24/008

Lion Schreiber

Architect/Visual Artist

Berlin

«In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective.»

«In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective.»

«In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective.»

«In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective.»

«In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective.»

Please, introduce yourself and your studio…

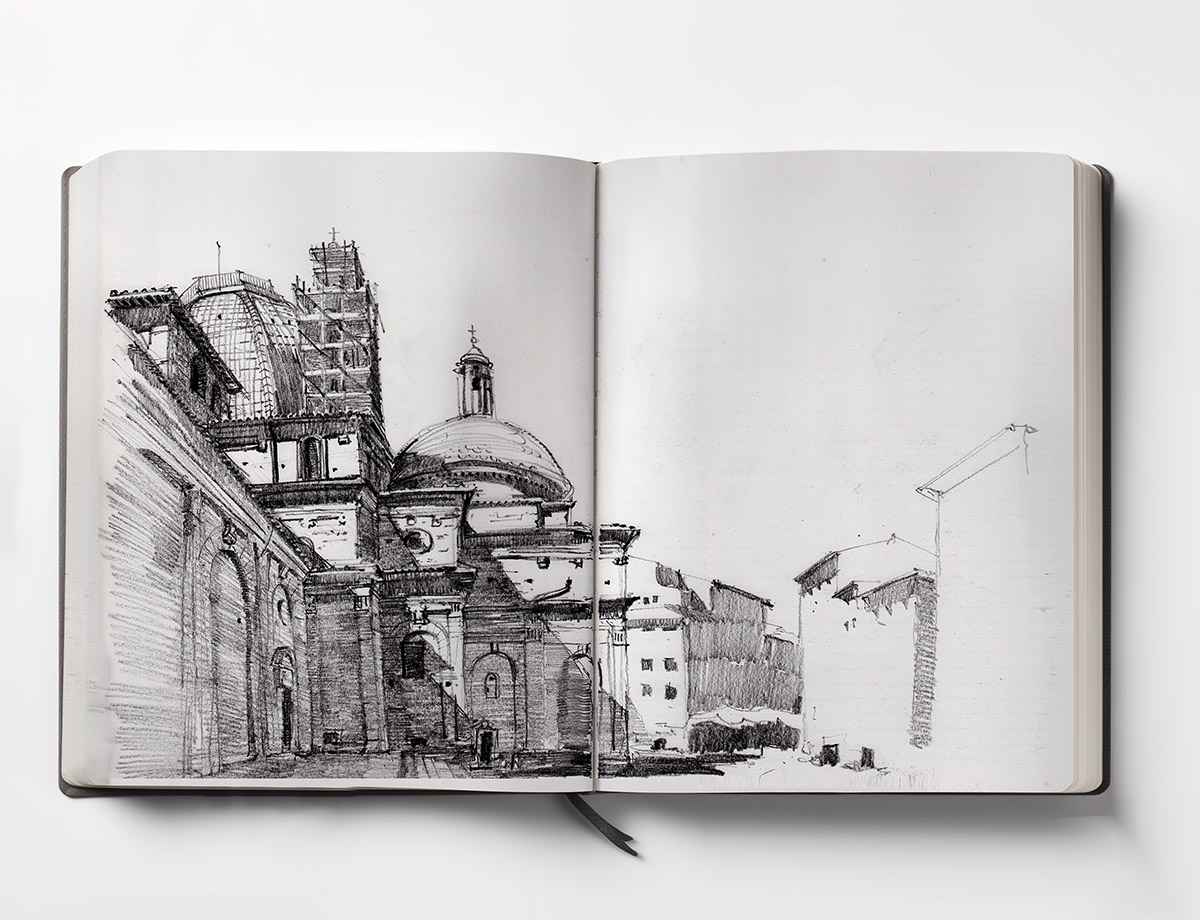

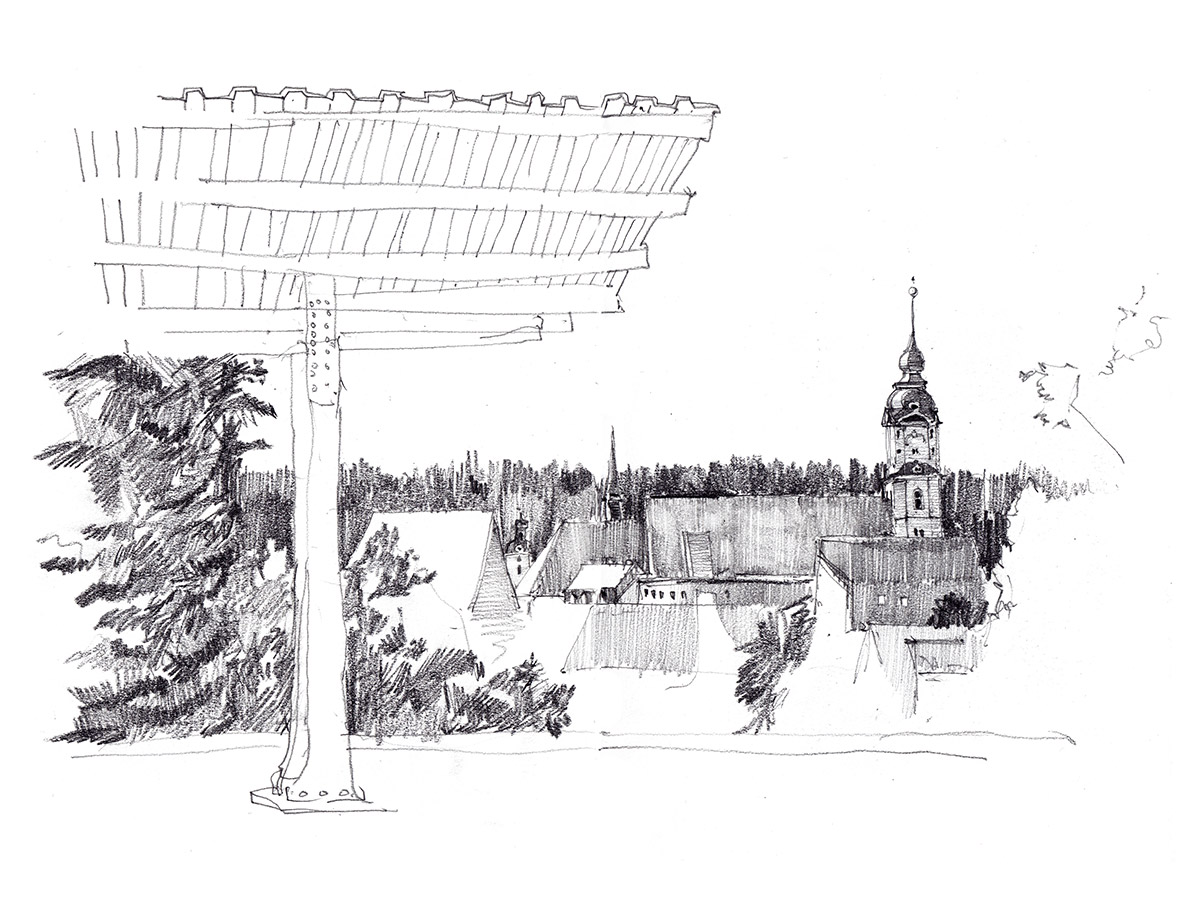

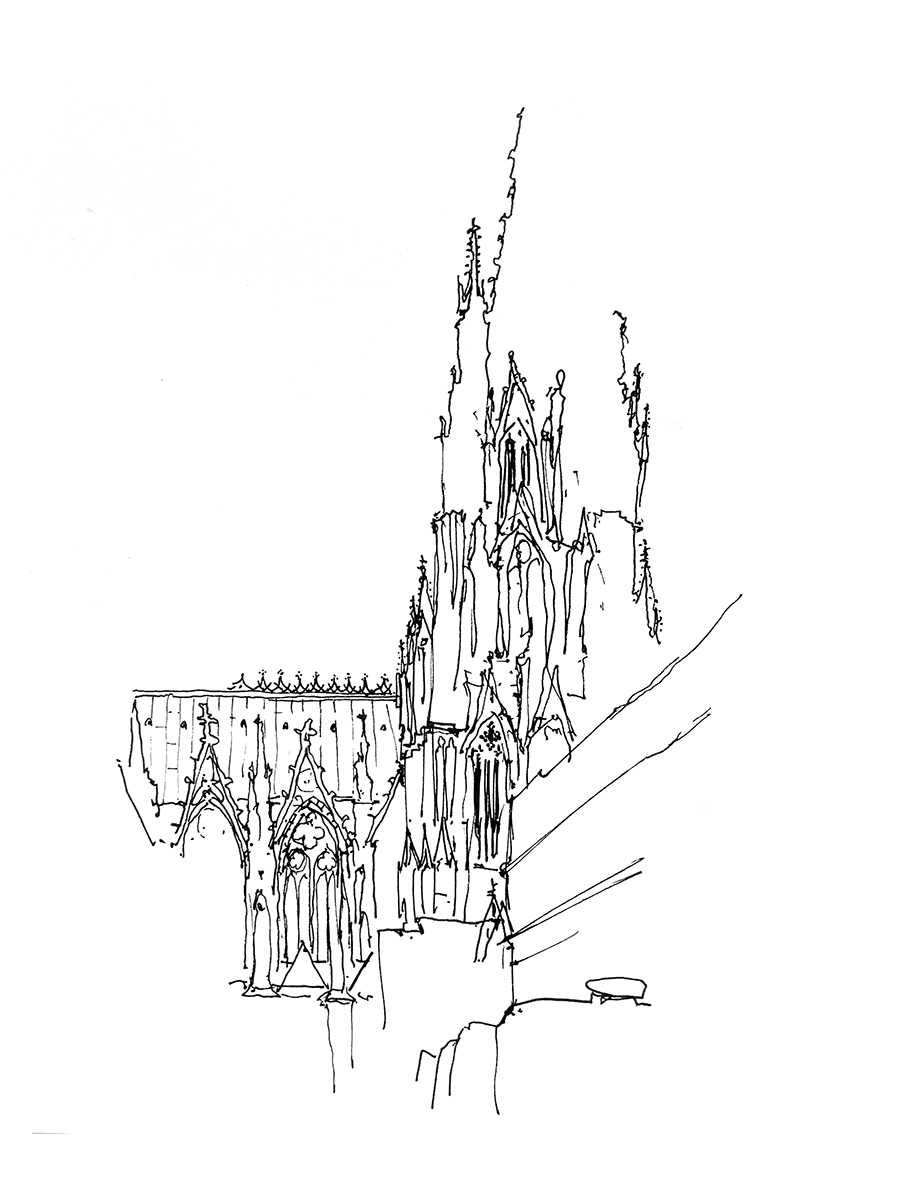

My name is Lion Schreiber, and I am an architect working at the convergence of design, imagery and drawing. My background is deeply rooted in manual drawing, sketching, and analog image creation. I create visualizations of architectural projects of other offices. Simultaneously, I actively contribute to competitions and the realization of projects within an office I co-founded with fellow architects called Gruppe 030.

Portrait Lion Schreiber – © José Gomes

How did you find your way into the field of architecture? Why are you fascinated by your work/architecture in general?

I have always enjoyed drawing and painting, but I began my studies with the vague intention to renovate old houses. Over the years and many detours later, I have ended up at a completely different point that, however, connects so many things I love, not least of which is drawing and engaging with historical structures.

What fascinates me about Architecture might come down to the three following aspects:

Firstly, it is an incredibly rewarding practice as it involves creating something tangible and visible. This doesn't necessarily require physically constructing a building; even a well-crafted plan drawing, an evocative image, or a meticulously thought-out concept is something you can admire, hold in your hands, take pleasure in, and feel proud of.

Another fascinating aspect of our work is the continuous encounter with diverse contexts when dealing with various tasks, assignments, and typologies as architects. Engaging with the history of a place or understanding the processes of the users we design for is inherently captivating. Whether it's through reading and learning or exploring different cities, locations, and sites, the work remains dynamic and intellectually enriching. Simply put, it never becomes mundane because no two tasks are ever identical.

And lastly – but this probably requires the privilege of physically constructing something – you might even contribute to making the world a slightly better place, as clichéd as it may sound. This positive impact can manifest on various levels, be it by creating highly sustainable buildings, by enhancing the aesthetic appeal of a street with a beautiful facade or providing an entirely new interpretation of a space.

What are your experiences founding your own practice?

It is, of course, an obvious statement to say that establishing an architectural firm is challenging primarily because one must first find clients who are willing to entrust the planning and construction of a house to you. In my circle of friends and acquaintances (where many young firms often find their initial projects), I have unfortunately experienced that many people either do not want or cannot afford an architect, or simply do not see the necessity for one.

The other alternative is, of course, participating in competitions. Although our Gruppe 030 has been quite successful in this regard, it remains a tough and demanding process. The conditions and prerequisites imposed before even being eligible to participate can be quite overwhelming. We live in times where it is not particularly easy for young offices to emerge. The established players with their experience and references enjoy a significant advantage in this regard. This is why we are constantly looking for collaborations and have already successfully cooperated with other offices.

The best thing that happened to me, however, is working in a group with great and talented people. Engaging in dialogue with dedicated colleagues allows for reflecting on one's decisions and achieving better results much faster. Besides, it’s way more fun.

What does your desk/working space look like?

Working Space – Lion Schreiber

What is your favorite tool to design/create architecture and why?

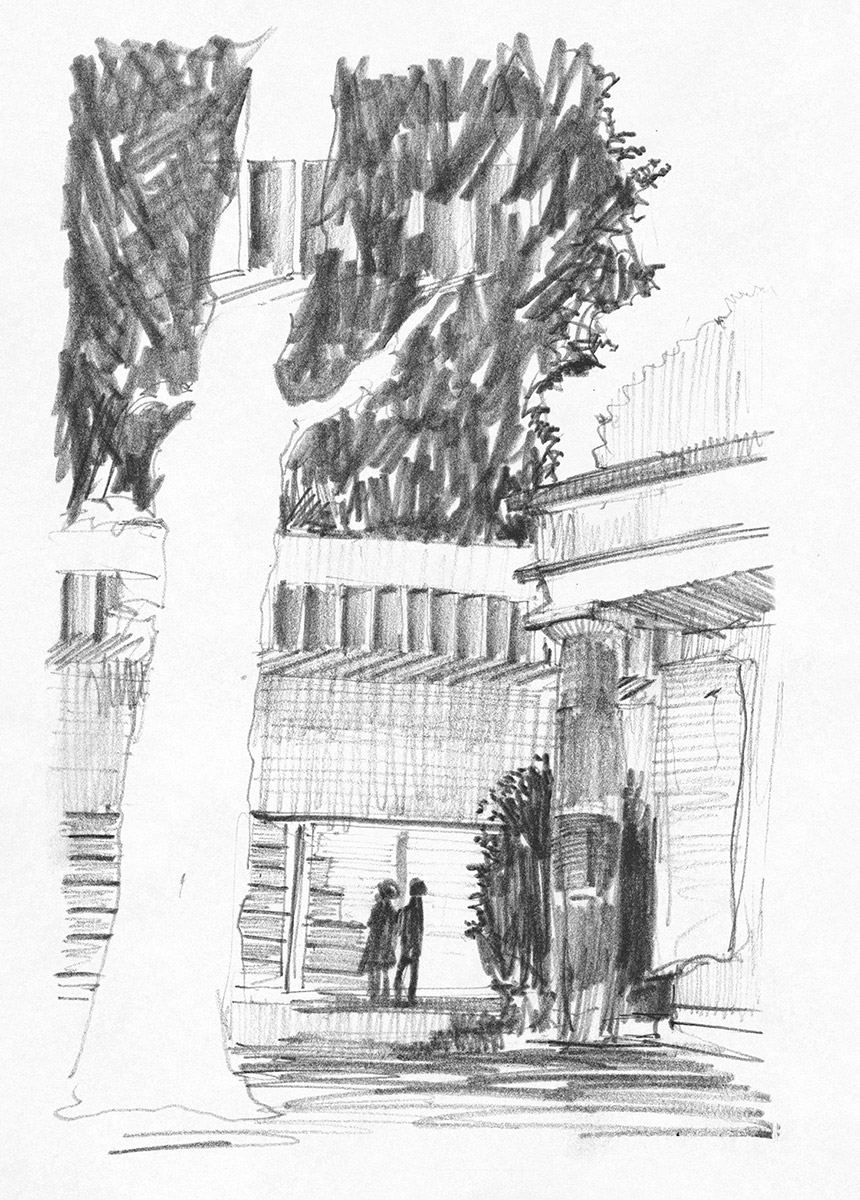

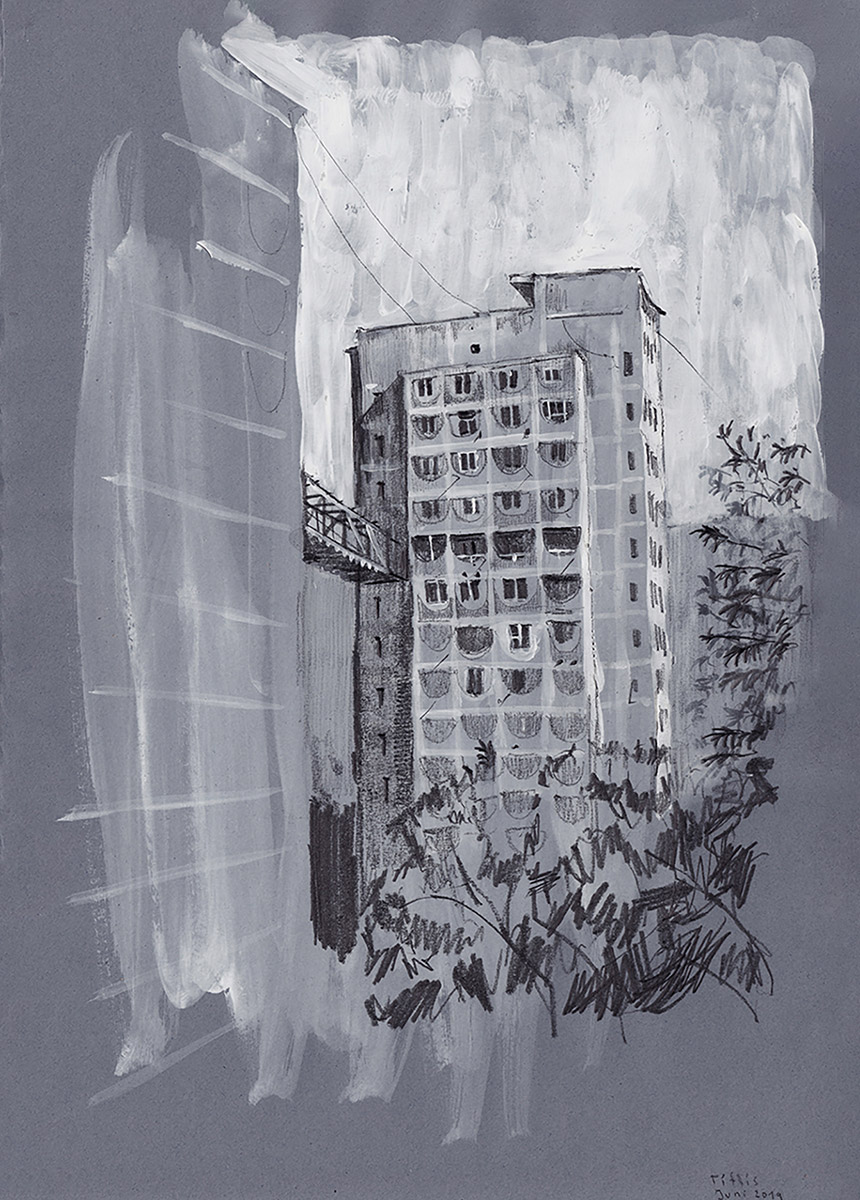

I find that working with and thinking in images is a crucial aspect of the design process. While a spatial sketch allows for the examination of a space envisioned in plan and section, I've come to realize that the projects I work on gain a different dynamic when one constructs 'desired images' that engage with spatial situations, moods, and materials.

I perceive this as an intuitive approach that can enable us to juxtapose spatial qualities with the purely quantifiable aspects of architecture, using it as a catalyst and guiding principle for phenomenological design. The choice of medium itself is not crucial at this point. The quickest is always the pen on paper, which should be readily available at all times. However, digital collages, reference projects altered in Photoshop, or, more recently, working with image-generating artificial intelligences can be very intriguing and enriching.

Therefore, I view the image itself as a tool for designing architecture.

What is the essence of architecture for you personally?

That is indeed a profound question. I have three keywords in mind that I would like to explain:

The first one is simplicity. And by that, I don't mean minimalism, but rather that things possess a clarity, are understandable, and explain themselves. This applies to both an architectural design as a whole and its individual aspects such as the simplicity of shapes or the effortlessness of an urban design composition. Paradoxically, this lightness is often the result of hard work.

The next term could be called materiality. Primarily, it's about things appearing as what they actually are, moving away from false surfaces and plastic. Additionally, every building material and component must address the new (and old) questions of sustainability in manufacturing and recyclability.

And finally, the concept of new readings: Architects should train their visionary mind. It is crucial to envision places and situations (of all scales) beyond their current state. There is this famous term 'Möglichkeitssinn' coined by the Austrian author Robert Musil, describing it as the ability to see something that does not (yet) exist but could.

The result, ideally, is an architectural intervention that completes an existing situation in a way that is surprising and simple, leaving nothing more to be changed from an architectural perspective.

What needs to change in the field of architecture according to you? How do you imagine the future?

In the general discourse on architecture, I wish for a heightened awareness of the fundamental aspects of architecture and a shift away from the quantitative, number-based perspective towards a more holistic, mature approach. This encompasses various aspects:

Firstly, an awareness of a new kind of sustainability: Moving away from purely quantifiable aspects such as the thickness of insulation. Building (and beyond) should also focus on aspects of reusability and demountability, or sometimes even the question: do I really need to demolish a house?

Sustainability exists on so many more levels: social sustainability, the endurance and resilience of spaces in terms of their usability, the universality and longevity of spatial qualities and clever solutions, both on a large and small scale.

The previously mentioned aspect of honesty of materials: Not only thinking in terms of cleaning cycles or other practical considerations but also allowing the question: what do I want to surround myself and my fellow human beings with? What surfaces do I want to touch every day? At its core, it's about acknowledging beauty and quality (which is not synonymous with expensive) as perhaps an immeasurable but essential asset in everyday life.

And last but not least, a reflective discourse on our (cultural) approach to architectural heritage. Starting with questioning reconstruction and demolition projects alike, cultivating a culture of remembrance, to grappling with concepts like authenticity and identity.

In conclusion and as a forward-looking statement, I would like to add that I believe architecture and its role in society must be conveyed differently and much more intensively already in schools. Because this form of awareness is something we need as a society, not just as individuals.

Whom would you call your mentor?

In hindsight, I can identify a couple of people who influenced me over the years. During my time at RWTH Aachen, there was Professor Thomas Schmitz (Chair for Visual Arts) who truly encouraged and supported me in pursuing my studies. I learned a lot about drawing and sketching from him, both as a manual skill and as a means of observation and representation. Under his guidance and with his team, we conducted several unforgettable drawing excursions to places nearby and far away, leaving a lasting impression on me.

I owe my perspective on the role of the image and its potential to Professor Karl-Heinz Schmitz in Weimar. And last but not least, José Gutierrez Marquez, whose way of thinking and talking about architecture, as well as designing it, has greatly influenced me to this day.

How do you communicate/present Architecture?

In the core of presenting an architectural design, the narrative, or conceptual idea, always takes precedence for me. It forms the foundation of the story and provides the justification for decisions. All levels of communication should reference it; every drawing, every image, and every spoken word should be accountable to the narrative.

Lately, I also find the medium of moving images and animations to be beneficial and intriguing. And of course the use of the image itself as one of the most powerful conveyors of ideas, emotions and atmospheres.

Creating Images to visualize the ideas of architects and designers seems to be a delicate thing. How important is the relationship and communication between you and your clients?

It is definitely helpful to have some sort of common ground with the client, because if not, it can be very time consuming and lead to bad results. But usually this common ground is already established by the fact that a client commissions me because he likes the style and the kind of images I make and knows what he can expect.

In my communication, I try to differentiate between the different aspects an image can be judged by. For example: often, the expectations for an image are that it should explain everything at once. At the same time, one could, aim for an image that captivates through its strong graphic and visual quality (the keyword here is composition). These things do not necessarily exclude each other, but we oftentimes find ourselves in a discussion about this kind of pros and cons with the client, a process that generates a heightened awareness for all levels of the project and the way it is communicated. This process is very valuable and enriching for the end result.

Do you think AI will change the way architectural imagery is produced?

With no doubt artificial intelligence will change the entire world of image production in all branches and profession, including architectural visualization. I found this quite depressing at first because I was afraid this will put me and everyone else out of business. But over time, and engaging with some AIs, I think being able to use them can be very advantageous and will require a new set of skills.

AI should be considered first and foremost a tool that is supposed to help us. We should still be able to perform certain tasks on our own, we need to cultivate and learn all the architectural core skills. You should preserve the ability to carry out certain tasks yourself or, at the very least, be able to understand them. You should never find yourself limited by a new technology or giving away actual control.

Currently, AI helps me in all kinds of small steps in my workflow. For example, when I look for 2D assets, I rely less and less on the established libraries, but let text-to-image-AI generate people, trees and objects to populate and detail my images with. It’s just faster and more effective.

I have also experimented with using AI during design process, though it was more on a brainstorming or moodboard kind of level. For example when merging your own reference images with a text prompt in order to alienate it for your own context, there can be inspiring or surprising results that might to a certain degree give you input for the further process.

But here is the reason why I think none of the AIs I am aware of today will replace neither architect nor image-maker anytime soon: making sense of it all. While many sub-tasks, often the tedious ones, can be taken over by machines, keeping the broader picture in mind will remain within the domain of the human mind. I'm referring to the art of devising a piece of architecture with meaning in its urban, historic, and social context, and crafting a coherent narrative that explains and conveys the idea. Or, in the case of image making: Telling a story through images in their layout and composition.

To put it polemically, the tasks and skills that will remain with us (for now) are gathering information, sorting and judging it, making active decisions and placing them in a context.

What does it take to create a good architectural image?

For me, the core ingredient of a good image is a powerful composition. What I mean is the dynamic and orientation of shapes on the canvas. In addition, you have to be very clear about what the message of the image is supposed to be. When comparing the different options for viewpoints I usually give each suitable image a title in order to elicit or to define the core message the respective image is supposed to convey.

If these two things – strong composition and clear message – are established, that’s half the battle in my opinion. From then on, it is all about not making things worse, thoroughly working on the details and not losing the big picture out of sight.

If there were one skill you could recommend to a young architect to study in depth at architecture school: what would it be and why?

I would advocate for the skill of manual drawing and sketching. It is so fundamental and holds such diverse benefits that I can't think of any reason why one should skip learning it.

It allows a person to engage with the surroundings in diverse ways: Firstly, drawing on site serves as a tool for observation. It hones perception and enables one to translate spaces, proportions, and realities onto a two-dimensional surface. This process develops a sense for perspective, composition, and the situational – in the selection of the subject and the construction of the image. Simultaneously, drawing allows us to recognize, experience, and process places in a very intense, physical manner.

Conversely, drawing is the most immediate means of communication for an architect during the design process. It serves as the direct channel from the mind to the paper, both in dialogue with others and in the monologue with oneself. Should this ability diminish or remain uncultivated, you deprive yourself of a means of communication – perhaps the most immediate one.

What person/collective or project do we need to look into right now? Recommend any office/architect/artist that you find inspiring:

Bernard Rudofsky – his theoretical work

Per Adolfsen – inspiring drawings

Noah Yuval Harari – puts things in perspective

Aleida Assmann – about collective memories

Project