyond the dogmas of modernism.

They had set-up their own office right after diploma and with some luck formed an enduring coalition with a loyal and supportive client who also acted as a contractor, so as a team they were keen on realising new forms of housing with a framework that is spatially generous both for shared and individual spaces and embeds much of what we ask for today.

As part of the work for our book we have met the residents who were all proud of where they live and invited us into their flats, enthusiastic about the buildings the architects conceived more than 50 years ago which is a quite rare view from a user-perspective.

How do you communicate/present Architecture?

We enjoy finding a specific way of formatting architecture in relation to each project and situation, so it’s a meaningful but also fun and playful part of the office work. There are interests that we follow but no fixed recipes or techniques. I like exploring new things, sometimes inspired by art, but the format also depends on the particular skills brought in at the time by members of the office which keeps the output dynamic.

Of course, models are a key to unfold our ideas but also a successful tool for communication, less hermetic than a rendering. We therefore enjoyed contributing with models to exhibitions like Alternative Histories and last year’s Belgian pavilion at the Biennale.

Through social media the modes for perception of thought and built architecture have of course changed, on one side with platforms like Kontextur who are stimulating debate but on a more general level with the internet also supporting those who are loudest.

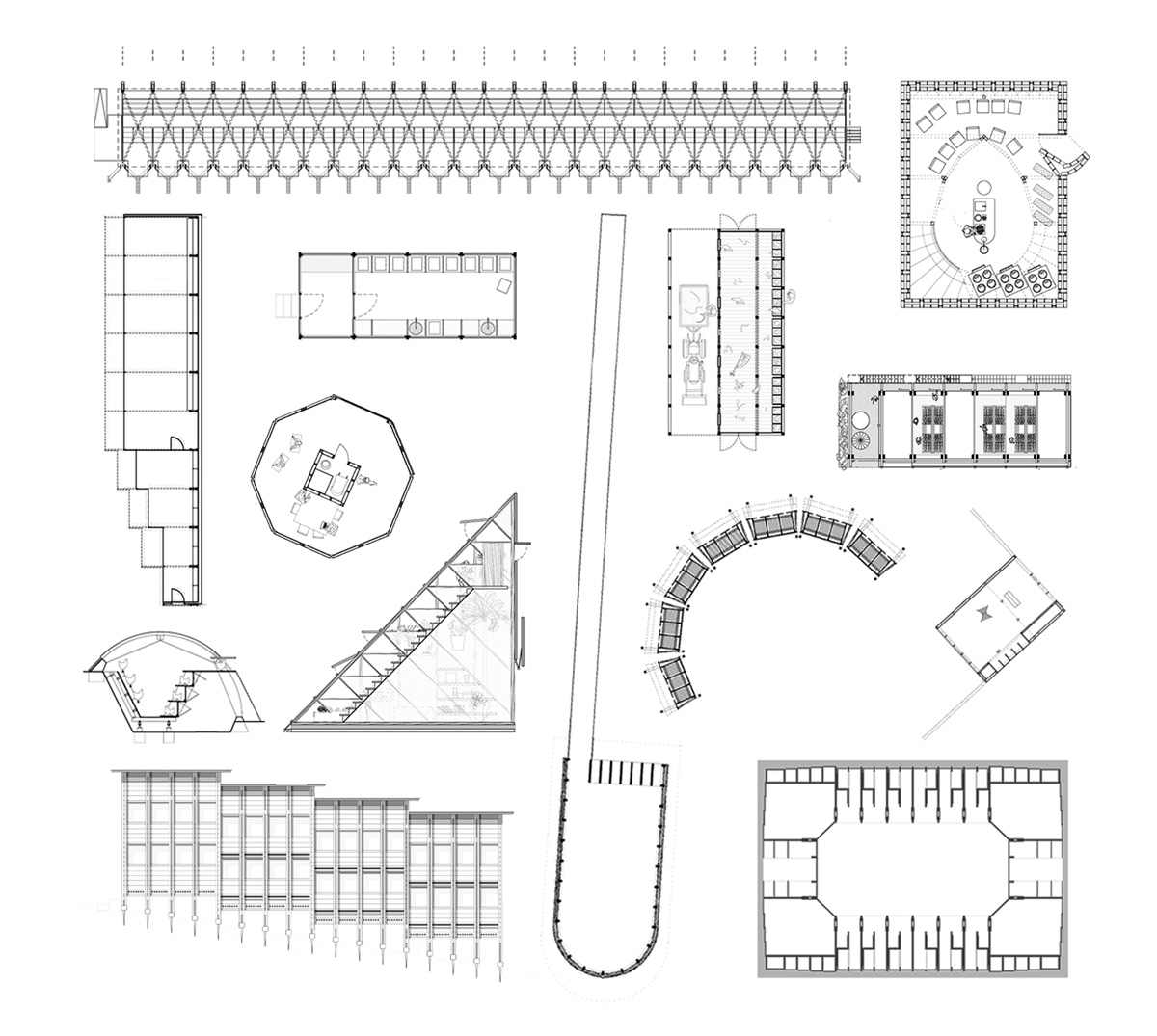

Venice Biennale, Belgian Pavilion curated by Bovenbouw, contribution with a 'Capriccio', 2021 © Bernd Schmutz Architekten

What would you recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school?

Strive for eagerness – both in making, being as productive as possible, but also cultivating an attitude rather than formal interests, one that is constantly curious and open to engage with the environment that is around us in all possible ways. Seeing architecture as an open and rich field that is altered constantly, responding to what is there, our immediate realities and needs. Challenge yourself and your tutors, so the discourse is two-way.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

Of course, I should name and promote our book on Jaretti Luzi’s work in Turin. Their architecture is now as relevant as 70 years ago but never had the presence it deserves which is what we want to change. The two architects formed a body of work over 20 years only but the impact of these buildings is much broader than that. They are all different, and can’t be put into any boxes which is a quality I admire, they withstand the fashions of time but respond in new ways to basic needs. Their architecture is extremely generous and offers a lot. The book is the first monograph focused on their housing projects. It will be completed soon and hopefully will raise the interest the architects and their buildings deserve.

Project 1

West Hill

London

2015 – 2020

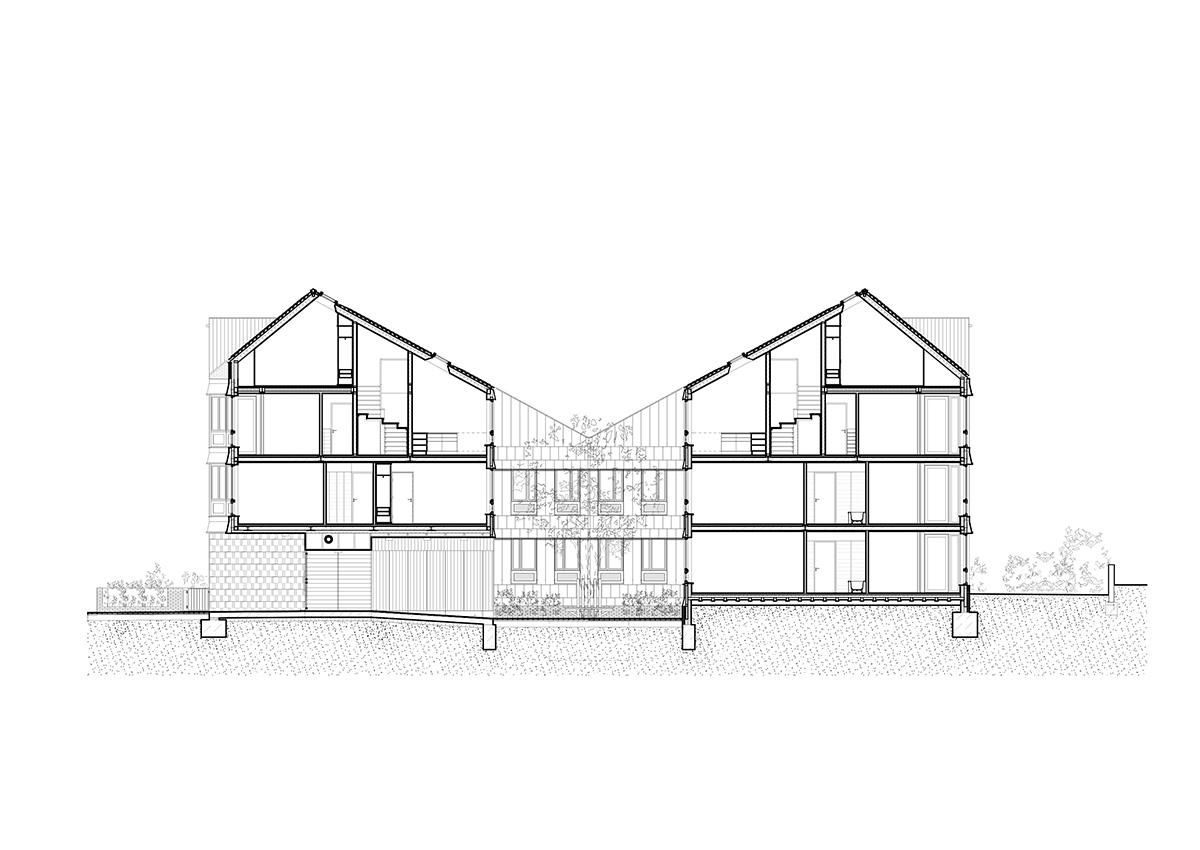

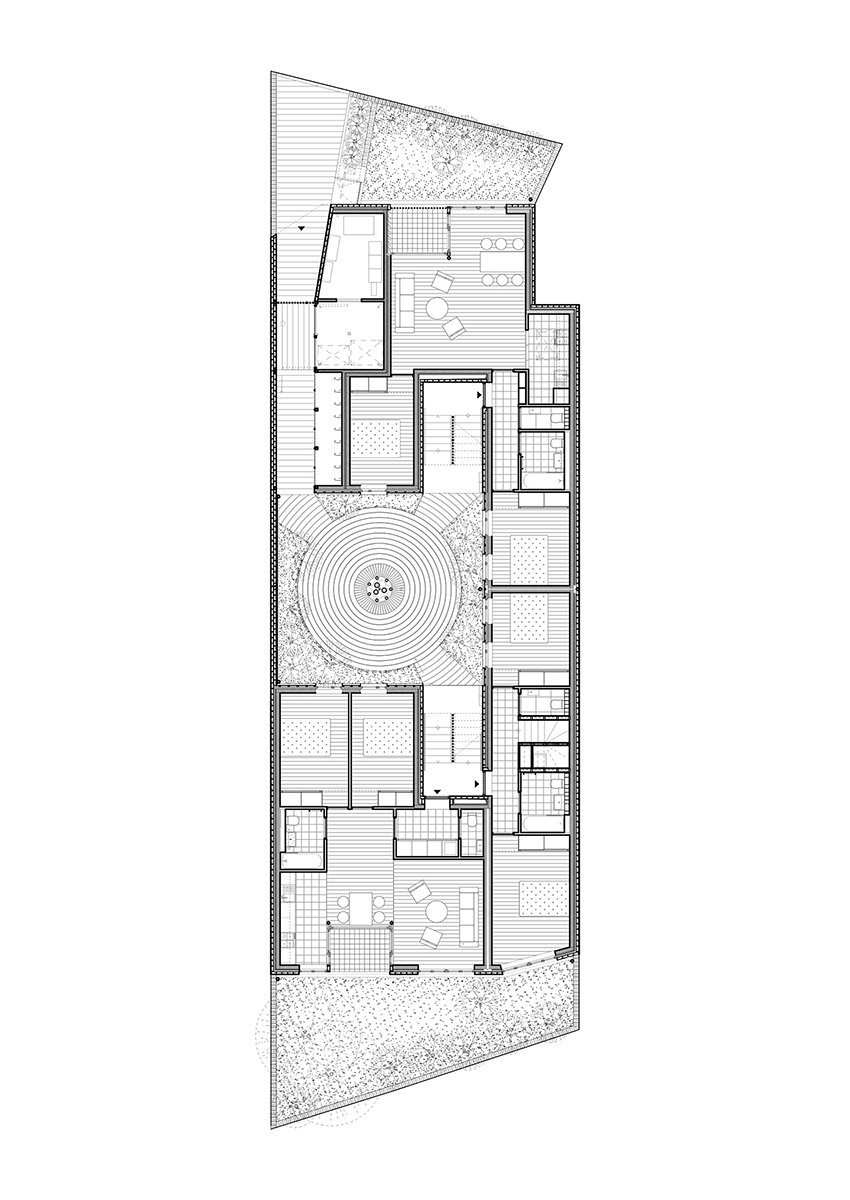

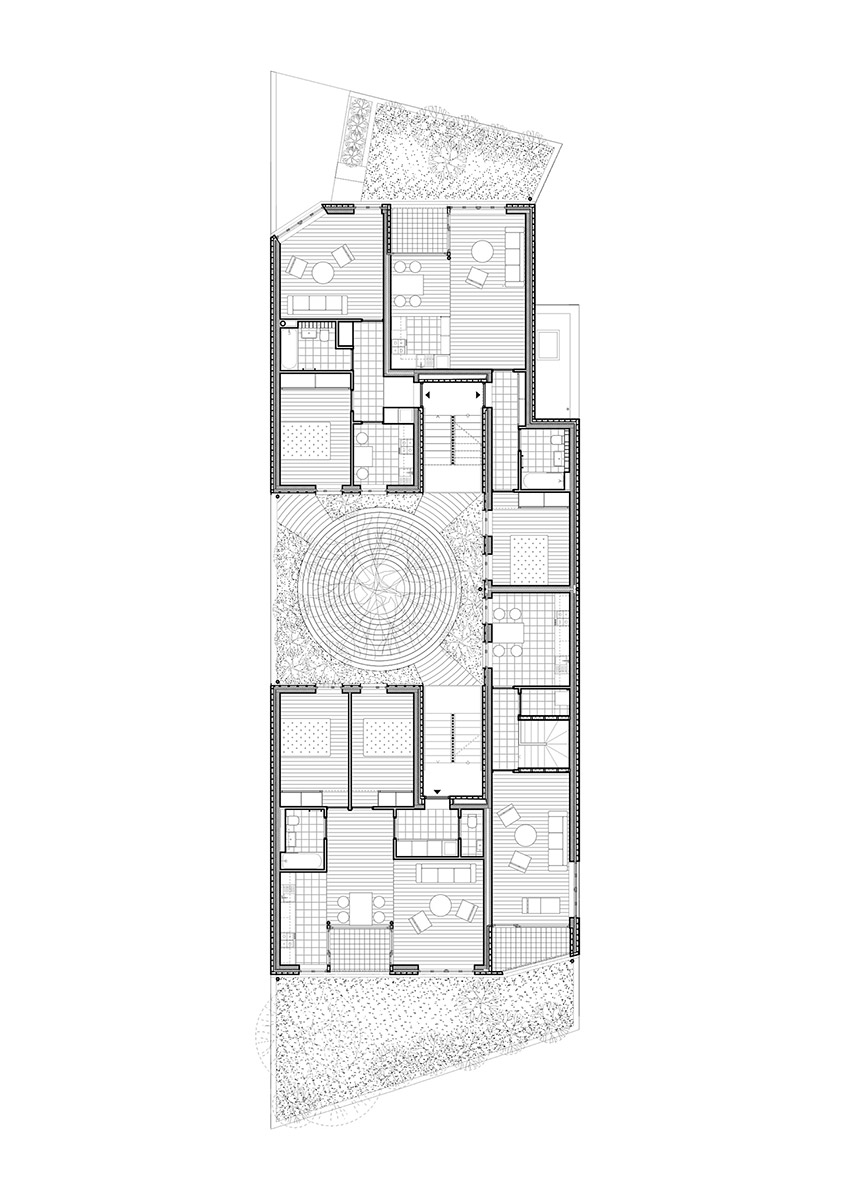

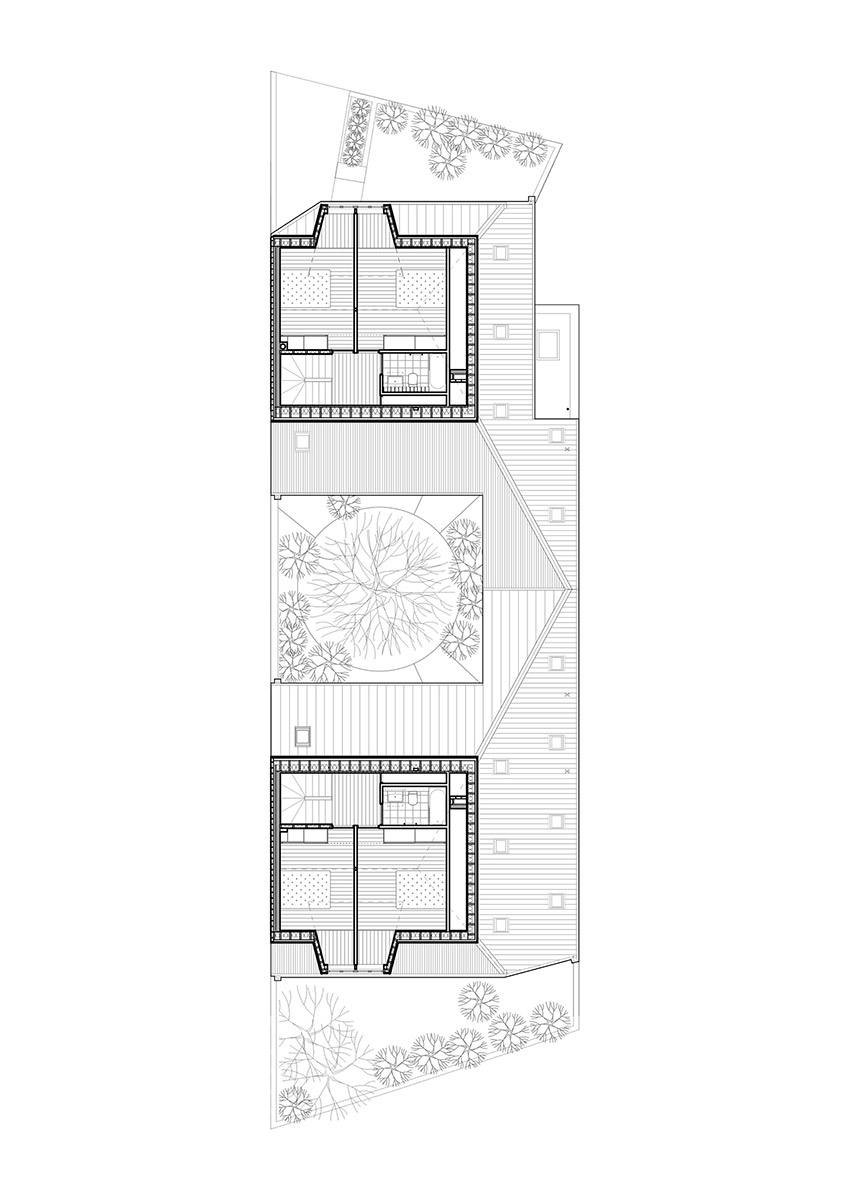

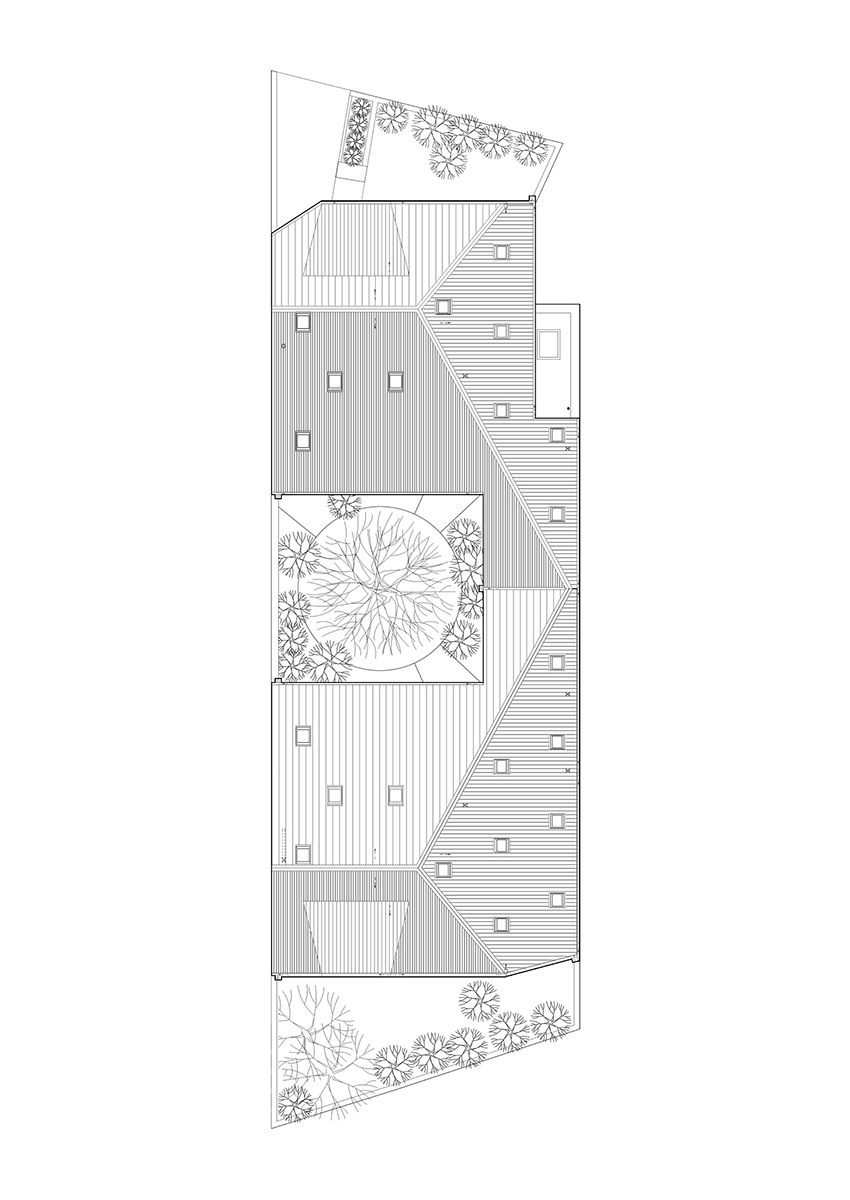

With Wandsworth’s untamed towers looming in the background, the scheme transforms a left-over piece of the city into new dwellings. Rising between the noise, the new-build miniature apartment block has been arranged amidst two heavy-traffic roads and around a planted courtyard with a silver birch tree. This inner core serves as a release from the busy streets, offering a quiet and dignified way for entering all flats from a green foyer shared between all residents, but also distributes light generously into the bedrooms. The airy and calm centre is surrounded by leafy, paneled facades and mirror-glazed windows to provide privacy but also reflect foliage.

A composition of large roofs around the patio echoes the language of the adjacent listed building but at the same time offers extra space for individual interiors with double-height rooms on all floors. Each flat has its own entrance door and a roof, with the benefit of increased ceiling heights, giving a house-like quality to each unit, which are all held together by one large roof.

The layouts of the apartments translate the constraints of the site into particular plans, all different with dual or triple aspect, stretching between the streets and the calm courtyard. A glazed loggia at the centre of each flat serves as a small garden room bringing daylight deep into each layout and naturally organising the semi-open plan with spacious connected living-kitchen-dining areas.

The facades transform the colour and material palette of its context into a calm horizontal organisation of cills, windows and terraces while the composition of gables, roofs and dormers connect the proposal to its Edwardian neighbour to form discrete yet varied facades. The first stage of the project was in collaboration with Emily Greeves Architects.

Project: Apartment block with 8 no. flats and maisonettes

Landscape architect: Hahn, Hertling, von Hantelmann

Location: London, 2015 - 2020

Photography by David Grandorge and BSA

Project 2

Troisdorf

2019 –

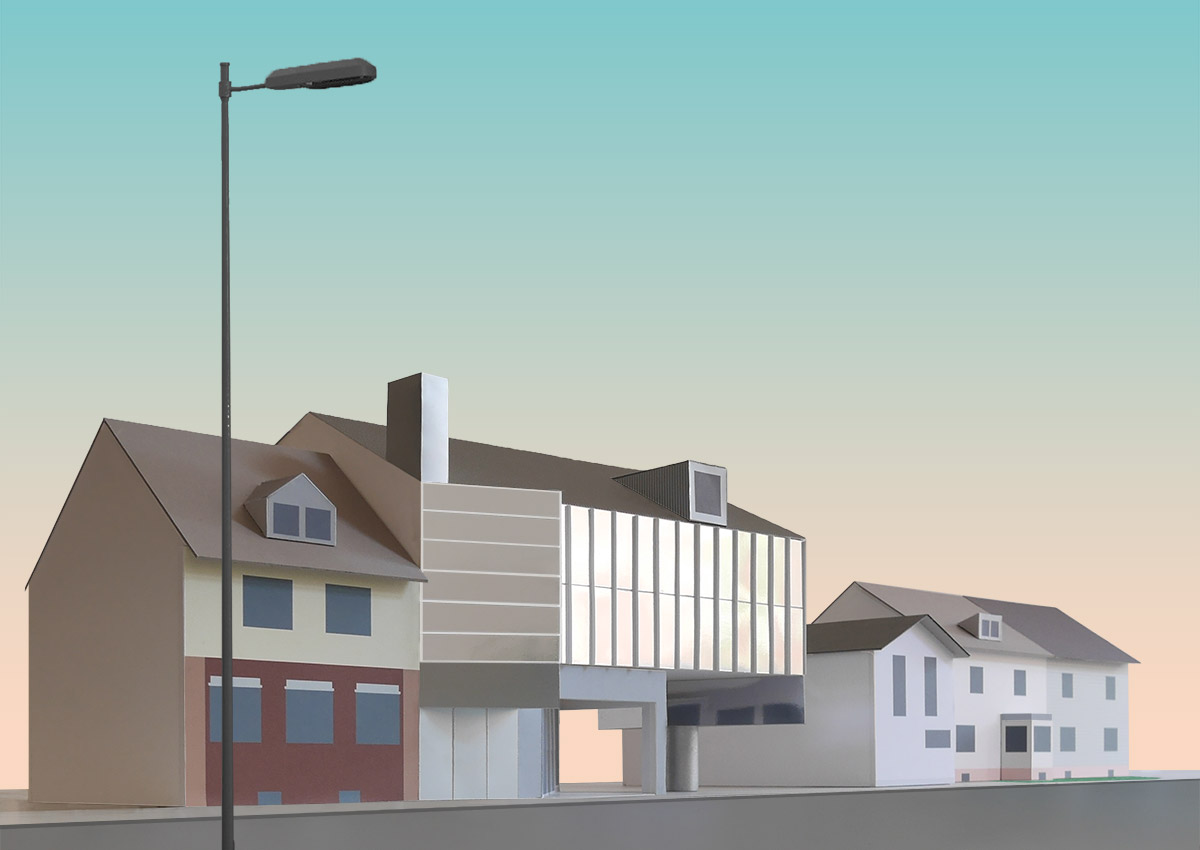

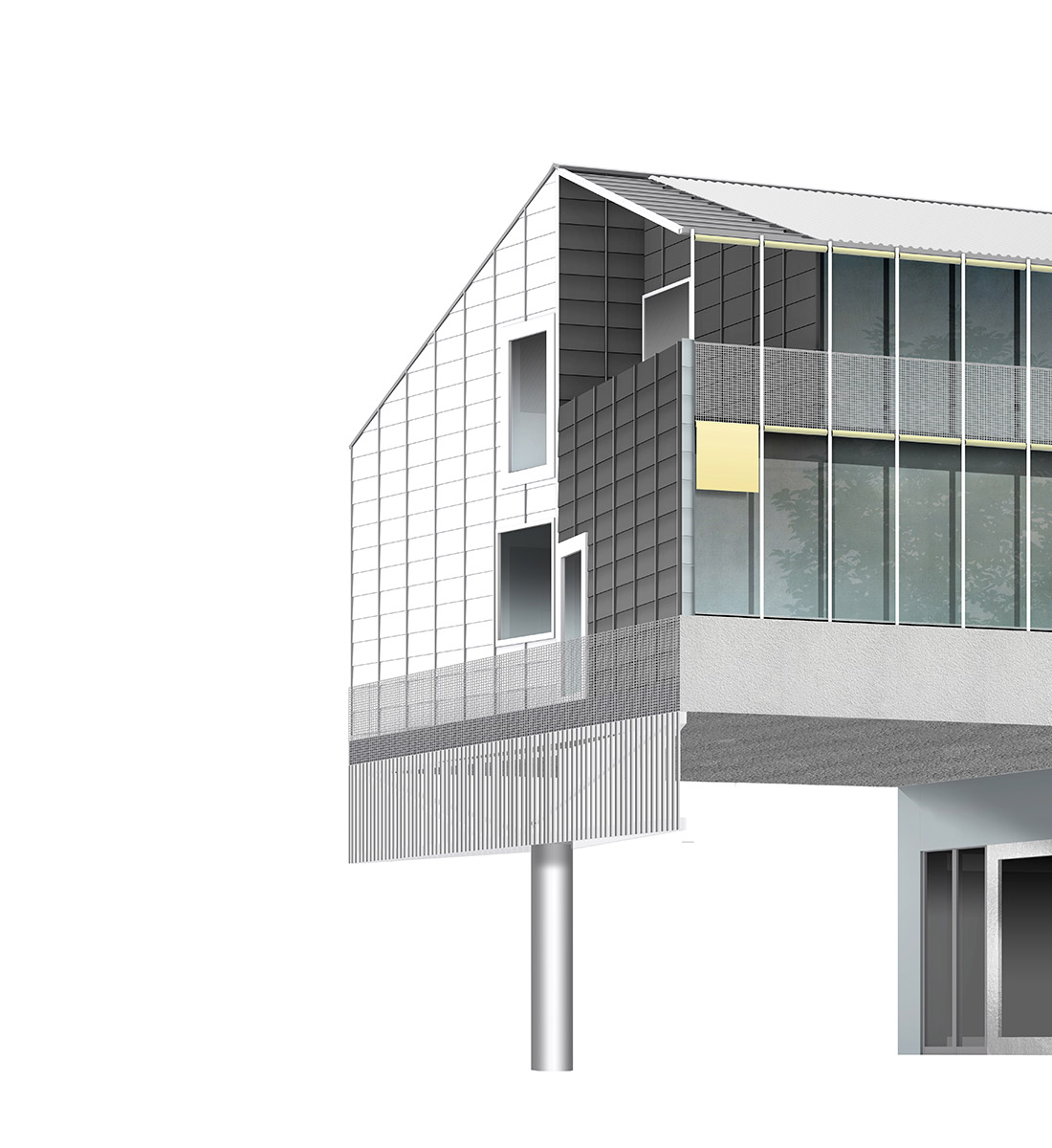

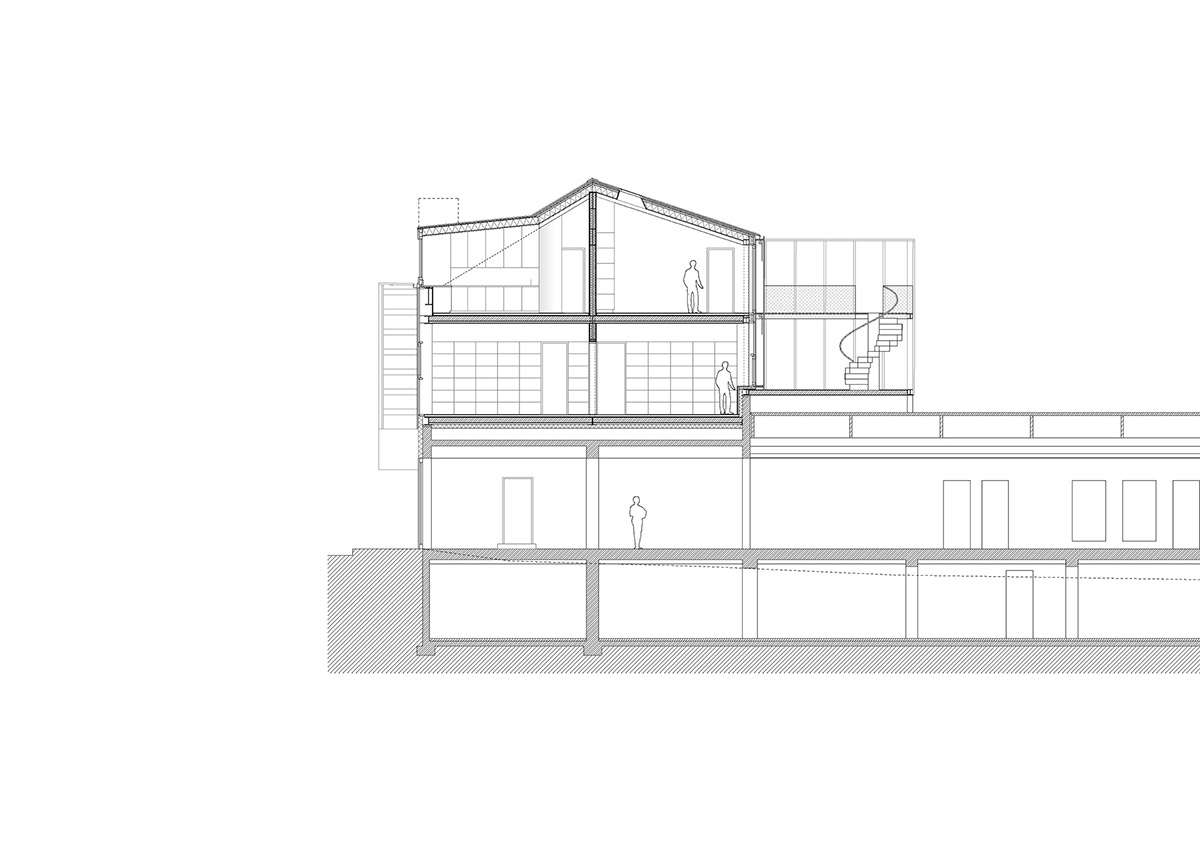

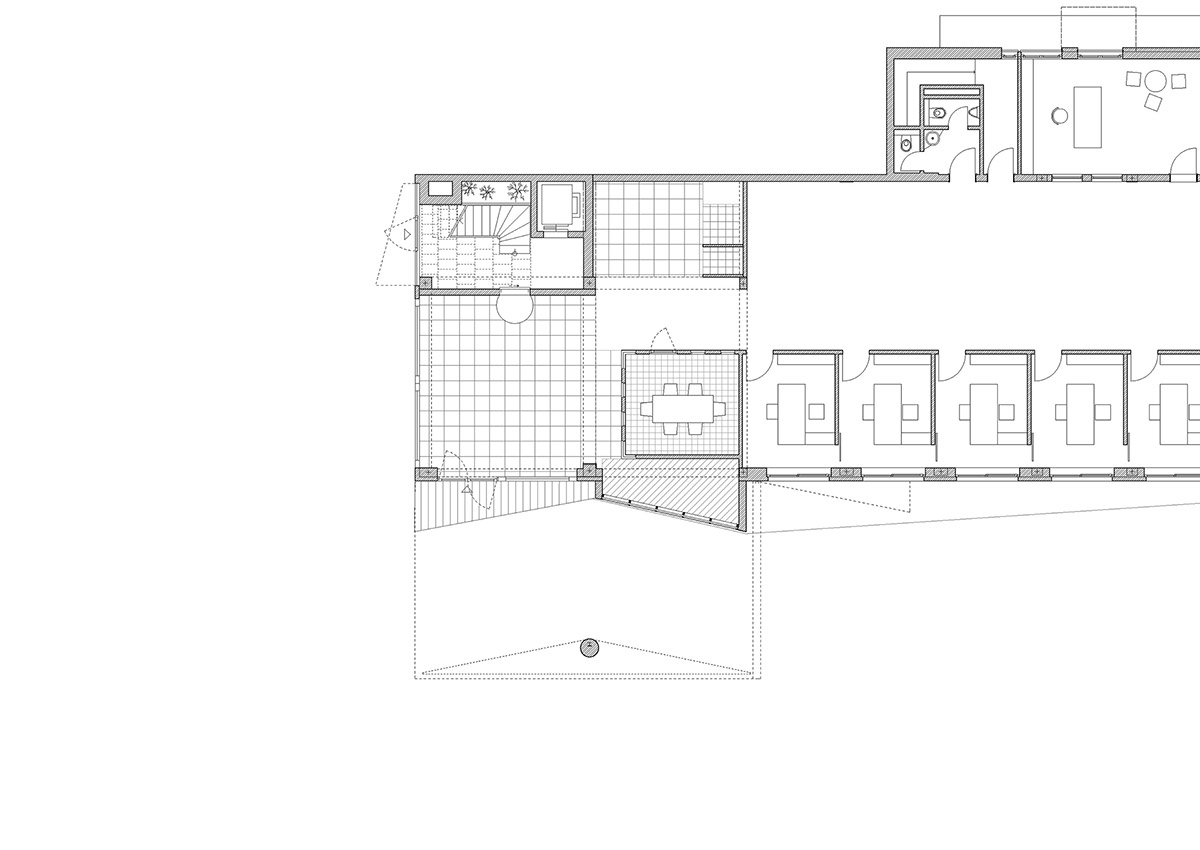

The project will close the gap within the streetscape and add to its series of houses with a new building that extends the existing Ground Floor with a gable, long facade and pitched roof volume. Instead of knocking down building fabric the entrance, Ground Floor unit and a wing-shaped space-frame column collectively form a plinth for the house above.

Its structure and grid simply builds on what is there, with a bridge house that provides offices on the first floor and two lofty flats under the roof volume, both facing south to a large deck terrace with rich green planting. A thin steel-frame superstructure only needs lightweight walls to make flexible internal layouts that can adapt to allow for different user scenarios regarding the number of offices or flats. Since all units have access to large balconies and vertical risers have been placed strategically the offices could be converted into flats and vice versa. The house will solely use renewable energies to serve as a model for the client’s company, which provides M+E services design and installation with the ambition to optimise sustainability with new technology.

Project: Transformation and extension of an existing building, with shop display, offices and housing

Period: Since 2019, ongoing for construction

Location: Troisdorf

Website: https://berndschmutz.com

Instagram: @berndschmutz / @studio_berndschmutz

Photo Credits: Bernd Schmutz

Interview: kntxtr, ah + kb, 04/2022